Andorra

| Principality of Andorra | |

|---|---|

|

Motto: Virtus Unita Fortior "United virtue is stronger" | |

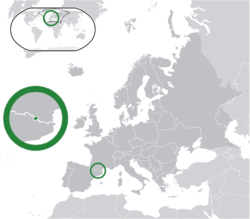

Location of Andorra (center of green circle) in Europe (dark grey) – [Legend] | |

| Capital and largest city |

Andorra la Vella 42°30′N 1°31′E / 42.500°N 1.517°ECoordinates: 42°30′N 1°31′E / 42.500°N 1.517°E |

| Official languages | Catalan |

| Recognised languages | |

| Ethnic groups (2012[1]) |

49% Andorran 24.6% Spanish 14.3% Portuguese 3.9% French 8.2% others |

| Demonym | Andorran |

| Government | Unitary parliamentary semi-elective diarchy |

|

Joan Enric Vives Sicília Emmanuel Macron | |

|

Josep Maria Mauri Patrick Strzoda | |

| Antoni Martí | |

| Legislature | General Council |

| Independence | |

• from Aragon | 1278 |

• from the French Empire | 1814 |

| 1993 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 467.63 km2 (180.55 sq mi) (179th) |

• Water (%) | 0.26 (121.4 ha)b |

| Population | |

• 2014 estimate | 85,470 |

• Density | 179.8/km2 (465.7/sq mi) (71st) |

| GDP (nominal) | 2014 estimate |

• Total | $3.3 billion[2] (155th) |

• Per capita | $45,000[3] (9th) |

| Gini (2003) |

27.21c low |

| HDI (2015) |

very high · 32nd |

| Currency | Eurod (EUR) |

| Time zone | CET (UTC+1) |

| CEST (UTC+2) | |

| Drives on the | right |

| Calling code | +376 |

| ISO 3166 code | AD |

| Internet TLD | .ade |

| |

Andorra (/ænˈdɔːrə/; Catalan: [ənˈdorə], locally [anˈdɔra]), officially the Principality of Andorra (Catalan: Principat d'Andorra), also called the Principality of the Valleys of Andorra[5] (Catalan: Principat de les Valls d'Andorra), is a sovereign landlocked microstate in Southwestern Europe, located in the eastern Pyrenees mountains and bordered by Spain and France. Created under a charter in 988, the present principality was formed in 1278. It is known as a principality as it is a diarchy headed by two Co-Princes – the Catholic Bishop of Urgell in Spain, and the President of France.

Andorra is the sixth-smallest nation in Europe, having an area of 468 km2 (181 sq mi) and a population of approximately 85,000.[1] Andorra is the 16th-smallest country in the world by land and 11th-smallest country by population.[6] Its capital Andorra la Vella is the highest capital city in Europe, at an elevation of 1,023 metres (3,356 feet) above sea level.[7] The official language is Catalan, although Spanish, Portuguese, and French are also commonly spoken.[1][8]

Andorra's tourism services an estimated 10.2 million visitors annually.[9] It is not a member of the European Union, but the euro is the official currency. It has been a member of the United Nations since 1993.[10] In 2013, the people of Andorra had the highest life expectancy in the world at 81 years, according to The Lancet.[11]

Etymology

The origin of the word Andorra is unknown, although several hypotheses have been formulated. The oldest derivation of the word Andorra is from the Greek historian Polybius (The Histories III, 35, 1) who describes the Andosins, an Iberian Pre-Roman tribe, as historically located in the valleys of Andorra and facing the Carthaginian army in its passage through the Pyrenees during the Punic Wars. The word Andosini or Andosins (Ἀνδοσίνους) may derive from the Basque handia whose meaning is "big" or "giant".[12] The Andorran toponymy shows evidence of Basque language in the area. Another theory suggests that the word Andorra may derive from the old word Anorra that contains the Basque word ur (water).[13]

Another theory suggests that Andorra may derive from Arabic al-durra, meaning "The forest" (الدرة). When the Moors colonized the Iberian Peninsula, the valleys of the Pyrenees were covered by large tracts of forest, and other regions and towns, also administered by Muslims, received this designation.[14]

Other theories suggest that the term derives from the Navarro-Aragonese andurrial, which means "land covered with bushes" or "scrubland".[15]

The folk etymology holds that Charlemagne had named the region as a reference to the Biblical Canaanite valley of Endor or Andor (where the Midianites had been defeated), a name also bestowed by his heir and son Louis le Debonnaire after defeating the Moors in the "wild valleys of Hell".[16]

History

Prehistory

La Balma de la Margineda found by archaeologists at Sant Julia de Loria were the first temporal settled in 10,000 BC as a passing place between the two sides of the Pyrenees. The seasonal camp was perfectly located for hunting and fishing by the groups of hunter-gatherers from Ariege and Segre.[17]

During the Neolithic Age the group of humans moved to the Valley of Madriu (nowaday Natural Parc located in Escaldes-Engordany declared UNESCO World Heritage Site) as a permanent camp in 6640 BC. The population of the valley grew cereals, raised domestic livestock and developed a commercial trade with people from the Segre and Occitania.[18][19]

Other archaeological deposits include the Tombs of Segudet (Ordino) and Feixa del Moro (Sant Julia de Loria) both dated in 4900–4300 BC as an example of the Urn culture in Andorra.[18][19] The model of small settlements begin to evolved as a complex urbanism during the Bronze Age. Metallurgical items of iron, ancient coins and relicaries can be found in the ancient sanctuaries scattered around the country.

The sanctuary of Roc de les Bruixes (Stone of the Witches) is maybe the most important archeological complex of this Age in Andorra, located in the parish of Canillo, about the rituals of funerals, ancient scripture and engraved stone murals.[20][19]

The Iberian and Roman Andorra

The inhabitants of the valleys were traditionally associated with the Iberians and historically located in Andorra as the Iberian tribe Andosins or Andosini (Ἀνδοσίνους) during the VII and II centuries BC. Influenced by Aquitanias, Basque and Iberian languages the locals developed some current toponyms. Early writings and documents relating this group of people goes back to the second century BC by the Greek writer Polybius in his Histories during the Punic Wars.[21][22][19][23]

Some of the most significant remains of this era are the Castle of the Roc d'Enclar (part of the early Marca Hispanica),[24] l'Anxiu in Les Escaldes and Roc de L'Oral in Encamp.[19][23] It is known the presence of Roman influence from the II century BC to the V century AD. The places found with more Roman presence are in Camp Vermell (Red Field) in Sant Julia de Loria and in some places in Encamp as well as in the Roc d'Enclar. People continued trading, mainly with wine and cereals, with the Roman cities of Urgellet (nowaday La Seu d'Urgell) and all across Segre through the Via Romana Strata Ceretana (also known as Strata Confluetana).[25][19] [24][19]

The Visigoths and Carolingians: the legend of Charlemagne

After the fall of the Roman Empire Andorra was under the influence of the Visigoths, not directly from the Kingdom of Toledo by distance, but more particular from the Diocese of Urgell. The Visigoths remained during 200 years in the valleys, a period in which Christianization takes place within the country. The fall of the Visigoths came from the Muslim Empire and its conquest of the Iberian Peninsula. Andorra remained away from these invasions by the Franks.[26]

Tradition holds that Charles the Great (Charlemagne) granted a charter to the Andorran people, under the command of Marc Almugaver and an army of five thousand soldiers, in return for fighting against the Moors near Porté-Puymorens (Cerdanya).[27]

Andorra remained part of the Marca Hispanica of the Frankish Empire being overlordship of the territory the Count of Urgell and eventually by the bishop of the Diocese of Urgell. Also tradition holds that it was guaranteed by the son of Charlemagne, Louis the Pious, writing the Carta de Poblament or a local municipal charter circa 805.[28]

In 988, Borrell II, Count of Urgell, gave the Andorran valleys to the Diocese of Urgell in exchange for land in Cerdanya.[29] Since then the Bishop of Urgell, based in Seu d'Urgell, has been Co-prince of Andorra.[30]

The first document that mentions Andorra as a territory is the Acta de Consagració i Dotació de la Catedral de la Seu d'Urgell (Deed of Consecration and Endowment of the Cathedral of La Seu d'Urgell). The old document dated from 839 depicts the six old parishes of the Andorran valleys and therefore the administrative division of the country.[31]

Medieval Age: The Paréages and the founding of the Co-Principality

Before 1095, Andorra did not have any type of military protection and the Bishop of Urgell, who knew that the Count of Urgell wanted to reclaim the Andorran valleys,[30] asked the Lord of Caboet for help and protection. In 1095 the Lord of Caboet and the Bishop of Urgell signed under oath a declaration of their co-sovereignty over Andorra. Arnalda, daughter of Arnau of Caboet, married the Viscount of Castellbò and both became Viscounts of Castellbò and Cerdanya. Years later their daughter, Ermessenda,[32] married Roger Bernat II, the French Count of Foix. They became Roger Bernat II and Ermessenda I, Counts of Foix, Viscounts of Castellbò and Cerdanya, and co-sovereigns of Andorra (shared with the Bishop of Urgell).

In the 13th century, a military dispute arose between the Bishop of Urgell and the Count of Foix as aftermath of the Cathar Crusade. The conflict was resolved in 1278 with the mediation of the king of Aragon, Pere II between the Bishop and the Count, by the signing of the first paréage which provided that Andorra's sovereignty be shared between the count of Foix[30] (whose title would ultimately transfer to the French head of state) and the Bishop of Urgell, in Catalonia. This gave the principality its territory and political form.[31][33][34]

A second paréage was signed in 1288 after a dispute when the Count of Foix ordered the construction of a castle in Roc d'Enclar.[31][33][34] The document was ratified by the noble notary Jaume Orig of Puigcerdà and the construction of military structures in the country was prohibited.[36][31]

In 1364 the political organization of the country named the figure of the syndic (now spokesman and president of the parliament) as representative of the Andorrans to their co-princes making possible the creation of local departments (comuns, quarts and veïnats). After being ratified by the Bishop Francesc Tovia and the Count Jean I, the Consell de la Terra or Consell General de les Valls (General Council of the Valleys) was founded in 1419, the second oldest parliament in Europe. The syndic Andreu d'Alàs and the General Council organized the creation of the Justice Courts (La Cort de Justicia) in 1433 with the Co-Princes and the collection of taxes like foc i lloc (literally fire and site, a national tax active since then).[37][26]

Although we can find remains of ecclesiastical works dating before the 9th century (Sant Vicenç d'Enclar or Església de Santa Coloma), Andorra developed an exquisite Romanesque Art during the 9th and 14th centuries, as much in the construction of churches, bridges, religious murals and statues of the Virgin and Child (being the most important the Our Lady of Meritxell).[26] Nowadays, the Romanesque buildings that form part of Andorra's cultural heritage stand out in a remarkable way, with an emphasis on Església de Sant Esteve, Sant Joan de Caselles, Església de Sant Miquel d'Engolasters, Sant Martí de la Cortinada and the medieval bridges of Margineda and Escalls among many others.[38][39][40]

While the Catalan Pyrenees were embryonic of the Catalan language at the end of the 11th century Andorra was influenced by the appearance of that language where it was adopted by proximity and influence even decades before it was expanded by the rest of the Kingdom of Aragon.[41]

The local population based its economy during the Middle Ages in the livestock and agriculture, as well as in furs and weavers. Later, at the end of the 11th century, the first foundries of iron began to appear in Northern Parishes like Ordino, much appreciated by the master artisans who developed the art of the forges, an important economic activity in the country from the 15th century.[26][42]

16th to 18th centuries

In 1601 the Tribunal de Corts (High Court of Justice) was created as a result of Huguenot rebellions from France, Inquisition courts coming from Spain and indigenous witchcraft experienced in the country due to the Reformation and Counter-Reformation.[43][44][45][45] With the passage of time, the co-title to Andorra passed to the kings of Navarre. After Henry of Navarre became King Henry IV of France, he issued an edict in 1607, that established the head of the French state and the Bishop of Urgell as Co-Princes of Andorra. During 1617 communal councils form the sometent (popular militia or army) to deal with the rise of bandolerisme (brigandage) and the Consell de la Terra was defined and structured in terms of its composition, organization and competences current today .[43][46][47]

Andorra continues with the same economic system that it had during the 12th-14th centuries with a large production of metallurgy (fargues, a system similar to Farga catalana) and with the introduction of tobacco circa 1692 and import trade. The fair of Andorra la Vella was ratified by the co-princes in 1371 and 1448 being the most important annual national festival commercially ever since.[48][49][50]

The country had a unique and experienced guild of weavers, Confraria de Paraires i Teixidors, located in Escaldes-Engordany founded in 1604 taking advantage of the thermal waters of the area. By the time the country constitutes the social system of prohoms (wealthy society) and casalers (rest of the population with smaller economic acquisition), deriving to the tradition of pubilla and hereu.[52][53][54][55]

Three centuries after its foundation the Consell de la Terra locates its headquarters and the Tribunal de Corts in Casa de la Vall in 1702. The manor house built in 1580 served as a noble fortress of the Busquets family. Inside the parliament was placed the Closet of the six keys (Armari de les sis claus) representative of each Andorran parish and where the Andorran constitution and other documents and laws were kept later on.[56][57]

In both Guerra dels Segadors and Guerra de Sucesión Española conflicts, the Andorran people (although with the statement neutral country) supported the Catalans who saw their rights reduced in 1716. The reaction was the promotion of Catalan writings in Andorra, with cultural works such as the Book of Privileges (Llibre de Privilegis de 1674), Manual Digest (1748) by Antoni Fiter i Rossell or the Polità andorrà (1763) by Antoni Puig.[58][58][58][59]

19th century: the New Reform and the Andorran Question

After the French Revolution Napoleon I reestablished in 1809 the Co-Principate and deleted the French medieval tithe. Although in 1812–13, the First French Empire annexed Catalonia during the Peninsular War (Guerra del francés) and divided it in four départements, with Andorra being made part of the district of Puigcerdà (département of Sègre). In 1814 a royal decree reestablished the independence and economy of Andorra.[60][61][62]

Andorra retained its late medieval institutions and rural culture largely unchanged during this period. In 1866 the syndic Guillem d'Areny-Plandolit lead the reformist group in a Council General of 24 members, elected by suffrage limited to heads of families, replaced the aristocratic oligarchy that previously ruled the state.[63] The New Reform (Nova Reforma or Pla de Reforma) began after being ratified by both Co-Princes and established the basis of the constitution and symbols (such as the tricolor flag) of Andorra. A new service economy arise as a demand of the inhabitants of the valleys and began to build infrastructures such as hotels, spa resorts, roads and telegraph lines.[64][65][66][67]

The authorities of the Co-Princes (veguer) banned casinos and betting houses throughout the country by establishing an economic conflict with the demand of the Andorran people. The conflict led to the so-called Revolution of 1881 or Troubles of Andorra, when revolutionaries assaulted the house of the syndic during 8 December 1880 and established the Provisional Revolutionary Council led by Joan Pla i Calvo and Pere Baró i Mas, who granted the construction of casinos and spas to foreign companies.[69] During 7 and 9 June 1881, the loyalists of Canillo and Encamp reconquered the parishes of Ordino and Massana by establishing contact with the revolutionary forces in Escaldes-Engordany.[70] After a day of combat finally the Treaty of the Bridge of Escalls was signed the 10 of June.[71][72][73][74][75] The Council was replaced and new elections were made but the economic situation worsened with a divided society: the Qüestió d'Andorra (the Andorran Question in relation to the Eastern Question).[76] The struggles continued between pro-bishops, pro-French and nationalists who derived the troubles of Canillo in 1882 and 1885.[77][78][79]

Andorra participated in the cultural movement of the Catalan Renaixença. Between 1882 and 1887 the first academic schools were formed where trilingualism coexists with the knowledge of the official language, Catalan. Some romantic authors from both France and Spain reported the awakening of the national consciousness of the country. Jacint Verdaguer lived in Ordino during the 1880s where he wrote and share works related to the Renaixença with Joaquim de Riba, writer and photographer. Fromental Halévy, for his part, had already premiered in 1848 the opera Le Val d'Andorre of great success in Europe, where the national consciousness of the valleys during the Peninsular War was exposed in the romantic work.[80][81][82][83][84]

20th century

Andorra declared war on Imperial Germany during World War I, but did not actually take part in the fighting. It remained in an official state of belligerency until 1958 as it was not included in the Treaty of Versailles.[85]

In 1933, France occupied Andorra following social unrest which occurred before elections. On 12 July 1934, adventurer Boris Skossyreff issued a proclamation in Urgell, declaring himself "Boris I, King of Andorra", simultaneously declaring war on the Bishop of Urgell. He was arrested by the Spanish authorities on 20 July and ultimately expelled from Spain. From 1936 until 1940, a French military detachment was garrisoned in Andorra to secure the principality against disruption from the Spanish Civil War and Francoist Spain. Francoist troops reached the Andorran border in the later stages of the war. During World War II, Andorra remained neutral and was an important smuggling route between Vichy France and Spain.

Given its relative isolation, Andorra has existed outside the mainstream of European history, with few ties to countries other than France, Spain and Portugal. In recent times, however, its thriving tourist industry along with developments in transport and communications have removed the country from its isolation. Its political system was modernised in 1993, when it became a member of the United Nations and the Council of Europe.

Politics

.jpg)

.jpg)

Andorra is a parliamentary co-principality with the President of France and the Catholic Bishop of Urgell (Catalonia, Spain) as Co-Princes. This peculiarity makes the President of France, in his capacity as Prince of Andorra, an elected reigning monarch, although he is not elected by a popular vote of the Andorran people. The politics of Andorra take place in a framework of a parliamentary representative democracy, whereby the Head of Government is the chief executive, and of a pluriform multi-party system.

The current Head of Government is Antoni Martí of the Democrats for Andorra (DA). Executive power is exercised by the government. Legislative power is vested in both government and parliament.

The Parliament of Andorra is known as the General Council. The General Council consists of between 28 and 42 Councillors. The Councillors serve for four-year terms, and elections are held between the 30th and 40th days following the dissolution of the previous Council.

Half are elected in equal numbers by each of the seven administrative parishes, and the other half of the Councillors are elected in a single national constituency. Fifteen days after the election, the Councillors hold their inauguration. During this session, the Syndic General, who is the head of the General Council, and the Subsyndic General, his assistant, are elected. Eight days later, the Council convenes once more. During this session the Head of Government is chosen from among the Councillors.

Candidates can be proposed by a minimum of one-fifth of the Councillors. The Council then elects the candidate with the absolute majority of votes to be Head of Government. The Syndic General then notifies the Co-Princes, who in turn appoint the elected candidate as the Head of Government of Andorra. The General Council is also responsible for proposing and passing laws. Bills may be presented to the Council as Private Members' Bills by three of the local Parish Councils jointly or by at least one tenth of the citizens of Andorra.

The Council also approves the annual budget of the principality. The government must submit the proposed budget for parliamentary approval at least two months before the previous budget expires. If the budget is not approved by the first day of the next year, the previous budget is extended until a new one is approved. Once any bill is approved, the Syndic General is responsible for presenting it to the Co-Princes so that they may sign and enact it.

If the Head of Government is not satisfied with the Council, he may request that the Co-Princes dissolve the Council and order new elections. In turn, the Councillors have the power to remove the Head of Government from office. After a motion of censure is approved by at least one-fifth of the Councillors, the Council will vote and if it receives the absolute majority of votes, the Head of Government is removed.

Law and criminal justice

The judiciary is composed of the Magistrates Court, the Criminal Law Court, the High Court of Andorra, and the Constitutional Court. The High Court of Justice is composed of five judges: one appointed by the Head of Government, one each by the Co-Princes, one by the Syndic General, and one by the Judges and Magistrates. It is presided over by the member appointed by the Syndic General and the judges hold office for six-year terms.

The Magistrates and Judges are appointed by the High Court, as is the President of the Criminal Law Court. The High Court also appoints members of the Office of the Attorney General. The Constitutional Court is responsible for interpreting the Constitution and reviewing all appeals of unconstitutionality against laws and treaties. It is composed of four judges, one appointed by each of the Co-Princes and two by the General Council. They serve eight-year terms. The Court is presided over by one of the Judges on a two-year rotation so that each judge at one point will preside over the Court.

Foreign relations, defence, and security

Andorra does not have its own armed forces,[1] although there is a small ceremonial army. Responsibility for defending the nation rests primarily with France and Spain.[86] However, in case of emergencies or natural disasters, the Sometent (an alarm) is called and all able-bodied men between 21 and 60 of Andorran nationality must serve.[87][88] This is why all Andorrans, and especially the head of each house (usually the eldest able-bodied man of a house) should, by law, keep a rifle, even though the law also states that the police will offer a firearm in case of need.[88] Andorra is a full member of the United Nations (UN), the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), and has a special agreement with the European Union (EU).

Military

Andorra has a small army, which has historically been raised or reconstituted at various dates, but has never in modern times amounted to a standing army. The basic principle of Andorran defence is that all able-bodied men are available to fight if called upon by the sounding of the Sometent. Being a landlocked country, Andorra has no navy.

Prior to World War I Andorra maintained an armed force of about 600 part-time militiamen. This body was not liable for service outside the principality and was commanded by two officials (viguiers) appointed by France and the Bishop of Urgell.[63]

Despite not being involved in any fighting during the First World War, Andorra was technically the longest combatant, as the country was left out of the Versailles Peace Conference, technically remaining at war with Germany from its original declaration of war in 1914 until 24 September 1958 when Andorra officially declared peace with Germany.[85][89]

In the modern era, the army has consisted of a very small body of volunteers willing to undertake ceremonial duties. Uniforms were handed down from generation to generation within families and communities.

The army's role in internal security was largely taken over by the formation of the Police Corps of Andorra in 1931. Brief civil disorder associated with the elections of 1933 led to assistance being sought from the French National Gendarmerie, with a detachment resident in Andorra for two months under the command of René-Jules Baulard.[90] The Andorran Army was reformed in the following year, with eleven soldiers appointed to supervisory roles.[91] The force consisted of six Corporals, one for each parish (although there are currently seven parishes, there were only six until 1978), plus four junior staff officers to co-ordinate action, and a commander with the rank of major. It was the responsibility of the six corporals, each in his own parish, to be able to raise a fighting force from among the able-bodied men of the parish.

Today a small, twelve-man ceremonial unit remains the only permanent section of the Andorran Army, but all able-bodied men remain technically available for military service,[92] with a requirement for each family to have access to a firearm. The army has not fought for more than 700 years, and its main responsibility is to present the flag of Andorra at official ceremonial functions.[93][94] According to Marc Forné Molné, Andorra's military budget is strictly from voluntary donations, and the availability of full-time volunteers.[95]

The myth that all members of the Andorran Army are ranked as officers is popularly maintained in many works of reference.[96][97] In reality, all those serving in the permanent ceremonial reserve hold ranks as officers, or non-commissioned officers, because the other ranks are considered to be the rest of the able-bodied male population, who may still be called upon by the Sometent to serve, although such a call has not been made in modern times.

Police Corps

Andorra maintains a small but modern and well-equipped internal police force, with around 240 police officers supported by civilian assistants. The principal services supplied by the corps are uniformed community policing, criminal detection, border control, and traffic policing. There are also small specialist units including police dogs, mountain rescue, and a bomb disposal team.[98]

GIPA

The Grup d'Intervenció Policia d'Andorra (GIPA) is a small special forces unit trained in counter-terrorism, and hostage recovery tasks. Although it is the closest in style to an active military force, it is part of the Police Corps, and not the army. As terrorist and hostage situations are a rare threat to the nation, the GIPA is commonly assigned to prisoner escort duties, and at other times to routine policing.[99]

Fire brigade

The Andorran Fire Brigade, with headquarters at Santa Coloma, operates from four modern fire stations, and has a staff of around 120 firefighters. The service is equipped with 16 heavy appliances (fire tenders, turntable ladders, and specialist four-wheel drive vehicles), four light support vehicles (cars and vans) and four ambulances.[100]

Historically, the families of the six ancient parishes of Andorra maintained local arrangements to assist each other in fighting fires. The first fire pump purchased by the government was acquired in 1943. Serious fires which lasted for two days in December 1959 led to calls for a permanent fire service, and the Andorran Fire Brigade was formed on 21 April 1961.[101]

The fire service maintains full-time cover with five fire crews on duty at any time – two at the brigade's headquarters in Santa Coloma, and one crew at each of the other three fire stations.[102]

Geography

Parishes

Andorra consists of seven parishes:

Physical geography

Due to its location in the eastern Pyrenees mountain range, Andorra consists predominantly of rugged mountains, the highest being the Coma Pedrosa at 2,942 metres (9,652 ft), and the average elevation of Andorra is 1,996 metres (6,549 ft).[103] These are dissected by three narrow valleys in a Y shape that combine into one as the main stream, the Gran Valira river, leaves the country for Spain (at Andorra's lowest point of 840 m or 2,756 ft). Andorra's land area is 468 km2 (181 sq mi).

Phytogeographically, Andorra belongs to the Atlantic European province of the Circumboreal Region within the Boreal Kingdom. According to the WWF, the territory of Andorra belongs to the ecoregion of Pyrenees conifer and mixed forests.

Climate

Andorra has an alpine climate and continental climate. Its higher elevation means there is, on average, more snow in winter, lower humidity, and it is slightly cooler in summer.

Economy

Tourism, the mainstay of Andorra's tiny, well-to-do economy, accounts for roughly 80% of GDP. An estimated 10.2 million tourists visit annually,[9] attracted by Andorra's duty-free status and by its summer and winter resorts.

One of the main sources of income in Andorra is tourism from ski resorts which total over 175 km (109 mi) of ski ground. The sport brings in over 7 million visitors and an estimated 340 million euros per year, sustaining 2,000 direct and 10,000 indirect jobs at present.

The banking sector, with its tax haven status, also contributes substantially to the economy (the financial and insurance sector accounts for approximately 19% of GDP[104]). The financial system comprises five banking groups,[105] one specialised credit entity, 8 investment undertaking management entities, 3 asset management companies and 29 insurance companies, 14 of which are branches of foreign insurance companies authorised to operate in the principality.[104]

Agricultural production is limited—only 2% of the land is arable—and most food has to be imported. Some tobacco is grown locally. The principal livestock activity is domestic sheep raising. Manufacturing output consists mainly of cigarettes, cigars, and furniture. Andorra's natural resources include hydroelectric power, mineral water, timber, iron ore, and lead.[1]

Andorra is not a member of the European Union, but enjoys a special relationship with it, such as being treated as an EU member for trade in manufactured goods (no tariffs) and as a non-EU member for agricultural products. Andorra lacked a currency of its own and used both the French franc and the Spanish peseta in banking transactions until 31 December 1999, when both currencies were replaced by the EU's single currency, the euro. Coins and notes of both the franc and the peseta remained legal tender in Andorra until 31 December 2002. Andorra negotiated to issue its own euro coins, beginning in 2014.

Andorra has traditionally had one of the world's lowest unemployment rates. In 2009 it stood at 2.9%.[106]

Andorra has long benefited from its status as a tax haven, with revenues raised exclusively through import tariffs. However, during the European sovereign-debt crisis of the 21st century, its tourist economy suffered a decline, partly caused by a drop in the prices of goods in Spain, which undercut Andorran duty-free shopping. This led to a growth in unemployment. On 1 January 2012, a business tax of 10% was introduced,[107] followed by a sales tax of 2% a year later, which raised just over 14 million euros in its first quarter.[108] On 31 May 2013, it was announced that Andorra intended to legislate for the introduction of an income tax by the end of June, against a background of increasing dissatisfaction with the existence of tax havens among EU members.[109] The announcement was made following a meeting in Paris between the Head of Government Antoni Marti and the French President and Prince of Andorra, François Hollande. Hollande welcomed the move as part of a process of Andorra "bringing its taxation in line with international standards".[110]

Demographics

Population

The population of Andorra is estimated at 85,458 (2014).[1] The population has grown from 5,000 in 1900.

Two-thirds of residents lack Andorran nationality and do not have the right to vote in communal elections. Moreover, they are not allowed to be elected as president or to own more than 33% of the capital stock of a privately held company.[111][112][113][114]

Languages

The historic and official language is Catalan, a Romance language. The Andorran government encourages the use of Catalan. It funds a Commission for Catalan Toponymy in Andorra (Catalan: la Comissió de Toponímia d'Andorra), and provides free Catalan classes to assist immigrants. Andorran television and radio stations use Catalan.

Because of immigration, historical links, and close geographic proximity, Spanish, Portuguese and French are also commonly spoken. Most Andorran residents can speak one or more of these, in addition to Catalan. English is less commonly spoken among the general population, though it is understood to varying degrees in the major tourist resorts. Andorra is one of only four European countries (together with France, Monaco, and Turkey)[115] that have never signed the Council of Europe Framework Convention on National Minorities.[116]

According to the Observatori Social d'Andorra, the linguistic usage in Andorra is as follows:[117]

| Mother tongue | % |

|---|---|

| Catalan | 38.8% |

| Spanish | 35.4% |

| Portuguese | 15% |

| French | 5.4% |

| Others | 5.5% |

| 2005 3 PoliticaLinguistica.pdf | |

Religion

The population of Andorra is predominantly (88.2%) Catholic.[118] Their patron saint is Our Lady of Meritxell. Though it is not an official state religion, the constitution acknowledges a special relationship with the Catholic Church, offering some special privileges to that group. Other Christian denominations include the Anglican Church, the Unification Church, the New Apostolic Church, and Jehovah's Witnesses. The small Muslim community is primarily made up of North African immigrants.[119] There is a small community of Hindus and Bahá'ís[120][121] and roughly 100 Jews live in Andorra.[122] (See History of the Jews in Andorra.)

Statistics

Largest cities

| | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Name | Parishes of Andorra | Pop. | ||||||

| Andorra la Vella |

1 | Andorra la Vella | Andorra la Vella | 22,256 |  Encamp  Sant Julià de Lòria | ||||

| 2 | Escaldes-Engordany | Escaldes-Engordany | 14,395 | ||||||

| 3 | Encamp | Encamp | 13,521 | ||||||

| 4 | Sant Julià de Lòria | Sant Julià de Lòria | 7,518 | ||||||

| 5 | La Massana | La Massana | 4,987 | ||||||

| 6 | Santa Coloma | Andorra la Vella | 2,937 | ||||||

| 7 | Ordino | Ordino | 2,780 | ||||||

| 8 | El Pas de la Casa | Encamp | 2,613 | ||||||

| 9 | Canillo | Canillo | 2,025 | ||||||

| 10 | Arinsal | La Massana | 1,555 | ||||||

Education

Schools

Children between the ages of 6 and 16 are required by law to have full-time education. Education up to secondary level is provided free of charge by the government.

There are three systems of school—Andorran, French, and Spanish—which use Catalan, French, and Spanish, respectively, as the main language of instruction. Parents may choose which system their children attend. All schools are built and maintained by Andorran authorities, but teachers in the French and Spanish schools are paid for the most part by France and Spain. About 50% of Andorran children attend the French primary schools, and the rest attend Spanish or Andorran schools.

University of Andorra

The Universitat d'Andorra (UdA) is the state public university and is the only university in Andorra. It was established in 1997. The university provides first-level degrees in nursing, computer science, business administration, and educational sciences, in addition to higher professional education courses. The only two graduate schools in Andorra are the Nursing School and the School of Computer Science, the latter having a PhD programme.

Virtual Studies Centre

The geographical complexity of the country as well as the small number of students prevents the University of Andorra from developing a full academic programme, and it serves principally as a centre for virtual studies, connected to Spanish and French universities. The Virtual Studies Centre (Centre d’Estudis Virtuals) at the University runs approximately twenty different academic degrees at both undergraduate and postgraduate levels in fields including tourism, law, Catalan philology, humanities, psychology, political sciences, audiovisual communication, telecommunications engineering, and East Asia studies. The Centre also runs various postgraduate programmes and continuing-education courses for professionals.

Healthcare

Healthcare in Andorra is provided to all employed persons and their families by the government-run social security system, Caixa Andorrana de Seguretat Social (CASS), which is funded by employer and employee contributions in respect of salaries.[123] The cost of healthcare is covered by CASS at rates of 75% for out-patient expenses such as medicines and hospital visits, 90% for hospitalisation, and 100% for work-related accidents. The remainder of the costs may be covered by private health insurance. Other residents and tourists require full private health insurance.[123]

The main hospital, Meritxell, is in Escaldes-Engordany.[124] There are also 12 primary health care centres in various locations around the principality.[124]

Transport

Until the 20th century, Andorra had very limited transport links to the outside world, and development of the country was affected by its physical isolation. Even now, the nearest major airports at Toulouse and Barcelona are both three hours' drive from Andorra.

Andorra has a road network of 279 km (173 mi), of which 76 km (47 mi) is unpaved. The two main roads out of Andorra la Vella are the CG-1 to the Spanish border, and the CG-2 to the French border via the Envalira Tunnel near El Pas de la Casa.[125] Bus services cover all metropolitan areas and many rural communities, with services on most major routes running half-hourly or more frequently during peak travel times. There are frequent long-distance bus services from Andorra to Barcelona and Toulouse, plus a daily tour from the former city. Bus services are mostly run by private companies, but some local ones are operated by the government.

There are no airports for fixed-wing aircraft within Andorra's borders but there are, however, heliports in La Massana (Camí Heliport), Arinsal and Escaldes-Engordany with commercial helicopter services[126][127] and an airport located in the neighbouring Spanish comarca of Alt Urgell, 12 kilometres (7.5 miles) south of the Andorran-Spanish border.[128] Since July 2015, Andorra–La Seu d'Urgell Airport has operated commercial flights to Madrid and Palma de Mallorca, and is the main hub for Air Andorra and Andorra Airlines.

Nearby airports located in Spain and France provide access to international flights for the principality. The nearest airports are at Perpignan, France (156 kilometres or 97 miles from Andorra) and Lleida, Spain (160 kilometres or 99 miles from Andorra). The largest nearby airports are at Toulouse, France (165 kilometres or 103 miles from Andorra) and Barcelona, Spain (215 kilometres or 134 miles from Andorra). There are hourly bus services from both Barcelona and Toulouse airports to Andorra.

The nearest railway station is L'Hospitalet-près-l'Andorre 10 km (6 mi) east of Andorra which is on the 1,435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in)-gauge line from Latour-de-Carol (25 km or 16 mi) southeast of Andorra, to Toulouse and on to Paris by the French high-speed trains. This line is operated by the SNCF. Latour-de-Carol has a scenic 1,000 mm (3 ft 3 3⁄8 in) metre gauge trainline to Villefranche-de-Conflent, as well as the SNCF's 1,435 mm gauge line connecting to Perpignan, and the RENFE's 1,668 mm (5 ft 5 21⁄32 in) -gauge line to Barcelona.[129][130] There are also direct Intercités de Nuit trains between L'Hospitalet-près-l'Andorre and Paris on certain dates.[131]

Media and telecommunications

In Andorra, mobile and fixed telephone and internet services are operated exclusively by the Andorran national telecommunications company, SOM, also known as Andorra Telecom (STA). The same company also manages the technical infrastructure for national broadcasting of digital television and radio.

By the end of 2010, it was planned that every home in the country would have fibre-to-the-home for internet access at a minimum speed of 100 Mbit/s,[132] and the availability was complete in June 2012.

There is only one Andorran television station, Ràdio i Televisió d'Andorra (RTVA). Radio Nacional d’Andorra operates two radio stations, Radio Andorra and Andorra Música. There are three national newspapers, Diari d'Andorra, El Periòdic d'Andorra, and Bondia as well as several local newspapers. There is also an amateur radio society.[133] Additional TV and radio stations from Spain and France are available via digital terrestrial television and IPTV.

Culture

The official and historic language is Catalan. Thus the culture is Catalan, with its own specificity.

Andorra is home to folk dances like the contrapàs and marratxa, which survive in Sant Julià de Lòria especially. Andorran folk music has similarities to the music of its neighbours, but is especially Catalan in character, especially in the presence of dances such as the sardana. Other Andorran folk dances include contrapàs in Andorra la Vella and Saint Anne's dance in Escaldes-Engordany. Andorra's national holiday is Our Lady of Meritxell Day, 8 September.[1] American folk artist Malvina Reynolds, intrigued by its defence budget of $4.90, wrote a song "Andorra". Pete Seeger added verses, and sang "Andorra" on his 1962 album The Bitter and the Sweet.

Sports

Andorra is famous for the practice of Winter Sports. Popular sports played in Andorra include football, rugby union, basketball and roller hockey.

In roller hockey Andorra usually plays in CERH Euro Cup and in FIRS Roller Hockey World Cup. In 2011, Andorra was the host country to the 2011 European League Final Eight.

The country is represented in association football by the Andorra national football team. However, the team has had little success internationally because of Andorra's small population.[134] Football is ruled in Andorra by the Andorran Football Federation founded in 1994, it organizes the national competitions of association football (Primera Divisió, Copa Constitució and Supercopa) and futsal. FC Andorra, a club based in Andorra la Vella founded in 1942, compete in the Spanish football league system.

Rugby is a traditional sport in Andorra, mainly influenced by the popularity in southern France. The Andorra national rugby union team, nicknamed "Els Isards", has impressed on the international stage in rugby union and rugby sevens.[135] VPC Andorra XV is a rugby team based in Andorra la Vella actually playing in the French championship.

Basketball popularity has increased in the country since the 1990s, when the Andorran team BC Andorra played in the top league of Spain (Liga ACB).[136] After 18 years the club returned to the top league in 2014.[137]

Other sports practised in Andorra include cycling, volleyball, judo, Australian Rules football, handball, swimming, gymnastics, tennis and motorsports. In 2012, Andorra raised its first national cricket team and played a home match against the Dutch Fellowship of Fairly Odd Places Cricket Club, the first match played in the history of Andorra at an altitude of 1,300 metres (4,300 ft).[138]

Andorra first participated at the Olympic Games in 1976. The country has also appeared in every Winter Olympic Games since 1976. Andorra competes in the Games of the Small States of Europe being twice the host country in 1991 and 2005.

As part of the Catalan cultural ambit, Andorra is home to a team of castellers, or Catalan human tower builders. The Castellers d'Andorra, based in the town of Santa Coloma d'Andorra, are recognized by the Coordinadora de Colles Castelleres de Catalunya, the governing body of castells.

Major achievements

Ariadna Tudel Cuberes and Sophie Dusautoir Bertrand earned the bronze medal in the women's team competition at the 2009 European Championship of Ski Mountaineering. Joan Verdu Sanchez earned a bronze medal in Alpine Skiing at the 2012 Winter Youth Olympics. In 2015, Marc Oliveras earned a silver medal in Alpine Skiing at the 2015 Winter Universiade, while Carmina Pallas earned a silver and a bronze medal in the same competition.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "CIA World Factbook entry: Andorra". Cia.gov. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- ↑ http://data.un.org/CountryProfile.aspx?crName=Andorra

- ↑

- ↑ "HUMAN DEVELOPMENT REPORT 2016 – Statistical annex". United Nations. 2016. Retrieved 25 March 2017.

- ↑ Funk and Wagnalls Encyclopedia, 1993

- ↑ Malankar, Nikhil (2017-04-18). "Andorra: 10 Unusual Facts About The Tiny European Principality". Tell Me Nothing. Retrieved 2017-06-13.

- ↑ "Maps, Weather, and Airports for Andorra la Vella, Andorra". Fallingrain.com. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- ↑ "Background Note: Andorra". State.gov. Retrieved 2015-05-14.

- 1 2 "HOTELERIA I TURISME". Retrieved 14 May 2015.

- ↑ "United Nations Member States". Un.org. Retrieved 2015-05-14.

- ↑ GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death, Collaborators. (10 January 2015). "Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013.". Lancet (London, England). 385 (9963): 117–71. PMC 4340604

. PMID 25530442. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2.

. PMID 25530442. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2. - ↑ Diccionari d'Història de Catalunya; ed. 62; Barcelona; 1998; ISBN 84-297-3521-6; p. 42; entrada "Andorra"

- ↑ Font Rius, José María (1985). Estudis sobre els drets i institucions locals en la Catalunya medieval. Edicions Universitat Barcelona. p. 743. ISBN 8475281745.

- ↑ Gaston, L. L. (1912). Andorra, the Hidden Republic: Its Origin and Institutions, and the Record of a Journey Thither. New York, USA: McBridge, Nast & Co. p. 9.

- ↑ "Online Etymology Dictionary". Etymonline.com. Retrieved 2015-05-14.

- ↑ Freedman, Paul (1999). Images of the Medieval Peasant. CA, USA: Stanford University Press. p. 189. ISBN 9780804733731.

- ↑

- 1 2 Guillamet Antoni 2009, p. 32, 33.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Armengol Aleix 2009, p. 44 a 92.

- ↑ Guillamet Antoni 2009, p. 34, 35, 38, 39.

- ↑

- ↑ Guillamet Antoni 2009, p. 43.

- 1 2 Guillamet Antoni 2009, p. 37, 36.

- 1 2 Guillamet Antoni 2009, p. 44, 45, 46, 47.

- ↑ Guillamet Antoni 2009, p. 52, 53.

- 1 2 3 4 Armengol Aleix 2009.

- ↑ "El pas de Carlemany - Turisme Andorra la Vella". turisme.andorralavella.ad. Retrieved 3 August 2017.

- ↑ Vidal, Jaume. "Andorra mira els arxius". Elpuntavui.cat. Retrieved 3 August 2017.

- ↑ "La formació d'Andorra". Gran Enciclopèdia Catalana. Enciclopèdia Catalana. (in Catalan) English version

- 1 2 3 "Elements de la història del Principat d'Andorra" (in Catalan). Archived from the original on 9 February 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 Armengol Aleix 2009, p. 96 a 146.

- ↑ "Ermessenda de Castellbò". Gran Enciclopèdia Catalana. Enciclopèdia Catalana. (in Catalan) English version

- 1 2 Guillamet Anton 2009.

- 1 2 Jordi Planellas 2013.

- ↑ "Absis d'Engolasters - Museu Nacional d'Art de Catalunya". www.museunacional.cat. Retrieved 3 August 2017.

- ↑ Guillamet Anton 2009, p. 60, 61.

- ↑ Guillamet Antoni 2009, p. 78, 79, 80, 81, 88, 89.

- ↑ Guillamet Antoni 2009, p. 48, 49,.

- ↑ Garcia 2011.

- ↑ Armengol Aleix 2009, p. 150 a 194.

- ↑ "HISTÒRIA DE LA LLENGUA CATALANA" (PDF). Racocatala.cat. Retrieved 2017-08-03.

- ↑ Anne Doustaly-Dunyach 2011.

- 1 2 Llop Rovira 1998, p. 44, 45, 47, 48, 50.

- ↑ Guillamet Anton 2009, p. 108, 109.

- 1 2 Armengol Aleix 2009, p. 238, 239.

- ↑ Jordi Planellas 2013, p. 42.

- ↑ Llop Rovira 1998, p. 53, 54, 56.

- ↑ Llop Rovira 1998, p. 14.

- ↑ Llop Rovira 1998, p. 15.

- ↑ Guillamet Anton 2009, p. 134.

- ↑

- ↑ Llop Rovira 1998, p. 20, 21.

- ↑ Guillamet Antoni 2009, p. 106, 107.

- ↑ Guillamet Anton 2009, p. 105, 106, 107, 140, 141.

- ↑ Armengol Aleix 2009, p. 263 a 270.

- ↑ Llop Rovira 1998, p. 60.

- ↑ Guillamet Antoni 2009, p. 82.

- 1 2 3 Armengol Aleix 2009, p. 229.

- ↑ Llop Rovira 1998, p. 49 a 52, i 57, 58.

- ↑ Armengol Aleix 2009, p. 172.

- ↑ Guillamet Anton 2009, p. 172.

- ↑ Armengol Aleix 2009, p. 342, 343.

- 1 2 Page 966, Volume 1, Encyclopædia Britannica, Eleventh Edition 1910–1911

- ↑ Armengol Aleix 2009, p. 192, 193.

- ↑ Guillamet Anton 2009, p. 191, 192, 193.

- ↑ Armengol Aleix 2009, p. 345 a 347.

- ↑ Segalàs 2012, p. 93 a 95.

- ↑ "Saqueo de Canillo por las fuerzas del gobierno revolucionario tras el sitio de la aldea". Wdl.org. 12 March 1881. Retrieved 3 August 2017.

- ↑ Armengol Aleix 2009, p. 198, 199, 203.

- ↑ Peruga Guerrero 1998, p. 59, 60, 63.

- ↑ Ministeri d'Educació, Joventut i Esports 1996, p. 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65.

- ↑ Armengol Aleix 2009, p. 194, 195.

- ↑ Guillamet Anton 2009, p. 194, 195.

- ↑ Armengol Aleix 2009, p. 348 a 350.

- ↑ Segalàs 2012, p. 95.

- ↑ Peruga Guerrero 1998, p. 64, 65, 66, 67, 68.

- ↑ Ministeri d'Educació, Joventut i Esports 1996, p. 67 a 70.

- ↑ Guillamet Anton 2009, p. 198, 199, 202, 203.

- ↑ Armengol Aleix 2009, p. 352, 353.

- ↑ Peruga Guerrero 1998, p. 78, 79, 80, 81.

- ↑ Ministeri d'Educació, Joventut i Esports 1996, p. 74.

- ↑ Armengol Aleix 2009, p. 354, 355, 356, 357.

- ↑ Àrea de Recerca Històrica del Govern d'Andorra 2006, p. 33.

- ↑ Segalàs 2012.

- 1 2 "World War I Ends in Andorra". New York Times. 25 September 1958. p. 66.

- ↑ "Documento BOE-A-1993-16868". BOE.es. 30 June 1993. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- ↑ "El Sometent | Tourism". Turisme.andorralavella.ad. 17 May 2011. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- 1 2 "Decret veguers Sometent, del 23 d'octubre de 1984" (PDF). Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- ↑ Reich, Herb (2012). Lies They Teach in School: Exposing the Myths Behind 250 Commonly Believed Fallacies. New York: Skyhorse Publishing, Inc. p. 52. ISBN 9781620873458.

- ↑ Ben Cahoon. "Andorra". Worldstatesmen.org. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- ↑ "Andorra's 'ARMY' – Eleven Permanent Troops!". The Times. 5 January 1934. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- ↑ "Andorra". State.gov. 20 April 2012. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- ↑ "Bop14073" (PDF). Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- ↑ "History of the Principality of Andorra". Andorramania.com. 11 December 1997. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- ↑ "Andorra". Un.org. 25 September 2003. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- ↑ "Andorra". State.gov. 2013-09-13. Retrieved 2015-05-14.

- ↑ "Andorra Politics, government, and taxation, Information about Politics, government, and taxation in Andorra". Nationsencyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2015-05-14.

- ↑ Carles Iglesias Carril. "Andorran Police Service website". Policia.ad. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- ↑ Carles Iglesias Carril. "Cos de Policia – Estructura organitzativa". Policia.ad. Retrieved 2015-05-14.

- ↑ "Vehicle details with extensive photo gallery here". Bombers.ad. Archived from the original on 22 July 2012. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- ↑ "Fire Brigade history here (in Catalan)". Bombers.ad. Archived from the original on August 1, 2012. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- ↑ "Andorran Fire Service site". Bombers.ad. 17 August 2012. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- ↑ Atlas of Andorra (1991), Andorran Government. OCLC 801960401. (in Catalan)

- 1 2 "Andorra and its financial system 2013" (PDF). Aba.ad. Retrieved 14 May 2015.

- ↑ "List of Banks in Andorra". Thebanks.eu. Retrieved 2015-05-14.

- ↑ "CIA World Factbook: Andorra". Retrieved 5 June 2013.

- ↑ "Andorra gets a taste of taxation". The guardian. 27 December 2011. Retrieved 30 March 2013.

- ↑ "Andorra Unveils First Indirect Tax Revenue Figures". Tax News. 9 May 2013.

- ↑ "Andorra to introduce income tax for first time". BBC News. 2 June 2013.

- ↑ "Andorre aligne progressivement sa fiscalité sur les standards internationaux (Elysée)". Notre Temps. 31 May 2011.

- ↑ "El Parlamento andorrano facilita a los hijos de los residentes la adquisición de la nacionalidad | Edición impresa | EL PAÍS". Elpais.com. Retrieved 2015-05-14.

- ↑ "Un examen para ser andorrano | Edición impresa | EL PAÍS". Elpais.com. 1985-10-27. Retrieved 2015-05-14.

- ↑ "La Constitución de Andorra seguirá limitando los derechos del 70% de la población | Edición impresa | EL PAÍS". Elpais.com. 1992-05-09. Retrieved 2015-05-14.

- ↑ "Andorra, sólo inmigrantes sanos | Edición impresa | EL PAÍS". Elpais.com. 2006-07-14. Retrieved 2015-05-14.

- ↑ "Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities (FCNM) : National Minorities, ''Council of Europe'', 14 September 2010". Coe.int. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- ↑ "Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities CETS No. 157". Conventions.coe.int. Retrieved 25 November 2012.

- ↑ "Observatori de l'Institut d'Estudis Andorrans" (in Catalan). Archived from the original on 17 July 2007. Retrieved 5 June 2013.

- ↑ PEW 2011. Pewforum.org (2011-12-19). Retrieved on 2015-12-30.

- ↑ "Andorra facts". Encyclopedia.com. Encyclopedia.com. Retrieved November 22, 2016.

- ↑ "Andorra". International – Regions – Southern Europe. The Association of Religion Data Archives. 2005. Retrieved 4 July 2009.

- ↑ "Andorra: population, capital, cities, GDP, map, flag, currency, languages, ...". Wolfram Alpha. Online. Wolfram – Alpha (curated data). 13 March 2010. Archived from the original on 2012-03-08.

- ↑ "US Dept of State information". State.gov. 8 November 2005. Retrieved 9 August 2013.

- 1 2 Travailler en Andorre (May 2006), Govern d'Andorra, Servei d'Ocupació, p.30. (in French)

- 1 2 "List of specialties with coverage by CASS at the Hospital Nostra Senyora de Meritxell (2009)". Online.cass.ad. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- ↑ "Agència de Mobilitat, Govern d'Andorra". Mobilitat.ad. Archived from the original on 2013-03-17.

- ↑ "Inici – Heliand – Helicopters a Andorra". Heliand. Retrieved 2015-05-14.

- ↑ Archived 15 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Public and regional airport of Andorra-la Seu d’Urgell".

- ↑ "Sncf Map" (in German). Bueker.net. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- ↑ "Google map". Maplandia.com. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- ↑ "How to travel by train from London to Andorra".

- ↑ SOM Newsletter, March 2009.

- ↑ Unió de Radioaficionats Andorra. Ura.ad. Retrieved on 2015-12-30.

- ↑ "FIFA Rankings – Andorra". Fifa.com. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- ↑ Archived 22 May 2014 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "El BC Andorra quiere volver a la Liga más bella". MARCA.com. Retrieved 2015-05-14.

- ↑ "El River Andorra regresa a la ACB 18 años después | Baloncesto | EL MUNDO". Elmundo.es. 2014-03-22. Retrieved 2015-05-14.

- ↑ "Netherlands Based FFOP CC Beats Andorra National Team". Cricket World. 3 September 2012. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

External links

| The Wikibook Wikijunior:Countries A-Z has a page on the topic of: Andorra |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Govern d'Andorra – Official governmental site (in Catalan)

- "Andorra". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency.

- Portals to the World from the United States Library of Congress

- Andorra from UCB Libraries GovPubs

- Andorra at DMOZ

- Andorra from the BBC News

- Andorra – Guía, turismo y de viajes

- History of Andorra: Primary Documents from EuroDocs

- A New Path for Andorra – slideshow by The New York Times

-

Geographic data related to Andorra at OpenStreetMap

Geographic data related to Andorra at OpenStreetMap -

Wikimedia Atlas of Andorra

Wikimedia Atlas of Andorra

.svg.png)