Virtual private network

A virtual private network (VPN) extends a private network across a public network, and enables users to send and receive data across shared or public networks as if their computing devices were directly connected to the private network. ("In the simplest terms, it creates a secure, encrypted connection, which can be thought of as a tunnel, between your computer and a server operated by the VPN service."[1]) Applications running across the VPN may therefore benefit from the functionality, security, and management of the private network.[2]

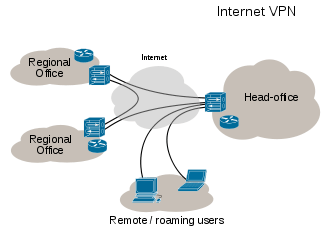

VPNs may allow employees to securely access a corporate intranet while located outside the office. They are used to securely connect geographically separated offices of an organization, creating one cohesive network. Individual Internet users may secure their wireless transactions with a VPN, to circumvent geo-restrictions and censorship, or to connect to proxy servers for the purpose of protecting personal identity and location. However, some Internet sites block access to known VPN technology to prevent the circumvention of their geo-restrictions.

A VPN is created by establishing a virtual point-to-point connection through the use of dedicated connections, virtual tunneling protocols, or traffic encryption. A VPN available from the public Internet can provide some of the benefits of a wide area network (WAN). From a user perspective, the resources available within the private network can be accessed remotely.[3]

Traditional VPNs are characterized by a point-to-point topology, and they do not tend to support or connect broadcast domains, so services such as Microsoft Windows NetBIOS may not be fully supported or work as they would on a local area network (LAN). Designers have developed VPN variants, such as Virtual Private LAN Service (VPLS), and layer-2 tunneling protocols, to overcome this limitation.

Some VPNs have been banned in China and Russia.[4]

Types

Early data networks allowed VPN-style remote connectivity through dial-up modem or through leased line connections utilizing Frame Relay and Asynchronous Transfer Mode (ATM) virtual circuits, provisioned through a network owned and operated by telecommunication carriers. These networks are not considered true VPNs because they passively secure the data being transmitted by the creation of logical data streams.[5] They have been replaced by VPNs based on IP and IP/Multi-protocol Label Switching (MPLS) Networks, due to significant cost-reductions and increased bandwidth[6] provided by new technologies such as Digital Subscriber Line (DSL)[7] and fiber-optic networks.

VPNs can be either remote-access (connecting a computer to a network) or site-to-site (connecting two networks). In a corporate setting, remote-access VPNs allow employees to access their company's intranet from home or while travelling outside the office, and site-to-site VPNs allow employees in geographically disparate offices to share one cohesive virtual network. A VPN can also be used to interconnect two similar networks over a dissimilar middle network; for example, two IPv6 networks over an IPv4 network.[8]

VPN systems may be classified by:

- The protocols used to tunnel the traffic

- The tunnel's termination point location, e.g., on the customer edge or network-provider edge

- The type of topology of connections, such as site-to-site or network-to-network

- The levels of security provided

- The OSI layer they present to the connecting network, such as Layer 2 circuits or Layer 3 network connectivity

- The number of simultaneous connections

Security mechanisms

VPNs cannot make online connections completely anonymous, but they can usually increase privacy and security. To prevent disclosure of private information, VPNs typically allow only authenticated remote access using tunneling protocols and encryption techniques.

The VPN security model provides:

- Confidentiality such that even if the network traffic is sniffed at the packet level (see network sniffer and Deep packet inspection), an attacker would only see encrypted data

- Sender authentication to prevent unauthorized users from accessing the VPN

- Message integrity to detect any instances of tampering with transmitted messages

Secure VPN protocols include the following:

- Internet Protocol Security (IPsec) was initially developed by the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) for IPv6, which was required in all standards-compliant implementations of IPv6 before RFC 6434 made it only a recommendation.[9] This standards-based security protocol is also widely used with IPv4 and the Layer 2 Tunneling Protocol. Its design meets most security goals: authentication, integrity, and confidentiality. IPsec uses encryption, encapsulating an IP packet inside an IPsec packet. De-encapsulation happens at the end of the tunnel, where the original IP packet is decrypted and forwarded to its intended destination.

- Transport Layer Security (SSL/TLS) can tunnel an entire network's traffic (as it does in the OpenVPN project and SoftEther VPN project[10]) or secure an individual connection. A number of vendors provide remote-access VPN capabilities through SSL. An SSL VPN can connect from locations where IPsec runs into trouble with Network Address Translation and firewall rules.

- Datagram Transport Layer Security (DTLS) – used in Cisco AnyConnect VPN and in OpenConnect VPN[11] to solve the issues SSL/TLS has with tunneling over UDP.

- Microsoft Point-to-Point Encryption (MPPE) works with the Point-to-Point Tunneling Protocol and in several compatible implementations on other platforms.

- Microsoft Secure Socket Tunneling Protocol (SSTP) tunnels Point-to-Point Protocol (PPP) or Layer 2 Tunneling Protocol traffic through an SSL 3.0 channel. (SSTP was introduced in Windows Server 2008 and in Windows Vista Service Pack 1.)

- Multi Path Virtual Private Network (MPVPN). Ragula Systems Development Company owns the registered trademark "MPVPN".[12]

- Secure Shell (SSH) VPN – OpenSSH offers VPN tunneling (distinct from port forwarding) to secure remote connections to a network or to inter-network links. OpenSSH server provides a limited number of concurrent tunnels. The VPN feature itself does not support personal authentication.[13][14][15]

Authentication

Tunnel endpoints must be authenticated before secure VPN tunnels can be established. User-created remote-access VPNs may use passwords, biometrics, two-factor authentication or other cryptographic methods. Network-to-network tunnels often use passwords or digital certificates. They permanently store the key to allow the tunnel to establish automatically, without intervention from the administrator.

Routing

Tunneling protocols can operate in a point-to-point network topology that would theoretically not be considered as a VPN, because a VPN by definition is expected to support arbitrary and changing sets of network nodes. But since most router implementations support a software-defined tunnel interface, customer-provisioned VPNs often are simply defined tunnels running conventional routing protocols.

Provider-provisioned VPN building-blocks

Depending on whether a provider-provisioned VPN (PPVPN) operates in layer 2 or layer 3, the building blocks described below may be L2 only, L3 only, or combine them both. Multi-protocol label switching (MPLS) functionality blurs the L2-L3 identity.

RFC 4026 generalized the following terms to cover L2 and L3 VPNs, but they were introduced in RFC 2547.[16] More information on the devices below can also be found in Lewis, Cisco Press.[17]

- Customer (C) devices

A device that is within a customer's network and not directly connected to the service provider's network. C devices are not aware of the VPN.

- Customer Edge device (CE)

A device at the edge of the customer's network which provides access to the PPVPN. Sometimes it's just a demarcation point between provider and customer responsibility. Other providers allow customers to configure it.

- Provider edge device (PE)

A PE is a device, or set of devices, at the edge of the provider network which connects to customer networks through CE devices and presents the provider's view of the customer site. PEs are aware of the VPNs that connect through them, and maintain VPN state.

- Provider device (P)

A P device operates inside the provider's core network and does not directly interface to any customer endpoint. It might, for example, provide routing for many provider-operated tunnels that belong to different customers' PPVPNs. While the P device is a key part of implementing PPVPNs, it is not itself VPN-aware and does not maintain VPN state. Its principal role is allowing the service provider to scale its PPVPN offerings, for example, by acting as an aggregation point for multiple PEs. P-to-P connections, in such a role, often are high-capacity optical links between major locations of providers.

User-visible PPVPN services

OSI Layer 2 services

- Virtual LAN

A Layer 2 technique that allow for the coexistence of multiple LAN broadcast domains, interconnected via trunks using the IEEE 802.1Q trunking protocol. Other trunking protocols have been used but have become obsolete, including Inter-Switch Link (ISL), IEEE 802.10 (originally a security protocol but a subset was introduced for trunking), and ATM LAN Emulation (LANE).

- Virtual private LAN service (VPLS)

Developed by Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, VLANs allow multiple tagged LANs to share common trunking. VLANs frequently comprise only customer-owned facilities. Whereas VPLS as described in the above section (OSI Layer 1 services) supports emulation of both point-to-point and point-to-multipoint topologies, the method discussed here extends Layer 2 technologies such as 802.1d and 802.1q LAN trunking to run over transports such as Metro Ethernet.

As used in this context, a VPLS is a Layer 2 PPVPN, rather than a private line, emulating the full functionality of a traditional local area network (LAN). From a user standpoint, a VPLS makes it possible to interconnect several LAN segments over a packet-switched, or optical, provider core; a core transparent to the user, making the remote LAN segments behave as one single LAN.[18]

In a VPLS, the provider network emulates a learning bridge, which optionally may include VLAN service.

- Pseudo wire (PW)

PW is similar to VPLS, but it can provide different L2 protocols at both ends. Typically, its interface is a WAN protocol such as Asynchronous Transfer Mode or Frame Relay. In contrast, when aiming to provide the appearance of a LAN contiguous between two or more locations, the Virtual Private LAN service or IPLS would be appropriate.

- Ethernet over IP tunneling

EtherIP (RFC 3378) is an Ethernet over IP tunneling protocol specification. EtherIP has only packet encapsulation mechanism. It has no confidentiality nor message integrity protection. EtherIP was introduced in the FreeBSD network stack[19] and the SoftEther VPN[20] server program.

- IP-only LAN-like service (IPLS)

A subset of VPLS, the CE devices must have Layer 3 capabilities; the IPLS presents packets rather than frames. It may support IPv4 or IPv6.

OSI Layer 3 PPVPN architectures

This section discusses the main architectures for PPVPNs, one where the PE disambiguates duplicate addresses in a single routing instance, and the other, virtual router, in which the PE contains a virtual router instance per VPN. The former approach, and its variants, have gained the most attention.

One of the challenges of PPVPNs involves different customers using the same address space, especially the IPv4 private address space.[21] The provider must be able to disambiguate overlapping addresses in the multiple customers' PPVPNs.

- BGP/MPLS PPVPN

In the method defined by RFC 2547, BGP extensions advertise routes in the IPv4 VPN address family, which are of the form of 12-byte strings, beginning with an 8-byte Route Distinguisher (RD) and ending with a 4-byte IPv4 address. RDs disambiguate otherwise duplicate addresses in the same PE.

PEs understand the topology of each VPN, which are interconnected with MPLS tunnels, either directly or via P routers. In MPLS terminology, the P routers are Label Switch Routers without awareness of VPNs.

- Virtual router PPVPN

The virtual router architecture,[22][23] as opposed to BGP/MPLS techniques, requires no modification to existing routing protocols such as BGP. By the provisioning of logically independent routing domains, the customer operating a VPN is completely responsible for the address space. In the various MPLS tunnels, the different PPVPNs are disambiguated by their label, but do not need routing distinguishers.

Unencrypted tunnels

Some virtual networks use tunneling protocols without encryption for protecting the privacy of data. While VPNs often do provide security, an unencrypted overlay network does not neatly fit within the secure or trusted categorization. For example, a tunnel set up between two hosts with Generic Routing Encapsulation (GRE) is a virtual private network, but neither secure nor trusted.[24][25]

Native plaintext tunneling protocols include Layer 2 Tunneling Protocol (L2TP) when it is set up without IPsec and Point-to-Point Tunneling Protocol (PPTP) or Microsoft Point-to-Point Encryption (MPPE).[26]

Trusted delivery networks

Trusted VPNs do not use cryptographic tunneling, and instead rely on the security of a single provider's network to protect the traffic.[27]

- Multi-Protocol Label Switching (MPLS) often overlays VPNs, often with quality-of-service control over a trusted delivery network.

- Layer 2 Tunneling Protocol (L2TP)[28] which is a standards-based replacement, and a compromise taking the good features from each, for two proprietary VPN protocols: Cisco's Layer 2 Forwarding (L2F)[29] (obsolete as of 2009) and Microsoft's Point-to-Point Tunneling Protocol (PPTP).[30]

From the security standpoint, VPNs either trust the underlying delivery network, or must enforce security with mechanisms in the VPN itself. Unless the trusted delivery network runs among physically secure sites only, both trusted and secure models need an authentication mechanism for users to gain access to the VPN.

VPNs in mobile environments

Mobile virtual private networks are used in settings where an endpoint of the VPN is not fixed to a single IP address, but instead roams across various networks such as data networks from cellular carriers or between multiple Wi-Fi access points.[31] Mobile VPNs have been widely used in public safety, where they give law enforcement officers access to mission-critical applications, such as computer-assisted dispatch and criminal databases, while they travel between different subnets of a mobile network.[32] They are also used in field service management and by healthcare organizations,[33] among other industries.

Increasingly, mobile VPNs are being adopted by mobile professionals who need reliable connections.[33] They are used for roaming seamlessly across networks and in and out of wireless coverage areas without losing application sessions or dropping the secure VPN session. A conventional VPN can not withstand such events because the network tunnel is disrupted, causing applications to disconnect, time out,[31] or fail, or even cause the computing device itself to crash.[33]

Instead of logically tying the endpoint of the network tunnel to the physical IP address, each tunnel is bound to a permanently associated IP address at the device. The mobile VPN software handles the necessary network authentication and maintains the network sessions in a manner transparent to the application and the user.[31] The Host Identity Protocol (HIP), under study by the Internet Engineering Task Force, is designed to support mobility of hosts by separating the role of IP addresses for host identification from their locator functionality in an IP network. With HIP a mobile host maintains its logical connections established via the host identity identifier while associating with different IP addresses when roaming between access networks.

VPN on routers

With the increasing use of VPNs, many have started deploying VPN connectivity on routers for additional security and encryption of data transmission by using various cryptographic techniques.[34] Setting up VPN support on a router and establishing a VPN allows any networked device to have access to the entire network—all devices look like local devices with local addresses. Supported devices are not restricted to those capable of running a VPN client.[35]

Many router manufacturers, including Asus, Cisco, DrayTek,[35] Linksys, Netgear, and Yamaha, supply routers with built-in VPN clients. Some use open-source firmware such as DD-WRT, OpenWRT and Tomato, in order to support additional protocols such as OpenVPN.

Setting up VPN services on a router requires a deep knowledge of network security and careful installation. Minor misconfiguration of VPN connections can leave the network vulnerable. Performance will vary depending on the ISP.

Networking limitations

One major limitation of traditional VPNs is that they are point-to-point, and do not tend to support or connect broadcast domains. Therefore, communication, software, and networking, which are based on layer 2 and broadcast packets, such as NetBIOS used in Windows networking, may not be fully supported or work exactly as they would on a real LAN. Variants on VPN, such as Virtual Private LAN Service (VPLS), and layer 2 tunneling protocols, are designed to overcome this limitation.

See also

- Anonymizer

- Dynamic Multipoint Virtual Private Network

- Geo-blocking

- Internet privacy

- Mediated VPN

- Opportunistic encryption

- Split tunneling

- Tinc (protocol)

- UT-VPN

- Virtual private server

- VPNBook

References

- ↑ Crawford, Douglas (July 2017). "Five Best VPN Services in 2017.". BestVPN.com.

- ↑ Mason, Andrew G. (2002). Cisco Secure Virtual Private Network. Cisco Press. p. 7.

- ↑ Microsoft Technet. "Virtual Private Networking: An Overview".

- ↑ Ryan Browne (31 July 2017). "Russia follows China in tightening internet restrictions, raising fresh censorship concerns". CNBC.com. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- ↑ Cisco Systems, et al. Internet working Technologies Handbook, Third Edition. Cisco Press, 2000, p. 232.

- ↑ Lewis, Mark. Comparing, Designing. And Deploying VPNs. Cisco Press, 2006, p. 5

- ↑ International Engineering Consortium. Digital Subscriber Line 2001. Intl. Engineering Consortium, 2001, p. 40.

- ↑ Technet Lab. "IPv6 traffic over VPN connections". Archived from the original on 15 June 2012.

- ↑ RFC 6434, "IPv6 Node Requirements", E. Jankiewicz, J. Loughney, T. Narten (December 2011)

- ↑ SoftEther VPN: Using HTTPS Protocol to Establish VPN Tunnels

- ↑ "OpenConnect". Retrieved 2013-04-08.

OpenConnect is a client for Cisco's AnyConnect SSL VPN [...] OpenConnect is not officially supported by, or associated in any way with, Cisco Systems. It just happens to interoperate with their equipment.

- ↑ Trademark Applications and Registrations Retrieval (TARR)

- ↑ OpenBSD ssh manual page, VPN section

- ↑ Unix Toolbox section on SSH VPN

- ↑ Ubuntu SSH VPN how-to

- ↑ E. Rosen & Y. Rekhter (March 1999). "RFC 2547 BGP/MPLS VPNs". Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF).

- ↑ Lewis, Mark (2006). Comparing, designing, and deploying VPNs (1st print. ed.). Indianapolis, Ind.: Cisco Press. pp. 5–6. ISBN 1587051796.

- ↑ Ethernet Bridging (OpenVPN)

- ↑ Glyn M Burton: RFC 3378 EtherIP with FreeBSD, 03 February 2011

- ↑ net-security.org news: Multi-protocol SoftEther VPN becomes open source, January 2014

- ↑ Address Allocation for Private Internets, RFC 1918, Y. Rekhter et al., February 1996

- ↑ RFC 2917, A Core MPLS IP VPN Architecture

- ↑ RFC 2918, E. Chen (September 2000)

- ↑ "Overview of Provider Provisioned Virtual Private Networks (PPVPN)". Secure Thoughts. Retrieved 29 August 2016.

- ↑ RFC 1702: Generic Routing Encapsulation over IPv4 networks. October 1994.

- ↑ IETF (1999), RFC 2661, Layer Two Tunneling Protocol "L2TP"

- ↑ Cisco Systems, Inc. (2004). Internetworking Technologies Handbook. Networking Technology Series (4 ed.). Cisco Press. p. 233. ISBN 9781587051197. Retrieved 2013-02-15.

[...] VPNs using dedicated circuits, such as Frame Relay [...] are sometimes called trusted VPNs, because customers trust that the network facilities operated by the service providers will not be compromised.

- ↑ Layer Two Tunneling Protocol "L2TP", RFC 2661, W. Townsley et al., August 1999

- ↑ IP Based Virtual Private Networks, RFC 2341, A. Valencia et al., May 1998

- ↑ Point-to-Point Tunneling Protocol (PPTP), RFC 2637, K. Hamzeh et al., July 1999

- 1 2 3 Phifer, Lisa. "Mobile VPN: Closing the Gap", SearchMobileComputing.com, July 16, 2006.

- ↑ Willett, Andy. "Solving the Computing Challenges of Mobile Officers", www.officer.com, May, 2006.

- 1 2 3 Cheng, Roger. "Lost Connections", The Wall Street Journal, December 11, 2007.

- ↑ "Encryption and Security Protocols in a VPN". Retrieved 2015-09-23.

- 1 2 "VPN". Draytek. Retrieved 19 October 2016.

Further reading

- Kelly, Sean (August 2001). "Necessity is the mother of VPN invention". Communication News: 26–28. ISSN 0010-3632. Archived from the original on 2001-12-17.