Vajrayana

| Part of a series on |

| Vajrayana Buddhism |

|---|

|

|

Traditions Historical traditions:

New branches:

|

|

History |

|

Pursuit |

|

Practices |

|

Festivals |

|

Ordination and transmission |

| Vajrayana Buddhism portal |

Vajrayāna, Mantrayāna, Esoteric Buddhism and Tantric Buddhism refer to the Buddhist tradition of Tantra, an esoteric system of beliefs and practices that developed in medieval India.

Vajrayāna is usually translated as Diamond Vehicle or Thunderbolt Vehicle, referring to the Vajra, a mythical weapon which is also used as a ritual implement.

According to Vajrayāna scriptures, the term Vajrayāna refers to one of three vehicles or routes to enlightenment, the other two being the Śrāvakayāna (also known as the Hīnayāna) and Mahāyāna.

Founded by Indian Mahāsiddhas, Vajrayāna subscribes to the literature known as the Buddhist Tantras.[1]

History of Vajrayāna in India

Siddha movement

Elements of Tantric Buddhism can be traced back to groups of wandering yogis called mahasiddhas (great adepts).[2] According to Reynolds (2007), the mahasiddhas date to the medieval period in North India (3–13 cen. CE), and used methods that were radically different than those used in Buddhist monasteries including living in forests and caves and practiced meditation in charnel grounds similar to those practiced by Shaiva Kapalika ascetics.[3] These yogic circles came together in tantric feasts (ganachakra) often in sacred sites (pitha) and places (ksetra) which included dancing, singing, sex rites and the ingestion of taboo substances like alcohol, urine, meat, etc.[4] It is interesting to note that at least two of the Mahasiddhas given in the Buddhist literature are actually names for Shaiva Nath saints (Gorakshanath and Matsyendranath) who practiced Hatha Yoga.

According to Schumann, a movement called Sahaja-siddhi developed in the 8th century in Bengal.[5] It was dominated by long-haired, wandering yogis called mahasiddhas who openly challenged and ridiculed the Buddhist establishment.[6] The Mahasiddhas pursued siddhis, magical powers such as flight and Extrasensory perception as well as liberation.[7]

Tantras

Earlier Mahayana sutras already contained some elements which are emphasized in the Tantras, such as mantras and dharani.[8] The use of mantras and protective verses actually dates back to the Vedic period and the early Buddhist texts like the Pali canon. The practice of visualization of Buddhas such as Amitabha is also seen in pre-tantra texts like the Longer Sukhāvatīvyūha Sūtra.[9] There are other Mahayana sutras which contain "proto-tantric" material such as the Gandavyuha sutra and the Dasabhumika which might have served as a central source of visual imagery for Tantric texts.[10]

Vajrayana developed a large corpus of texts called the Buddhist Tantras, some of which can be traced to at least the 7th century CE but might be older. The dating of the tantras is "a difficult, indeed an impossible task" according to David Snellgrove.[11] Some of the earliest of these texts, kriya tantras such as the Mañjuśrī-mūla-kalpa (6th century), focus on the use of mantras and dharanis for mostly worldly ends including curing illness, controlling the weather and generating wealth.[12]

The Tattvasaṃgraha Tantra, classed as a "Yoga tantra", is one of the first Buddhist tantras which focuses on liberation as opposed to worldly goals and in the Vajrasekhara Tantra the concept of the five Buddha families is developed.[13] Other early tantras include the Mahavairocana Tantra and the Guhyasamāja Tantra.[14] The Guhyasamāja is a Mahayoga class of Tantra, which features new forms of ritual practice considered "left-hand" (vamachara) such as the use taboo substances like alcohol, sexual yoga, and charnel ground practices which evoke wrathful deities.[15] Indeed, Ryujun Tajima divides the tantras into those which were "a development of Mahayanist thought" and those "formed in a rather popular mould toward the end of the eighth century and declining into the esoterism of the left",[16] mainly, the Yogini tantras and later works associated with wandering antinomian yogis. Later monastic Vajrayana Buddhists reinterpreted and internalized these radically transgressive and taboo practices as metaphors and visualization exercises.

Later tantras such as such as the Hevajra Tantra and the Chakrasamvara are classed as "Yogini tantras" and represent the final form of development of Indian Buddhist tantras in the ninth and tenth centuries.[17] The Kalachakra tantra developed in the 10th century.[18] It is farthest removed from the earlier Buddhist traditions, and incorporates concepts of messianism and astrology not present elsewhere in Buddhist literature.[6]

According to Ronald M. Davidson, the rise of Tantric Buddhism was a response to the feudal structure of Indian society in the early medieval period (ca. 500-1200 CE) which saw kings being divinized as manifestations of gods. Likewise, tantric yogis reconfigured their practice through the metaphor of being consecrated (abhiśeka) as the overlord (rājādhirāja) of a mandala palace of divine vassals, an imperial metaphor symbolizing kingly fortresses and their political power.[19]

Influence of Saivism

Various classes of Vajrayana literature developed as a result of royal courts sponsoring both Buddhism and Saivism.[20] The Mañjusrimulakalpa, which later came to be classified under Kriyatantra, states that mantras taught in the Shaiva, Garuda and Vaishnava tantras will be effective if applied by Buddhists since they were all taught originally by Manjushri.[21]

According to Alexis Sanderson, the Vajrayana Yogini-tantras draw extensively from Shaiva Bhairava tantras classified as Vidyapitha. A comparison of them shows similarity in "ritual procedures, style of observance, deities, mantras, mandalas, ritual dress, Kapalika accoutrements, specialized terminology, secret gestures, and secret jargons. There is even direct borrowing of passages from Saiva texts."[22]

The Guhyasiddhi of Padmavajra, a work associated with the Guhyasamaja tradition, prescribes acting as a Shaiva guru and initiating members into Saiva Siddhanta scriptures and mandalas.[23] The Samvara tantra texts adopted the pitha list from the Shaiva text Tantrasadbhava, introducing a copying error where a deity was mistaken for a place.[24]

Philosophical background

According to Louis de La Vallée-Poussin and Alex Wayman, the view of the Vajrayana is based on Mahayana Buddhist philosophy, mainly the Madhyamaka and Yogacara schools.[25][26] The major difference seen by Vajrayana thinkers is Tantra's superiority due to being a faster vehicle to liberation containing many skillful methods (upaya) of tantric ritual.

The importance of the theory of emptiness is central to the Tantric view and practice. Buddhist emptiness sees the world as being fluid, without an ontological foundation or inherent existence but ultimately a fabric of constructions. Because of this, tantric practice such as self-visualization as the deity is seen as being no less real than everyday reality, but a process of transforming reality itself, including the practitioner's identity as the deity. As Stephan Beyer notes, "In a universe where all events dissolve ontologically into Emptiness, the touching of Emptiness in the ritual is the re-creation of the world in actuality".[27]

The doctrine of Buddha-nature, as outlined in the Ratnagotravibhāga of Asanga, was also an important theory which became the basis for Tantric views.[28] As explained by the Tantric commentator Lilavajra, this "intrinsic secret (behind) diverse manifestation" is the utmost secret and aim of Tantra. According to Alex Wayman this "Buddha embryo" (tathāgatagarbha) is a "non-dual, self-originated Wisdom (jnana), an effortless fount of good qualities" that resides in the mindstream but is "obscured by discursive thought."[29]

Another fundamental theory of Tantric practice is that of transformation. Negative mental factors such as desire, hatred, greed, pride are not rejected as in non Tantric Buddhism, but are used as part of the path. As noted by French Indologist Madeleine Biardeau, tantric doctrine is "an attempt to place kama, desire, in every meaning of the word, in the service of liberation."[30] This view is outlined in the following quote from the Hevajra tantra:

Those things by which evil men are bound, others turn into means and gain thereby release from the bonds of existence. By passion the world is bound, by passion too it is released, but by heretical Buddhists this practice of reversals is not known.[31]

The Hevajra further states that "One knowing the nature of poison may dispel poison with poison."[32] As Snellgrove notes, this idea is already present in Asanga's Mahayana-sutra-alamkara-karika and therefore it is possible that he was aware of Tantric techniques, including sexual yoga.[33]

According to Buddhist Tantra there is no strict separation of the profane or samsara and the sacred or nirvana, rather they exist in a continuum. All individuals are seen as containing the seed of enlightenment within, which is covered over by defilements. Douglas Duckworth notes that Vajrayana sees Buddhahood not as something outside or an event in the future, but as immanently present.[34]

Indian Tantric Buddhist philosophers such as Buddhaguhya, Vimalamitra, Ratnākaraśānti and Abhayakaragupta continued the tradition of Buddhist philosophy and adapted it to their commentaries on the major Tantras. Abhayakaragupta’s Vajravali is a key source in the theory and practice of tantric rituals. After monks such as Vajrabodhi and Śubhakarasiṃha brought Tantra to Tang China (716 to 720), tantric philosophy continued to be developed in Chinese and Japanese by thinkers such as Yi Xing and Kūkai.

Likewise in Tibet, Sakya Pandita (1182-28 - 1251), as well as later thinkers like Longchenpa (1308–1364) expanded on these philosophies in their Tantric commentaries and treatises. The status of the tantric view continued to be debated in medieval Tibet. Tibetan Buddhist Rongzom Chokyi Zangpo (1012–1088) held that the views of sutra such as Madhyamaka were inferior to that of tantra, as Koppl notes:

By now we have seen that Rongzom regards the views of the Sutrayana as inferior to those of Mantra, and he underscores his commitment to the purity of all phenomena by criticizing the Madhyamaka objectification of the authentic relative truth.[35]

Tsongkhapa (1357–1419) on the other hand, held that there is no difference between Vajrayana and other forms of Mahayana in terms of prajnaparamita (perfection of insight) itself, only that Vajrayana is a method which works faster.[36]

Place within Buddhist tradition

Various classifications are possible when distinguishing Vajrayana from the other Buddhist traditions. Vajrayana can be seen as a third yana, next to Hinayana and Mahayana.[6] Vajrayana can be distinguished from the Sutrayana. The Sutrayana is the method of perfecting good qualities, where the Vajrayāna is the method of taking the intended outcome of Buddhahood as the path. Vajrayana, belonging to the mantrayana, can also be distinguished from the paramitayana. According to this schema, Indian Mahayana revealed two vehicles (yana) or methods for attaining enlightenment: the method of the perfections (Paramitayana) and the method of mantra (Mantrayana).[37] The Paramitayana consists of the six or ten paramitas, of which the scriptures say that it takes three incalculable aeons to lead one to Buddhahood. The tantra literature, however, claims that the Mantrayana leads one to Buddhahood in a single lifetime.[37] According to the literature, the mantra is an easy path without the difficulties innate to the Paramitayana.[37] Mantrayana is sometimes portrayed as a method for those of inferior abilities.[37] However the practitioner of the mantra still has to adhere to the vows of the Bodhisattva.[37]

Characteristics of Vajrayana

Goal

The goal of spiritual practice within the Mahayana and Vajrayana traditions is to become a Sammāsambuddha (fully awakened Buddha), those on this path are termed Bodhisattvas. As with the Mahayana, motivation is a vital component of Vajrayana practice. The Bodhisattva-path is an integral part of the Vajrayana, which teaches that all practices are to be undertaken with the motivation to achieve Buddhahood for the benefit of all sentient beings.

In the Sutrayana practice, a path of Mahayana, the "path of the cause" is taken, whereby a practitioner starts with his or her potential Buddha-nature and nurtures it to produce the fruit of Buddhahood. In the Vajrayana the "path of the fruit" is taken whereby the practitioner takes his or her innate Buddha-nature as the means of practice. The premise is that since we innately have an enlightened mind, practicing seeing the world in terms of ultimate truth can help us to attain our full Buddha-nature.[38] Experiencing ultimate truth is said to be the purpose of all the various tantric techniques practiced in the Vajrayana.

Esoteric transmission

Vajrayana Buddhism is esoteric in the sense that the transmission of certain teachings only occurs directly from teacher to student during an empowerment (abhiṣeka) and their practice requires initiation in a ritual space containing the mandala of the deity.[39] Many techniques are also commonly said to be secret, but some Vajrayana teachers have responded that secrecy itself is not important and only a side-effect of the reality that the techniques have no validity outside the teacher-student lineage.[40] In order to engage in Vajrayana practice, a student should have received such an initiation or permission:

If these techniques are not practiced properly, practitioners may harm themselves physically and mentally. In order to avoid these dangers, the practice is kept "secret" outside the teacher/student relationship. Secrecy and the commitment of the student to the vajra guru are aspects of the samaya (Tib. damtsig), or "sacred bond", that protects both the practitioner and the integrity of the teachings."[41]

The secrecy of teachings was often protected through the use of use of allusive, indirect, symbolic and metaphorical language (twilight language) which required interpretation and guidance from a teacher.[42] The teachings may also be considered "self-secret", meaning that even if they were to be told directly to a person, that person would not necessarily understand the teachings without proper context. In this way the teachings are "secret" to the minds of those who are not following the path with more than a simple sense of curiosity.[43][44]

Because of their role in giving access to the practices and guiding the student through them, the role of the Guru, Lama or Vajracharya is indispensable in Vajrayana.

Affirmation of the feminine, antinomian and taboo

Some Vajrayana rituals include use of certain taboo substances, such as blood, semen, alcohol and urine, as ritual offerings and sacraments, though these are often replaced with less taboo substances in their place such as yogurt. Tantric feasts and initiations sometimes employed substances like human flesh as noted by Kahha’s Yogaratnamala.[45] The use of these substances is related to the non-dual (advaya) nature of Buddhahood. Since the ultimate state is in some sense non-dual, a practitioner can approach that state by "transcending attachment to dual categories such as pure and impure, permitted and forbidden". As the Guhyasamaja Tantra states "the wise man who does not discriminate achieves buddhahood".[46]

Vajrayana rituals also include sexual yoga, union with a physical consort as part of advanced practices. Some tantras go further, the Hevajra Tantra states ‘You should kill living beings, speak lying words, take what is not given, consort with the women of others’.[47] While some of these statements were taken literally as part of ritual practice, others such as killing was interpreted in a metaphorical sense. In the Hevajra, "killing" is defined as developing concentration by killing the life-breath of discursive thoughts.[48] Likewise, while actual sexual union with a physical consort is practiced, it is also common to use a visualized mental consort.

Alex Wayman points out that the symbolic meaning of tantric sexuality is ultimately rooted in bodhicitta and the bodhisattva's quest for enlightenment is likened to a lover seeking union with the mind of the Buddha.[49] Judith Simmer-Brown notes the importance of the psycho-physical experiences arising in sexual yoga, termed "great bliss" (Mahasukha): "Bliss melts the conceptual mind, heightens sensory awareness, and opens the practitioner to the naked experience of the nature of mind."[50] This tantric experience is not the same as ordinary self gratifying sexual passion since it relies on tantric meditative methods using the subtle body and visualizations as well as the motivation for enlightenment.[51] As the Hevajra tantra says:

"This practice [of sexual union with a consort] is not taught for the sake of enjoyment, but for the examination of one's own thought, whether the mind is steady or waving."[52]

Feminine deities and forces are also increasingly prominent in Vajrayana. In the Yogini tantras in particular, women and female figures are given high status as the embodiment of female deities such as the wild and nude Vajrayogini.[53] The Candamaharosana Tantra states:

- Women are heaven, women are the teaching (dharma)

- Women indeed are the highest austerity (tapas)

- Women are the Buddha, women are the Sangha

- Women are the Perfection of Wisdom.

- Candamaharosana Tantra viii:29–30[54]

In India, there is evidence to show that women participated in tantric practice alongside men and were also teachers, adepts and authors of tantric texts.[55]

Vows and behaviour

Practitioners of the Vajrayana need to abide by various tantric vows or samaya of behaviour. These are extensions of the rules of the Prātimokṣa and Bodhisattva vows for the lower levels of tantra, and are taken during initiations into the empowerment for a particular Anuttarayoga Tantra. The special tantric vows vary depending on the specific mandala practice for which the initiation is received, and also depending on the level of initiation. Ngagpas of the Nyingma school keep a special non-celibate ordination.

A tantric guru, or teacher, is expected to keep his or her samaya vows in the same way as his students. Proper conduct is considered especially necessary for a qualified Vajrayana guru. For example, the Ornament for the Essence of Manjushrikirti states:[56]

Distance yourself from Vajra Masters who are not keeping the three vows

who keep on with a root downfall, who are miserly with the Dharma,

and who engage in actions that should be forsaken.

Those who worship them go to hell and so on as a result.

Tantra techniques

While Vajrayana includes all of the traditional practices used in Mahayana Buddhism such as samatha and vipassana meditation and the paramitas, it also includes a number of unique practices or "skillful means" (Sanskrit: upaya) which are seen as more advanced and effective. Vajrayana is a system of lineages, whereby those who successfully receive an empowerment or sometimes called initiation (permission to practice) are seen to share in the mindstream of the realisation of a particular skillful means of the vajra Master. Vajrayana teaches that the Vajrayana techniques provide an accelerated path to enlightenment which is faster than other paths.[57]

A central feature of tantric practice is the use of mantras, syllables, words or a collection of syllables understood to have special powers and hence is a 'performative utterance' used for a variety of ritual ends. In tantric meditation, mantric seed syllables are used during the ritual evocation of deities which are said to arise out of the uttered and visualized mantric syllables. After the deity has been established, heart mantras are visualized as part of the contemplation in different points of the deity's body.[58]

According to Alex Wayman, Buddhist esotericism is centered on what is known as "the three mysteries" or "secrets": the tantric adept affiliates his body, speech, and mind with the body, speech, and mind of the Buddha through mudra, mantras and samadhi respectively.[59] Padmavajra (c 7th century) explains in his Tantrarthavatara Commentary, the secret Body, Speech, and Mind of the Tathagatas are:[60]

- Secret of Body: Whatever form is necessary to tame the living beings.

- Secret of Speech: Speech exactly appropriate to the lineage of the creature, as in the language of the yaksas, etc.

- Secret of Mind: Knowing all things as they really are.

Deity yoga

The fundamental, defining practice of Buddhist Tantra is “deity yoga” (devatayoga), meditation on a yidam, or personal deity, which involves the recitation of mantras, prayers and visualization of the deity along with the associated mandala of the deity's Pure Land, with consorts and attendants.[61] According to Tsongkhapa, deity yoga is what separates Tantra from sutra practice.[62]

A key element of this practice involves the dissolution of the profane world and identification with a sacred reality.[63] Because Tantra makes use of a "similitude" of the resultant state of Buddhahood as the path, it is known as the effect vehicle or result vehicle (phalayana) which "brings the effect to the path".[64]

In the Highest Yoga Tantras and in the Inner Tantras this is usually done in two stages, the generation stage (utpattikrama) and the completion stage (nispannakrama). In the generation stage, one dissolves oneself in emptiness and meditates on the yidam, resulting in identification with this yidam. In the completion stage, the visualization of and identification with the yidam is dissolved in the realization of luminous emptiness. Ratnakarasanti describes the generation stage cultivation practice thus:

[A]ll phenomenal appearance having arisen as mind, this very mind is [understood to be] produced by a mistake (bhrāntyā), i.e. the appearance of an object where there is no object to be grasped; ascertaining that this is like a dream, in order to abandon this mistake, all appearances of objects that are blue and yellow and so on are abandoned or destroyed (parihṛ-); then, the appearance of the world (viśvapratibhāsa) that is ascertained to be oneself (ātmaniścitta) is seen to be like the stainless sky on an autumn day at noon: appearanceless, unending sheer luminosity.[65]

This dissolution into emptiness is then followed by the visualization of the deity and re-emergence of the yogi as the deity. During the process of deity visualization, the deity is to be imaged as not solid or tangible, as "empty yet apparent", with the character of a mirage or a rainbow.[66] This visualization is to be combined with "divine pride", which is "the thought that one is oneself the deity being visualized."[67] Divine pride is different from common pride because it is based on compassion for others and on an understanding of emptiness.[68]

Some practices associated with the completion stage make use of an energetic system of human psycho-physiology composed of what is termed as energy channels (rtsa), winds or currents (rlung), and drops or charged particles (thig le). These subtle body energies as seen as "mounts" for consciousness, the physical component of awareness. They are said to converge at certain points along the spinal column called chakras.[69] Some practices which make use of this system include Trul khor and Tummo.

Other practices

Another form of Vajrayana practice are certain meditative techniques associated with Mahamudra and Dzogchen often termed "formless practices". These techniques do not rely on yidam visualization but on direct Pointing-out instruction from a master and are seen as the most advanced forms.[70]

In Tibetan Buddhism, advanced practices like deity yoga and the formless practices are usually preceded by or coupled with "preliminary practices" called ngondro which includes prostrations and recitations of the 100 syllable mantra.[71]

Another distinctive feature of Tantric Buddhism is its unique rituals, which are used as a substitute or alternative for the earlier abstract meditations.[72][73] They include death rituals (see phowa), tantric feasts (ganachakra) and Homa fire ritual, common in East Asian Tantric Buddhism.

Other unique practices in Tantric Buddhism include Dream yoga, the yoga of the intermediate state (at death) or Bardo and Chöd, in which the yogi ceremonially offers their body to be eaten by tantric deities.

Symbols and imagery

The Vajrayana uses a rich variety of symbols, terms and images which have multiple meanings according to a complex system of analogical thinking. In Vajrayana, symbols and terms are multi-valent, reflecting the microcosm and the macrocosm as in the phrase "As without, so within" (yatha bahyam tatha ’dhyatmam iti) from Abhayakaragupta’s Nispannayogavali.[74]

The Vajra

The Sanskrit term "vajra" denoted the thunderbolt, a legendary weapon and divine attribute that was made from an adamantine, or indestructible, substance and which could therefore pierce and penetrate any obstacle or obfuscation. It is the weapon of choice of Indra, the King of the Devas. As a secondary meaning, "vajra" symbolizes the ultimate nature of things which is described in the tantras as translucent, pure and radiant, but also indestructible and indivisible. It is also symbolic of the power of tantric methods to achieve its goals.[75]

A vajra is also a scepter-like ritual object (Standard Tibetan: རྡོ་རྗེ་ dorje), which has a sphere (and sometimes a gankyil) at its centre, and a variable number of spokes, 3, 5 or 9 at each end (depending on the sadhana), enfolding either end of the rod. The vajra is often traditionally employed in tantric rituals in combination with the bell or ghanta; symbolically, the vajra may represent method as well as great bliss and the bell stands for wisdom, specifically the wisdom realizing emptiness. The union of the two sets of spokes at the center of the wheel is said to symbolize the unity of wisdom (prajña) and compassion (karuna) as well as the sexual union of male and female deities.[76]

Imagery and ritual in deity yoga

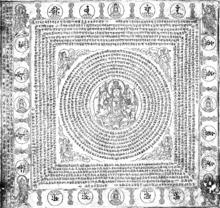

Representations of the deity, such as statues (murti), paintings (thangka), or mandala, are often employed as an aid to visualization, in Deity yoga. The use of visual aids, particularly microcosmic/macrocosmic diagrams, known as "mandalas", is another unique feature of Buddhist Tantra. Mandalas are symbolic depictions of the sacred space of the awakened Buddhas and Bodhisattvas as well as of the inner workings of the human person.[77] The macrocosmic symbolism of the mandala then, also represents the forces of the human body. The explanatory tantra of the Guhyasamaja tantra, the Vajramala, states: "The body becomes a palace, the hallowed basis of all the Buddhas."[78]

Mandalas are also sacred enclosures, sacred architecture that house and contain the uncontainable essence of a central deity or yidam and their retinue. In the book The World of Tibetan Buddhism, the Dalai Lama describes mandalas thus: "This is the celestial mansion, the pure residence of the deity." The Five Tathagatas or 'Five Buddhas', along with the figure of the Adi-Buddha, are central to many Vajrayana mandalas as they represent the "five wisdoms", which are the five primary aspects of primordial wisdom or Buddha-nature.[79]

All ritual in Vajrayana practice can be seen as aiding in this process of visualization and identification. The practitioner can use various hand implements such as a vajra, bell, hand-drum (damaru) or a ritual dagger (phurba), but also ritual hand gestures (mudras) can be made, special chanting techniques can be used, and in elaborate offering rituals or initiations, many more ritual implements and tools are used, each with an elaborate symbolic meaning to create a special environment for practice. Vajrayana has thus become a major inspiration in traditional Tibetan art.

Vajrayana textual tradition

The Vajrayana tradition has developed an extended body of texts:

Though we do not know precisely at present just how many Indian tantric Buddhist texts survive today in the language in which they were written, their number is certainly over one thousand five hundred; I suspect indeed over two thousand. A large part of this body of texts has also been translated into Tibetan, and a smaller part into Chinese. Aside from these, there are perhaps another two thousand or more works that are known today only from such translations. We can be certain as well that many others are lost to us forever, in whatever form. Of the texts that survive a very small proportion has been published; an almost insignificant percentage has been edited or translated reliably.[80]

Literary characteristics

Vajrayana texts exhibit a wide range of literary characteristics—usually a mix of verse and prose, almost always in a Sanskrit that "transgresses frequently against classical norms of grammar and usage," although also occasionally in various Middle Indic dialects or elegant classical Sanskrit.[81]

Dunhuang manuscripts

The Dunhuang manuscripts also contain Tibetan Tantric manuscripts. Dalton and Schaik (2007, revised) provide an excellent online catalogue listing 350 Tibetan Tantric Manuscripts] from Dunhuang in the Stein Collection of the British Library which is currently fully accessible online in discrete digitized manuscripts.[web 1] With the Wylie transcription of the manuscripts they are to be made discoverable online in the future.[82] These 350 texts are just a small portion of the vast cache of the Dunhuang manuscripts.

Schools of Vajrayana

Although there is historical evidence for Vajrayana Buddhism in Southeast Asia and elsewhere (see History of Vajrayana above), today the Vajrayana exists primarily in the form of the two major traditions of Tibetan Buddhism and Japanese Esoteric Buddhism in Japan known as Shingon (literally "True Speech", i.e. mantra), with a handful of minor subschools utilising lesser amounts of esoteric or tantric materials.

The distinction between traditions is not always rigid. For example, the tantra sections of the Tibetan Buddhist canon of texts sometimes include material not usually thought of as tantric outside the Tibetan Buddhist tradition, such as the Heart Sutra[83] and even versions of some material found in the Pali Canon.[84][lower-alpha 1]

Tibetan Buddhism

.jpg)

The Tibetan Buddhist schools, based on the lineages and textual traditions of the Kangyur and Tengyur of Tibet, are found in Tibet, Bhutan, northern India, Nepal, southwestern and northern China, Mongolia and various constituent republics of Russia that are adjacent to the area, such as Amur Oblast, Buryatia, Chita Oblast, the Tuva Republic and Khabarovsk Krai. Tibetan Buddhism is also the main religion in Kalmykia.

Vajrayana Buddhism was established in Tibet in the 8th century when Śāntarakṣita was brought to Tibet from India at the instigation of the Dharma King Trisong Detsen, some time before 767.

Nepalese Newar Buddhism

Newar Buddhism is practiced by Newars in Nepal. It is the only form of Vajrayana Buddhism in which the scriptures are written in Sanskrit. Its priests do not follow celibacy and are called vajracharya (literally "diamond-thunderbolt carriers").

Tantric Theravada

Tantric Theravada or "Esoteric Southern Buddhism" is a term for Vajrayana from Southeast Asia, where Theravada Buddhism is dominant. The monks of the Sri Lankan, Abhayagiri vihara once practiced forms of Vajrayana which were popular in the island.[85] Another tradition of this type was Ari Buddhism, which was common in Burma. The Tantric Buddhist 'Yogāvacara' tradition was a major Buddhist tradition in Cambodia, Laos and Thailand well into the modern era.[86] This form of Buddhism declined after the rise of Southeast Asian Buddhist modernism.

Bai Azhaliism

Azhaliism (Chinese: 阿吒力教 Āzhālìjiào) is an Esoteric Buddhist religion practiced among the Bai people of China.[87][88]

Chinese Esoteric Buddhism

Esoteric teachings followed the same route into northern China as Buddhism itself, arriving via the Silk Road sometime during the first half of the 7th century, during the Tang dynasty, just as Buddhism was reaching its zenith in China, and received sanction from the emperors of the Tang dynasty. During this time, three great masters came from India to China: Śubhakarasiṃha, Vajrabodhi, and Amoghavajra. These three masters brought the esoteric teachings to their height of popularity in China.[89] During this era, the two main source texts were the Mahāvairocana Abhisaṃbodhi Tantra, and the Tattvasaṃgraha Tantra. Traditions in the Sinosphere still exist for these teachings, and they more or less share the same doctrines as Shingon, with many of its students themselves traveling to Japan to be given transmission at Mount Koya.

Esoteric methods were naturally incorporated into Chinese Buddhism during the Tang dynasty. Śubhakarasiṃha's most eminent disciple, Master Yixing (Ch. 一行), was a member of the Chán school. In such a way, in Chinese Buddhism there was no major distinction between exoteric and esoteric practices, and the northern school of Chán Buddhism even became known for its esoteric practices of dhāraṇīs and mantras.[90][91]

The practice of Tantric Buddhism in Western Xia led to the spread of some sexually related customs. Before they could get married to men of their own ethnicity when they reached 30 years old, Uighur women in Shanxi in the 12th century had children after having sex with multiple Han Chinese men, with her desirability as a wife corresponding to if she had been with a large number of men.[92][93][94]

During the Yuan dynasty, the Mongol emperors made Esoteric Buddhism the official religion of China, and Tibetan lamas were given patronage at the court.[95] A common perception was that this patronage of lamas caused corrupt forms of tantra to become widespread.[95] When the Mongol Yuan dynasty was overthrown and the Ming dynasty was established, the Tibetan lamas were expelled from the court, and this form of Buddhism was denounced as not being an orthodox path.[95]

In late imperial China, the early traditions of Esoteric Buddhism were still thriving in Buddhist communities. Robert Gimello has also observed that in these communities, the esoteric practices associated with Cundī were extremely popular among both the populace and the elite.[96]

In China and countries with large Chinese populations such as Taiwan, Malaysia, and Singapore, Esoteric Buddhism is most commonly referred to with the Chinese term Mìzōng (密宗), literally "Esoteric Tradition" or "Mystery Tradition". Traditions of specifically Chinese Esoteric Buddhism are most commonly referred to as Tángmì (唐密), "Tang Esotericism" or "Tang Mysteries", or Hànchuán Mìzōng (漢傳密宗), "Han Transmission of the Esoteric Tradition" (Hànmì 漢密, "Han Mysteries", for short), or even Dōngmì (東密), "Eastern Esotericism" or "Eastern Mysteries", separating itself from Tibetan and Newar traditions. These schools more or less share the same doctrines as Shingon. There is an ongoing revival of Tangmi or Hanmi in contemporary China.[97] [98]

Japan

Shingon Buddhism

The Shingon school is found in Japan and includes practices, known in Japan as Mikkyō ("Esoteric (or Mystery) Teaching"), which are similar in concept to those in Vajrayana Buddhism. The lineage for Shingon Buddhism differs from that of Tibetan Vajrayana, having emerged from India during the 9th-11th centuries in the Pala Dynasty and Central Asia (via China) and is based on earlier versions of the Indian texts than the Tibetan lineage. Shingon shares material with Tibetan Buddhism–-such as the esoteric sutras (called Tantras in Tibetan Buddhism) and mandalas – but the actual practices are not related. The primary texts of Shingon Buddhism are the Mahavairocana Sutra and Vajrasekhara Sutra. The founder of Shingon Buddhism was Kukai, a Japanese monk who studied in China in the 9th century during the Tang dynasty and brought back Vajrayana scriptures, techniques and mandalas then popular in China. The school mostly died out or was merged into other schools in China towards the end of the Tang dynasty but flourished in Japan. Shingon is one of the few remaining branches of Buddhism in the world that continues to use the siddham script of the Sanskrit language.

Tendai Buddhism

Although the Tendai school in China and Japan does employ some esoteric practices, these rituals came to be considered of equal importance with the exoteric teachings of the Lotus Sutra. By chanting mantras, maintaining mudras, or practicing certain forms of meditation, Tendai maintains that one is able to understand sense experiences as taught by the Buddha, have faith that one is innately an enlightened being, and that one can attain enlightenment within the current lifetime.

Shugendō

Shugendō was founded in 7th century Japan by the ascetic En no Gyōja, based on the Queen's Peacocks Sutra. With its origins in the solitary hijiri back in the 7th century, Shugendō evolved as a sort of amalgamation between Esoteric Buddhism, Shinto and several other religious influences including Taoism. Buddhism and Shinto were amalgamated in the shinbutsu shūgō, and Kūkai's syncretic religion held wide sway up until the end of the Edo period, coexisting with Shinto elements within Shugendō[99]

In 1613 during the Edo period, the Tokugawa Shogunate issued a regulation obliging Shugendō temples to belong to either Shingon or Tendai temples. During the Meiji Restoration, when Shinto was declared an independent state religion separate from Buddhism, Shugendō was banned as a superstition not fit for a new, enlightened Japan. Some Shugendō temples converted themselves into various officially approved Shintō denominations. In modern times, Shugendō is practiced mainly by Tendai and Shingon sects, retaining an influence on modern Japanese religion and culture.[100]

Academic study difficulties

Serious Vajrayana academic study in the Western world is in early stages due to the following obstacles:[101]

- Although a large number of Tantric scriptures are extant, they have not been formally ordered or systematized.

- Due to the esoteric initiatory nature of the tradition, many practitioners will not divulge information or sources of their information.

- As with many different subjects, it must be studied in context and with a long history spanning many different cultures.

- Ritual as well as doctrine need to be investigated.

Buddhist tantric practice are categorized as secret practice; this is to avoid misinformed people from harmfully misusing the practices. A method to keep this secrecy is that tantric initiation is required from a master before any instructions can be received about the actual practice. During the initiation procedure in the highest class of tantra (such as the Kalachakra), students must take the tantric vows which commit them to such secrecy.[web 2] "Explaining general tantra theory in a scholarly manner, not sufficient for practice, is likewise not a root downfall. Nevertheless, it weakens the effectiveness of our tantric practice." [web 3]

Terminology

The terminology associated with Vajrayana Buddhism can be confusing. Most of the terms originated in the Sanskrit language of tantric Indian Buddhism and may have passed through other cultures, notably those of Japan and Tibet, before translation for the modern reader. Further complications arise as seemingly equivalent terms can have subtle variations in use and meaning according to context, the time and place of use. A third problem is that the Vajrayana texts employ the tantric tradition of twilight language, a means of instruction that is deliberately coded. These obscure teaching methods relying on symbolism as well as synonym, metaphor and word association add to the difficulties faced by those attempting to understand Vajrayana Buddhism:

In the Vajrayana tradition, now preserved mainly in Tibetan lineages, it has long been recognized that certain important teachings are expressed in a form of secret symbolic language known as saṃdhyā-bhāṣā, 'Twilight Language'. Mudrās and mantras, maṇḍalas and cakras, those mysterious devices and diagrams that were so much in vogue in the pseudo-Buddhist hippie culture of the 1960s, were all examples of Twilight Language [...] [102]

The term Tantric Buddhism was not one originally used by those who practiced it. As scholar Isabelle Onians explains:

"Tantric Buddhism" [...] is not the transcription of a native term, but a rather modern coinage, if not totally occidental. For the equivalent Sanskrit tāntrika is found, but not in Buddhist texts. Tāntrika is a term denoting someone who follows the teachings of scriptures known as Tantras, but only in Saivism, not Buddhism [...] Tantric Buddhism is a name for a phenomenon which calls itself, in Sanskrit, Mantranaya, Vajrayāna, Mantrayāna or Mantramahāyāna (and apparently never Tantrayāna). Its practitioners are known as mantrins, yogis, or sādhakas. Thus, our use of the anglicised adjective “Tantric” for the Buddhist religion taught in Tantras is not native to the tradition, but is a borrowed term which serves its purpose.[103]

See also

- Buddhism

- Buddhism in Bhutan

- Buddhism in the Maldives

- Buddhism in Nepal

- Buddhism in Russia

- Drukpa Lineage

- Gyuto Order

- Tawang Taktshang Monastery

- Kashmir Shaivism

- Category:Tibetan Buddhist teachers

- Western equivalent

Notes

References

- ↑ Macmillan Publishing 2004, p. 875-876.

- ↑ Ray, Reginald A.; Indestructible Truth: The Living Spirituality of Tibetan Buddhism, 2000

- ↑ Reynolds, John Myrdhin. "The Mahasiddha Tradition in Tibet". Vajranatha. Vajranatha. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- ↑ Snellgrove, David. (1987) Indo-Tibetan Buddhism: Indian Buddhists and their Tibetan successors. pp 168.

- ↑ Schumann 1974, p. 163.

- 1 2 3 Kitagawa 2002, p. 80.

- ↑ Dowman, The Eighty-four Mahasiddhas and the Path of Tantra - Introduction to Masters of Mahamudra, 1984. http://keithdowman.net/essays/introduction-mahasiddhas-and-tantra.html

- ↑ Snellgrove, David. (1987) Indo-Tibetan Buddhism: Indian Buddhists and their Tibetan successors. pp 122.

- ↑ Williams, Wynne, Tribe; Buddhist Thought: A Complete Introduction to the Indian Tradition, page 225.

- ↑ Osto, Douglas. “Proto–Tantric” Elements in The Gandavyuha sutra. Journal of Religious History Vol. 33, No. 2, June 2009.

- ↑ Snellgrove, David. (1987) Indo-Tibetan Buddhism: Indian Buddhists and their Tibetan successors. pp 147.

- ↑ Williams, Wynne, Tribe; Buddhist Thought: A Complete Introduction to the Indian Tradition, page 205-206.

- ↑ Williams, Wynne, Tribe; Buddhist Thought: A Complete Introduction to the Indian Tradition, page 210.

- ↑ Wayman, Alex; The Buddhist Tantras: Light on Indo-Tibetan Esotericism, Routledge, (2008), page 19.

- ↑ Williams, Wynne, Tribe; Buddhist Thought: A Complete Introduction to the Indian Tradition, page 212.

- ↑ Tajima, R. Étude sur le Mahàvairocana-Sùtra

- ↑ Williams, Wynne, Tribe; Buddhist Thought: A Complete Introduction to the Indian Tradition, page 205-206.

- ↑ Schumann 1974.

- ↑ Gordon White, David; Review of "Indian Esoteric Buddhism", by Ronald M. Davidson, University of California, Santa Barbara JIATS, no. 1 (October 2005), THL #T1223, 11 pp.

- ↑ Sanderson, Alexis. "The Śaiva Age: The Rise and Dominance of Śaivism during the Early Medieval Period." In: Genesis and Development of Tantrism, edited by Shingo Einoo. Tokyo: Institute of Oriental Culture, University of Tokyo, 2009. Institute of Oriental Culture Special Series, 23, pp. 124.

- ↑ Sanderson, Alexis. "The Śaiva Age: The Rise and Dominance of Śaivism during the Early Medieval Period." In: Genesis and Development of Tantrism, edited by Shingo Einoo. Tokyo: Institute of Oriental Culture, University of Tokyo, 2009. Institute of Oriental Culture Special Series, 23, pp. 129-131.

- ↑ Sanderson, Alexis; Vajrayana:, Origin and Function, 1994

- ↑ Sanderson, Alexis. "The Śaiva Age: The Rise and Dominance of Śaivism during the Early Medieval Period." In: Genesis and Development of Tantrism, edited by Shingo Einoo. Tokyo: Institute of Oriental Culture, University of Tokyo, 2009. Institute of Oriental Culture Special Series, 23, pp. 144-145.

- ↑ Huber, Toni (2008). The holy land reborn : pilgrimage & the Tibetan reinvention of Buddhist India. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 94–95. ISBN 978-0-226-35648-8.

- ↑ Wayman, Alex; The Buddhist Tantras: Light on Indo-Tibetan Esotericism, 2013, page 3.

- ↑ L. de la Vallée Poussin, Bouddhisme, études et matériaux, pp. 174-5.

- ↑ Beyer, Stephan; The Cult of Tārā: Magic and Ritual in Tibet, 1978, page 69

- ↑ Snellgrove, David. (1987) Indo-Tibetan Buddhism: Indian Buddhists and their Tibetan successors. pp 125.

- ↑ Wayman, Alex; Yoga of the Guhyasamajatantra: The arcane lore of forty verses : a Buddhist Tantra commentary, 1977, page 56.

- ↑ Williams, Wynne, Tribe; Buddhist Thought: A Complete Introduction to the Indian Tradition, page 202.

- ↑ Snellgrove, David. (1987) Indo-Tibetan Buddhism: Indian Buddhists and their Tibetan successors. pp 125-126.

- ↑ Williams, Wynne, Tribe; Buddhist Thought: A Complete Introduction to the Indian Tradition, page 202.

- ↑ Snellgrove, David. (1987) Indo-Tibetan Buddhism: Indian Buddhists and their Tibetan successors. pp 126.

- ↑ Duckworth, Douglas; Tibetan Mahāyāna and Vajrayāna in "A companion to Buddhist philosophy", page 100.

- ↑ Koppl, Heidi. Establishing Appearances as Divine. Snow Lion Publications 2008, chapter 4.

- ↑ Wayman, Alex; The Buddhist Tantras: Light on Indo-Tibetan Esotericism, 2013, page 5.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Macmillan Publishing 2004, p. 875.

- ↑ Palmo, Tenzin (2002). Reflections on a Mountain Lake:Teachings on Practical Buddhism. Snow Lion Publications. pp. 224–5. ISBN 1-55939-175-8.

- ↑ Williams, Wynne, Tribe; Buddhist Thought: A Complete Introduction to the Indian Tradition, pages 198, 231.

- ↑ Dhammasaavaka. The Buddhism Primer: An Introduction to Buddhism, p. 79. ISBN 1-4116-6334-9

- ↑ Ray 2001.

- ↑ Williams, Wynne, Tribe; Buddhist Thought: A Complete Introduction to the Indian Tradition, page 198.

- ↑ Morreale, Don (1998) The Complete Guide to Buddhist America ISBN 1-57062-270-1 p.215

- ↑ Trungpa, Chögyam and Chödzin, Sherab (1992) The Lion's Roar: An Introduction to Tantra ISBN 0-87773-654-5 p. 144.

- ↑ Williams, Wynne, Tribe; Buddhist Thought: A Complete Introduction to the Indian Tradition, page 236.

- ↑ Williams, Wynne, Tribe; Buddhist Thought: A Complete Introduction to the Indian Tradition, page 236.

- ↑ Williams, Wynne, Tribe; Buddhist Thought: A Complete Introduction to the Indian Tradition, page 236.

- ↑ Williams, Wynne, Tribe; Buddhist Thought: A Complete Introduction to the Indian Tradition, page 237.

- ↑ Wayman, Alex; The Buddhist Tantras: Light on Indo-Tibetan esotericism, page 39.

- ↑ Simmer-Brown, Judith; Dakini's Warm Breath: The Feminine Principle in Tibetan Buddhism, 2002, page 217

- ↑ Simmer-Brown, Judith; Dakini's Warm Breath: The Feminine Principle in Tibetan Buddhism, 2002, page 217-219

- ↑ Simmer-Brown, Judith; Dakini's Warm Breath: The Feminine Principle in Tibetan Buddhism, 2002, page 219

- ↑ Williams, Wynne, Tribe; Buddhist Thought: A Complete Introduction to the Indian Tradition, pages 198, 240.

- ↑ Williams, Wynne, Tribe; Buddhist Thought: A Complete Introduction to the Indian Tradition, pages 198, 240.

- ↑ Williams, Wynne, Tribe; Buddhist Thought: A Complete Introduction to the Indian Tradition, pages 198, 242.

- ↑ Tsongkhapa, Tantric Ethics: An Explanation of the Precepts for Buddhist Vajrayana Practice ISBN 0-86171-290-0, page 46.

- ↑ Hopkins, Jeffrey; Tantric Techniques, 2008, pp 220, 251

- ↑ Williams, Wynne, Tribe; Buddhist Thought: A Complete Introduction to the Indian Tradition, page 223-224.

- ↑ Wayman, Alex; Yoga of the Guhyasamajatantra: The arcane lore of forty verses : a Buddhist Tantra commentary, 1977, page 63.

- ↑ Wayman, Alex; The Buddhist Tantras: Light on Indo-Tibetan esotericism, page 36.

- ↑ Garson, Nathaniel DeWitt; Penetrating the Secret Essence Tantra: Context and Philosophy in the Mahayoga System of rNying-ma Tantra, 2004, p. 37

- ↑ Power, John; Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism, page 271

- ↑ Garson, Nathaniel DeWitt; Penetrating the Secret Essence Tantra: Context and Philosophy in the Mahayoga System of rNying-ma Tantra, 2004, p. 52

- ↑ Garson, Nathaniel DeWitt; Penetrating the Secret Essence Tantra: Context and Philosophy in the Mahayoga System of rNying-ma Tantra, 2004, p. 53

- ↑ Tomlinson, Davey K; The tantric context of Ratnākaraśānti’s theory of consciousness

- ↑ Ray, Reginald A. Secret of the Vajra World, The Tantric Buddhism of Tibet, Shambala, page 218.

- ↑ Cozort, Daniel; Highest Yoga Tantra, page 57.

- ↑ Power, John; Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism, page 273.

- ↑ Garson, Nathaniel DeWitt; Penetrating the Secret Essence Tantra: Context and Philosophy in the Mahayoga System of rNying-ma Tantra, 2004, p. 45

- ↑ Ray, Reginald A. Secret of the Vajra World, The Tantric Buddhism of Tibet, Shambala, page 112-113.

- ↑ Ray, Reginald A. Secret of the Vajra World, The Tantric Buddhism of Tibet, Shambala, page 178.

- ↑ Warder 1999, p. 466.

- ↑ Hawkins 1999, p. 24.

- ↑ Wayman, Alex; Yoga of the Guhyasamajatantra: The arcane lore of forty verses : a Buddhist Tantra commentary, 1977, page 62.

- ↑ Williams, Wynne, Tribe; Buddhist Thought: A Complete Introduction to the Indian Tradition, page 217.

- ↑ Williams, Wynne, Tribe; Buddhist Thought: A Complete Introduction to the Indian Tradition, page 219.

- ↑ Garson, Nathaniel DeWitt; Penetrating the Secret Essence Tantra: Context and Philosophy in the Mahayoga System of rNying-ma Tantra, 2004, p. 42

- ↑ Wayman, Alex; The Buddhist Tantras: Light on Indo-Tibetan esotericism, page 83.

- ↑ Ray, Reginald A. Secret of the Vajra World, The Tantric Buddhism of Tibet, Shambala, page 130.

- ↑ Isaacson, Harunaga (1998). Tantric Buddhism in India (from c. 800 to c. 1200). In: Buddhismus in Geschichte und Gegenwart. Band II. Hamburg. pp.23–49. (Internal publication of Hamburg University.) pg 3 PDF

- ↑ Isaacson

- ↑ Dalton, Jacob & van Schaik, Sam (2007). Catalogue of the Tibetan Tantric Manuscripts from Dunhuang in the Stein Collection [Online]. Second electronic edition. International Dunhuang Project. Source: (accessed: Tuesday February 2, 2010)

- ↑ Conze, The Prajnaparamita Literature

- ↑ Peter Skilling, Mahasutras, volume I, 1994, Pali Text Society, Lancaster, page xxiv

- ↑ Cousins, L.S. (1997), "Aspects of Southern Esoteric Buddhism", in Peter Connolly and Sue Hamilton (eds.), Indian Insights: Buddhism, Brahmanism and Bhakd Papers from the Annual Spalding Symposium on Indian Religions, Luzac Oriental, London: 185-207, 410. ISBN 1-898942-153

- ↑ Kate Crosby, Traditional Theravada Meditation and its Modern-Era Suppression Hong Kong: Buddha Dharma Centre of Hong Kong, 2013, ISBN 978-9881682024

- ↑ Huang, Zhengliang; Zhang, Xilu (2013). "Research Review of Bai Esoteric Buddhist Azhali Religion Since the 20th Century". Journal of Dali University.

- ↑ Wu, Jiang (2011). Enlightenment in Dispute: The Reinvention of Chan Buddhism in Seventeenth-Century China. USA: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0199895562. p. 441

- ↑ Baruah, Bibbhuti (2008) Buddhist Sects and Sectarianism: p. 170

- ↑ Sharf, Robert (2001) Coming to Terms With Chinese Buddhism: A Reading of the Treasure Store Treatise: p. 268

- ↑ Faure, Bernard (1997) The Will to Orthodoxy: A Critical Genealogy of Northern Chan Buddhism: p. 85

- ↑ Michal Biran (15 September 2005). The Empire of the Qara Khitai in Eurasian History: Between China and the Islamic World. Cambridge University Press. pp. 164–. ISBN 978-0-521-84226-6.

- ↑ Dunnell, Ruth W. (1983). Tanguts and the Tangut State of Ta Hsia. Princeton University., page 228

- ↑ 洪, 皓. 松漠紀聞.

- 1 2 3 Nan Huaijin. Basic Buddhism: Exploring Buddhism and Zen. York Beach: Samuel Weiser. 1997. p. 99.

- ↑ Jiang, Wu (2008). Enlightenment in Dispute: The Reinvention of Chan Buddhism in Seventeenth-Century China: p. 146

- ↑ Tangmi movement website

- ↑ Chinese Esoteric Buddhist School

- ↑ Miyake, Hitoshi. Shugendo in History. pp45–52.

- ↑ 密教と修験道 Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Akira 1993, p. 9.

- ↑ Bucknell, Roderick & Stuart-Fox, Martin (1986). The Twilight Language: Explorations in Buddhist Meditation and Symbolism. Curzon Press: London. ISBN 0-312-82540-4.

- ↑ Isabelle Onians, "Tantric Buddhist Apologetics, or Antinomianism as a Norm," D.Phil. dissertation, Oxford, Trinity Term 2001 pg 8

Web references

Sources

- Akira, Hirakawa (1993), Paul Groner, ed., History of Indian Buddhism, Translated by Paul Groner, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers

- Banerjee, S. C. (1977), Tantra in Bengal: A Study in Its Origin, Development and Influence, Manohar, ISBN 81-85425-63-9

- Buswell, Robert E., ed. (2004), Encyclopedia of Buddhism, Macmillan Reference USA, ISBN 0-02-865910-4

- Datta, Amaresh (2006), The Encyclopaedia Of Indian Literature (Volume One (A To Devo), Volume 1, Sahitya Akademi publications, ISBN 978-81-260-1803-1

- Harding, Sarah (1996), Creation and Completion - Essential Points of Tantric Meditation, Boston: Wisdom Publications

- Hawkins, Bradley K. (1999), Buddhism, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-21162-X

- Hua, Hsuan; Heng Chih; Heng Hsien; David Rounds; Ron Epstein; et al. (2003), The Shurangama Sutra - Sutra Text and Supplements with Commentary by the Venerable Master Hsuan Hua, Burlingame, California: Buddhist Text Translation Society, ISBN 0-88139-949-3, archived from the original on May 29, 2009

- Kitagawa, Joseph Mitsuo (2002), The Religious Traditions of Asia: Religion, History, and Culture, Routledge, ISBN 0-7007-1762-5

- Mishra, Baba; Dandasena, P.K. (2011), Settlement and urbanization in ancient Orissa

- Patrul Rinpoche (1994), Brown, Kerry; Sharma, Sima, eds., The Words of My Perfect Teacher (Tibetan title: kunzang lama'i shelung). Translated by the Padmakara Translation Group. With a foreword by the Dalai Lama, San Francisco, California, USA: HarperCollinsPublishers, ISBN 0-06-066449-5

- Ray, Reginald A (2001), Secret of the Vajra World: The Tantric Buddhism of Tibet, Boston: Shambhala Publications

- Schumann, Hans Wolfgang (1974), Buddhism: an outline of its teachings and schools, Theosophical Pub. House

- Snelling, John (1987), The Buddhist handbook. A Complete Guide to Buddhist Teaching and Practice, London: Century Paperbacks

- Wardner, A.K. (1999), Indian Buddhism, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers

- Williams, Paul; Tribe, Anthony (2000), Buddhist Thought: A complete introduction to the Indian tradition, Routledge, ISBN 0-203-18593-5

Further reading

- Rongzom Chözang; Köppl, Heidi I. (trans) (2008). Establishing Appearances as Divine. Snow Lion. pp. 95–108. ISBN 9781559392884.

- Kongtrul, Jamgon; Thrangu Rinpoche; Harding, Sarah (2002). Creation and Completion: Essential Points of Tantric Meditation. Wisdom Publications. ISBN 0-86171-312-5.

- Kongtrul, Jamgon; Barron, Richard (1998). Buddhist Ethics. The Treasury of Knowledge (book 5). Ithaca: Snow Lion. pp. 215–306. ISBN 1-55939-191-X.

- Kongtrul, Jamgon; Guarisco, Elio; McLeod, Ingrid (2004). Systems of Buddhist Tantra:The Indestructible Way of Secret Mantra. The Treasury of Knowledge (book 6 part 4). Ithaca: Snow Lion. ISBN 9781559392105.

- Kongtrul, Jamgon; Guarisco, Elio; McLeod, Ingrid (2008). The Elements of Tantric Practice:A General Exposition of the Process of Meditation in the Indestructible Way of Secret Mantra. The Treasury of Knowledge (book 8 part 3). Ithaca: Snow Lion. ISBN 9781559393058.

- Kongtrul, Jamgon; Harding, Sarah (2007). Esoteric Instructions: A Detailed Presentation of the Process of Meditation in Vajrayana. The Treasury of Knowledge (book 8 part 4). Ithaca, NY: Snow Lion Publications. ISBN 1-55939-284-3.

- Kongtrul, Jamgon; Barron, Richard (2010). Journey and Goal: An Analysis of the Spiritual Paths and Levels to be Traversed and the Consummate Fruition state. The Treasury of Knowledge (books 9 & 10). Ithaca, NY: Snow Lion Publications. pp. 159–251, 333–451. ISBN 1-55939-360-2.

- Tantric Ethics: An Explanation of the Precepts for Buddhist Vajrayana Practice by Tson-Kha-Pa, ISBN 0-86171-290-0

- Perfect Conduct: Ascertaining the Three Vows by Ngari Panchen, Dudjom Rinpoche, ISBN 0-86171-083-5

- Āryadeva's Lamp that Integrates the Practices (Caryāmelāpakapradīpa): The Gradual Path of Vajrayāna Buddhism according to the Esoteric Community Noble Tradition, ed. and trans by Christian K. Wedemeyer (New York: AIBS/Columbia Univ. Press, 2007). ISBN 978-0-9753734-5-3

- S. C. Banerji, Tantra in Bengal: A Study of Its Origin, Development and Influence, Manohar (1977) (2nd ed. 1992). ISBN 8185425639

- Arnold, Edward A. on behalf of Namgyal Monastery Institute of Buddhist Studies, fore. by Robert A. F. Thurman. As Long As Space Endures: Essays on the Kalacakra Tantra in Honor of H.H. the Dalai Lama, Snow Lion Publications, 2009.

- Snellgrove, David L.: Indo-Tibetan Buddhism. Indian Buddhists and Their Tibetan Successors. London: Serindia, 1987.

External links

| Wikiversity has learning resources about Vajrayāna |