Vieques, Puerto Rico

| Vieques, Puerto Rico | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Municipality | |||

|

Vieques from the air, looking west | |||

| |||

| Nickname(s): Isla Nena | |||

Location of Vieques in Puerto Rico | |||

| Coordinates: 18°07′N 65°25′W / 18.117°N 65.417°WCoordinates: 18°07′N 65°25′W / 18.117°N 65.417°W | |||

| Country | United States | ||

| Territory | Puerto Rico | ||

| Government | |||

| • Mayor | Víctor Emeric (PPD) | ||

| • Senatorial District | 8 - Carolina | ||

| • Representative District | 36 | ||

| Area | |||

| • Total | 134.42 sq mi (348.15 km2) | ||

| • Land | 52 sq mi (135 km2) | ||

| • Water | 82.30 sq mi (213.15 km2) | ||

| Population (2010) | |||

| • Total | 9,301 | ||

| • Density | 69/sq mi (27/km2) | ||

| Demonym(s) | Viequenses | ||

| Racial groups[1] | |||

| • White | 72.7% | ||

| • Black | 13.8% | ||

| • American Indian/AN | 0.4% | ||

| • Asian - Native Hawaiian/Pi |

0.6% 0.8% | ||

| • Other Two or more races |

8.8% 3.4% | ||

| Time zone | AST (UTC-4) | ||

| Zip code | 00765 | ||

Vieques (/viːˈeɪkɪs/; Spanish pronunciation: [ˈbjekes], locally [ˈbjẽke]), in full Isla de Vieques, is an island–municipality of Puerto Rico (U.S.) in the northeastern Caribbean, part of an island grouping sometimes known as the Spanish Virgin Islands. Vieques is part of the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, and retains strong influences from 400 years of Spanish presence in the island.

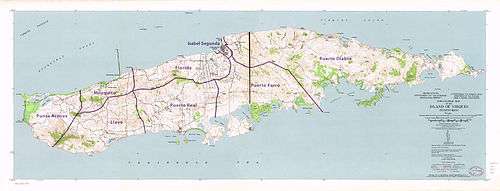

Vieques lies about 8 miles (13 km) east of the Puerto Rican mainland, and measures about 21 miles (34 km) long by 4 miles (6 km) wide. Its most populated barrio is Isabel Segunda (sometimes written "Isabel II"), the administrative center on the northern side of the island. The population of Vieques was 9,301 at the 2010 Census.

The island's name is a Spanish spelling of an American Indian word (likely Taíno) said to mean "small island". It also has the nickname "Isla Nena", usually translated from the Spanish as "Little Girl Island", alluding to its perception as Puerto Rico's little sister. During the colonial period, the British name was "Crab Island".

Vieques is best known internationally as the site of a series of protests against the United States Navy's use of the island as a bombing range and testing ground, which led to the navy's departure in 2003. Today the former navy land is a national wildlife refuge, with numerous beaches that still retain the names given by the navy, including Red Beach, Blue Beach and Green Beach. The beaches are commonly listed among the top beaches in the Caribbean for their azure-colored waters and white sands.

History

Pre-Columbian history

Archaeological evidence suggests that Vieques was first inhabited by ancient American Indian peoples who traveled from continental America perhaps between 3000 BC and 2000 BC. However, estimates of these prehistoric dates of inhabitation vary widely. These tribes had a Stone Age culture and were probably fishermen and hunter-gatherers.

Excavations at the Puerto Ferro site by Luis Chanlatte and Yvonne Narganes[2] uncovered a fragmented human skeleton in a large hearth area. Radiocarbon dating of shells found in the hearth indicate a burial date of c.1900 BCE. This skeleton, popularly known as El Hombre de Puerto Ferro, was buried at the center of a group of large boulders near the south-central coast of Vieques, approximately one kilometer northwest of the Bioluminescent Bay. Linear arrays of smaller stones radiating from the central boulders are apparent at the site today, but their age and reason for placement are unknown.

Further waves of settlement by Native Americans followed over many centuries. The Arawak-speaking Saladoid (or Igneri) people, thought to have originated in modern-day Venezuela, arrived in the region perhaps around 200 BC (again estimates vary). These tribes, noted for their pottery, stone carving, and other artifacts, eventually merged with groups from Hispaniola and Cuba, to form what is now called the Taíno culture. This culture flourished in the region from around 1000 AD, and survived on Vieques until the arrival of the Europeans in the late 15th century.

Spanish colonial period

The European discovery of Vieques is sometimes credited to Christopher Columbus, who landed in Puerto Rico in 1493. It does not seem to be certain whether Columbus personally visited Vieques, but in any case the island was soon claimed by the Spanish. During the early 16th century Vieques became a center of Taíno rebellion against the European invaders, prompting the Spanish to send armed forces to the island to quell the resistance. The native Taíno population was decimated, and its people either killed, imprisoned or enslaved by the Spanish.

The Spanish did not, however, permanently colonise Vieques at this time, and for the next three hundred years it remained a lawless outpost, frequented by pirates and outlaws. As European powers fought for control in the region, a series of attempts by the French, English and Danish to colonise the island in the 17th and 18th centuries were repulsed by the Spanish. The island also received considerable attention as a possible colony from Scotland, and after numerous attempts to buy the island proved unsuccessful, the Scottish fleet, en route to Darien in 1698, made landfall and took possession of the island in the name of the Company of Scotland Trading to Africa and The Indies. Scottish sovereignty of the island proved short-lived however, as a Danish ship arrived shortly afterwards and claimed the island.

At the beginning of the 19th century, the Spanish took steps to permanently settle and secure the island. In 1811, Don Salvador Meléndez, then governor of Puerto Rico, sent military commander Juan Rosselló to begin what would become the annexation of Vieques by the Puerto Ricans.[3] In 1832, under an agreement with the Spanish Puerto Rican administration, Frenchman Teófilo José Jaime María Le Guillou became Governor of Vieques, and undertook to impose order on the anarchic province. He was instrumental in the establishment of large plantations, marking a period of social and economic change for the island. Le Guillou is now remembered as the "founder" of Vieques (though this title is also sometimes conferred on Francisco Saínz, governor from 1843 to 1852, who founded Isabel Segunda, the "town of Vieques", named after Queen Isabel II of Spain). Vieques was formally annexed to Puerto Rico in 1854.

In 1816, Vieques was briefly visited by Simón Bolívar when his ship ran aground there while fleeing defeat in Venezuela.[4]

During the second part of the 19th century, thousands of black immigrants came to Vieques to work on the sugarcane plantations. They arrived from the nearby islands of St. Thomas, Nevis, St. Kitts, St. Croix, and many other Caribbean islands, some of them arrived as slaves and some as independent economic migrants. By the time of settlement of Vieques the Eastern Caribbean was post-Emancipation but some arrived as contract labor. Since this time black people have formed an important part of Vieques’ society.

United States control

In 1898, after Spain's defeat in the Spanish–American War, Vieques, along with mainland Puerto Rico, was ceded to the United States.

In the 1920s and 1930s, the sugar industry, on which Vieques was totally dependent, went into decline due to falling sugar prices and industrial unrest. Many locals were forced to move to mainland Puerto Rico or Saint Croix to look for work.

In 1941, while Europe was in the midst of World War II, the United States Navy purchased or seized about two thirds of Vieques as an extension to the Roosevelt Roads Naval Station nearby on the Puerto Rican mainland. The original purpose of the base (never implemented) was to provide a safe haven for the British fleet should Britain fall to Nazi Germany. Much of the land was bought from the owners of large farms and sugar cane plantations, and the purchase triggered the final demise of the sugar industry. Many agricultural workers, who had no formal title to the land they occupied, were evicted.[5]

After the war, the US Navy continued to use the island for military exercises, and as a firing range and testing ground for munitions.

Protests and departure of the United States Navy

The continuing post-war presence in Vieques of the United States Navy drew protests from the local community, angry at the expropriation of their land and the environmental impact of weapons testing. The locals' discontent was exacerbated by the island's perilous economic condition.

Protests came to a head in 1999 when Vieques native David Sanes, a civilian employee of the United States Navy, was killed by a jet bomb that the Navy said misfired. Sanes had been working as a security guard. A popular campaign of civil disobedience resurged; not since the mid-1970s had Viequenses come together en masse to protest the target practices.[6] The locals took to the ocean in their small fishing boats and successfully stopped the US Navy's military exercises.

The Vieques issue became something of a cause célèbre, and local protesters were joined by sympathetic groups and prominent individuals from the mainland United States and abroad, including political leaders Rubén Berríos, Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., Al Sharpton and Jesse Jackson, singers Danny Rivera, Willie Colón[7] and Ricky Martin, actors Edward James Olmos and Jimmy Smits, boxer Félix 'Tito' Trinidad, baseball superstar Carlos Delgado, writers Ana Lydia Vega and Giannina Braschi, and Guatemala's Nobel Prize winner Rigoberta Menchú. Kennedy's son, Aidan Caohman "Vieques" Kennedy,[8] was born while his father served jail time in Puerto Rico for his role in the protests. The problems arising from the US Navy base have also featured in songs by various musicians, including Puerto Rican rock band Puya, rapper Immortal Technique and reggaeton artist Tego Calderón. In popular culture, one subplot of "The Two Bartlets" episode of The West Wing dealt with a protest on the bombing range led by a friend of White House Deputy Chief of Staff Josh Lyman; this character was modeled on future West Wing star Jimmy Smits, a native of Puerto Rico who was repeatedly arrested for his leading of protests there.

As a result of this pressure, in May 2003 the Navy withdrew from Vieques, and much of the island was designated a National Wildlife Refuge under the control of the United States Fish and Wildlife Service. Closure of Roosevelt Roads Naval Station followed in 2004.

Government

Vieques is a municipio of Puerto Rico, translated as "municipality" and in this context roughly equivalent to "township". It is in the Puerto Rican electoral district of Carolina. Local government is under the leadership of a mayor, presently Víctor Emeric.

The city belongs to the Puerto Rico Senatorial district VIII, which is represented by two Senators. In 2012, Pedro A. Rodríguez and Luis Daniel Rivera were elected as District Senators.[9]

Administrative divisions

with wards (barrios)

Administratively Vieques is divided into eight wards (barrios), including the town of Isabel Segunda:

| Barrio | Area (m²)[10] | Population (census 2000) | Density | Islands in barrio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isabela II barrio-pueblo | 696997 | 1459 | 2093.3 | — |

| Florida | 11553856 | 4126 | 357.1 | — |

| Llave | 15420815 | 8 | 0.5 | — |

| Mosquito | 6279364 | 0 | 0.0 | — |

| Puerto Diablo | 45323702 | 984 | 21.7 | Roca Cucaracha, Isla Yallis, Roca Alcatraz, Cayo Conejo, Cayo Jalovita, Cayo Jalova |

| Puerto Ferro | 21199791 | 856 | 40.4 | Isla Chiva, Cayo Chiva |

| Puerto Real | 19943599 | 1673 | 83.9 | Cayo de Tierra, Cayo de Afuera (Cayo Real) |

| Punta Arenas | 11227244 | 0 | 0.0 | — |

| Vieques | 131645368 | 9106 | 69.2 |

Geography

Vieques measures about 21 miles (34 km) east-west, and three to four miles (5 km) north-south. It has a land area of 52 square miles (130 km2) and is located about ten miles (16 km) to the east of Puerto Rico. To the north of Vieques is the Atlantic Ocean, and to the south the Caribbean. The island of Culebra is about 10 miles (16 km) north of Vieques, and the US Virgin Islands lie to the east. Vieques and Culebra, together with various small islets, make up the so-called Spanish Virgin Islands, sometimes known as the Passage Islands.

The former US Navy lands, now wildlife reserves, occupy the entire eastern and western ends of Vieques, with the former live weapons testing site (known as the "LIA", or "Live Impact Area") at the extreme eastern tip.[11] These areas are unpopulated. The former civilian area occupies very roughly the central third of the island and contains the towns of Isabel Segunda on the north coast, and Esperanza on the south.

Vieques has a terrain of rolling hills, with a central ridge running east-west. The highest point is Monte Pirata ("Pirate Mount") at 987 feet (300 m). Geologically the island is composed of a mixture of volcanic bedrock, sedimentary rocks such as limestone and sandstone, and alluvial deposits of gravel, sand, silt, and clay. There are no permanent rivers or streams. Much former agricultural land has been reclaimed by nature due to prolonged disuse, and, apart from some small-scale farming in the central region, the island is largely covered by brush and subtropical dry forest. Around the coast lie palm-fringed sandy beaches interspersed with lagoons, mangrove swamps, salt flats and coral reefs.

A series of nearshore islets and rocks are part of the municipality of Vieques, clockwise starting at the northernmost:

- Roca Cucaracha (a rock with less than five meters in diameter)

- Isla Yallis

- Roca Alcatraz

- Cayo Conejo

- Cayo Jalovita

- Cayo Jalova

- Isla Chiva

- Cayo Chiva

- Cayo de Tierra

- Cayo de Afuera (Cayo Real)

Bioluminescent Bay

The Bioluminescent Bay (also known as Puerto Mosquito, Mosquito Bay, or "The Bio Bay"), is considered the best example of a bioluminescent bay in the United States and is listed as a national natural landmark, one of five in Puerto Rico. The luminescence in the bay is caused by a micro-organism, the dinoflagellate Pyrodinium bahamense, which glows whenever the water is disturbed, leaving a trail of neon blue.

A combination of factors creates the necessary conditions for bioluminescence: red mangrove trees surround the water (the organisms have been related to Mangrove forest [12] although Mangrove is not necessarily associated with this species [13]); a complete lack of modern development around the bay; the water is cool enough and deep enough; and a small channel to the ocean keeps the dinoflagellates in the bay. This small channel was created artificially, being the result of attempts by the occupants of Spanish ships to choke off the bay from the ocean. The Spanish believed that the bioluminescence they encountered there while first exploring the area, was the work of the devil ('El Diablo') and tried to block ocean water from entering the bay by dropping huge boulders in the channel. The Spanish only succeeded in preserving and increasing the luminescence in the now isolated bay.

Kayaking is permitted in the bay and may be arranged through local vendors.

Climate

Vieques has a warm, relatively dry, tropical to sub-tropical climate. Temperatures vary little throughout the year, with average daily maxima ranging from 82 °F (28 °C) in January to 87 °F (31 °C) in July.[14] Average daily minima are about 10 °F (6 °C) lower. Rainfall averages around 45 to 55 inches (1150 to 1400 mm) per year, with the months of May and September–November being the wettest. The west of the island receives significantly more rainfall than the east. Prevailing winds are easterly.

Vieques is prone to tropical storms and at risk from hurricanes from June to November. In 1989 Hurricane Hugo caused considerable damage to the island.[15]

Demographics

According to the 2010 US census,[16] the total population of Vieques was 9,301. 94.3% of the population are Hispanic or Latino (of any race). Natives of Vieques are known as Viequenses.

| Race (self-defined) Vieques Puerto Rico - 2010 Census[17] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Race | Population | % of Total |

| White | 5,456 | 58.7% |

| Black/Afro-Puerto Rican | 2,617 | 28.1% |

| American Indian and Alaska Native | 62 | 0.7% |

| Asian | 6 | 0.1% |

| Native Hawaiian Pacific Islander | 0 | 0% |

| Some other race | 688 | 7.4% |

| Two or more races | 309 | 3.4% |

Language

Both Spanish and English are recognized as official languages. Spanish is the primary language of most inhabitants.

Economy

The sugar industry, once the mainstay of the island's economy, declined during the early decades of the twentieth century, and finally collapsed in the 1940s when the US Navy took over much of the land on which the sugar cane plantations stood. After an initial naval construction phase, opportunities for making a living on the island were largely limited to fishing or subsistence farming on reduced area. Crops grown on the island include avocados, bananas, coconuts, grains, papayas and sweet potatoes. A small number of permanent local jobs were provided by the US Navy. Since the 1970s General Electric has employed a few hundred workers at a manufacturing plant. Unemployment was widespread, with consequent social problems. The 2000 US census reported a median household income in 1999 dollars of $9,331 (compared to $41,994 for the USA as a whole), and 35.8% of the population of 16 years and over in the labor force (compared to 63.9% for the USA as a whole).[16]

Like the rest of Puerto Rico, the island's currency is the US dollar.

Following the 2003 departure of the US Navy, efforts have been made to redevelop the island's agricultural economy, to clean up contaminated areas of the former bombing ranges, and to develop Vieques as a tourist destination. The Navy clean-up is currently the largest employer on the island, and has contributed over 20 million dollars directly into the local economy over the last 5 years through salaries, housing, vehicles, taxes, and services. The Navy has provided specialized training to several local islanders, who may be able to parlay this training into a career after the clean-up is over.

Tourism

aka Playa Caracas(Caracas Beach)

also called Red Beach a name given to the beach by U.S. NAVY and used mostly by English speakers

For sixty years the majority of Vieques was closed off by the US Navy, and the island remained almost entirely undeveloped for tourism. This lack of development is now marketed as a key attraction. Vieques is promoted under an ecotourism banner as a sleepy, unspoiled island of rural "old world" charm and pristine deserted beaches, and is rapidly becoming a popular destination.

Since the Navy's departure, tensions on the island have been low, although land speculation by foreign developers and fears of overdevelopment have caused some resentment among local residents, and there are occasional reports of lingering anti-American sentiment.[18]

The lands previously owned by the Navy have been turned over to the U.S. National Fish and Wildlife Service and the authorities of Puerto Rico and Vieques for management. The immediate bombing range area on the eastern tip of the island suffers from severe contamination, but the remaining areas are mostly open to the public, including many beautiful beaches that were inaccessible to civilians while the military was conducting training maneuvers.

Snorkeling is excellent, especially at Blue Beach (Bahía de la Chiva). Aside from archeological sites, such as La Hueca, and deserted beaches, a unique feature of Vieques is the presence of two pristine bioluminescent bays, including Mosquito Bay. Vieques is also famous for its feral paso fino horses, which roam free over parts of the island.[18] These are descended from stock originally brought by European colonisers.

In 2011, TripAdvisor listed Vieques among the Top 25 Beaches in the World, writing "If you prefer your beaches without the accompanying commercial developments, Isla de Vieques is your tanning turf, with more than 40 beaches and not one traffic light."[19]

Landmarks and places of interest

- Fortín Conde de Mirasol (Count Mirasol Fort), a fort built by the Spanish in the mid 19th century, now a museum

- Playa Esperanza (Esperanza Beach)

- The tomb of Le Guillou, the town founder, in Isabel Segunda

- La Casa Alcaldía (City Hall)

- Faro Punta Mulas, built in 1896

- Faro de Puerto Ferro

- Sun Bay Beach

- The Bioluminescent Bay

- The 300-year-old ceiba tree

- Rompeolas (Mosquito Pier), renamed Puerto de la Libertad David Sanes Rodríguez in 2003

- Puerto Ferro Archaeological Site

- Black Sand Beach

- Hacienda Playa Grande (Old Sugarcane Plantation Building)

- Underground U.S. Navy Bunkers

- Wreckage of the World War II Navy Destroyer USS Killen (DD593)

Culture

Festivals and events

- Festival de los Reyes Magos (Epiphany Festival) – January 6

- Via Crucis (Passion Play) – Holy Week

- Festival Cultural Viequense (Vieques Cultural Festival) – March/April

- Fiestas Patronales (Traditional Town Festivities) – July

- Puerto Rico International Film Festival Vieques (Annual International Film Festival) – June

- Trova Navideña (Christmas Troubador Night) – December

- Festival Navideño (Christmas Festival) – December–January

Transportation

Vieques is served by Antonio Rivera Rodríguez Airport, which currently accommodates only small propeller-driven aircraft. Services to the island run from San Juan's Luis Muñoz Marín International Airport, Ceiba Airport or Isla Grande Airport (20- to 30-minute flight). Flights are also available between Vieques and Saint Croix and Saint Thomas.

Also, a ferry runs from Fajardo several times a day. The ferry service is administered by the Autoridad de Transporte Marítimo (ATM) in Puerto Rico.[20]

Public health

There have been claims linking Vieques' higher cancer rate[21] to the long history of US weapons testing on the island.

Milivi Adams was a girl from Vieques who developed and died of cancer and became a symbol in the battle against the presence of the military.[22][23] Her face had appeared many times on the covers of Puerto Rican newspapers and magazines, and there were posters with her picture on them on many of Vieques' street corners. The daughter of Zuleyka Calderon and Jose Adams,[24] Milivi was diagnosed with cancer at the age of two years. Although many people blamed the military's bomb testings in Vieques as the source of her cancer, this has not been proven.[25] Given a month to live at the age of three, her cancer went into remission, but at the age of four reappeared, in her brain. She was flown to the United States by her parents, in hopes that treatment would help her; she fought infections, and after the last one, doctors told her parents that her body would not resist another infection treatment. She returned to Puerto Rico, where she died on the morning of November 17, 2002.[26]

Nayda Figueroa, an epidemiologist for Puerto Rico's Cancer Registry, stated that research showed Vieques' cancer rate from 1995 to 1999 was 31 percent higher than for the main island.

Michael Thun, head of epidemiological research at the American Cancer Society, cautioned that the variations in the rates could be attributed to chance, given the small population on Vieques.[27] A 2000 Nuclear Regulatory Commission report concluded that "the public had not been exposed to depleted uranium contamination above normal background (naturally occurring) levels".[28]

Surveys of the wreckage of a target ship in a shallow bay at the bombing range, however, revealed its identity to be that of the USS Killen, a target ship in nuclear tests in the Pacific in 1958. By 2002, it was evident that thousands of tons of steel that had originally been irradiated in the 1958 nuclear tests was missing from the wreckage in the bay. That steel has been missing for over 35 years and is still unaccounted for by the US Navy, Environmental Protection Agency and US Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR). Hundreds of steel drums of unknown origin were found among the wreckage. Their identity and contents have not been adequately verified.

In response to concerns about potential contamination from toxic metals and other chemicals, the ATSDR conducted a number of surveys in 1999–2002 to test Vieques' soil, water supply, air, fish and shellfish for harmful substances. The general conclusion of the ATSDR survey was that no public health hazard existed as a result of the Navy's activities.[28] However, scientists have pointed out that fish samples were drawn from local markets, which often import fish from other areas. Also sample sizes from each location were too small to provide compelling evidence for the lack of a public health danger (Wargo, Green Intelligence). The conclusions of the ATSDR report have more recently, as of 2009, been questioned and discredited. A review is underway.[29][30][31]

Casa Pueblo, a Puerto Rican environmental group, reports a study of the flora and fauna of Vieques that "clearly demonstrates sequestration of high levels of toxic elements in plant and animal tissue samples", and that "Consecuently [sic], the ecological food web of the Vieques Island has been adversely impacted."[32]

Notable natives and residents

- Jaime Rexach Benitez, educator, politician and humanist;

- Nelson Dieppa, professional boxer;

- Juan Francisco Luis, Governor of the U.S. Virgin Islands (1978–1987);

- Germán Rieckehoff Sampayo, was president of the Puerto Rican Olympic committee;

- Carlos Vélez Rieckehoff, local nationalist leader and political activist;

- Andres Santiago Jr. Sergeant First Class, US Army

- Manuel A. Romero, notable attorney and former President of the Brooklyn Bar Association

Gallery

Sun Bay

Sun Bay A view towards Navío Beach from a nearby sea cave

A view towards Navío Beach from a nearby sea cave A view from the Malecón (promenade) in Esperanza towards Cayo de Afuera

A view from the Malecón (promenade) in Esperanza towards Cayo de Afuera Playa Caracas (Red Beach)

Playa Caracas (Red Beach) Navío Beach

Navío Beach Festival Viequense (2007)

Festival Viequense (2007) Esperanza Beach

Esperanza Beach

See also

- List of Puerto Ricans

- History of Puerto Rico

- Did you know-Puerto Rico?

- United States Navy in Vieques, Puerto Rico

- List of Vieques birds

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Vieques

- Kahoolawe

- Vieques National Wildlife Refuge

- Culebra, Puerto Rico

References

- ↑ "2000 Decennial Profiles" (PDF). Retrieved 2011-06-13.

- ↑ American Antiquity, Vol. 57, No. 1 (Jan. 1992) pp. 146-163.

- ↑ Mullenneaux, Lisa (2000). Ni Una Bomba Más!: Vieques Vs. U.S. Navy. Penington Press. p. 22. ISBN 9780970429605.

- ↑ Keeling, Stephen (2008). The Rough Guide to Puerto Rico. Penguin. p. 162. ISBN 9781858283548.

- ↑ "From Sugar Plantations to Military Bases: the U.S. Navy's Expropriations in Vieques, Puerto Rico", César Ayala.

- ↑ Puerto Rico under Colonial Rule: Political Persecution and the Quest for Human Rights, SUNY Press, 2006.

- ↑ http://www.williecolon.com/vieques/campamentoberrios/fslide11.htm

- ↑ http://articles.sun-sentinel.com/2001-07-28/news/0107280098_1_vieques-kennedy-bodyguard

- ↑ Elecciones Generales 2012: Escrutinio General on CEEPUR

- ↑ - American FactFinder "Detailed Tables - American Factfinder" Check

|url=value (help). Factfinder.census.gov. Retrieved 2010-08-28. - ↑ McCaffrey, Katherine T. (2009). "Environmental Struggle After the Cold War: New Forms of Resistance to the U.S. Military in Vieques, Puerto Rico". In Lutz, Catherine. Bases of Empire: The Global Struggle Against U.S. Military Posts. New York University Press. ISBN 9780814752432.

- ↑ Usup G, Azanza RV (1998) Physiology and dynamics of the tropical dinoflagellate Pyrodinium bahamense. In: Anderson DM, Cembella AD, Hallegraeff GM (eds) The physiological ecology of harmful algal blooms. NATO ASI Series, Springer-Verlag, Berlin, p 81–94

- ↑ Phlips, EJ, Badylak, S, Bledsoe, E & M Cichra. 2006. Factors affecting the distribution of Pyrodinium bahamense var. bahamense in coastal waters of Florida. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 322: 99-115.

- ↑ "weatherbase.com". weatherbase.com. Retrieved 2011-06-13.

- ↑ "U.S. Geological Survey report". Marine.usgs.gov. Retrieved 2011-06-13.

- 1 2 "US Census (2000)". Retrieved 2007-04-17.

- ↑ Black per. in PR

- 1 2 "Unpretentious Vieques, an island in transition". Boston Globe. 7 January 2007. Retrieved 7 January 2014.

- ↑ Top 25 Beaches in the World on TripAdvisor

- ↑ Vieques.com. "Passenger & Cargo Ferry Guide, Vieques & Fajardo, Puerto Rico". Retrieved October 16, 2013.

- ↑ "Rullan: Studies On Cancer In Vieques Reflect Increase". Puerto Rico Herald. Retrieved 2011-06-13.

- ↑ "Los Protagonistas de Vieques" [The Protagonists of Vieques] (PDF) (in Spanish). Retrieved June 16, 2014.

- ↑ Snodgrass, Mary Ellen (2009). Civil Disobedience: An Encyclopedic History of Dissidence in the United States. Sharpe Reference. p. 319. ISBN 978-0-7656-8127-0.

- ↑ "Milivi Adams Dies Another victim of the US military". Campaign for the Accountability of American Bases. 17 November 2002. Archived from the original on March 11, 2007. Retrieved June 16, 2014.

- ↑ "'Patriot Act' aimed at protesters". WorkersWorld Paper. Feb 7, 2002. Archived from the original on January 1, 1970. Retrieved June 16, 2014.

- ↑ "Brief History, Isla de Vieques, Puerto Rico". Vieques Tourism Office. Retrieved June 16, 2014.

- ↑ "Vieques Cancer Rate an Issue". Miami Herald. Archived from the original on March 11, 2007. Retrieved 2007-04-17.

- 1 2 "Soil Pathway Evaluation, Isla de Vieques Bombing Range". Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. Archived from the original on October 12, 2006. Retrieved 2007-04-17.

- ↑ "New Battle on Vieques, Over Navy's Cleanup of Munitions", Mireya Navarro, New York Times, Aug 6, 2009

- ↑ "Navy's Vieques Training May Be Tied to Health Risks", Mireya Navarro, New York Times, Nov 13, 2009

- ↑ "Reversal Haunts Federal Health Agency", Mireya Navarro, New York Times, Nov 29, 2009

- ↑ "Casa Pueblo report". Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved 2007-04-17.

External links

- Vieques, Puerto Rico: ATSDR Documents Dealing with the Isla de Vieques Bombing Range

- Welcome to Puerto Rico! Vieques

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Vieques. |

![]() Media related to Vieques, Puerto Rico at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Vieques, Puerto Rico at Wikimedia Commons

.png)