Alpaca

| Alpaca | |

|---|---|

| |

| Alpaca | |

| Domesticated | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Synapsida |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Family: | Camelidae |

| Genus: | Vicugna |

| Species: | V. pacos |

| Binomial name | |

| Vicugna pacos (Linnaeus, 1758) | |

| | |

| Alpaca range | |

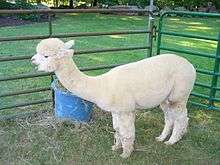

An alpaca (Vicugna pacos) is a domesticated species of South American camelid. It resembles a small llama in appearance.

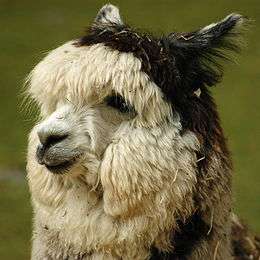

There are two breeds of alpaca; the Suri alpaca and the Huacaya alpaca.

Alpacas are kept in herds that graze on the level heights of the Andes of southern Peru, western Bolivia, Ecuador, and northern Chile at an altitude of 3,500 m (11,500 ft) to 5,000 m (16,000 ft) above sea level, throughout the year.[1] Alpacas are considerably smaller than llamas, and unlike llamas, they were not bred to be beasts of burden, but were bred specifically for their fibre. Alpaca fiber is used for making knitted and woven items, similar to wool. These items include blankets, sweaters, hats, gloves, scarves, a wide variety of textiles and ponchos in South America, and sweaters, socks, coats and bedding in other parts of the world. The fibre comes in more than 52 natural colors as classified in Peru, 12 as classified in Australia and 16 as classified in the United States.

In the textile industry, "alpaca" primarily refers to the hair of Peruvian alpacas, but more broadly it refers to a style of fabric originally made from alpaca hair, but now often made from similar fibers, such as mohair, Icelandic sheep wool, or even high-quality wool. In trade, distinctions are made between alpacas and the several styles of mohair and luster.[2]

An adult alpaca generally is between 81–99 centimetres (32–39 in) in height at the shoulders (withers). They usually weigh 48–84 kilograms (106–185 lb).

Background

Alpacas have been domesticated for thousands of years. The Moche people of northern Peru often used alpaca images in their art.[3] There are no known wild alpacas, and its closest living relative, the vicuña (also native to South America), are believed to be the wild ancestor of the alpaca.[4] The alpaca is larger than the vicuña, but smaller than the other camelid species.

Along with camels and llamas, alpacas are classified as camelids. Of the various camelid species, the alpaca and vicuña are the most valuable fiber-bearing animals: the alpaca because of the quality and quantity of its fiber, and the vicuña because of the softness, fineness and quality of its coat.[2]

Alpacas are too small to be used as pack animals. Instead, they are bred exclusively for their fiber and meat. Alpaca meat was once considered a delicacy by Andean inhabitants. Because of the high price commanded by alpaca on the growing North American alpaca market, illegal alpaca smuggling has become a growing problem.[5] In 2014, a company was formed claiming to be the first to export US-derived alpaca products to China.[6]

Alpacas and llamas can successfully cross-breed. The resulting offspring are called huarizo, which are valued for their unique fleece and gentle dispositions.

Behavior

Alpacas are social herd animals that live in family groups consisting of a territorial alpha male, females and their young. Alpacas warn the herd about intruders by making sharp, noisy inhalations that sound like a high-pitched bray. The herd may attack smaller predators with their front feet, and can spit and kick. Their aggression towards members of the canid family (coyotes, foxes, dogs etc.) is exploited when alpacas are used as guard llamas for guarding sheep.[7]

Spitting

Not all alpacas spit, but all are capable of doing so. "Spit" is somewhat euphemistic; occasionally the projectile contains only air and a little saliva, although alpacas commonly bring up acidic stomach contents (generally a green, grassy mix) and project it onto their chosen targets. Spitting is mostly reserved for other alpacas, but an alpaca will occasionally spit at a human.

For alpacas, spitting results in what is called "sour mouth". Sour mouth is characterized by a loose-hanging lower lip and a gaping mouth. This is caused by the stomach acids and unpleasant taste of the contents as they pass out of the mouth.

Hygiene

Alpacas use a communal dung pile, where they do not graze. This behaviour tends to limit the spread of internal parasites. Generally, males have much tidier, and fewer dung piles than females, which tend to stand in a line and all go at once. One female approaches the dung pile and begins to urinate and/or defecate, and the rest of the herd often follows.

Because of their preference for using a dung pile, some alpacas have been successfully house-trained.

Sounds

Alpacas make a variety of sounds. When they are in danger, they make a high-pitched, shrieking whine. Some breeds are known to make a "wark" noise when excited. Strange dogs – and even cats – can trigger this reaction. To signal friendly or submissive behavior, alpacas "cluck", or "click", a sound possibly generated by suction on the soft palate, or possibly in the nasal cavity.

Individuals vary, but most alpacas generally make a humming sound. Hums are often comfort noises, letting the other alpacas know they are present and content. The humming can take on many inflections and meanings.

When males fight, they make a warbling, bird-like cry, presumably intended to terrify the opponent.

Reproduction

Females are induced ovulators;[8] the act of mating and the presence of semen causes them to ovulate. Females usually conceive after just one breeding, but occasionally do have trouble conceiving. Artificial insemination is technically difficult, but it can be accomplished. Alpacas conceived from artificial insemination are not registerable with the Alpaca Registry.[9]

A male is usually ready to mate for the first time between two and three years of age. A female alpaca may fully mature (physically and mentally) between 10 and 24 months. It is not advisable to allow a young female to be bred until she is mature, and has reached two-thirds of her mature weight. Over-breeding a young female before conception is possible is a common cause of uterine infections. As the age of maturation varies greatly between individuals, it is usually recommended that novice breeders wait until females are 18 months of age or older before initiating breeding.[10]

The gestation period is, on average, 11.5 months, and usually results in a single offspring, or cria. Twins are rare, occurring about once per 1000 deliveries.[11] Cria are generally between 15 and 19 pounds, and are standing 30 to 90 minutes after birth.[12] After a female gives birth, she is generally receptive to breeding again after about two weeks. Crias may be weaned through human intervention at about six months old and 60 pounds, but many breeders prefer to allow the female to decide when to wean her offspring; they can be weaned earlier or later depending on their size and emotional maturity.

Alpacas can live for up to 25 years.

Diet

Alpacas require much less food than most animals of their size. They generally eat hay or grasses, but can eat some other plants (e.g. some leaves), and will normally try to chew on almost anything (e.g. empty bottle). Most alpaca ranchers rotate their feeding grounds so the grass can regrow and fecal parasites may die before reusing the area.

Alpacas can eat natural unfertilized grass; however, ranchers can also supplement grass with low-protein grass hay. To provide selenium and other necessary vitamins, ranchers will feed their domestic alpacas a daily dose of grain.[13] Free-range alpacas may obtain the necessary vitamins in their native grazing ranges.

Digestion

Alpacas are pseudoruminants and, like other camelids, have a three-chambered stomach; combined with chewing cud, this three-chambered system allows maximum extraction of nutrients from low-quality forages.[14]

Alpacas will chew their food in a figure eight motion, swallow the food, and then pass it into one of the stomach's chambers. The first and second chambers (called C1 and C2) are where the fermentation process begins digestion. The alpaca will further absorb nutrients and water in the first part of the third chamber. The end of the third chamber (called C3) is where the stomach secretes acids to digest food, and is the likely place where an alpaca will have ulcers, if stressed. The alpaca digestive system is very sensitive and must be kept healthy and balanced.[15]

Poisonous plants

Many plants are poisonous to the alpaca, including the bracken fern, fireweed, oleander, and some azaleas. In common with similar livestock, others include: acorns, African rue, agave, amaryllis, autumn crocus, bear grass, broom snakeweed, buckwheat, ragweed, buttercups, calla lily, orange tree foliage, carnations, castor beans, and many others.[16]

History of the scientific name

.jpg)

The relationship between alpacas and vicuñas was disputed for many years. In the 18th and 19th centuries, the four South American lamoid species were assigned scientific names. At that time, the alpaca was assumed to be descended from the llama, ignoring similarities in size, fleece and dentition between the alpaca and the vicuña. Classification was complicated by the fact that all four species of South American camelid can interbreed and produce fertile offspring.[17] The advent of DNA technology made a more accurate classification possible.

In 2001, the alpaca genus classification changed from Lama pacos to Vicugna pacos, following the presentation of a paper[4] on work by Dr. Jane Wheeler et al. on alpaca DNA to the Royal Society showing the alpaca is descended from the vicuña, not the guanaco.

Fiber

Alpaca fleece is a lustrous and silky natural fiber. While similar to sheep’s wool, it is warmer, not prickly, and bears no lanolin, which makes it hypoallergenic.[18][19] Without lanolin, it does not repel water. It is also soft and luxurious. In physical structure, alpaca fiber is somewhat akin to hair, being very glossy.[2] The preparing, carding, spinning, weaving and finishing process of alpaca is very similar to the process used for wool. Alpaca fiber is also flame-resistant, and meets the US Consumer Product Safety Commission's standards.[20]

Alpacas are typically sheared once per year in the spring. Each shearing produces approximately five to ten pounds (2.2–4.5 kilograms) of fibre per alpaca. An adult alpaca might produce 50 to 90 ounces (1420–2550 grams) of first-quality fibre as well as 50 to 100 ounces (1420–2840 grams) of second- and third-quality fibre.

Prices

The price for American alpacas can range from US$50 for a castrated male (gelding) to US$500,000 for the highest of champions in the world, depending on breeding history, sex, and color.[21] According to an academic study,[22] though, the higher prices sought for alpaca breeding stock are largely speculative and not supported by market fundamentals, given the low inherent returns per head from the main end product, alpaca fiber, and prices into the $100s per head rather than $10,000s would be required for a commercially viable fiber production herd.[23] Breeding stock prices in Australia have fallen from A$10,000–30,000 head in 1997 to an average of A$3,000–4,000 today.

It is possible to raise up to 25 alpacas per hectare (10 alpacas per acre),[24] as they have a designated area for waste products and keep their eating area away from their waste area. However, this ratio differs from country to country and is highly dependent on the quality of pasture available (in many desert locations it is generally only possible to run one to three animals per acre due to lack of suitable vegetation). Fiber quality is the primary variant in the price achieved for alpaca wool; in Australia, it is common to classify the fiber by the thickness of the individual hairs and by the amount of vegetable matter contained in the supplied shearings.

Livestock

Alpacas need to eat 1–2% of body weight per day, so about two 60 lb (27 kg) bales of grass hay per month per animal. When formulating a proper diet for alpacas, water and hay analysis should be performed to determine the proper vitamin and mineral supplementation program. Two options are to provide free choice salt/mineral powder, or feed a specially formulated ration. Indigenous to the highest regions of the Andes, this harsh environment has created an extremely hardy animal, so only minimal housing and predator fencing are needed.[25] The alpaca’s three-chambered stomachs allow for extremely efficient digestion. There are no viable seeds in the manure, because alpacas prefer to only eat tender plant leaves, and will not consume thick plant stems; therefore, alpaca manure does not need composting to enrich pastures or ornamental landscaping. Nail and teeth trimming is needed every six to twelve months, along with annual shearing.

Similar to ruminants, such as cattle and sheep, alpacas have only lower teeth at the front of their mouths; therefore, they do not pull grass up by the roots. Rotating pastures is still important, though, as alpacas have a tendency to regraze an area repeatedly. Alpacas are fiber-producing animals; they do not need to be slaughtered to reap their product, and their fiber is a renewable resource that grows yearly.

See also

References

- ↑ "Harvesting of textile animal fibres". UN Food and Agriculture Organization.

- 1 2 3

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Alpaca". Encyclopædia Britannica. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 721–722.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Alpaca". Encyclopædia Britannica. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 721–722. - ↑ Berrin, Katherine & Larco Museum. The Spirit of Ancient Peru:Treasures from the Museo Arqueológico Rafael Larco Herrera. New York: Thames and Hudson, 1997.

- 1 2 Wheeler, Dr Jane; Miranda Kadwell; Matilde Fernandez; Helen F. Stanley; Ricardo Baldi; Raul Rosadio; Michael W. Bruford (December 2001). "Genetic analysis reveals the wild ancestors of the llama and the alpaca". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 268 (1485): 2575–2584. PMC 1088918

. PMID 11749713. doi:10.1098/rspb.2001.1774. 0962-8452 (Paper) 1471-2954 (Online).

. PMID 11749713. doi:10.1098/rspb.2001.1774. 0962-8452 (Paper) 1471-2954 (Online). - ↑ "Microchips to guard Peruvian Alpacas". BBC News. 30 March 2005.

- ↑ "Harvard students seek meaty profits from alpaca". China Daily. 24 December 2014.

- ↑ Franklin, W. L; Powell, K, J (July 1994). Guard Llamas: A part of integrated sheep protection. Iowa State University. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

- ↑ Chen, B.X.; Yuen, Z.X. & Pan, G.W. (1985). "Semen-induced ovulation in the bactrian camel (Camelus bactrianus)." (PDF). J. Reprod. Fert. 74 (2): 335–339. Retrieved September 12, 2014.

- ↑ ABRI, UNE, Armidale, Australia. "AAA Animal Enquiry". abri.une.edu.au.

- ↑ LaLonde, Judy. "Alpaca Reproduction". Big Meadow Creek Alpacas. Retrieved 23 October 2014.

- ↑ "Breeding and Birthing". Northwest Alpacas. Retrieved 23 October 2014.

- ↑ "Alpacas 101". Parris Hill Farms. Retrieved 23 October 2014.

- ↑ World's Premier Alpaca Resource and Marketplace I love alpacas and I love alpaca.com - Alpacas for Sale 1 866 ALPACAS. Alpaca.com. Retrieved on 2013-07-19.

- ↑ "Retrieved 18 May 2010".

- ↑ Alpaca digestive system. Owning-alpaca.com (2013-03-06). Retrieved on 2013-07-19.

- ↑ "Plants that are poisonous to alpacas".

- ↑ Wheeler, Jane C. (2012). "South American camelids – past, present and future" (PDF). Journal of Camelid Science. 5: 13. Retrieved 25 February 2016.

- ↑ Quiggle, Charlotte. "Alpaca: An Ancient Luxury." Interweave Knits Fall 2000: 74-76.

- ↑ Stoller, Debbie, Stitch 'N Bitch Crochet, New York: Workman, 2006, p. 18.

- ↑ "Error 404". www.alpacainfo.com.

- ↑ "Snowmass Alpaca Sale 2006" (PDF). 25 February 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 March 2006. Retrieved 2007-02-06.

- ↑ Tina L. Saitone; Richard J. Sexton (2005). "Alpaca Lies? Do Alpacas Represent the Latest Speculative Bubble in Agriculture?" (PDF). University of California, Davis. Retrieved 29 June 2010.

- ↑ Alpacas: A handbook for Farmers and Investors; Tuckwell RIRDC 1997

- ↑ "FAQs - Sugarloaf Alpaca Company - Adamstown, MD". www.sugarloafalpacas.com.

- ↑ "Error 404". www.alpacainfo.com.

External links

| Wikispecies has information related to: Lama pacos |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Alpaca. |