Valproate

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Convulex, Depakote, Epilim, Stavzor, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682412 |

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of administration | By mouth, intravenous |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | Rapid absorption |

| Protein binding | 80–90%[1] |

| Metabolism | Hepatic—glucuronide conjugation 30–50%, mitochondrial β-oxidation over 40% |

| Biological half-life | 9–16 hours[1] |

| Excretion | Urine (30-50%)[1] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

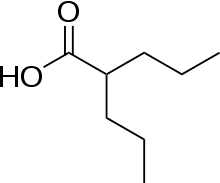

| Synonyms | 2-Propylvaleric acid |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| NIAID ChemDB | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.002.525 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C8H16O2 |

| Molar mass | 144.211 g/mol |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Valproate (VPA), and its valproic acid, sodium valproate, and divalproex sodium forms, are medications primarily used to treat epilepsy and bipolar disorder and to prevent migraine headaches.[2] It is useful for the prevention of seizures in those with absence seizures, partial seizures, and generalized seizures.[2] It can be given intravenously or by mouth.[2] Long and short acting formulation of tablets exist.[2]

Common side effects include nausea, vomiting, sleepiness, and a dry mouth.[2] Serious side effects can include liver problems and regular monitoring of liver function tests is therefore recommended.[2] Other serious risks include pancreatitis and an increased suicide risk.[2] It is known to cause serious abnormalities in the baby if taken during pregnancy.[2] Because of this it is not typically recommended in women of childbearing age who have migraines.[2]

It is unclear exactly how valproate works.[2][3] Proposed mechanisms include affecting GABA levels, blocking voltage-gated sodium channels, and inhibiting histone deacetylases.[4][5] Valproic acid is a branched short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) made from valeric acid.[4]

Valproate was first made in 1881 and it came into medical use in 1962.[6] Valproate is included in the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines, the most effective and safe medicines needed in a health system.[7] It is available as a generic medication.[2] The wholesale cost in the developing world is between 0.14 and 0.52 USD per day.[8] In the United States, it costs roughly $0.90 USD per day.[2] It is marketed under the brand name Depakote among others.[2]

Terminology

Valproic acid (VPA) is an organic weak acid. The conjugate base is valproate. The sodium salt of the acid is sodium valproate and a coordination complex of the two is known as divalproex sodium.

Medical uses

It is used primarily to treat epilepsy and bipolar disorder. It is also used to prevent migraine headaches.[9]

Epilepsy

Valproate has a broad spectrum of anticonvulsant activity, although it is primarily used as a first-line treatment for tonic-clonic seizures, absence seizures and myoclonic seizures and as a second-line treatment for partial seizures and infantile spasms.[9][10] It has also been successfully given intravenously to treat status epilepticus.[11][12]

Mental illness

Bipolar disorder

Valproate products are also used to treat manic or mixed episodes of bipolar disorder.[13]

Schizophrenia

A 2016 systematic review compared the efficacy of valproate as an add-on for people with schizophrenia:[14]

| Summary | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| There is limited evidence that the augmentation of antipsychotics with valproate may be effective for overall response and also for specific symptoms, especially in terms of excitement and aggression. Evidence was entirely based on open randomized controlled trials. Valproate was associated with a number of adverse events among which sedation and dizziness appeared significantly more frequently than in the control groups.[14] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Dopamine dysregulation syndrome

Valproic acid may have efficacy in controlling the symptoms of the dopamine dysregulation syndrome that arise from the treatment of Parkinson's disease with dopamine receptor agonists.[15][16][17]

Migraines

Valproate is also used to prevent migraine headaches. Because this medication can be potentially harmful to the fetus, valproate should be considered for women of childbearing potential only after the risks have been discussed.[18]

Other

The medication has been tested in the treatment of AIDS and cancer, owing to its histone deacetylase-inhibiting effects.[19]

Adverse effects

Most common adverse effects include:[18]

- Nausea (22%)

- Drowsiness (19%)

- Dizziness (12%)

- Vomiting (12%)

- Weakness (10%)

Serious adverse effects include:[18]

- Bleeding

- Low blood platelets

- Encephalopathy

- Suicidal behavior and thoughts

- Low body temperature

Valproic acid has a black box warning for hepatotoxicity, pancreatitis, and fetal abnormalities.[18]

Other possible side effects

There is evidence that valproic acid may cause premature growth plate ossification in children and adolescents, resulting in decreased height.[20][21][22][23] Valproic acid can also cause mydriasis, a dilation of the pupils.[24] There is evidence that shows valproic acid may increase the chance of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) in women with epilepsy or bipolar disorder. Studies have shown this risk of PCOS is higher in women with epilepsy compared to those with bipolar disorder.[25]

Pregnancy

Valproate causes birth defects;[26] exposure during pregnancy is associated with about three times as many major abnormalities as usual, mainly spina bifida with the risks being related to the strength of medication used and use of more than one drug.[27][28] More rarely, with several other defects, possibly including a "valproate syndrome".[29] Characteristics of this valproate syndrome include facial features that tend to evolve with age, including a triangle-shaped forehead, tall forehead with bifrontal narrowing, epicanthic folds, medial deficiency of eyebrows, flat nasal bridge, broad nasal root, anteverted nares, shallow philtrum, long upper lip and thin vermillion borders, thick lower lip and small downturned mouth.[30] While developmental delay is usually associated with altered physical characteristics (dysmorphic features), this is not always the case.[31]

Children of mothers taking valproate during pregnancy are at risk for lower IQs.[32][33][34] Maternal valproate use during pregnancy has been associated with a significantly higher probability of autism in the offspring.[35] A 2005 study found rates of autism among children exposed to sodium valproate before birth in the cohort studied were 8.9%.[36] The normal incidence for autism in the general population is estimated at less than one percent.[37] A 2009 study found that the 3-year-old children of pregnant women taking valproate had an IQ nine points lower than that of a well-matched control group. However, further research in older children and adults is needed.[38][39][40]

Sodium valproate has been associated with the rare condition paroxysmal tonic upgaze of childhood, also known as Ouvrier–Billson syndrome, from childhood or fetal exposure. This condition resolved after discontinuing valproate therapy.[41][42]

Women who intend to become pregnant should switch to a different medication if possible, or decrease their dose of valproate.[43] Women who become pregnant while taking valproate should be warned that it causes birth defects and cognitive impairment in the newborn, especially at high doses (although valproate is sometimes the only drug that can control seizures, and seizures in pregnancy could have even worse consequences.) Studies have shown that taking folic acid can reduce the risk of congenital neural tube defects.[18]

Elderly

Valproate in elderly people with dementia caused increased sleepiness. More people stopped the medication for this reason. Additional side effects of weight loss and decreased food intake was also associated in one half of people who become sleepy.[18]

Contraindications

Contraindications include:[44]

- Pregnancy

- Pre-existing acute or chronic liver dysfunction or family history of severe liver inflammation (hepatitis), particularly medicine related.

- Known hypersensitivity to valproate or any of the ingredients used in the preparation

- Urea cycle disorders

- Hepatic porphyria

- Hepatotoxicity[44]

- Mitochondrial disease[44]

- Pancreatitis[44]

- Porphyria[45]

Interactions

Valproate inhibits CYP2C9, glucuronyl transferase, and epoxide hydrolase and is highly protein bound and hence may interact with drugs that are substrates for any of these enzymes or are highly protein bound themselves.[44] It may also potentiate the CNS depressant effects of alcohol.[44] It should not be given in conjunction with other antiepileptics due to the potential for reduced clearance of other antiepileptics (including carbamazepine, lamotrigine, phenytoin and phenobarbitone) and itself.[44] It may also interact with:[18][44][46]

- Aspirin: may increase valproate concentrations. May also interfere with valproate's metabolism.

- Benzodiazepines: may cause CNS depression and there are possible pharmacokinetic interactions.

- Carbapenem antibiotics: reduces valproate levels, potentially leading to seizures.

- Cimetidine: inhibits valproate's metabolism in the liver, leading to increased valproate concentrations.

- Erythromycin: inhibits valproate's metabolism in the liver, leading to increased valproate concentrations.

- Ethosuximide: may increase ethosuximide concentrations and lead to toxicity.

- Felbamate: may increase plasma concentrations of valproate.

- Mefloquine: may increase valproate metabolism combined with the direct epileptogenic effects of mefloquine.

- Oral contraceptives: may reduce plasma concentrations of valproate.

- Primidone: may accelerate metabolism of valproate, leading to a decline of serum levels and potential breakthrough seizure.

- Rifampin: increases the clearance of valproate, leading to decreased valproate concentrations

- Warfarin: may increase warfarin concentration and prolong bleeding time.

- Zidovudine: may increase zidovudine serum concentration and lead to toxicity.

Overdose and toxicity

| Form | Lower limit | Upper limit | Unit |

| Total (including protein bound) |

50[47] | 125[47] | µg/mL or mg/l |

| 350[48] | 700[48] | μmol/L | |

| Free | 6[47] | 22[47] | µg/mL or mg/l |

| 35[48] | 70[48] | μmol/L |

Excessive amounts of valproic acid can result in sleepiness, tremor, stupor, respiratory depression, coma, metabolic acidosis, and death. In general, serum or plasma valproic acid concentrations are in a range of 20–100 mg/l during controlled therapy, but may reach 150–1500 mg/l following acute poisoning. Monitoring of the serum level is often accomplished using commercial immunoassay techniques, although some laboratories employ gas or liquid chromatography.[49] In contrast to other antiepileptic drugs, at present there is little favorable evidence for salivary therapeutic drug monitoring. Salivary levels of valproic acid correlate poorly with serum levels, partly due to valproate's weak acid property (pKa of 4.9).[50]

In severe intoxication, hemoperfusion or hemofiltration can be an effective means of hastening elimination of the drug from the body.[51][52] Supportive therapy should be given to all patients experiencing an overdose and urine output should be monitored.[18] Supplemental L-carnitine is indicated in patients having an acute overdose[53][54] and also prophylactically[53] in high risk patients. Acetyl-L-carnitine lowers hyperammonemia less markedly[55] than L-carnitine.

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

Although the mechanism of action of valproate is not fully understood,[44] traditionally, its anticonvulsant effect has been attributed to the blockade of voltage-gated sodium channels and increased brain levels of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA).[44] The GABAergic effect is also believed to contribute towards the anti-manic properties of valproate.[44] In animals, sodium valproate raises cerebral and cerebellar levels of the inhibitory synaptic neurotransmitter, GABA, possibly by inhibiting GABA degradative enzymes, such as GABA transaminase, succinate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase and by inhibiting the re-uptake of GABA by neuronal cells.[44]

Prevention of neurotransmitter-induced hyperexcitability of nerve cells, via Kv7.2 channel and AKAP5, may also contribute to its mechanism.[56] Also, it has been shown to protect against a seizure-induced reduction in phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate (PIP3) as a potential therapeutic mechanism.[57]

It also has histone deacetylase-inhibiting effects. The inhibition of histone deacetylase, by promoting more transcriptionally active chromatin structures, likely presents the epigenetic mechanism for regulation of many of the neuroprotective effects attributed to valproic acid. Intermediate molecules mediating these effects include VEGF, BDNF, and GDNF.[58][59]

Endocrine actions

Valproic acid has been found to be an antagonist of the androgen and progesterone receptors, and hence as a nonsteroidal antiandrogen and antiprogestogen, at concentrations much lower than therapeutic serum levels.[60] In addition, the drug has been identified as a potent aromatase inhibitor, and suppresses estrogen concentrations.[61] These actions are likely to be involved in the reproductive endocrine disturbances seen with valproic acid treatment.[60][61]

Valproic acid has been found to directly stimulate androgen biosynthesis in the gonads via inhibition of histone deacetylases and has been associated with hyperandrogenism in women and increased 4-androstenedione levels in men.[62][63] High rates of polycystic ovary syndrome and menstrual disorders have also been observed in women treated with valproic acid.[63]

Chemistry

Valproic acid is a branched short-chain fatty acid and a derivative of valeric acid.[4]

History

Valproic acid was first synthesized in 1882 by Beverly S. Burton as an analogue of valeric acid, found naturally in valerian.[64] Valproic acid is a carboxylic acid, a clear liquid at room temperature. For many decades, its only use was in laboratories as a "metabolically inert" solvent for organic compounds. In 1962, the French researcher Pierre Eymard serendipitously discovered the anticonvulsant properties of valproic acid while using it as a vehicle for a number of other compounds that were being screened for antiseizure activity. He found it prevented pentylenetetrazol-induced convulsions in laboratory rats.[65] It was approved as an antiepileptic drug in 1967 in France and has become the most widely prescribed antiepileptic drug worldwide.[66] Valproic acid has also been used for migraine prophylaxis and bipolar disorder.[67]

Society and culture

Cost

It is available as a generic medication.[2] The wholesale cost in the developing world is between $0.14 and $0.52 USD per day.[8] In the European Union, end-user costs are less than 0.60 EUR for an average daily dose in Germany.[68] In the United States, it costs about $0.90 USD per day.[2]

Approval status

| Indications | FDA-labelled indication?[1] |

TGA-labelled indication?[9] |

MHRA-labelled indication?[69] |

Literature support |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epilepsy | Yes | Yes | Yes | Limited (depends on the seizure type; it can help with certain kinds of seizures: drug-resistant epilepsy, partial and absence seizures, can be used against glioblastoma and other tumors both to improve survival and treat seizures, and against tonic-clonic seizures and status epilepticus).[70][71][72][73] |

| Bipolar mania | Yes | Yes | Yes | Limited.[74] |

| Bipolar depression | No | No | No | Moderate.[75] |

| Bipolar maintenance | No | No | No | Limited.[76] |

| Migraine prophylaxis | Yes | Yes (accepted) | No | Limited. |

| Acute migraine management | No | No | No | Only negative results.[77] |

| Schizophrenia | No | No | No | Weak evidence.[78] |

| Agitation in dementia | No | No | No | Weak and mostly negative evidence.[79] |

| Fragile X syndrome | Yes (orphan) | No | No | Limited.[80] |

| Familial adenomatous polyposis | Yes (orphan) | No | No | Limited. |

| Chronic pain & fibromyalgia | No | No | No | Limited.[81] |

| Alcohol hallucinosis | No | No | No | One randomised double-blind placebo-controlled trial.[82] |

| Intractable hiccups | No | No | No | Limited, five case reports support its efficacy, however.[83] |

| Non-epileptic myoclonus | No | No | No | Limited, three case reports support its efficacy, however.[84] |

| Cluster headaches | No | No | No | Limited, two case reports support its efficacy.[85] |

| West syndrome | No | No | No | A prospective clinical trial supported its efficacy in treating infantile spasms.[86] |

| HIV infection eradication | No | No | No | Double-blind placebo-controlled trials have been negative.[87][88][89] |

| Myelodysplastic syndrome | No | No | No | Several clinical trials have confirmed its efficacy as a monotherapy,[90] as an adjunct to tretinoin[90] and as an adjunct to hydralazine.[91] |

| Acute myeloid leukaemia | No | No | No | Two clinical trials have confirmed its efficacy in this indication as both a monotherapy and as an adjunct to tretinoin.[92][93][94] |

| Cervical cancer | No | No | No | One clinical trial supports its use here.[95] |

| Malignant melanoma | No | No | No | One phase II study has seemed to discount its efficacy.[96] |

| Breast cancer | No | No | No | A phase II study has supported its efficacy.[97] |

| Impulse control disorder | No | No | No | Limited.[98][99] |

Formulations

| |

| |

| Identifiers | |

|---|---|

| |

| CAS Number | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.002.525 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C8H15NaO2 |

| Molar mass | 166.20 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Valproate exists in two main molecular variants: sodium valproate and valproic acid without sodium (often implied by simply valproate). A mixture between these two is termed semisodium valproate. It is unclear whether there is any difference in efficacy between these variants, except from the fact that about 10% more of sodium valproate is needed than valproic acid without sodium to compensate for the sodium itself.[100]

Brand names of valproic acid

Branded products include:

- Absenor (Orion Corporation Finland)

- Convulex (G.L. Pharma GmbH Austria)

- Depakene (Abbott Laboratories in US and Canada)

- Depakine (Sanofi Aventis France)

- Depakine (Sanofi Synthelabo Romania)

- Depalept (Sanofi Aventis Israel)

- Deprakine (Sanofi Aventis Finland)

- Encorate (Sun Pharmaceuticals India)

- Epival (Abbott Laboratories US and Canada)

- Epilim (Sanofi Synthelabo Australia and South Africa)

- Stavzor (Noven Pharmaceuticals Inc.)

- Valcote (Abbott Laboratories Argentina)

- Valpakine (Sanofi Aventis Brazil)

Brand names of sodium valproate

Portugal

- Tablets – Diplexil-R by Bial.

United States

- Intravenous injection – Depacon by Abbott Laboratories.

- Syrup – Depakene by Abbott Laboratories. (Note Depakene capsules are valproic acid).

- Depakote tablets are a mixture of sodium valproate and valproic acid.

- Tablets – Eliaxim by Bial.

Australia

- Epilim Crushable Tablets Sanofi

- Epilim Sugar Free Liquid Sanofi

- Epilim Syrup Sanofi

- Epilim Tablets Sanofi

- Sodium Valproate Sandoz Tablets Sanofi

- Valpro Tablets Alphapharm

- Valproate Winthrop Tablets Sanofi

- Valprease tablets Sigma

New Zealand

- Epilim by Sanofi-Aventis

All the above formulations are Pharmac-subsidised.[101]

UK

- Depakote Tablets (as in USA)

- Tablets – Orlept by Wockhardt and Epilim by Sanofi

- Oral solution – Orlept Sugar Free by Wockhardt and Epilim by Sanofi

- Syrup – Epilim by Sanofi-Aventis

- Intravenous injection – Epilim Intravenous by Sanofi

- Extended release tablets – Epilim Chrono by Sanofi is a combination of sodium valproate and valproic acid in a 2.3:1 ratio.

- Enteric-coated tablets – Epilim EC200 by Sanofi is a 200-mg sodium valproate enteric-coated tablet.

UK only

- Capsules – Episenta prolonged release by Beacon

- Sachets – Episenta prolonged release by Beacon

- Intravenous solution for injection – Episenta solution for injection by Beacon

Germany, Switzerland, Norway, Finland, Sweden

- Tablets – Orfiril by Desitin Pharmaceuticals

- Intravenous injection – Orfiril IV by Desitin Pharmaceuticals

South Africa

- Syrup – Convulex by Byk Madaus

- Tablets – Epilim by Sanofi-synthelabo

Malaysia

- Tablets – Epilim by Sanofi-Aventis

Romania

- Companies are SANOFI-AVENTIS FRANCE, GEROT PHARMAZEUTIKA GMBH and DESITIN ARZNEIMITTEL GMBH

- Types are Syrup, Extended release mini tablets, Gastric resistant coated tablets, Gastric resistant soft capsules, Extended release capsules, Extended release tablets and Extended release coated tablets

Canada

- Intravenous injection – Epival or Epiject by Abbott Laboratories.

- Syrup – Depakene by Abbott Laboratories its generic formulations include Apo-Valproic and ratio-Valproic.

Japan

- Tablets – Depakene by Kyowa Hakko Kirin

- Extended release tablets – Depakene-R by Kyowa Hakko Kogyo and Selenica-R by Kowa

- Syrup – Depakene by Kyowa Hakko Kogyo

Europe

In much of Europe, Dépakine and Depakine Chrono (tablets) are equivalent to Epilim and Epilim Chrono above.

Taiwan

- Tablets (white round tablet) – Depakine (Chinese: 帝拔癲; pinyin: di-ba-dian) by Sanofi Winthrop Industrie (France)

Israel

Depalept and Depalept Chrono (extended release tablets) are equivalent to Epilim and Epilim Chrono above. Manufactured and distributed by Sanofi-Aventis.

India, Russia and CIS countries

- Valprol CR by Intas Pharmaceutical (India)

- Encorate Chrono by Sun Pharmaceutical (India)

- Serven Chrono by Leeven APL Biotech (India)

Brand names of valproate semisodium

- Brazil – Depakote by Abbott Laboratories and Torval CR by Torrent do Brasil

- Canada – Epival by Abbott Laboratories

- Mexico – Epival and Epival ER (extended release) by Abbott Laboratories

- United Kingdom – Depakote (for psychiatric conditions) and Epilim (for epilepsy) by Sanofi-Aventis and generics

- United States – Depakote and Depakote ER (extended release) by Abbott Laboratories and generics

- India – Valance and Valance OD by Abbott Healthcare Pvt Ltd, Divalid ER by Linux laboratories Pvt Ltd, Valex ER by Sigmund Promedica, Dicorate by Sun Pharma

- Germany – Ergenyl Chrono by Sanofi-Aventis and generics

- Chile – Valcote and Valcote ER by Abbott Laboratories

- France and other European countries — Depakote

- Peru – Divalprax by AC Farma Laboratories

- China – Diprate OD

Research

As of 2016 it is also registered for 45 phase II clinical trials (some completed) for various cancers.[102]

References

- 1 2 3 4 "Depakene, Stavzor (valproic acid) dosing, indications, interactions, adverse effects, and more". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Retrieved 13 February 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 "Valproic Acid". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Retrieved Oct 23, 2015.

- ↑ Owens MJ, Nemeroff CB (2003). "Pharmacology of valproate". Psychopharmacol Bull. 37 Suppl 2: 17–24. PMID 14624230.

- 1 2 3 4 Ghodke-Puranik Y, Thorn CF, Lamba JK, Leeder JS, Song W, Birnbaum AK, Altman RB, Klein TE (April 2013). "Valproic acid pathway: pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics". Pharmacogenet. Genomics. 23 (4): 236–241. PMC 3696515

. PMID 23407051. doi:10.1097/FPC.0b013e32835ea0b2.

. PMID 23407051. doi:10.1097/FPC.0b013e32835ea0b2. - ↑ "Valproic acid". DrugBank. University of Alberta. 29 July 2017. Retrieved 30 July 2017.

- ↑ Scott, D.F. (1993). The history of epileptic therapy : an account of how medication was developed (1. publ. ed.). Carnforth u.a.: Parthenon Publ. Group. p. 131. ISBN 9781850703914.

- ↑ "WHO Model List of Essential Medicines (19th List)" (PDF). World Health Organization. April 2015. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- 1 2 "Sodium Valproate". International Drug Price Indicator Guide.

- 1 2 3 Rossi, S, ed. (2013). Australian Medicines Handbook (2013 ed.). Adelaide: The Australian Medicines Handbook Unit Trust. ISBN 978-0-9805790-9-3.

- ↑ Löscher W (2002). "Basic pharmacology of valproate: a review after 35 years of clinical use for the treatment of epilepsy". CNS Drugs. 16 (10): 669–694. PMID 12269861. doi:10.2165/00023210-200216100-00003.

- ↑ Olsen KB, Taubøll E, Gjerstad L (2007). "Valproate is an effective, well-tolerated drug for treatment of status epilepticus/serial attacks in adults". Acta Neurol. Scand. Suppl. 187: 51–4. PMID 17419829. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0404.2007.00847.x.

- ↑ Kwan SY (2010). "The role of intravenous valproate in convulsive status epilepticus in the future" (PDF). Acta Neurol Taiwan. 19 (2): 78–81. PMID 20830628.

- ↑ "Valproate Information". Fda.gov. Retrieved 2015-04-24.

- 1 2 Wang, Y; Xia, J; Helfer, B (2016). "Valproate for schizophrenia". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 11: CD004028.pub4. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004028.pub4.

- ↑ Pirritano D, Plastino M, Bosco D, Gallelli L, Siniscalchi A, De Sarro G (2014). "Gambling disorder during dopamine replacement treatment in Parkinson's disease: a comprehensive review". Biomed Res Int. 2014: 728038. PMC 4119624

. PMID 25114917. doi:10.1155/2014/728038.

. PMID 25114917. doi:10.1155/2014/728038. - ↑ Connolly B, Fox SH (2014). "Treatment of cognitive, psychiatric, and affective disorders associated with Parkinson's disease". Neurotherapeutics. 11 (1): 78–91. PMC 3899484

. PMID 24288035. doi:10.1007/s13311-013-0238-x.

. PMID 24288035. doi:10.1007/s13311-013-0238-x. - ↑ Averbeck BB, O'Sullivan SS, Djamshidian A (2014). "Impulsive and compulsive behaviors in Parkinson's disease". Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 10: 553–80. PMC 4197852

. PMID 24313567. doi:10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032813-153705.

. PMID 24313567. doi:10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032813-153705. - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "DEPAKOTE- divalproex sodium tablet, delayed release". Retrieved 10 November 2015.

- ↑ Činčárová L, Zdráhal Z, Fajkus J (2013). "New perspectives of valproic acid in clinical practice". Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 22 (12): 1535–1547. PMID 24160174. doi:10.1517/13543784.2013.853037.

- ↑ Wu S, Legido A, De Luca F. "Effects of valproic acid on longitudinal bone growth". J Child Neurol. 19: 26–30. PMID 15032379.

- ↑ Robinson PB, Harvey W, Belal MS. "Inhibition of cartilage growth by the anticonvulsant drugs diphenylhydantoin and sodium valproate". Br J Exp Pathol. 69: 17–22. PMC 2013195

. PMID 3126792.

. PMID 3126792. - ↑ Long-Term Valproate and Lamotrigine Treatment May Be a Marker for Reduced Growth and Bone Mass in Children with Epilepsy - Guo - 2002 - Epilepsia - Wiley Online Library

- ↑ Guo CY, Ronen GM, Atkinson SA. "Long-term valproate and lamotrigine treatment may be a marker for reduced growth and bone mass in children with epilepsy". Epilepsia. 42: 1141–7. PMID 11580761. doi:10.1046/j.1528-1157.2001.416800.x.

- ↑ "Could Depakote cause Mydriasis". eHealthMe.com. 2014-11-18. Retrieved 2015-04-24.

- ↑ Bilo, Leonilda; Meo, Roberta (October 2008). "Polycystic ovary syndrome in women using valproate: a review.". Gynecological Endocrinology. 24: 562–70. PMID 19012099. doi:10.1080/09513590802288259.

- ↑ New evidence in France of harm from epilepsy drug valproate BBC, 2017

- ↑ Koch S, Göpfert-Geyer I, Jäger-Roman E, et al. (February 1983). "[Anti-epileptic agents during pregnancy. A prospective study on the course of pregnancy, malformations and child development]". Dtsch. Med. Wochenschr. (in German). 108 (7): 250–7. PMID 6402356. doi:10.1055/s-2008-1069536.

- ↑ Moore SJ, Turnpenny P, Quinn A, et al. (July 2000). "A clinical study of 57 children with fetal anticonvulsant syndromes". J. Med. Genet. 37 (7): 489–97. PMC 1734633

. PMID 10882750. doi:10.1136/jmg.37.7.489.

. PMID 10882750. doi:10.1136/jmg.37.7.489. - ↑ Ornoy A (2009). "Valproic acid in pregnancy: how much are we endangering the embryo and fetus?". Reprod. Toxicol. 28 (1): 1–10. PMID 19490988. doi:10.1016/j.reprotox.2009.02.014.

- ↑ Kulkarni ML, Zaheeruddin M, Shenoy N, Vani HN (2006). "Fetal valproate syndrome". Indian J Pediatr. 73 (10): 937–939. PMID 17090909. doi:10.1007/bf02859291.

- ↑ Adab N, Kini U, Vinten J, et al. (November 2004). "The longer term outcome of children born to mothers with epilepsy". J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatr. 75 (11): 1575–83. PMC 1738809

. PMID 15491979. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2003.029132.

. PMID 15491979. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2003.029132. This argues that the fetal valproate syndrome constitutes a real clinical entity that includes developmental delay and cognitive impairments, but that some children might exhibit some developmental delay without marked dysmorphism.

- ↑ Umur AS, Selcuki M, Bursali A, Umur N, Kara B, Vatansever HS, Duransoy YK (2012). "Simultaneous folate intake may prevent adverse effect of valproic acid on neurulating nervous system". Childs Nerv Syst. 28 (5): 729–737. PMID 22246336. doi:10.1007/s00381-011-1673-9.

- ↑ Cassels, Caroline (December 8, 2006). "NEAD: In Utero Exposure To Valproate Linked to Poor Cognitive Outcomes in Kids". Medscape. Retrieved 2007-05-23.

- ↑ Meador KJ, Baker GA, Finnell RH, Kalayjian LA, Liporace JD, Loring DW, Mawer G, Pennell PB, Smith JC, Wolff MC (2006). "In utero antiepileptic drug exposure: fetal death and malformations". Neurology. 67 (3): 407–412. PMC 1986655

. PMID 16894099. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000227919.81208.b2.

. PMID 16894099. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000227919.81208.b2. - ↑ Christensen J, Grønborg TK, Sørensen MJ, Schendel D, Parner ET, Pedersen LH, Vestergaard M (2013). "Prenatal valproate exposure and risk of autism spectrum disorders and childhood autism". JAMA. 309 (16): 1696–1703. PMC 4511955

. PMID 23613074. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.2270.

. PMID 23613074. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.2270. - ↑ Rasalam AD, Hailey H, Williams JH, et al. (August 2005). "Characteristics of fetal anticonvulsant syndrome associated autistic disorder". Dev Med Child Neurol. 47 (8): 551–5. PMID 16108456. doi:10.1017/S0012162205001076.

- ↑ Autism Society of America: About Autism

- ↑ I.Q. Harmed by Epilepsy Drug in Utero By RONI CARYN RABIN, New York Times, April 15, 2009

- ↑ Meador KJ, Baker GA, Browning N, Clayton-Smith J, Combs-Cantrell DT, Cohen M, Kalayjian LA, Kanner A, Liporace JD, Pennell PB, Privitera M, Loring DW (2009). "Cognitive function at 3 years of age after fetal exposure to antiepileptic drugs". N. Engl. J. Med. 360 (16): 1597–1605. PMC 2737185

. PMID 19369666. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0803531.

. PMID 19369666. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0803531. - ↑ Valproate Products: Drug Safety Communication - Risk of Impaired Cognitive Development in Children Exposed In Utero (During Pregnancy). FDA. June 2011

- ↑ Luat, AF (20 September 2007). "Paroxysmal tonic upgaze of childhood with co-existent absence epilepsy.". Epileptic Disorders. 9: 332–6. PMID 17884759. doi:10.1684/epd.2007.0119.

- ↑ Ouvrier, RA (July 1988). "Benign paroxysmal tonic upgaze of childhood.". Journal of Child Neurology. 3: 177–80. PMID 3209843. doi:10.1177/088307388800300305.

- ↑ Valproate Not To Be Used for Migraine During Pregnancy, FDA Warns

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 "Valpro sodium valproate" (PDF). TGA eBusiness Services. Alphapharm Pty Limited. 16 December 2013. Retrieved 14 February 2014.

- ↑ "Depakote 250mg Tablets - Summary of Product Characteristics". electronic Medicines Compendium. Sanofi. 28 November 2013. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- ↑ Herzog, Andrew; Farina, Erin (June 9, 2005). "Serum Valproate Levels with Oral Contraceptive Use". Epilepsia. 46: 970–971. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1167.2005.00605.x.

- 1 2 3 4 Bentley, Suzanne (Dec 11, 2013). "Valproic Acid Level". Medscape. Retrieved 2015-06-05.

- 1 2 3 4 "Free Valproic Acid Assay (Reference — 2013.03.006) Notice of Assessment" (PDF). Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH) with INESSS’s permission. April 2014. Retrieved 2015-06-05.

- ↑ Sztajnkrycer MD (2002). "Valproic acid toxicity: overview and management". J. Toxicol. Clin. Toxicol. 40 (6): 789–801. PMID 12475192. doi:10.1081/CLT-120014645.

- ↑ Patsalos PN, Berry DJ (2013). "Therapeutic drug monitoring of antiepileptic drugs by use of saliva". Ther Drug Monit. 35 (1): 4–29. PMID 23288091. doi:10.1097/FTD.0b013e31827c11e7.

- ↑ Thanacoody RH (2009). "Extracorporeal elimination in acute valproic acid poisoning". Clin Toxicol (Phila). 47 (7): 609–616. PMID 19656009. doi:10.1080/15563650903167772.

- ↑ R. Baselt, Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man, 8th edition, Biomedical Publications, Foster City, CA, 2008, pp. 1622-1626.

- 1 2 Lheureux PE, Penaloza A, Zahir S, Gris M (2005). "Science review: carnitine in the treatment of valproic acid-induced toxicity - what is the evidence?". Crit Care. 9 (5): 431–440. PMC 1297603

. PMID 16277730. doi:10.1186/cc3742.

. PMID 16277730. doi:10.1186/cc3742. - ↑ Mock CM, Schwetschenau KH (2012). "Levocarnitine for valproic-acid-induced hyperammonemic encephalopathy". Am J Health Syst Pharm. 69 (1): 35–39. PMID 22180549. doi:10.2146/ajhp110049.

- ↑ Matsuoka M, Igisu H (1993). "Comparison of the effects of L-carnitine, D-carnitine and acetyl-L-carnitine on the neurotoxicity of ammonia". Biochem. Pharmacol. 46 (1): 159–164. PMID 8347126. doi:10.1016/0006-2952(93)90360-9.

- ↑ Kay, Hee Yeon; Greene, Derek L.; Kang, Seungwoo; Kosenko, Anastasia; Hoshi, Naoto (2015-10-01). "M-current preservation contributes to anticonvulsant effects of valproic acid". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 125 (10): 3904–3914. ISSN 0021-9738. PMC 4607138

. PMID 26348896. doi:10.1172/JCI79727.

. PMID 26348896. doi:10.1172/JCI79727. - ↑ Chang P, Walker MC, Williams RS (2014). "Seizure-induced reduction in PIP3 levels contributes to seizure-activity and is rescued by valproic acid". Neurobiol. Dis. 62: 296–306. PMC 3898270

. PMID 24148856. doi:10.1016/j.nbd.2013.10.017.

. PMID 24148856. doi:10.1016/j.nbd.2013.10.017. - ↑ Kostrouchová M, Kostrouch Z, Kostrouchová M (2007). "Valproic acid, a molecular lead to multiple regulatory pathways" (PDF). Folia Biol. (Praha). 53 (2): 37–49. PMID 17448293.

- ↑ Chiu CT, Wang Z, Hunsberger JG, Chuang DM (2013). "Therapeutic potential of mood stabilizers lithium and valproic acid: beyond bipolar disorder". Pharmacol. Rev. 65 (1): 105–142. PMC 3565922

. PMID 23300133. doi:10.1124/pr.111.005512.

. PMID 23300133. doi:10.1124/pr.111.005512. - 1 2 Death AK, McGrath KC, Handelsman DJ (2005). "Valproate is an anti-androgen and anti-progestin". Steroids. 70 (14): 946–53. PMID 16165177. doi:10.1016/j.steroids.2005.07.003.

- 1 2 Wyllie E, Cascino GD, Gidal BE, Goodkin HP (17 February 2012). Wyllie's Treatment of Epilepsy: Principles and Practice. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 288–. ISBN 978-1-4511-5348-4.

- ↑ Uchida, Hiroshi; Maruyama, Tetsuo; Arase, Toru; Ono, Masanori; Nagashima, Takashi; Masuda, Hirotaka; Asada, Hironori; Yoshimura, Yasunori (2005). "Histone acetylation in reproductive organs: Significance of histone deacetylase inhibitors in gene transcription". Reproductive Medicine and Biology. 4 (2): 115–122. ISSN 1445-5781. doi:10.1111/j.1447-0578.2005.00101.x.

- 1 2 Isojärvi, Jouko I T; Taubøll, Erik; Herzog, Andrew G (2005). "Effect of Antiepileptic Drugs on Reproductive Endocrine Function in Individuals with Epilepsy". CNS Drugs. 19 (3): 207–223. ISSN 1172-7047. doi:10.2165/00023210-200519030-00003.

- ↑ Burton BS (1882). "On the propyl derivatives and decomposition products of ethylacetoacetate". Am Chem J. 3: 385–395.

- ↑ Meunier H, Carraz G, Neunier Y, Eymard P, Aimard M (1963). "[Pharmacodynamic properties of N-dipropylacetic acid]" [Pharmacodynamic properties of N-dipropylacetic acid]. Therapie (in French). 18: 435–438. PMID 13935231.

- ↑ Perucca E (2002). "Pharmacological and therapeutic properties of valproate: a summary after 35 years of clinical experience". CNS Drugs. 16 (10): 695–714. PMID 12269862. doi:10.2165/00023210-200216100-00004.

- ↑ Henry TR (2003). "The history of valproate in clinical neuroscience". Psychopharmacol Bull. 37 Suppl 2: 5–16. PMID 14624229.

- ↑ Regular pharmacy price, including all taxes, et cetera: less than 34,43 EUR for 200 controlled release pills with 500mg each; date: 2016-11-30

- ↑ Joint Formulary Committee. British National Formulary (BNF) (65 ed.). London, UK: Pharmaceutical Press. ISBN 978-0-85711-084-8.

- ↑ Rimmer EM, Richens A (May–June 1985). "An update on sodium valproate". Pharmacotherapy. 5 (3): 171–84. PMID 3927267. doi:10.1002/j.1875-9114.1985.tb03413.x.

- ↑ http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa0902014

- ↑ http://www.neurology.org/content/84/14_Supplement/P1.238.short

- ↑ http://neuro-oncology.oxfordjournals.org/content/16/suppl_2/ii21.3.short

- ↑ Vasudev K, Mead A, Macritchie K, Young AH (2012). "Valproate in acute mania: is our practice evidence based?". Int J Health Care Qual Assur. 25 (1): 41–52. PMID 22455007. doi:10.1108/09526861211192395.

- ↑ Bond DJ, Lam RW, Yatham LN (2010). "Divalproex sodium versus placebo in the treatment of acute bipolar depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis". J Affect Disord. 124 (3): 228–334. PMID 20044142. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2009.11.008.

- ↑ Haddad PM, Das A, Ashfaq M, Wieck A (2009). "A review of valproate in psychiatric practice". Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 5 (5): 539–51. PMID 19409030. doi:10.1517/17425250902911455.

- ↑ Frazee LA, Foraker KC (2008). "Use of intravenous valproic acid for acute migraine". Ann Pharmacother. 42 (3): 403–7. PMID 18303140. doi:10.1345/aph.1K531.

- ↑ Wang, Yijun; Xia, Jun; Helfer, Bartosz; Li, Chunbo; Leucht, Stefan (2016). "Valproate for schizophrenia". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 11: CD004028. ISSN 1469-493X. PMID 27884042. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004028.pub4.

- ↑ Lonergan E, Luxenberg J (2009). "Valproate preparations for agitation in dementia" (PDF). Cochrane Database Syst Rev (3): CD003945. PMID 19588348. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003945.pub3.

- ↑ Chiu CT, Wang Z, Hunsberger JG, Chuang DM (2013). "Therapeutic potential of mood stabilizers lithium and valproic acid: beyond bipolar disorder" (PDF). Pharmacol. Rev. 65 (1): 105–142. PMC 3565922

. PMID 23300133. doi:10.1124/pr.111.005512.

. PMID 23300133. doi:10.1124/pr.111.005512. - ↑ Gill D, Derry S, Wiffen PJ, Moore RA (2011). "Valproic acid and sodium valproate for neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia in adults" (PDF). Cochrane Database Syst Rev (10): CD009183. PMID 21975791. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009183.pub2.

- ↑ Aliyev ZN, Aliyev NA (July–August 2008). "Valproate treatment of acute alcohol hallucinosis: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study" (PDF). Alcohol Alcohol. 43 (4): 456–459. PMID 18495806. doi:10.1093/alcalc/agn043.

- ↑ Jacobson PL, Messenheimer JA, Farmer TW (1981). "Treatment of intractable hiccups with valproic acid". Neurology. 31 (11): 1458–1458. PMID 6796902. doi:10.1212/WNL.31.11.1458.

- ↑ Sotaniemi K (1982). "Valproic acid in the treatment of nonepileptic myoclonus". Arch. Neurol. 39 (7): 448–9. PMID 6808975. doi:10.1001/archneur.1982.00510190066025.

- ↑ Wheeler SD (July–August 1998). "Significance of migrainous features in cluster headache: divalproex responsiveness". Headache. 38 (7): 547–51. PMID 15613172. doi:10.1046/j.1526-4610.1998.3807547.x.

- ↑ Siemes H, Spohr HL, Michael T, Nau H (September–October 1988). "Therapy of infantile spasms with valproate: results of a prospective study". Epilepsia. 29 (5): 553–60. PMID 2842127. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1157.1988.tb03760.x.

- ↑ Smith SM (2005). "Valproic acid and HIV-1 latency: beyond the sound bite" (PDF). Retrovirology. 2 (1): 56. PMC 1242254

. PMID 16168066. doi:10.1186/1742-4690-2-56.

. PMID 16168066. doi:10.1186/1742-4690-2-56. - ↑ Routy JP, Tremblay CL, Angel JB, Trottier B, Rouleau D, Baril JG, Harris M, Trottier S, Singer J, Chomont N, Sékaly RP, Boulassel MR (2012). "Valproic acid in association with highly active antiretroviral therapy for reducing systemic HIV-1 reservoirs: results from a multicentre randomized clinical study". HIV Med. 13 (5): 291–6. PMID 22276680. doi:10.1111/j.1468-1293.2011.00975.x.

- ↑ Archin NM, Cheema M, Parker D, Wiegand A, Bosch RJ, Coffin JM, Eron J, Cohen M, Margolis DM (2010). "Antiretroviral intensification and valproic acid lack sustained effect on residual HIV-1 viremia or resting CD4+ cell infection" (PDF). PLoS ONE. 5 (2): e9390. PMC 2826423

. PMID 20186346. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0009390.

. PMID 20186346. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0009390. - 1 2 Hardy JR, Rees EA, Gwilliam B, Ling J, Broadley K, A'Hern R (2001). "A phase II study to establish the efficacy and toxicity of sodium valproate in patients with cancer-related neuropathic pain" (PDF). J Pain Symptom Manage. 21 (3): 204–9. PMID 11239739. doi:10.1016/S0885-3924(00)00266-9.

- ↑ Candelaria M, Herrera A, Labardini J, González-Fierro A, Trejo-Becerril C, Taja-Chayeb L, Pérez-Cárdenas E, de la Cruz-Hernández E, Arias-Bofill D, Vidal S, Cervera E, Dueñas-Gonzalez A (2011). "Hydralazine and magnesium valproate as epigenetic treatment for myelodysplastic syndrome. Preliminary results of a phase-II trial". Ann. Hematol. 90 (4): 379–387. PMID 20922525. doi:10.1007/s00277-010-1090-2.

- ↑ Bug G, Ritter M, Wassmann B, Schoch C, Heinzel T, Schwarz K, Romanski A, Kramer OH, Kampfmann M, Hoelzer D, Neubauer A, Ruthardt M, Ottmann OG (2005). "Clinical trial of valproic acid and all-trans retinoic acid in patients with poor-risk acute myeloid leukemia" (PDF). Cancer. 104 (12): 2717–2725. PMID 16294345. doi:10.1002/cncr.21589.

- ↑ Kuendgen A, Schmid M, Schlenk R, Knipp S, Hildebrandt B, Steidl C, Germing U, Haas R, Dohner H, Gattermann N (2006). "The histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor valproic acid as monotherapy or in combination with all-trans retinoic acid in patients with acute myeloid leukemia" (PDF). Cancer. 106 (1): 112–119. PMID 16323176. doi:10.1002/cncr.21552.

- ↑ Fredly H, Gjertsen BT, Bruserud O (2013). "Histone deacetylase inhibition in the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia: the effects of valproic acid on leukemic cells, and the clinical and experimental evidence for combining valproic acid with other antileukemic agents" (PDF). Clin Epigenetics. 5 (1): 12. PMC 3733883

. PMID 23898968. doi:10.1186/1868-7083-5-12.

. PMID 23898968. doi:10.1186/1868-7083-5-12. - ↑ Coronel J, Cetina L, Pacheco I, Trejo-Becerril C, González-Fierro A, de la Cruz-Hernandez E, Perez-Cardenas E, Taja-Chayeb L, Arias-Bofill D, Candelaria M, Vidal S, Dueñas-González A (2011). "A double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized phase III trial of chemotherapy plus epigenetic therapy with hydralazine valproate for advanced cervical cancer. Preliminary results". Med. Oncol. 28 Suppl 1: S540–6. PMID 20931299. doi:10.1007/s12032-010-9700-3.

- ↑ Rocca A, Minucci S, Tosti G, Croci D, Contegno F, Ballarini M, Nolè F, Munzone E, Salmaggi A, Goldhirsch A, Pelicci PG, Testori A (2009). "A phase I-II study of the histone deacetylase inhibitor valproic acid plus chemoimmunotherapy in patients with advanced melanoma" (PDF). Br. J. Cancer. 100 (1): 28–36. PMC 2634690

. PMID 19127265. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6604817.

. PMID 19127265. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6604817. - ↑ Munster P, Marchion D, Bicaku E, Lacevic M, Kim J, Centeno B, Daud A, Neuger A, Minton S, Sullivan D (2009). "Clinical and biological effects of valproic acid as a histone deacetylase inhibitor on tumor and surrogate tissues: phase I/II trial of valproic acid and epirubicin/FEC" (PDF). Clin. Cancer Res. 15 (7): 2488–96. PMID 19318486. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1930.

- ↑ Hicks CW, Pandya MM, Itin I, Fernandez HH (2011). "Valproate for the treatment of medication-induced impulse-control disorders in three patients with Parkinson's disease". Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 17 (5): 379–81. PMID 21459656. doi:10.1016/j.parkreldis.2011.03.003.

- ↑ Sriram A, Ward HE, Hassan A, Iyer S, Foote KD, Rodriguez RL, McFarland NR, Okun MS (2013). "Valproate as a treatment for dopamine dysregulation syndrome (DDS) in Parkinson's disease". J. Neurol. 260 (2): 521–7. PMID 23007193. doi:10.1007/s00415-012-6669-1.

- ↑ David Taylor; Carol Paton; Shitij Kapur (2009). The Maudsley Prescribing Guidelines, Tenth Edition (10, revised ed.). CRC Press. p. 124. ISBN 9780203092835.

- ↑ "Sodium valproate -- Pharmaceutical Schedule". Pharmaceutical Management Agency. Retrieved 22 June 2014.

- ↑ Phase II cancer trials of valproic acid

Further reading

- Chateauvieux S, Morceau F, Dicato M, Diederich M (2010). "Molecular and therapeutic potential and toxicity of valproic acid" (PDF). J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2010: 1–18. PMC 2926634

. PMID 20798865. doi:10.1155/2010/479364.

. PMID 20798865. doi:10.1155/2010/479364. - Monti B, Polazzi E, Contestabile A (2009). "Biochemical, molecular and epigenetic mechanisms of valproic acid neuroprotection" (PDF). Curr Mol Pharmacol. 2 (1): 95–109. PMID 20021450. doi:10.2174/1874467210902010095.

External links

- PsychEducation: Valproate/divalproex (divalproex)

- The Comparative Toxicogenomics Database:Valproic Acid

- Chemical Land21: Valproic Acid

- RXList.com: Depakene (Valproic Acid) (U.S.)

- South African Electronic Package Inserts: Convulex

- Med Broadcast.com: Valproic Acid (Canadian)