Autonomic nervous system

| Autonomic nervous system | |

|---|---|

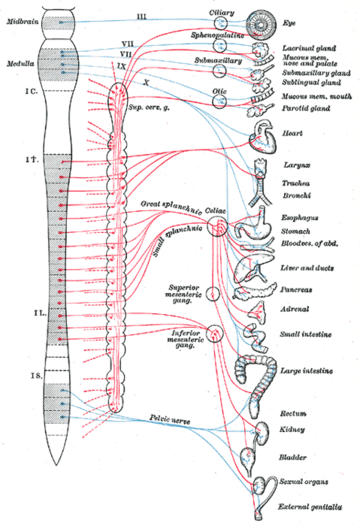

Autonomic nervous system innervation | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Autonomici systematis nervosi |

| TA | A14.3.00.001 |

| FMA | 9905 |

The autonomic nervous system (ANS), formerly the vegetative nervous system, is a division of the peripheral nervous system that supplies smooth muscle and glands, and thus influences the function of internal organs.[1] The autonomic nervous system is a control system that acts largely unconsciously and regulates bodily functions such as the heart rate, digestion, respiratory rate, pupillary response, urination, and sexual arousal.[2] This system is the primary mechanism in control of the fight-or-flight response.

Within the brain, the autonomic nervous system is regulated by the hypothalamus. Autonomic functions include control of respiration, cardiac regulation (the cardiac control center), vasomotor activity (the vasomotor center), and certain reflex actions such as coughing, sneezing, swallowing and vomiting. Those are then subdivided into other areas and are also linked to ANS subsystems and nervous systems external to the brain. The hypothalamus, just above the brain stem, acts as an integrator for autonomic functions, receiving ANS regulatory input from the limbic system to do so.[3]

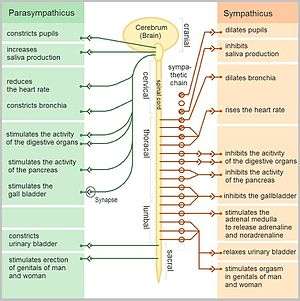

The autonomic nervous system has two branches: the sympathetic nervous system and the parasympathetic nervous system.[4] The sympathetic nervous system is often considered the "fight or flight" system, while the parasympathetic nervous system is often considered the "rest and digest" or "feed and breed" system. In many cases, both of these systems have "opposite" actions where one system activates a physiological response and the other inhibits it. An older simplification of the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems as "excitory" and "inhibitory" was overturned due to the many exceptions found. A more modern characterization is that the sympathetic nervous system is a "quick response mobilizing system" and the parasympathetic is a "more slowly activated dampening system", but even this has exceptions, such as in sexual arousal and orgasm, wherein both play a role.[3]

There are inhibitory and excitatory synapses between neurons. Relatively recently, a third subsystem of neurons that have been named non-noradrenergic, non-cholinergic transmitters (because they use nitric oxide as a neurotransmitter) have been described and found to be integral in autonomic function, in particular in the gut and the lungs.[5]

Although the ANS is also known as the visceral nervous system, the ANS is only connected with the motor side.[6] Most autonomous functions are involuntary but they can often work in conjunction with the somatic nervous system which provides voluntary control.

Structure

The autonomic nervous system is divided into the sympathetic nervous system and parasympathetic nervous system. The sympathetic division emerges from the spinal cord in the thoracic and lumbar areas, terminating around L2-3. The parasympathetic division has craniosacral “outflow”, meaning that the neurons begin at the cranial nerves (specifically the oculomotor nerve, facial nerve, glossopharyngeal nerve and vagus nerve) and sacral (S2-S4) spinal cord.

The autonomic nervous system is unique in that it requires a sequential two-neuron efferent pathway; the preganglionic neuron must first synapse onto a postganglionic neuron before innervating the target organ. The preganglionic, or first, neuron will begin at the “outflow” and will synapse at the postganglionic, or second, neuron’s cell body. The postganglionic neuron will then synapse at the target organ.

Sympathetic division

The sympathetic nervous system consists of cells with bodies in the lateral grey column from T1 to L2/3. These cell bodies are "GVE" (general visceral efferent) neurons and are the preganglionic neurons. There are several locations upon which preganglionic neurons can synapse for their postganglionic neurons:

- Paravertebral ganglia (3) of the sympathetic chain (these run on either side of the vertebral bodies)

- cervical ganglia (3)

- thoracic ganglia (12) and rostral lumbar ganglia (2 or 3)

- caudal lumbar ganglia and sacral ganglia

- Prevertebral ganglia (celiac ganglion, aorticorenal ganglion, superior mesenteric ganglion, inferior mesenteric ganglion)

- Chromaffin cells of the adrenal medulla (this is the one exception to the two-neuron pathway rule: the synapse is directly efferent onto the target cell bodies)

These ganglia provide the postganglionic neurons from which innervation of target organs follows. Examples of splanchnic (visceral) nerves are:

- Cervical cardiac nerves & thoracic visceral nerves, which synapse in the sympathetic chain

- Thoracic splanchnic nerves (greater, lesser, least), which synapse in the prevertebral ganglia

- Lumbar splanchnic nerves, which synapse in the prevertebral ganglia

- Sacral splanchnic nerves, which synapse in the inferior hypogastric plexus

These all contain afferent (sensory) nerves as well, known as GVA (general visceral afferent) neurons.

Parasympathetic division

The parasympathetic nervous system consists of cells with bodies in one of two locations: the brainstem (Cranial Nerves III, VII, IX, X) or the sacral spinal cord (S2, S3, S4). These are the preganglionic neurons, which synapse with postganglionic neurons in these locations:

- Parasympathetic ganglia of the head: Ciliary (Cranial nerve III), Submandibular (Cranial nerve VII), Pterygopalatine (Cranial nerve VII), and Otic (Cranial nerve IX)

- In or near the wall of an organ innervated by the Vagus (Cranial nerve X) or Sacral nerves (S2, S3, S4)

These ganglia provide the postganglionic neurons from which innervations of target organs follows. Examples are:

- The postganglionic parasympathetic splanchnic (visceral) nerves

- The vagus nerve, which passes through the thorax and abdominal regions innervating, among other organs, the heart, lungs, liver and stomach

Sensory neurons

The sensory arm is composed of primary visceral sensory neurons found in the peripheral nervous system (PNS), in cranial sensory ganglia: the geniculate, petrosal and nodose ganglia, appended respectively to cranial nerves VII, IX and X. These sensory neurons monitor the levels of carbon dioxide, oxygen and sugar in the blood, arterial pressure and the chemical composition of the stomach and gut content. They also convey the sense of taste and smell, which, unlike most functions of the ANS, is a conscious perception. Blood oxygen and carbon dioxide are in fact directly sensed by the carotid body, a small collection of chemosensors at the bifurcation of the carotid artery, innervated by the petrosal (IXth) ganglion. Primary sensory neurons project (synapse) onto “second order” visceral sensory neurons located in the medulla oblongata, forming the nucleus of the solitary tract (nTS), that integrates all visceral information. The nTS also receives input from a nearby chemosensory center, the area postrema, that detects toxins in the blood and the cerebrospinal fluid and is essential for chemically induced vomiting or conditional taste aversion (the memory that ensures that an animal that has been poisoned by a food never touches it again). All this visceral sensory information constantly and unconsciously modulates the activity of the motor neurons of the ANS.

Innervation

Autonomic nerves travel to organs throughout the body. Most organs receive parasympathetic supply by the vagus nerve and sympathetic supply by splanchnic nerves. The sensory part of the latter reaches the spinal column at certain spinal segments. Pain in any internal organ is perceived as referred pain, more specifically as pain from the dermatome corresponding to the spinal segment.[7]

| Organ | Nerves[8] | Spinal column origin[8] |

|---|---|---|

| stomach | T6, T7, T8, T9, sometimes T10 | |

| duodenum | T5, T6, T7, T8, T9, sometimes T10 | |

| jejunum and ileum | T5, T6, T7, T8, T9 | |

| spleen | T6, T7, T8 | |

| gallbladder and liver |

|

T6, T7, T8, T9 |

| colon |

|

|

| pancreatic head | T8, T9 | |

| vermiform appendix |

|

T10 |

| kidneys and ureters |

|

T11, T12 |

Motor neurons

Motor neurons of the autonomic nervous system are found in ‘’autonomic ganglia’’. Those of the parasympathetic branch are located close to the target organ whilst the ganglia of the sympathetic branch are located close to the spinal cord.

The sympathetic ganglia here, are found in two chains: the pre-vertebral and pre-aortic chains. The activity of autonomic ganglionic neurons is modulated by “preganglionic neurons” located in the central nervous system. Preganglionic sympathetic neurons are located in the spinal cord, at the thorax and upper lumbar levels. Preganglionic parasympathetic neurons are found in the medulla oblongata where they form visceral motor nuclei; the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus nerve; the nucleus ambiguus, the salivatory nuclei, and in the sacral region of the spinal cord.

Function

Sympathetic and parasympathetic divisions typically function in opposition to each other. But this opposition is better termed complementary in nature rather than antagonistic. For an analogy, one may think of the sympathetic division as the accelerator and the parasympathetic division as the brake. The sympathetic division typically functions in actions requiring quick responses. The parasympathetic division functions with actions that do not require immediate reaction. The sympathetic system is often considered the "fight or flight" system, while the parasympathetic system is often considered the "rest and digest" or "feed and breed" system.

However, many instances of sympathetic and parasympathetic activity cannot be ascribed to "fight" or "rest" situations. For example, standing up from a reclining or sitting position would entail an unsustainable drop in blood pressure if not for a compensatory increase in the arterial sympathetic tonus. Another example is the constant, second-to-second, modulation of heart rate by sympathetic and parasympathetic influences, as a function of the respiratory cycles. In general, these two systems should be seen as permanently modulating vital functions, in usually antagonistic fashion, to achieve homeostasis. Some typical actions of the sympathetic and parasympathetic systems are listed below.

Sympathetic nervous system

Promotes a fight-or-flight response, corresponds with arousal and energy generation, and inhibits digestion

- Diverts blood flow away from the gastro-intestinal (GI) tract and skin via vasoconstriction

- Blood flow to skeletal muscles and the lungs is enhanced (by as much as 1200% in the case of skeletal muscles)

- Dilates bronchioles of the lung through circulating epinephrine, which allows for greater alveolar oxygen exchange

- Increases heart rate and the contractility of cardiac cells (myocytes), thereby providing a mechanism for enhanced blood flow to skeletal muscles

- Dilates pupils and relaxes the ciliary muscle to the lens, allowing more light to enter the eye and enhances far vision

- Provides vasodilation for the coronary vessels of the heart

- Constricts all the intestinal sphincters and the urinary sphincter

- Inhibits peristalsis

- Stimulates orgasm

Parasympathetic nervous system

The parasympathetic nervous system has been said to promote a "rest and digest" response, promotes calming of the nerves return to regular function, and enhancing digestion. Functions of nerves within the parasympathetic nervous system include:

- Dilating blood vessels leading to the GI tract, increasing the blood flow.

- Constricting the bronchiolar diameter when the need for oxygen has diminished

- Dedicated cardiac branches of the vagus and thoracic spinal accessory nerves impart parasympathetic control of the heart (myocardium)

- Constriction of the pupil and contraction of the ciliary muscles, facilitating accommodation and allowing for closer vision

- Stimulating salivary gland secretion, and accelerates peristalsis, mediating digestion of food and, indirectly, the absorption of nutrients

- Sexual. Nerves of the peripheral nervous system are involved in the erection of genital tissues via the pelvic splanchnic nerves 2–4. They are also responsible for stimulating sexual arousal.

Neurotransmitters

At the effector organs, sympathetic ganglionic neurons release noradrenaline (norepinephrine), along with other cotransmitters such as ATP, to act on adrenergic receptors, with the exception of the sweat glands and the adrenal medulla:

- Acetylcholine is the preganglionic neurotransmitter for both divisions of the ANS, as well as the postganglionic neurotransmitter of parasympathetic neurons. Nerves that release acetylcholine are said to be cholinergic. In the parasympathetic system, ganglionic neurons use acetylcholine as a neurotransmitter to stimulate muscarinic receptors.

- At the adrenal medulla, there is no postsynaptic neuron. Instead the presynaptic neuron releases acetylcholine to act on nicotinic receptors. Stimulation of the adrenal medulla releases adrenaline (epinephrine) into the bloodstream, which acts on adrenoceptors, producing a widespread increase in sympathetic activity.

A full table is found at Table of neurotransmitter actions in the ANS.

Caffeine effects

Caffeine is a bio-active ingredient found in commonly consumed beverages such as coffee, tea, and sodas. Short-term physiological effects of caffeine include increased blood pressure and sympathetic nerve outflow. Habitual consumption of caffeine may inhibit physiological short-term effects. Consumption of caffeinated espresso increases parasympathetic activity in habitual caffeine consumers; however, decaffeinated espresso inhibits parasympathetic activity in habitual caffeine consumers. It is possible other bio-active ingredients in decaffeinated espresso may also contribute to the inhibition of parasympathetic activity in habitual caffeine consumers.[10]

Caffeine is capable of increasing work capacity while individuals perform strenuous tasks. In one study, caffeine provoked a greater maximum heart rate while a strenuous task was being performed compared to a placebo. This tendency is likely due to caffeine's ability to increase sympathetic nerve outflow. Furthermore, this study found that recovery after intense exercise was slower when caffeine was consumed prior to exercise. This finding is indicative of caffeine's tendency to inhibit parasympathetic activity in non-habitual consumers. The caffeine-stimulated increase in nerve activity is likely to evoke other physiological effects as the body attempts to maintain homeostasis. [11]

The effects of caffeine on parasympathetic activity may vary depending on the position of the individual when autonomic responses are measured. One study found that the seated position inhibited autonomic activity after caffeine consumption (75 mg); however, parasympathetic activity increased in the supine position. This finding may explain why some habitual caffeine consumers (75 mg or less) do not experience short-term effects of caffeine if their routine requires many hours in a seated position. It is important to note that the data supporting increased parasympathetic activity in the supine position was derived from an experiment involving participants between the ages of 25 and 30 who were considered healthy and sedentary. Caffeine may influence autonomic activity differently for individuals who are more active or elderly.[12]

Automatic analysis and assessment software

- NerveExpress - Quantitative assessment of the Autonomic Nervous System (ANS) based on Heart Rate Variability (HRV) analysis.

See also

References

- ↑ "autonomic nervous system" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary

- ↑ Schmidt, A; Thews, G (1989). "Autonomic Nervous System". In Janig, W. Human Physiology (2 ed.). New York, NY: Springer-Verlag. pp. 333–370.

- 1 2 Allostatic load notebook: Parasympathetic Function - 1999, MacArthur research network, UCSF

- ↑ Pocock, Gillian (2006). Human Physiology (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 63–64. ISBN 978-0-19-856878-0.

- ↑ Belvisi, Maria G.; David Stretton, C.; Yacoub, Magdi; Barnes, Peter J. (1992). "Nitric oxide is the endogenous neurotransmitter of bronchodilator nerves in humans". European Journal of Pharmacology. 210 (2): 221–2. PMID 1350993. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(92)90676-U.

- ↑ Costanzo, Linda S. (2007). Physiology. Hagerstwon, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 37. ISBN 0-7817-7311-3.

- ↑ Essential Clinical Anatomy. K.L. Moore & A.M. Agur. Lippincott, 2 ed. 2002. Page 199

- 1 2 Unless specified otherwise in the boxes, the source is: Moore, Keith L.; Agur, A. M. R. (2002). Essential Clinical Anatomy (2nd ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 199. ISBN 978-0-7817-5940-3.

- ↑ Neil A. Campbell, Jane B. Reece: Biologie. Spektrum-Verlag Heidelberg-Berlin 2003, ISBN 3-8274-1352-4

- ↑ Zimmerman-Viehoff, Frank; Thayer, Julian; Koenig, Julian; Herrmann, Christian; Weber, Cora S.; Deter, Hans-Christian (May 1, 2016). "Short-term effects of espresso coffee on heart rate variability and blood pressure in habitual and non-habitual coffee consumers- a randomized crossover study". Nutritional Neuroscience. 19 (4): 169–175. Retrieved February 20, 2017.

- ↑ Bunsawat, Kanokwan; White, Daniel W; Kappus, Rebecca M; Baynard, Tracy (2015). "Caffeine delays autonomic recovery following acute exercise". European Journal of Preventive Cardiology. 22 (11): 1473–1479. Retrieved February 20, 2017.

- ↑ Monda, M.; Viggiano, An.; Vicidomini, C.; Viggiano, Al.; Iannaccone, T.; Tafuri, D.; De Luca, B. (2009). "Expresso coffee increases parasympathetic activity in young, healthy people". Nutritional Neuroscience. 12 (1): 43–48. Retrieved February 20, 2017.

External links

- Autonomic nervous system article in Scholarpedia, by Ian Gibbins and Bill Blessing

- ANS Medical Notes on rahulgladwin.com

- NerveExpress is a fully automatic, non-invasive computer-based system designed for quantitative assessment of the Autonomic Nervous System (ANS) based on Heart Rate Variability (HRV) analysis.