Vendée Globe

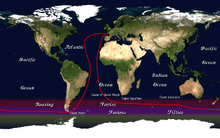

The route of the Vendée Globe race | |

| Founded | 1989 |

|---|---|

| Classes | IMOCA 60 |

| Start | Les Sables-d'Olonne |

| Finish | Les Sables-d'Olonne |

| Type | single-handed non-stop round-the-world race |

| Most recent champion(s) |

Banque Populaire VIII Armel Le Cléac'h |

| Most titles | Michel Desjoyeaux (2) |

| Official website | http://www.vendeeglobe.org/en/ |

The Vendée Globe is a round-the-world single-handed (solo) yacht race, sailed non-stop and without assistance.[1][2] The race was founded by Philippe Jeantot in 1989,[3] and since 1992 has taken place every four years. It is named after the Département of Vendée, in France, where the race starts and ends. The 2016–2017 race started on Sunday, 6 November 2016.[4]

The Vendée Globe is unique in its requirements for its round-the-world run, e.g., contrasting with the likewise single-handed Velux 5 Oceans Race, which is instead sailed in stages (i.e., in legs, with stopovers).[5] The Vendée Globe is considered by many a test of extreme individual endurance, and as the ultimate in ocean racing.[6][7]

The race

History

The race was founded as the "Vendée Globe Challenge" in 1989 by French yachtsman Philippe Jeantot.[8] Jeantot had competed in the BOC Challenge (now the Velux 5 Oceans Race) in 1982–83 and 1986–87, winning both times.[8] Dissatisfied with the race's format, he decided to set up a new round-the-world non-stop race, which he felt would be the ultimate challenge for single-handed sailors.[9]

The first race was run in 1989–90, and was won by Titouan Lamazou; Jeantot himself took part, and placed fourth.[10] The next race was in 1992–93; and it has since then been run every four years.

Yachts

The race is open to monohull yachts conforming to the Open 60 class criteria. Prior to 2004, the race was also open to Open 50 boats. The Open classes are unrestricted in certain aspects, but a box rule governs parameters such as overall length, draught, appendages and stability, as well as numerous other safety features.

Course

The race starts and finishes in Les Sables-d'Olonne, in the Département of Vendée, in France; both Les Sables d’Olonne and the Vendée Conseil Général are official race sponsors.[11] The course is essentially a circumnavigation along the clipper route: from Les Sables d’Olonne, down the Atlantic Ocean to the Cape of Good Hope; then clockwise around Antarctica, keeping Cape Leeuwin and Cape Horn to port; then back to Les Sables d’Olonne.[12] The race generally runs from November to February, and is timed to place the competitors in the Southern Ocean during the austral summer.

Additional waypoints may be set in the sailing instructions for a particular race, in order to ensure safety relative to ice conditions, weather, etc.[13]

The competitors may stop at anchor, but may not draw alongside a quay or another vessel; they may receive no outside assistance, including customised weather or routing information. The only exception is that a competitor who has an early problem may return to the start for repairs and then restart the race, as long the restart is within 10 days of the official start.

The race presents significant challenges; most notably the severe wind and wave conditions in the Southern Ocean, the long unassisted duration of the race, and the fact that the course takes competitors far from the reach of any normal emergency response. A significant proportion of the entrants usually retire, and in the 1996–97 race Canadian Gerry Roufs was lost at sea.[14]

To mitigate the risks, competitors are required to undergo medical and survival courses. They must also be able to demonstrate prior racing experience; either a completed single-handed trans-oceanic race or the completion of a previous Vendée Globe. The qualifying race must have been completed on the same boat as the one the sailor will race in the Vendée Globe; or the competitor must complete an additional trans-oceanic observation passage, of not less than 2,500 miles (4,000 km), at an average speed of at least 7 knots (13 km/h), with his or her boat.

Previous results

1989–1990

The inaugural race was led from early on by the eventual winner, Titouan Lamazou, on Ecureuil d'Aquitaine II.[15] Philippe Jeantot, the race's founder, had problems with breakdowns, and then unfavourable winds, which held him back from the race lead. Philippe Poupon's ketch Fleury Michon X capsized in the Southern Ocean; and Poupon was rescued by Loïck Peyron, who finally finished second, in what was generally a successful first run of the race.[16]

Table: Order of Finish, 1989-1990 Vendée Globe[10]

| Sailor | Yacht | Time |

|---|---|---|

| Ecureuil d'Aquitaine II | 109d 08h 48' 50" | |

| Lada Poch | 110d 01h 18' 06" | |

| 36.15 MET | 112d 01h 14' 00" | |

| Crédit Agricole IV | 113d 23h 47' 47" | |

| TBS-Charente Maritime | 114d 21h 09' 06" | |

| Generali Concorde | 132d 13h 01' 48" | |

| Cacharel | 163d 01h 19' 20" | |

| Did not finish | ||

| Le Nouvel Observateur | damaged auto-pilot (Falklands) | |

| Duracell | received help (New Zealand) | |

| Grinaker | damaged rudder | |

| UAP | dismasted | |

| Fleury Michon X | capsized | |

| O-Kay | toothache | |

1992–1993

The second race attracted a great deal of media coverage. American Mike Plant, one of the entrants in the first Vendée race, was lost at sea on the way to the race, his boat found capsized near the Azores.[17]

The race set off into extremely bad weather in the Bay of Biscay, and several racers returned to the start to make repairs before setting off again (the only stopover allowed by the rules). Four days after the start, British sailor Nigel Burgess was found drowned off Cape Finisterre, having presumably fallen overboard. Alain Gautier and Bertrand de Broc led the race down the Atlantic; however, keel problems forced de Broc to abandon in New Zealand. Gautier continued with Philippe Poupon close behind, but a dismasting close to the finish held Poupon back, allowing Jean-Luc Van Den Heede to take second place.[18]

Table: Order of Finish, 1992-1993 Vendée Globe[19]

| Sailor | Yacht | Time |

|---|---|---|

| Bagages Superior | 110d 02h 22' 35" | |

| Groupe Sofap-Helvim | 116d 15h 01' 11" | |

| Fleury-Michon X | 117d 03h 34' 24" | |

| Cacolac d'Aquitaine | 125d 02h 42' 24" | |

| K&H Banque Matav | 128d 16h 05' 04" | |

| Euskadi Europ 93 BBK | 134d 05h 04' 00" | |

| PRB / Solo Nantes | 153d 05h 14' 00" | |

| Did not finish | ||

| Vuarnet Watches | rigging problems | |

| Everlast / Neil Pryde Sails | lost rudder | |

| Groupe LG | keel problems | |

| Cardiff Discovery | medical reasons | |

| Fujicolor III | sail failure | |

| Maître Coq / Le Monde | unprepared[20] | |

| Nigel Burgess Yachts | lost at sea | |

| Did not start | ||

| Coyote | lost at sea prior to departure[17] | |

1996–1997

Another heavy-weather start in the Bay of Biscay knocked Nándor Fa and Didier Munduteguy out of the race early, and several others returned to the start for repairs before continuing. The rest of the fleet raced to the Southern Ocean, where a second attrition began: Yves Parlier and Isabelle Autissier broke rudders, leaving Christophe Auguin to lead the way into the south.

Heavy weather took a serious toll on the sailors in the far Southern Ocean. Raphaël Dinelli's boat capsized, and he was rescued by Pete Goss.[21] Then, within a few hours of one another, two other boats capsized, with both rescues performed by Australian rescue teams. Finally, contact was lost with Canadian sailor Gerry Roufs; his body was never found, but his boat was found five months later off the Chilean Coast.[14]

The race was won by Christophe Auguin.[22] Catherine Chabaud, sixth and last, was the first woman to finish the race.[23]

Pete Goss was later awarded the Légion d'honneur for his rescue of Dinelli.[21] The capsize of several boats in this race prompted tightening up of the safety rules for entrants, particularly regarding boat safety and stability.[24]

The book Godforsaken Sea by Derek Lundy profiles the 1996–1997 running of the race.[25]

Table: Order of Finish, 1996-1997 Vendée Globe[26]

| Sailor | Yacht | Time |

|---|---|---|

| Geodis | 105d 20h 31' (new record) | |

| Crédit Immobilier | 113d 08h 26' | |

| Groupe LG-Traitmat | 114d 16h 43' | |

| Café Legal-Le Goût | 116d 16h 43' | |

| Aqua Quorum | 126d 21h 25' | |

| Whirlpool-Europe 2 | 140d 04h 38' | |

| Did not finish | ||

| PRB | broken rudder | |

| Aquitaine Innovations | broken rudder | |

| Pommes Rhône Alpes | capsized | |

| Exide Challenger | capsized | |

| Amnesty International | capsized | |

| Budapest | collision | |

| Club 60è Sud | dismasted | |

| Algimouss | capsized | |

| Afibel | beached | |

| Groupe LG2 | lost at sea[14] | |

2000–2001

This race was the first major test of the new safety rules, introduced following the tragedies the previous races. Overall, it was a success; although some boats were again forced to retire from the race, none were lost. This race also featured the youngest entrant ever; Ellen MacArthur, who at 24 years old managed to put together a serious campaign with her custom-built boat Kingfisher.[27]

Yves Parlier was the first to establish a lead, and headlines were made by Dominique Wavre of Switzerland on 10 December 2000 when his 430 nautical miles broke the 24-hour record for distance sailed single-handed.[27] Parlier was soon under attack by Michel Desjoyeaux, who then moved into the lead.[27] Parlier dismasted while pushing to catch up and lost contact with race organizers, resulting in MacArthur's being diverted to provide assistance.[27] MacArthur resumed racing when contact with Parlier was restored, and managed to maintain fourth place.[27]

Desjoyeaux extended his lead to 600 miles (970 km) by Cape Horn, and MacArthur had closed steadily, moving up to second place.[27] By the mid-Atlantic she had caught up, and while negotiating the calms and variable winds of the Doldrums, the two traded the lead position several times.[27]

MacArthur's chance to win was lost when she struck a semi-submerged container and was forced to make repairs.[27] Desjoyeaux and PRB, flying the French flag, would go on to win the race at 93d 3h 57', with MacArthur and Kingfisher under the flag of Great Britain finishing second at 94d 4h 25', and Roland Jourdain and Sill Matines La potagère, also under French flag, finishing third at 96d 1h 2'. MacArthur pulled in to a rapturous reception, as "the youngest ever competitor to finish, the fastest woman around the planet—and only the second solo sailor to get around the globe in less than 100 days."[27] Parlier, meanwhile, had anchored off New Zealand, and managed to fabricate by himself a new carbon-fibre mast from his broken one, and continuing racing, gained an official place.[28][29]

Table: Order of Finish, 2000–2001 Vendée Globe[30]

| Sailor | Yacht | Time |

|---|---|---|

| PRB | 93d 3h 57' (new record) | |

| Kingfisher | 94d 4h 25' | |

| Sill Matines La potagère | 96d 1h 2' | |

| Active Wear | 102d 20h 37' | |

| Union bancaire Privée | 105d 2h 45' | |

| Sodébo | 105d 7h 24' | |

| Team Group 4 | 110d 16h 22' | |

| Voilà.fr | 111d 16h 7' | |

| Gartmore | 111d 19h 48' | |

| Chocolats du Monde | 115d 16h 46' | |

| VM Matériaux | 116d 0h 32' | |

| Aquarelle.com | 121d 1h 28' | |

| Aquitaine Innovations | 126d 23h 36 | |

| DDP / 60e Sud | 135d 15h 17' | |

| Wind Telecommunicazioni | 158d 2h 37' | |

| Did not finish | ||

| Whirlpool | dismasted | |

| Solidaires | electronic problems | |

| Sogal Extenso | damaged rudder | |

| Modern Univ./Humanities | retired | |

| Old Spice | retired | |

| Euroka Services | damaged rudder | |

| This Time – Argos – Help For Autistic Children | rig damage | |

| Armor-Lux/foies Gras | steering problem | |

| Libre Belgique | beached | |

2004–2005

The start of the 2004 race was watched by an estimated 300,000 people, which took place in mild weather. A fast start was followed by a few minor equipment problems, allowing the first racers to cross the equator just after 10 days. This was three days faster than the previous race, with all of the starters still sailing.

Attrition began on entry into the Roaring Forties: Alex Thomson diverted to Cape Town to make unassisted repairs and continue racing. The fleet encountered a number of other problems. Hervé Laurent retired with serious rudder problems, Thomson abandoned, and Conrad Humphreys anchored to make unassisted rudder repairs. Gear problems and abandonments continued, then the fleet ran into an area of ice, and Sébastien Josse hit an iceberg head-on.[31]

The lead changed several times as the fleet re-entered the Atlantic. The race remained close right to the finish, which saw three boats finish within 29 hours.[32]

Table: Order of Finish, 2004–2005 Vendée Globe[33]

| Sailor | Yacht | Time |

|---|---|---|

| PRB | 87d 10h 47' 55" (new record) | |

| Bonduelle | 87d 17h 20' 8" | |

| Ecover | 88d 15h 15' 13" | |

| Temenos | 92d 17h 13' 20" | |

| VMI | 93d 0h 2' 10" | |

| Virbac-Paprec | 98d 3h 49' 38" | |

| Hellomoto | 104d 14h 32' 24" | |

| Arcelor Dunkerque | 104d 23h 2' 45" | |

| Ocean Planet | 109d 19h 58' 57" | |

| Max Havelaar / Best Western | 116d 1h 6' 54" | |

| ROXY | 119d 5h 28' 40" | |

| AKENA Vérandas | 125d 4h 7' 14" | |

| Benefic | 126d 8h 2' 20" | |

| Did not finish | ||

| Pro-Form | technical problems | |

| Sill Véolia | keel problems | |

| Hugo Boss | hole in the deck | |

| VM Matériaux | broken boom | |

| Skandia | lost the keel | |

| UUDS | rudder problem | |

| Brother | keel problems | |

2008–2009

The 2008 Vendée Globe began on 9 November 2008. The problems encountered by Jean Le Cam—losing his keel bulb and capsizing in the Southern Ocean—had a major impact on the order of finish. Vincent Riou diverted and found his boat, circling to try and toss a rope to Le Cam who had exited a security hatch to hang onto the rudder. After three failed attempts, Riou went in closer, managing to rescue Le Cam but also damaging his mast. Riou retired, but was awarded third place on redress, as he was third when diverted to assist the boat in distress.[34]

The 2008 Vendée Globe was won by Michel Desjoyaux, who set a new record at 84d 3h 9' 8".[35]

Table: Order of Finish, 2008–2009 Vendée Globe[36]

| Sailor | Yacht | Time |

|---|---|---|

| Foncia | 84d 3h 9' 8" (new record) | |

| Brit Air | 89d 9h 39' 35" | |

| Safran | 95d 3h 19' 36" | |

| Roxy | 95d 4h 39' 1" | |

| Bahrain Team Pindar | 98d 20h 29' 55" | |

| Aviva | 99d 1h 10' 57" | |

| Akena Verandas | 105d 2h 33' 50" | |

| Toe In The Water | 109d 0h 36' 55" | |

| Great American III | 121d 0h 41' 19" | |

| Fondation Ocean Vital | 125d 2h 32' 24" | |

| Nauticsport-Kapsch | 126d 5h 31' 56" | |

| Did not finish | ||

| PRB | day 59: dismasted. Redress Given: 3rd place | |

| Veolia Environnement | day 85: lost keel | |

| VM Matériaux | day 58: lost keel bulb, capsized | |

| Artemis | day 56: delaminated mainsail | |

| Paprec-Virbac 2 | day 53: lost port rudder | |

| Algimouss Spirit of Canada | day 50: broken spreaders | |

| BT | day 50: broken rudder system | |

| Generali | day 40: fractured femur | |

| Ecover 3 | day 38: dismasted | |

| Groupe Maisonneuve | day 37: faulty halyards, broken auto-pilot | |

| Gitana Eighty | day 36: dismasted | |

| Cheminées Poujoulat | day 36: ran aground | |

| Temenos | day 35: damaged keel box | |

| Pakea Bizkaia | day 28: faulty starboard rudder box | |

| Delta Dore | day 17: damaged rig | |

| Hugo Boss | day 6: cracked hull | |

| Energies Autour du Monde | day 4: dismasted | |

| DCNS | day 4: dismasted | |

| Groupe Bel | day 4: dismasted | |

2012–2013

The 2012 Vendée Globe started on 10 November 2012. The race saw the 24-hour singlehanded distance record repeatedly reset by several competitors. Armel Le Cléac’h (Banque Populaire) set a new race record for shortest time to the longitude of the Cape of Good Hope,[37] and François Gabart (Macif) set new race records for shortest time to the longitude of Cape Leeuwin in Australia and to Cape Horn. On 27 January 2013, Gabart set a new Vendée Globe record with just over 78 days to complete the circumnavigation. The interval of 3h 17’ between the arrivals of the first and second contenders is also the shortest in the race's history.[38]

Table: Order of Finish, 2012–2013 Vendée Globe[39]

| Sailor | Yacht | Time |

|---|---|---|

| Macif | 78d 2h 16' 40" (new record) | |

| Banque Populaire | 78d 5h 33' 52" | |

| Hugo Boss | 80d 19h 23' 43" | |

| Virbac-Paprec 3 | 86d 3h 3' 40" | |

| SynerCiel | 88d 0h 12’ 58" | |

| Gamesa | 88d 6h 36' 26" | |

| Mirabaud | 90d 3h 14' 42" | |

| Akena Vérandas | 91d 2h 09' 02" | |

| Votre Nom autour du Monde avec EDM Projets | 92d 17h 10' 14" (incl. 12h time penalty for unsealing and using emergency water supply) | |

| initiatives cœur | 98d 21h 56' 10" | |

| Team Plastique | 104d 02h 34' 30" | |

| Did not finish | ||

| Acciona 100% EcoPowered | day 84: capsized | |

| Cheminées Poujoulat | day 51: disqualified after receiving assistance, however he completed the course in 88d 10h 27' 50" | |

| PRB | day 14: broken outrigger stay resulting from collision | |

| Energa | day 11: electrical issues resulting in autopilot not being able to work | |

| Maître CoQ | day 9: broken keel ram | |

| Savéol | day 5: dismasted | |

| Bureau Vallée | day 3: collision | |

| Groupe Bel | day 2: collision | |

| Safran | day 1: damaged keel | |

2016–2017

.jpg)

The 2016 - 17 race started from Les Sables d'Olonne on November 6, 2016; it was the eighth competition, with 29 skippers from ten countries.[40] It lasted 124.5 days while going around the three great capes - the Cape of Good Hope (South Africa), Cape Leeuwin (Australia) and Cape Horn (Chile) and saw a record 18 skippers make it to the finish line.[41]

This edition of the race was the first to feature foiling monohull boats equipped with hydrofoils and was therefore closely watched to evaluate the durability of foils in such circumstances.[42] Of note, the four foiling boats sailed by professional skippers that made it to the finish line took the top places indicating that such appendices are likely to be adopted by other sailors (see table below). The winner of this edition was Armel Le Cléac'h, finishing on January 19, 2017 in a record breaking time of 74 days, three hours and 35 minutes.[43] Other records were set during the course, including the greatest distance covered by a monohull over the course of 24h,[44][45] the fastest southbound crossing of the Equator[46] and Cape of Good Hope[47] by Alex Thomson. Winner Armel le Cleac'h also broke the record for the fastest crossing of Cape Leeuwin,[48] Cape Horn[49] and the Equator (northbound).[50]

The race featured the youngest and oldest skippers ever to complete the race - on consecutive days (Alan Roura, 23 years old; Rich Wilson, aged 66). Also, Didac Costa was forced to return to harbour after less than one hour of sailing as a result of water damage to the boat's electric system. He returned to the race four days later and finished in 14th place.[51] In addition, Conrad Colman finished under jury rig after dismasting 715 nm from the finish, while running short on food and electric power. The latter was compounded by the fact that his boat - Foresight Natural Energy - was propelled solely by renewable energy sources and the critical speed required for using hydrogenerators as well as sunlight to feed his solar panels were short of par. Colman was the first skipper to complete the Vendée Globe without using fossil fuels, two weeks after breaking his mast.[52]

Table: Registrants, 2016–2017 Vendée Globe[53]

| Sailor | Yacht | Launch Date/Designer | Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| Banque Populaire VIII § | Jun 2015/VPLP-Verdier | 74d 03h 35' 46" (current record) [54] | |

| Hugo Boss § | Sep 2015/VPLP-Verdier | 74d 19h 35' 15" [55] | |

| Maître CoQ § | Sep 2010/VPLP-Verdier | 78d 06h 38' 40" [56] | |

| StMichel-Virbac § | Sep 2015/VPLP-Verdier | 80d 01h 45' 45" [57] | |

| Quéguiner - Leucémie Espoir | Aug 2007/VPLP-Verdier | 80d 03h 11' 09" [58] | |

| Finistère Mer Vent | Jan 2007/Farr | 80d 04h 41' 54" [59] | |

| Bureau Vallée | Sep 2006/Farr | 87d 19h 45' 49" [60] | |

| Spirit Of Hungary | Apr 2014/Nándor Fa & Attila Déry | 93d 22h 52' 09" [61] | |

| Comme un Seul Homme | May 2008/Finot-Conq | 99d 04h 56' 20" [62] | |

| La Mie Câline | Feb 2007/Farr | 102d 20h 24' 09" [63] | |

| Newrest - Matmut | Jul 2007/Farr | 103d 21h 01' 00" [64] | |

| La Fabrique | Jul 2000/Pierre Rolland | 105d 20h 10' 32" [65] | |

| Great American IV | Sep 2006/Owen Clarke | 107d 00h 48' 18" [66] | |

| One Planet One Ocean | Jan 2000/Owen Clarke | 108d 19h 50' 45" [67] | |

| Famille Mary - Etamine Du Lys | Jan 1998/Marc Lombard | 109d 22h 04' 00" [68] | |

| Foresight Natural Energy | Jan 2005/Lavranos-Artech | 110d 01h 58' 41" [52] | |

| No Way Back § | Aug 2015/VPLP-Verdier | 116d 09h 24' 12" [69] | |

| TechnoFirst - FaceOcean | Jan 1998/Finot | 124d 12h 38' 18" [70] | |

| Did not finish | |||

| Kilcullen Voyager - Team Ireland | Aug 2007/Owen Clarke & Clay Oliver | day 56: Dismasted 180 nm SE of New Zealand [71] | |

| SMA | Jan 2011/VPLP-Verdier | day 49: Hydraulic-keel fissured [72] | |

| Le Souffle Du Nord Pour Le Projet Imagine | Jan 2007/VPLP-Verdier | day 44: Damaged hull due to collision with an UFO [73] | |

| Compagnie Du Lit - Boulogne Billancourt | Jan 2007/Finot-Conq | day 41: Dismasted 950 nautical miles away from Australia [74] | |

| Edmond De Rothschild § | Aug 2015/VPLP-Verdier | day 30: Damage port foil - South of Australia [75] | |

| Bastide Otio | May 2010/VPLP-Verdier | day 30: Damaged keel - North of Crozet Islands [76] | |

| Spirit Of Yukoh | Jan 2007/Farr | day 27: Damaged masthead - South of Cape of Good Hope [77] | |

| Initiatives-Cœur | Sep 2006/Farr | day 23: Damaged masthead - North of Cape Verde Islands [78] | |

| Safran § | Mar 2015/VPLP-Verdier | day 19: Damaged rudder - South Atlantic [79] | |

| PRB | Mar 2010/VPLP-Verdier | day 17: Damaged keel - South Atlantic [80] | |

| MACSF | Jul 2007/Finot-Conq | day 14: Damaged keel [81] | |

§ - boat equipped with hydrofoils

.jpg)

Edmond de Rotschild, a new foiling yacht that took part in the race .jpg)

Banque populaire VIII, Armel Le Cléac'h's boat, departure day .jpg)

Hugo Boss, Alex Thomson's boat, departure day

Port foil on Hugo Boss, Alex Thomson's boat

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Vendée Globe. |

External links

References

- ↑ SSN Staff (13 November 2016). "Vendée Globe: Thomson Leads into the Doldrums". Scuttlebutt Sailing News. Retrieved 13 November 2016.

- ↑ VendéeGlobe.org Staff (13 November 2016). "Home Page, Vendée Globe 2016-2017 [race]". vendeeglobe.org. Retrieved 13 November 2016.

- ↑ BBC Staff (27 January 2013). "Vendee Globe 2012-13: Francois Gabart Breaks Solo Record [BBC Sport: Sailing]". Retrieved 13 November 2016.

- ↑ Boyd, James (9 December 2014). "30 Skippers for the Next Vendée Globe?". The Daily Sail. Retrieved 13 November 2016.

- ↑ Velux 5 Oceans Media (15 October 2010). "Velux 5 Oceans- The Race in Context - 28 Years of History and Drama". Sail World. Retrieved 13 November 2016.

What is now known as the Velux 5 Oceans Race, the singlehanded around the world race with stopovers has been sailed for almost 30 years… The race was split into four legs, with stops in Cape Town, Sydney and Rio de Janeiro before finishing in back in Newport.

- ↑ Museler, Chris (9 November 2008). "Racers in Vendée Globe Start Nonstop Solo Quest". New York Times. Retrieved 8 December 2008.

Compared with other global ocean races […] the Vendée Globe is considered the most extreme sailing event in the world

- ↑ "Vendée Globe: Sailing's Everest". The Independent. 11 November 2008. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- 1 2 The Museum of Yachting (14 November 2016) [1990]. "Philippe Jeantot, 1952-". The Single-Handed Sailors' Hall of Fame. Newport, RI: The Museum of Yachting. Retrieved 14 November 2016 – via Windlass Creative [Sally Anne Santos].

[Quote:] Inducted to Single-Handed Sailors' Hall of Fame, 1990.

- ↑ "Introduction". Vendée Globe. Archived from the original on 15 May 2008. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- 1 2 "Edition 1989/1990 : Une grande course est née". Vendée Globe (in French). Archived from the original on 22 October 2004. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ↑ VendéeGlobe.org Staff (13 November 2016). "Partners - Vendée Globe 2016-2017". vendeeglobe.org. Retrieved 13 November 2016.

- ↑ Nielsen, Peter (11 May 2016). "Inside the Vendée Globe". Sail Magazine. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ↑ Laven, Kate (3 December 2012). "Vendee Globe 2012-13: Dicing with ice as fleet heads into desolate Southern Ocean". The Telegraph. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- 1 2 3 Evans, Jeremy (1 April 2008). Sailing. Dorling Kindersley Ltd. p. 317. ISBN 9781405334723.

Tragically, another life was lost as French Canadian Gerry Roufs was lost at sea

- ↑ "Yachting's 1990 Honor Roll". Yachting. 170 (4). April 1991. ISSN 0043-9940. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ↑ Byrne, Dan (27 January 1990). "'Roaring 40s' Claim 3 Sailboats". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- 1 2 Lloyd, Barbara (26 November 1992). "Solo Sailor Is Presumed To Be Dead". New York Times. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ↑ "French Toast Tough Vendée Globe Fleet". Yachting. 174 (1). July 1993. ISSN 0043-9940. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ↑ "Edition 1992/1993 : L'édition des premiers drames". Vendée Globe (in French). Archived from the original on 22 October 2004. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ↑ Agnus, Christophe; Lautrou, Pierre-Yves (13 October 2004). Le roman du Vendée-Globe (in French). Grasset. ISBN 9782246675990.

- 1 2 "Hero sailor Yachtsman of the Year". BBC. 10 January 1998. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ↑ "Open 60 Class Review". Yachting. 181 (4). April 1997. ISSN 0043-9940. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ↑ "Solo yachtswoman and journalist Catherine Chabaud wins Woman of the Year award". Euronews. 14 May 2015. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ↑ Finot, Jean-Marie (March 1999). "60’ Open, the conditions of safety, past evolution, current state, future". finot.com. Retrieved 9 December 2016.

- ↑ Lundy, Derek (2000). Godforsaken Sea: The True Story of a Race Through the World's Most Dangerous Waters. New York, NY: Anchor. ISBN 0385720009.

- ↑ "Edition 1996/1997 : Le Globe ne tourne plus rond". Vendée Globe (in French). Archived from the original on 22 October 2004. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 BBC Staff (9 February 2001). "Vendee Globe: The Full Story [BBC Sport: Sailing]". Retrieved 13 November 2016.

- ↑ Clarey, Christopher (16 March 2001). "Despite Mishaps, French Sailor Is Near Finish in Vendee Globe Race: A Battered but Unbowed Arrival". New York Times. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ↑ Martinez, Thierry. "Yves Parlier - Vendée Globe - Exclusive Images". thmartinez.com. Retrieved 9 December 2016.

- ↑ "Edition 2000/2001 : Le Globe Express". Vendée Globe (in French). Archived from the original on 22 October 2004. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ↑ "Not so calm before the storm". The Independent. 2 April 2006. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

[Josse] came 5th in the 2005 Vendée Globe, despite hitting an iceberg.

- ↑ Berlin, Peter (4 February 2005). "Sailing: Around the world (alone) in 87 days". New York Times.

- ↑ "Vendée Globe 2004: Rankings and Positions". Vendée Globe. 14 March 2005. Archived from the original on 18 March 2005. Retrieved 9 December 2016.

- ↑ Agence France-Presse (13 January 2009). "Competitor Wins Appeal". New York Times. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ↑ "Desjoyeaux wins Vendee Globe for second time". New York Times. 1 February 2009. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ↑ "Vendée Globe Ranking". Vendée Globe. Archived from the original on 16 March 2009. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ↑ "Leader Le Cléac’h Breaks Riou’s Record". Vendée Globe. 3 December 2012. Retrieved 9 December 2016.

- ↑ Museler, Chris (1 February 2013). "A Worldwide Race Has a Winner, but Is Not Over". New York Times. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ↑ "Rankings". Vendée Globe. 28 February 2013. Archived from the original on 28 February 2013. Retrieved 9 December 2016.

- ↑ "Vendée Globe Kicks Off With Record-Breaking Goals for Skippers". RFI. 11 November 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ↑ http://www.vendeeglobe.org/en/news/19137/a-look-back-at-the-highlights-of-the-8th-vendee-globe

- ↑ "2016 Vendee Globe". Mainsail. 14 December 2016. CNN International.

- ↑ http://www.vendeeglobe.org/en/news/18251/le-cleac-h-smashes-vendee-globe-race-record-in-spectacular-style

- ↑ http://www.vendeeglobe.org/en/news/18129/alex-thomson-has-smashed-the-24-hour-record

- ↑ https://www.sailspeedrecords.com/24-hour-distance

- ↑ http://www.vendeeglobe.org/en/news/16161/southern-star-new-southbound-race-reference-for-thomson

- ↑ http://www.vendeeglobe.org/en/news/16481/cape-of-good-hope-record-tumbles-as-southern-ocean-beckons

- ↑ http://www.vendeeglobe.org/en/news/16867/leeuwin-record-for-leader-le-cleac-h-damage-for-josse-and-attanasio

- ↑ http://www.vendeeglobe.org/en/news/17449/le-cleac-h-at-the-horn-thomson-in-the-cooler

- ↑ http://www.vendeeglobe.org/en/news/17865/leader-le-cleac-h-back-in-northern-hemisphere

- ↑ http://www.vendeeglobe.org/en/news/19137/a-look-back-at-the-highlights-of-the-8th-vendee-globe

- 1 2 http://www.vendeeglobe.org/en/news/18985/the-crazy-kiwi-conrad-colman-takes-sixteenth-place

- ↑ "Near Record fleet to attempt Everest of the Seas". Scuttlebutt Sailing News. 6 September 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ↑ Véronique Malécot (2017-01-19). "Armel Le Cléac’h remporte son premier Vendée Globe en un temps record". lemonde.fr (in French). Retrieved 2017-01-19.

- ↑ http://www.vendeeglobe.org/en/news/18263/alex-thomson-finishes-second

- ↑ http://www.vendeeglobe.org/en/news/18349/jeremie-beyou-maitre-coq-takes-third-place-in-the-vendee-globe

- ↑ http://www.vendeeglobe.org/en/news/18389/jean-pierre-dick-fourth-in-the-vendee-globe

- ↑ http://www.vendeeglobe.org/en/news/18415/yann-elies-fifth-in-the-vendee-globe

- ↑ http://www.vendeeglobe.org/en/news/18417/jean-le-cam-sixth-in-the-vendee-globe

- ↑ http://www.vendeeglobe.org/en/news/18577/good-luck-good-judgement-good-pace-louis-burton-s-lucky-seventh

- ↑ http://www.vendeeglobe.org/en/news/18669/nandor-fa-spirit-of-hungary-8th-in-the-vendee-globe

- ↑ http://www.vendeeglobe.org/en/news/18795/eric-bellion-9th-in-the-vendee-globe-first-rookie

- ↑ "News - Arnaud Boissières takes tenth place - Vendée Globe 2016-2017". Retrieved 2017-02-17.

- ↑ http://www.vendeeglobe.org/en/news/18873/amedeo-writes-his-own-vendee-globe-story-11th-place

- ↑ http://www.vendeeglobe.org/en/news/18911/alan-roura-takes-twelfth-place

- ↑ http://www.vendeeglobe.org/en/news/18933/rich-wilson-takes-thirteenth-place

- ↑ http://www.vendeeglobe.org/en/news/18959/didac-costa-takes-14th-place

- ↑ http://www.vendeeglobe.org/en/news/18981/romain-attanasio-takes-15th-place

- ↑ http://www.vendeeglobe.org/en/news/19037/dutch-sailor-pieter-heerema-takes-seventeenth-place

- ↑ http://www.vendeeglobe.org/en/news/19103/sebastien-destremau-takes-18th-place-to-bring-the-vendee-globe-to-a-close

- ↑ "Enda O’Coineen’s round the world effort reaches premature end". The Irish Times. 1 January 2017. Retrieved 2 January 2017.

- ↑ "Le skipper Paul Meilhat contraint à l'abandon en raison d'une avarie sur sa coque". L'Équipe (in French). 25 December 2016. Retrieved 2 January 2017.

- ↑ http://www.vendeeglobe.org/en/news/17311/coastguards-on-their-way-to-thomas-ruyant

- ↑ http://www.vendeeglobe.org/en/news/17243/le-diraison-heading-for-melbourne "Le Diraison heading for Melbourne."

- ↑ http://www.vendeeglobe.org/en/news/16927/sebastien-josse-and-the-mono60-edmond-de-rothschild-announce-their-retirement

- ↑ http://www.vendeeglobe.org/en/news/16901/rescue-plan-for-stricken-de-pavant-is-in-operation

- ↑ http://www.vendeeglobe.org/en/news/16811/kojiro-shiraishi-on-spirit-of-yukoh-forced-to-retire

- ↑ http://www.vendeeglobe.org/en/news/16147/thomson-leads-into-southern-hemisphere-de-lamotte-heads-home-but-heartbeat-continues

- ↑ http://www.vendeeglobe.org/en/news/16489/damage-to-safran-morgan-lagraviere-forced-to-retire

- ↑ http://www.vendeeglobe.org/en/news/16409/keel-damage-on-prb-vincent-riou-forced-to-retire

- ↑ http://www.vendeeglobe.org/en/news/16313/bertrand-de-broc-forced-to-retire

Coordinates: 46°29′42″N 1°47′19″W / 46.4951°N 1.7886°W