Long Island Motor Parkway

|

Long Island Motor Parkway | |

|

Remnant of Long Island Motor Parkway c. 2008 at Springfield Boulevard in Queens, looking East | |

| |

| Location | Roughly Alley Pond and Cunningham Parks, between Winchester Blvd. and Clearview Expressway, between 73rd Ave. and Peck Ave., Queens, New York City, New York |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 40°44′13″N 73°45′35″W / 40.73694°N 73.75972°W |

| Area | 10 acres (4.0 ha) |

| Built | 1908 |

| Architect | Williams, E.G.; Brown, E.H. |

| NRHP Reference # | 02000301[1] |

| Added to NRHP | April 01, 2002 |

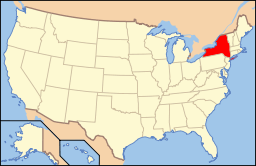

The Long Island Motor Parkway (LIMP), also known as the Vanderbilt Parkway and Motor Parkway, was a parkway on Long Island, New York, in the United States. It was the first roadway designed for automobile use only.[2] The road was privately built by William Kissam Vanderbilt II with overpasses and bridges to remove intersections. It opened in 1908 as a toll road and closed in 1938 when it was taken over by the state of New York in lieu of back taxes. Parts of the parkway survive today in sections of other roadways and as a bicycle trail in Queens.

History

Origins and construction

William Kissam Vanderbilt II, the great-grandson of Cornelius Vanderbilt, was an auto-racing enthusiast and created the Vanderbilt Cup, the first major road racing competition, in 1904. He ran the races on local roads in Nassau County during the first decade of the 20th century, but the deaths of two spectators and injury to many others showed the need to eliminate racing on residential streets. Vanderbilt responded by floating a company to build a graded, banked and grade-separated highway suitable for racing that was also free of the horse manure dust often churned up by motor cars. The resulting Long Island Motor Parkway, with its banked turns, guard rails, reinforced concrete tarmac, and controlled access, was the first limited-access roadway in the world.[3]

The road was originally planned to stretch for 70 miles (110 km) in and out of New York City as far as Riverhead, the county seat of Suffolk County, and point of division for the north and south forks of Long Island. Only 45 miles (72 km) (from Queens in New York City to Lake Ronkonkoma) were constructed, at a cost of $6 million.[3] Construction began in June 1908 (a year after the Bronx River Parkway). On October 10, 1908,[4] a 10-mile-long (16 km) section opened as far as modern Bethpage, making it the first superhighway. It hosted races in 1908 and on the full road in 1909 and 1910, but an accident in the latter year's Vanderbilt Cup, killing two riding mechanics with additional injuries,[5] caused the New York Legislature to ban racing except on race tracks, ending its career as a racing road.

By 1911, the road was extended to Lake Ronkonkoma. It was the first roadway designed exclusively for automobile use, the first concrete highway in the United States, and the first to use overpasses and bridges to eliminate intersections.[6]

Access

It was a toll road, with access at a small number of toll booths, joined to local roads by short connector roads. Traffic could turn left between the parkway and connectors, crossing oncoming traffic, so it was not a freeway. Access points were:

- Nassau Boulevard (NY 25D) west of Francis Lewis Boulevard. The right-of-way of Nassau Boulevard was later used for the Long Island Expressway (I-495).

- Hillside Avenue (NY 25B) – Springfield Boulevard south of 77th Avenue

- Great Neck – Lakeville Road south of Lake Road

- Roslyn – Roslyn Road south of Barnyard Lane

- Mineola – Jericho Turnpike (NY 25) at Rudolph Drive

- Garden City – Clinton Road at Vanderbilt Court

- Meadow Brook – Merrick Avenue north of Stewart Avenue

- Bethpage – Hicksville Road (NY 107) south of Avoca Avenue; Round Swamp Road south of Old Bethpage Road

- Huntington – Broad Hollow Road north of Spagnoli Road

- Deer Park – Deer Park Road (NY 231)

- East Commack – Commack Spur along Harned Road (CR 14) to Jericho Turnpike (NY 25)

- Brentwood – Washington Avenue

- Ronkonkoma – Rosevale Avenue

When the parkway opened, the toll was set at $2. It was reduced to $1.50 in 1912, $1 in 1917, and 40 cents in 1938. The first six toll houses were designed by John Russell Pope, the architect who designed the rotunda in the American Museum of Natural History and the Jefferson Memorial.[3] The toll houses were designed to include living space for the toll collectors so that toll could be collected at all hours. The most prominent remaining toll house is in Garden City.[7] Once located at the junction of Clinton Road and Vanderbilt Court, it was moved in 1989 to 230 Seventh Street, now the headquarters of the Garden City Chamber of Commerce.[8]

Demise and post-demise

Roadway design advances of the 1920s rendered the road obsolete less than 20 years after construction. At the same time Robert Moses was planning the Northern State Parkway. Initially the owners and some Long Island officials wanted the road integrated into the state parkway system, despite its narrow roadway and steep bridges not meeting new standards. Moses was against the idea, stating that the parkway would need significant reconstruction. The completion of the Northern State Parkway signaled the end for the road. In 1938 it was sold to New York State for $80,000 in lieu of back taxes and closed.[3] Most of the road in Queens (west of Winchester Boulevard, whose widening destroyed an overpass) is a bicycle trail from Cunningham Park to Alley Pond Park, part of the Brooklyn–Queens Greenway.

The Nassau County roadway has been developed, or turned into a right of way for Long Island Power Authority transmission lines. Part of the road in Suffolk County is County Route 67 (CR 67) and parts were incorporated into the Meadowbrook State Parkway.[3]

In 2005, two historians / preservationists voiced their intention of preserving undeveloped portions of the road as part of a historical hike/bike trail (minus the existing Queens trail segment), submitting a formal proposal to Nassau County, Suffolk County, the Long Island Power Authority (which uses several portions of the old right-of-way to run powerlines) and the State of New York. Work is expected to begin in the near future, and most of that work will be carried out by the New York State Department of Transportation.

In 2008 the road celebrated its 100th anniversary. On October 30, 2011, a centennial event marked the 100th anniversary of the completion of the Lake Ronkonkoma section. Led by the winner of the 1909 and 1910 Vanderbilt Cup races, a parade of automobiles made prior to 1948 went from Dix Hills to Lake Ronkonkoma.[9]

Remaining portions

| |

|---|---|

| Location: | Huntington–Lake Ronkonkoma |

| Length: | 14.51 mi[10] (23.35 km) |

Most of the road from Queens to western Suffolk County has been obliterated by homes, other roads and structures, or has returned to nature. Some parts can be traced, and some bridges still exist.

The western portion in Queens was reopened a few months after closure as a bicycle path from Cunningham Park to Alley Pond Park. Now part of the Brooklyn–Queens Greenway (BQGW), it starts at Francis Lewis Boulevard in Cunningham Park where a bridge over the Long Island Expressway connects it to a park, formerly called Black Stump Park, which in turn connects Cunningham Park with Kissena Park. There is access to Peck Avenue just east of the start of the bike path.

The Greenway runs south, parallel with 199th Street, and crosses a bridge over 73rd Avenue. It swings east to Francis Lewis Boulevard, crossing it on a bridge. It continues through the park, crossing the Clearview Expressway by a tunnel, and then Hollis Hills Terrace on a fourth bridge before leaving the park. There is access to 209th and 210th Streets in Hollis Hills. It goes through a wooded corridor, soon crossing over Bell Boulevard on a bridge, and provides access to 220th Street just east of Bell Boulevard. After crossing Springfield Boulevard on another bridge, there is access to Cloverdale Boulevard where the main line of BQGW goes north. The road now enters Alley Pond Park, crosses under the Grand Central Parkway, and provides access to Union Turnpike before ending at Union Turnpike and Winchester Boulevard at the park's eastern boundary.

A small section of the roadway remains in the Village of Lake Success in Great Neck, though unmarked and not open to the public. Most of this section is currently within the property of Great Neck South High School.[11] The toll house was not razed but incorporated into the building of a private house.[12]

Another section may be seen on either side of Willis Avenue on the boundary between Albertson and Wiliston Park. On the East side of the avenue, several hundred yards of road provide access to the Williston Park pool property abutting the LIRR. [13]

The road survives as a continuous county road, Vanderbilt Motor Parkway (CR 67), from Half Hollow Road in Dix Hills to its original end in Ronkonkoma, just a few blocks short of the lake. Signage along the way also identifies it variously as Vanderbilt Parkway and Motor Parkway. From Half Hollow Road, it goes northeast to NY 231 (Deer Park Avenue). It starts to parallel the Northern State Parkway and intersects with CR 4 (Commack Road) in Commack. It crosses the Sagtikos State Parkway (with northbound access northbound) and heads south to I-495 (the Long Island Expressway). The parkway heads eastward, paralleling the expressway (with access to and from the LIE) before ultimately crossing it and continuing southeast to NY 111 (Joshua's Path). It then heads north, crossing the LIE again at exit 57, and then curves to the east and crosses NY 454 (Veterans Memorial Highway). It heads east across Old Nichols and Terry roads ahead of one final northeastward turn to end at Rosedale Avenue (CR 93) in Ronkonkoma, close to the lake.

Though not a limited access road since 1938, most of the road was recognizable into the 1970s, while new intersections continued to be cut through it. In the approximate middle of the road in and around Islandia, office construction and other commercial building has widened the road and made it appear a typical highway. Other portions, especially at the western and eastern ends of the surviving road, can be enjoyed for greenery, graded and banked turns, and rolling hills, albeit at considerably less than racecar speeds.

See also

References

- ↑ National Park Service (March 13, 2009). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- ↑ Kroplick, Howard; Al Velocchi (2009). Long Island Motor Parkway, The. Images of America. Charleston, SC: Acadia Publishing. p. 7. ISBN 0-7385-5793-5.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Patton, Phil (October 9, 2008). "A 100-Year-Old Dream: A Road Just for Cars". The New York Times. Retrieved September 16, 2009.

- ↑ "35 cars to race on the Motor Parkway". The New York Times. October 10, 1908. p. 10. Archived from the original on December 13, 2015.

- ↑ "Alco again wins Vanderbilt Cup but race's death toll is high". The New York Times. October 2, 1910. Archived from the original on July 6, 2014.

- ↑ http://www.newsday.com/community/guide/lihistory/ny-history-hs701a,0,6567870.story Archived November 22, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Garden City Historical Society Garden City Toll Lodge

- ↑ Giardino, Carisa (June 23, 2011). "Efforts Underway to Preserve Long Island Motor Parkway". Garden City Patch. Retrieved August 26, 2011.

- ↑ Vaccaro, Chris R. (October 21, 2011). "Motor Parkway Parade Rescheduled for October 30". Sachem Patch. Retrieved 2011-11-25.

- ↑ "Region 3 Inventory Listing". New York State Department of Transportation. March 2, 2009. Archived from the original on April 19, 2014. Retrieved February 4, 2010.

- ↑ ArbitalJacoby, Sheri (August 8, 2014) "Duo Push For Park Path" the Great Neck Record. Retrieved December 23, 2015.

- ↑ The Great Neck Lodge in Lake Success Vanderbiltcupraces.com. Retrieved December 23, 2015.

- ↑ "Long Island Motor Parkway". Forgotten New York. Retrieved 16 April 2017.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Long Island Motor Parkway. |

- Long Island Motor Parkway (VanderbiltCupRaces.com)

- Long Island Vanderbilt Parkway (NYCROADS.com)

- Long Island Motor Parkway Preservation Society (Sam Berliner III)

- Long Island Motor Parkway (Arrt's Arrchives)

- "The Age of the Auto: Sportsman William K. Vanderbilt II's cup race paves the way to the future," by Sylvia Adcock (Newsday—Long Island; Our Story)

- Art's Long Island Motor Parkway Site (Art K.)

- LIMP (wikimapia.org map showing route and remnants of the parkway)

- County Route 67 at Alps' Roads