William Whitelaw, 1st Viscount Whitelaw

| The Right Honourable The Viscount Whitelaw KT CH MC PC DL | |

|---|---|

| |

| Leader of the House of Lords Lord President of the Council | |

|

In office 11 June 1983 – 10 January 1988 | |

| Prime Minister | Margaret Thatcher |

| Preceded by | Baroness Young |

| Succeeded by | Lord Belstead |

| Home Secretary | |

|

In office 4 May 1979 – 11 June 1983 | |

| Prime Minister | Margaret Thatcher |

| Preceded by | Merlyn Rees |

| Succeeded by | Leon Brittan |

| Shadow Home Secretary | |

|

In office 11 April 1976 – 4 May 1979 | |

| Leader | Margaret Thatcher |

| Preceded by | Ian Gilmour |

| Succeeded by | Merlyn Rees |

| Deputy Leader of the Conservative Party | |

|

In office 11 February 1975 – 7 August 1991 Serving with Sir Geoffrey Howe (1989–1990) | |

| Leader |

Margaret Thatcher John Major |

| Preceded by | Reginald Maudling[a] |

| Succeeded by | Michael Heseltine (1995)[b] |

| Chairman of the Conservative Party | |

|

In office 4 March 1974 – 11 February 1975 | |

| Leader | Edward Heath |

| Preceded by | Peter Carington |

| Succeeded by | Peter Thorneycroft |

| Secretary of State for Employment | |

|

In office 2 December 1973 – 4 March 1974 | |

| Prime Minister | Edward Heath |

| Preceded by | Maurice Macmillan |

| Succeeded by | Michael Foot |

| Secretary of State for Northern Ireland | |

|

In office 24 March 1972 – 2 December 1973 | |

| Prime Minister | Edward Heath |

| Preceded by | Office created |

| Succeeded by | Francis Pym |

| Leader of the House of Commons Lord President of the Council | |

|

In office 20 June 1970 – 7 April 1972 | |

| Prime Minister | Edward Heath |

| Preceded by | Fred Peart |

| Succeeded by | Robert Carr |

| Chief Whip of the Conservative Party | |

|

In office 16 October 1964 – 20 June 1970 | |

| Leader |

Sir Alec Douglas-Home Edward Heath |

| Preceded by | Martin Redmayne |

| Succeeded by | Francis Pym |

| Member of Parliament for Penrith and The Border | |

|

In office 26 May 1955 – 11 June 1983 | |

| Preceded by | Donald Scott |

| Succeeded by | David Maclean |

| Member of the House of Lords Lord Temporal | |

|

In office 11 June 1983 – 1 July 1999 Hereditary Peerage | |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

William Stephen Ian Whitelaw 28 June 1918 Nairn, Scotland |

| Died |

1 July 1999 (aged 81) Penrith, England |

| Political party | Conservative |

| Alma mater | Trinity College, Cambridge |

| a. ^ Office vacant from 18 July 1972 to 11 February 1975. b. ^ Office vacant from 1 November 1990 to 5 July 1995. | |

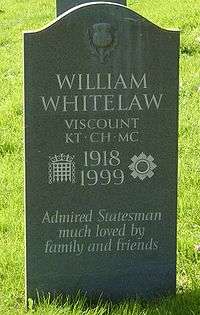

William Stephen Ian Whitelaw, 1st Viscount Whitelaw, KT, CH, MC, PC, DL (28 June 1918 – 1 July 1999), often known as Willie Whitelaw, was a British Conservative Party politician who served in a wide number of Cabinet positions, most notably as Home Secretary and de facto Deputy Prime Minister.[1][2][3] He was Deputy Leader of the Conservative Party from 1975 to 1991.[4]

Early life

Whitelaw was born at the family house "Monklands" on Thurlow road, Nairn, in northeast Scotland. He never knew his father, William Alexander Whitelaw (born 1892), a member of a Scottish landed gentry family,[5][6] who was killed in the First World War when he was a baby. Whitelaw was raised by his mother, a local councillor in Nairn, and paternal grandfather, William Whitelaw (1868–1946), of Gartshore, Dunbartonshire, an Old Harrovian and alumnus of Trinity College, Cambridge,[7] landowner, MP for Perth 1892–1895, and chairman of the London and North-Eastern Railway Company.[8] His great-aunt, by marriage, Dorothy, was the niece of former Prime Minister and author Benjamin Disraeli.[6][5]

Whitelaw was educated first at Wixenford School, Wokingham, before passing the entrance exam to Winchester College. From there he went up to Trinity College, Cambridge, where he won a blue for golf and joined the Officer Training Corps. By chance he was in a summer camp in 1939 on the outbreak of the Second World War and was granted a regular, not wartime, commission in the British Army, in the Scots Guards, later serving in the 6th Guards Tank Brigade, a separate unit from the Guards Armoured Division. He commanded Churchill tanks in Normandy during the Second World War and during Operation Bluecoat in late July 1944. His was the first Allied unit to encounter German Jagdpanther tank destroyers, being attacked by three out of the twelve Jagdpanthers which were in Normandy.[9]

The battalion's second-in-command was killed when his tank was hit in front of Whitelaw's eyes, and Whitelaw succeeded to this position, holding it, with the rank of Major, throughout the advance through the Netherlands into Germany and until the end of the war. He was awarded the Military Cross for his actions at Caumont; a photograph of Field-Marshal Bernard Montgomery pinning the medal to his chest appears in his memoirs. After the end of the war in Europe, Whitelaw's unit was to have taken part in the invasion of Japan, but the Pacific War ended before this. Instead he was posted to Palestine, before leaving the army in 1946 to take care of the family estates of Gartshore and Woodhall in Lanarkshire, which he inherited on the death of his grandfather.

Political career

After early defeats as a candidate for the constituency of East Dunbartonshire, he became Member of Parliament (MP) for Penrith and the Border at the 1955 general election, and represented that constituency for 28 years.[10] He held his first government posts under Harold Macmillan as a Lord of the Treasury (government whip) between 1961 and 1962 and under Macmillan and then Sir Alec Douglas-Home as Parliamentary Secretary to the Ministry of Labour between 1962 and 1964. In 1964 Douglas-Home appointed him as Opposition Chief Whip. He was sworn of the Privy Council in January 1967.[11]

Heath Government, 1970–1974

When the Conservatives returned to power in 1970 under Edward Heath, Whitelaw was made Lord President of the Council and Leader of the House of Commons, with a seat in the cabinet.[12] He became the first Secretary of State for Northern Ireland after the imposition of direct rule in March 1972 and he served in that capacity until November 1973. During his time, in Northern Ireland he introduced Special Category Status for paramilitary prisoners. He attempted to negotiate with the Provisional Irish Republican Army with the then PIRA Chief of Staff Seán MacStiofáin in July 1972. The talks ended in an agreement to change from a seven-day truce, to an open-ended truce, which did not last long. As a briefing for prime minister Edward Heath later noted, Whitelaw "found the experience of meeting and talking to Mr MacStíofáin very unpleasant". MacStiofáin in his memoir, complimented Whitelaw, saying he was the only Englishman ever to pronounce his name in Irish correctly.[13]

He left Northern Ireland in 1973 to become Secretary of State for Employment shortly before the Sunningdale Agreement was reached, to confront the National Union of Mineworkers over pay demands. The dispute was followed by the Conservative party losing the February 1974 general election. Also in 1974, Whitelaw became a Companion of Honour.[14]

In opposition, 1974–1979

Soon after Harold Wilson's Labour Party returned to government, Heath appointed Whitelaw as Deputy Leader of the Opposition and Chairman of the Conservative Party. After a second defeat in the October 1974 general election – during which Whitelaw had accused Harold Wilson of going "round and round the country stirring up apathy", Heath was forced to call a leadership election in 1975. Whitelaw loyally refused to run against Heath; however, and to widespread surprise, Margaret Thatcher narrowly defeated Heath in the first round. Whitelaw stood in his place and lost convincingly, against Thatcher in the second round. The vote polarised along right-left lines, with in addition the region, experience and education of the MP having their effects.[15]

Whitelaw managed to maintain his position as Deputy Leader until the 1979 general election, when he was appointed Home Secretary. He was widely considered to be the de facto Deputy Prime Minister in Thatcher's new government.[2][3][16]

Home Secretary, 1979–1983

Thatcher was a firm fan of Whitelaw's, and appointed him Home Secretary in her first Cabinet, later writing of him "Willie is a big man in character as well as physically. He wanted the success of the Government which from the first he accepted would be guided by my general philosophy. Once he had pledged his loyalty, he never withdrew it".[17]

As Home Secretary, Whitelaw adopted a hard-line approach to law and order. He improved police pay and embarked upon a programme of extensive prison building. His four-year tenure in office, however, was generally perceived as a troubled one. His much vaunted "short, sharp shock" policy, whereby convicted young offenders were detained in secure units and subjected to quasi-military discipline won approval from the public but proved expensive to implement and largely ineffectual in stemming burgeoning crime rates. He was the British Home Secretary during the 6-day long Iranian Embassy siege in London, 30 April 1980 – 5 May 1980.

In March 1981, he approved Wolverhampton council's 14-day ban on political marches in the borough in response to a planned National Front demonstration there.[18]

Inner city decay, unemployment and what was perceived at the time as heavy-handed policing of ethnic minorities (notably the application of what some called the "notorious" sus law) sparked major riots in London, Liverpool, Bristol and a spate of disturbances elsewhere. The Provisional IRA escalated its bombing campaign on England.

Leader of the House of Lords, 1983–1988

Two days after the 1983 general election, Whitelaw received a hereditary peerage (the first created for 18 years) as Viscount Whitelaw, of Penrith in the County of Cumbria.[19] Thatcher appointed him Lord President of the Council and Leader of the House of Lords. Lord Whitelaw faced many challenges in attempting to manage the House of Lords, facing a major defeat over abolition of the Greater London Council within a year of taking over. However, his patrician and moderate style appealed to Conservative peers and his tenure is considered a success.

During his period as Margaret Thatcher's deputy and Leader of the Lords, Thatcher relied on Whitelaw heavily, famously announcing that "every Prime Minister needs a Willie".[20] He chaired the "star chamber" committee that settled the annual disputes between the limited resources made available by Treasury and the spending demands of other government departments. It was Whitelaw who managed to dissuade Thatcher in November 1980 from going to Leeds to take charge of the Yorkshire Ripper investigation personally.

Resignation

After a stroke in December 1987, he was forced to resign. Some people, Nicholas Ridley, among them, argued that Whitelaw's retirement marked the beginning of the end of the Thatcher premiership, as he was no longer around as often to give sensible advice and to moderate her stance on issues, or to maintain a consensus of support in her own Cabinet and Parliamentary Party.

Retirement and death

During his retirement and up until his death Lord Whitelaw was the chairman of the board of Governors at St Bees School, Cumbria. He was appointed a Knight of the Thistle in 1990.[21] He formally resigned as Deputy Leader of the Conservative Party in 1991;[4] a farewell dinner was held on 7 August 1991.[22]

He died of natural causes, aged 81, in 1999, survived by his wife of 56 years, Celia, Viscountess Whitelaw (1 January 1917 – 5 December 2011), a World War II ATS, volunteer, philanthropist/charity worker and horticulturist. The couple had four daughters. Although Whitelaw was given a hereditary peerage, the title became extinct on his death as his daughters were unable to inherit. His home for many years was the mansion of Ennim just outside the village of Great Blencow near Penrith, Cumbria. He was buried at St. Andrew's Parish Church, Dacre, Cumbria.

Styles of address

- 1918–1944: Mr William Whitelaw

- 1944–1952: Mr William Whitelaw MC

- 1952–1955: Mr William Whitelaw MC DL

- 1955–1967: Mr William Whitelaw MC DL MP

- 1967–1974: The Right Honourable William Whitelaw MC DL MP

- 1974–1983: The Right Honourable William Whitelaw CH MC DL MP

- 1983–1990: The Right Honourable The Viscount Whitelaw CH MC DL

- 1990–1999: The Right Honourable The Viscount Whitelaw KT CH MC DL

In popular culture

- Whitelaw was portrayed by John Standing in the BBC production of The Falklands Play (2002) by Ian Curteis.

- The character of Whitelaw also appeared in a smaller role in Margaret, where he was portrayed as a moderating influence on Thatcher and Michael Heseltine in Cabinet. Whitelaw was played by Robert Hardy.

- Part of a speech detailing the "Short, sharp shock" concept of juvenile offender incarceration given by Whitelaw during 1979 is excerpted in the fadeout at the end of Gerry Rafferty's song "The Garden of England" (1980), from the album Snakes and Ladders:

| “ | We Conservatives have always maintained the need for an experiment with a tougher regime for depriving young football hooligans of their leisure time. I can announce today that the experiment promised in our election manifesto is to begin in Surrey ... These will be no holiday camps. We will introduce on a regular basis drill, parades, and inspections ... from 6:45am 'til lights out at 9:30pm. Life will be conducted at a brisk tempo. | ” |

- The folk album, England's Vietnam – Irish Songs of Resistance, by the Men of No Property (Folkways Records, 1977), contains a track called "Tuten Carson's Tomb". The song portrays a tour guide supposedly guiding visitors through the St Anne's Cathedral tomb of Ulster Unionist leader Sir Edward Carson and pointing out artifacts. Referring to Whitelaw's period as the first Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, it contains the line, "A flak vest made of solid jade/A gift that Whitelaw made."

References

- ↑ "Letter to Lord Whitelaw (resignation)". Margaret Thatcher Foundation. 10 January 1988. Retrieved 21 June 2017.

- 1 2 Hennessy, Peter (2001). "A Tigress Surrounded by Hamsters: Margaret Thatcher, 1979–90". The Prime Minister: The Office and Its Holders since 1945. Penguin Group. ISBN 978-0-14-028393-8.

- 1 2 Aitken, Ian (2 July 1999). "Viscount Whitelaw of Penrith". The Guardian. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- 1 2 "Willie Whitelaw dies aged 81". The Guardian. Press Association. 1 July 1991. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- 1 2 A Genealogical and Heraldic Dictionary of the Landed Gentry of Great Britain and Ireland, 1898, volume 2, ed. Bernard Burke, pg 1585, 'Whitelaw of Gartshore'

- 1 2 http://archiveshub.ac.uk/data/gb1015-gd101

- ↑ The Railway Gazette, volume 37, 1922, pg 553

- ↑ Current Biography Yearbook 1975, H. W. Wilson & Co., 1976, pg 438

- ↑ Daglish, I. (2009). Operation Bluecoat. Pen & Sword. pp. 70–73. ISBN 0-85052-912-3.

- ↑ leighrayment.com House of Commons: Paddington to Platting

- ↑ "No. 44210". The London Gazette. 30 December 1966. p. 1.

- ↑ "No. 45134". The London Gazette. 23 June 1970. p. 6953.

- ↑ MacStiofáin, Seán Revolutionary in Ireland, pp. 281–89

- ↑ leighrayment.com Companions of Honour

- ↑ Philip Cowley and Matthew Bailey, "Peasants' Uprising or Religious War? Re-Examining the 1975 Conservative Leadership Contest," British Journal of Political Science (2000) 30#4 pp. 599–629 in JSTOR

- ↑ Charles Moore, Margaret Thatcher: From Grantham to the Falklands (2013) p 427

- ↑ Margaret Thatcher, The Downing Street Years (HarperCollins, 1993), p. 27.

- ↑

- ↑ "No. 49394". The London Gazette. 21 June 1983. p. 8199.

- ↑

- ↑ "No. 52351". The London Gazette. 30 November 1990. p. 18550.

- ↑ Sherrin, Ned (25 September 2008). Oxford Dictionary of Humorous Quotations. OUP Oxford. p. 268. ISBN 978-0-19-923716-6.

Further reading

- Moore, Charles. Margaret Thatcher: From Grantham to the Falklands (2013)

- Whitelaw, William. The Whitelaw Memoirs (1989), a primary source

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: William Whitelaw, 1st Viscount Whitelaw |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to William Whitelaw, 1st Viscount Whitelaw. |

- Burke's Peerage

- Guardian Unlimited Books (review) – The killing suit

- Obituary in The Guardian, 2 July 1999

- William Whitelaw, "The Whitelaw Memoirs", Aurum Press, London, 1989.

- Hansard 1803–2005: contributions in Parliament by William Whitelaw

.svg.png)