Vittorio Garatti

.jpg)

Vittorio Garatti (born 1927 in Italy) is an Italian architect.

Biography

.jpg)

.jpg)

He graduated in architecture in 1957 from the Politecnico di Milano, where Ernesto Nathan Rogers was a major influence. Guido Canella and Gae Aulenti were his classmates.

The Venezuelan experience

In that same year, Garatti departed for Venezuela, where he found employment in the Banco Obrero project led by architect Carlos Raúl Villanueva, and began teaching at the University in Caracas. Garatti, like fellow architect and Banco Obrero project mate Roberto Gottardi, had been a young participant in the post-war debate in Italy against Rationalism, a critique that was led by such figures as Ernesto Nathan Rogers, Carlo Scarpa, Mario Ridolfi, Giuseppe Samonà and Bruno Zevi.

The Cuban experience

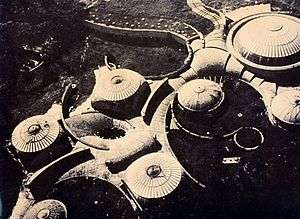

Following the victory of the Cuban Revolution, Cuban-born architect (and Banco Obrero participant) Ricardo Porro invited Garatti and Roberto Gottardi to join him in Havana in early 1961. Garatti soon began work with Porro and Gottardi on the ambitious project of Havana's new National Art Schools, commissioned by Fidel Castro and Che Guevara, in the context of the educational policy promoted immediately after the revolution. The architectural complex was to be built in the most exclusive upper-class Cuban district,[1] the Country Club. The intention was to create a cultural center of extraordinary dimension, opened to the developing countries of three continents, just 90 miles from the symbol of American imperialism.

The School of Music and the School of Ballet

Garatti designed the School of Music and the School of Ballet[2] as a complex of bricks, pottery, and Catalan vaulted structure that reflected the optimism and exuberance of the time. The schools wanted to reinvent the architecture, as the revolution was hoping to reinvent society.

Vittorio Garatti writes: "We took care to invade as little as possible the golf. We located several schools on the outskirts of the park, closer to the upper-middle class houses arranged along that sort of ring that surrounds the golf course and that were designed as a accommodation for the students. At the center of the park existed the building of the club, with a large restaurant and a swimming pool, which was destined to common services (canteen, meeting, etc.)."

The construction of the complex was interrupted after the missile crisis, when the naval blockade imposed by the United States forced to a different assessment for economic and productive priorities.

The School of Arts' good consideration underwent on an ideological disgrace as a consequence of a different political and cultural mindset that considered the utopian architecture politically incorrect when compared to the Soviet building style that was acquiring dominance in the island.[1][3] In 1965 the whole complex was abandoned,[1] fell into ruins, and part of the materials were removed to be reused in other construction.

Other construction in Cuba

In 1962 he realized the Escuela Andre Voisin in Guines, while in 1966-67, with Sergio Baroni and Hugo d'Acosta, he designed the Cuban pavilion at the Expo 1967 in Montreal. Over the years 1968/70, with Max Vaquero, Eusebio Azcue, and urban planner Jean-Pierre Garnier, he supervised the development plan of the capital.

Back to Italy

As a result of a changed cultural climate and ideological, Vittorio Garatti ended up being viewed with suspicion and went under arrest for twenty days, in June 1974 on charges of spying. In that same year he was forced to leave the country by force. He believes that his expulsion was the result of a conspiracy with the CIA that was trying to expel the foreign professionals who collaborated with the Cuban regime.

Garatti moved in Italy, where he practises as an architect.

Restoration projects for the Escuelas Nacional de Arte

The case of the unfinished project of the Escuelas began to emerge in 1999 with the publication, of the first edition of the book Revolution of Forms - Cuba's Forgotten Art Schools by John A. Loomis, architect and professor at the City College of New York. On 28 February 2003 the site was included on the Tentative List of World Heritage Sites by UNESCO, in the category of cultural heritage.

These events gained to the abandoned architectural complex a renewed interest: Loomis' book inspired the video-documentary Unfinished Spaces, produced and directed by Alysa Nahmias and Benjamin Murray. Fundraising initiatives have been proposed to help with the restoration and the preservation of the project.

In November 2012 international press announced a project of restoration and re-use of the Havana Escuelas Nacional de Arte complex put forward by Cuban ballet superstar Carlos Acosta. According to the BBC, Acosta planned "to create a new model of [ballet] school... that would be financially self-sustaining, run as a non-profit-making charity". According to the article, however, the project was stalled because of the opposition of Vittorio Garatti, who "is protesting that he has been sidelined. He has written to Cuba's Communist leaders claiming that Acosta wants to 'appropriate' and 'privatase' his building" (S. Rainsford, "Carlos Acosta's Cuban ballet school dream", BBC News, 18 November 2012).

The Vittorio Garatti's Committee

The “Vittorio Garatti”’s Committee is a non-profit organization that aims to raise the funds for the renovation, the preservation and the finalization of three of the five schools that constitute the NATIONAL SCHOOLS OF ARTS of Cubanacan, La Habana (Cuba) and in the detail they are:

- The School of Ballet - designed by arch. Vittorio Garatti.

- The School of Music - designed by arch. Vittorio Garatti.

- The School of Dramatic Arts - designed by arch. Roberto Gottardi.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Orsi, Peter (2012). "Plan for Cuban landmark's rebirth sparks debate". New York Daily News. New York, United States. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- ↑ Revolution Of Forms website, architect profiles page. Retrieved 02-22-11

- ↑ Revolution Of Forms website, ibid. Retrieved 02-22-11

Bibliography

- Loomis, John A., Revolution of Forms - Cuba's Forgotten Art Schools (Princeton Architectural Press, New York, 1999 & 2011, ISBN 978-1-56898-988-4)

- María Elena Martín and Eduardo Luis Rodríguez: Havana, Cuba: An Architectural Guide (Junta de Andalucía, Sevilla, 1998, ISBN 84-8095-143-5)

- Eduardo Luis Rodríguez: The Havana Guide, Modern Architecture, 1925-1965 (Princeton Architectural Press, New York, 2000, ISBN 1-56898-210-0)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Vittorio Garatti. |

- Revolution of Forms website, a book about the Cuban National Art Schools