Canton of Uri

| Kanton Uri | ||

|---|---|---|

| Canton of Switzerland | ||

| ||

Location in Switzerland | ||

|

Map of Uri  | ||

| Coordinates: 46°47′N 8°37′E / 46.783°N 8.617°ECoordinates: 46°47′N 8°37′E / 46.783°N 8.617°E | ||

| Capital | Altdorf | |

| Subdivisions | 20 municipalities | |

| Government | ||

| • Executive | Regierungsrat (7) | |

| • Legislative | Landrat (64) | |

| Area[1] | ||

| • Total | 1,076.57 km2 (415.67 sq mi) | |

| Population (12/2015)[2] | ||

| • Total | 35,973 | |

| • Density | 33/km2 (87/sq mi) | |

| ISO 3166 code | CH-UR | |

| Highest point | 3,630 m (11,909 ft): Dammastock | |

| Lowest point | 434 m (1,424 ft): Lake Lucerne | |

| Joined | 1291 | |

| Languages | German | |

| Website | UR.ch | |

The canton of Uri (German: Kanton ![]() Uri ) is one of the 26 cantons of Switzerland and a founding member of the Swiss Confederation. It is located in Central Switzerland. The canton's territory covers the valley of the Reuss between the St. Gotthard Pass and Lake Lucerne. The official language of Uri is (the Swiss variety of Standard) German, but the main spoken language is the Alemannic Swiss German dialect called Urner German. Uri was the only canton where the children in school had to learn Italian as their first foreign language. But in the school year of 2005/2006 this was changed to English as in most other cantons. The population is about 35,000 of which 3,046 (or 8.7%) are foreigners.[3] The legendary William Tell is said to have hailed from Uri. The historical landmark Rütli lies within the canton of Uri.

Uri ) is one of the 26 cantons of Switzerland and a founding member of the Swiss Confederation. It is located in Central Switzerland. The canton's territory covers the valley of the Reuss between the St. Gotthard Pass and Lake Lucerne. The official language of Uri is (the Swiss variety of Standard) German, but the main spoken language is the Alemannic Swiss German dialect called Urner German. Uri was the only canton where the children in school had to learn Italian as their first foreign language. But in the school year of 2005/2006 this was changed to English as in most other cantons. The population is about 35,000 of which 3,046 (or 8.7%) are foreigners.[3] The legendary William Tell is said to have hailed from Uri. The historical landmark Rütli lies within the canton of Uri.

Name

The name of the valley is first mentioned in the 8th or 9th century, in the Latinized form of Uronia.[4] In the medieval period, the name referred not to the entire Reuss valley but just to Altdorf and the surrounding settlements and estates. The extension of the name to a larger territory is the result of the territorial expansion of the canton in the 15th century. However, usage of Uri as referring to Altdorf remained current. From the 13th century onward, the German form of the name is recorded as Ure(n). The modern form Uri dates to the 16th century.

The name has been derived from either Latin ora "brim, edge, margin" (reflected as Rumantsch ur), or from a pre-Roman hydronym containing the PIE root u̯er "water", in either case extended by a suffix in -n-. Both etymologies would refer to the Reuss and/or the shore of Lake Lucerne. The -n- suffix was reduced to an ending in -n in Middle High German, and the ending -n in the German toponym was lost only in early modern German (remaining visible in the demonym Urner).[5]

There is a long-standing popular etymology associating the name with ûr, the German name of the aurochs. This tradition may date as far back as the Middle High German period, reflected in the introduction of the cantonal seal showing a bull's head in the 13th century. Beginning in the 17th century, the bull of Uri (Uristier) came to be associated with the name of the Taurisci in learned speculation.[5]

History

Early history

There are traces of settlement dating to the Bronze and Iron Age, with suggestions of trans-alpine trade with Quinto in Ticino and the alpine Rhine valley. During the Roman era, Uri remained mostly isolated from the Roman Empire. An analysis of the place names along the shores of Lake Lucerne show a Gallo-Roman influence, while in the mountain valleys Raetian names are more common. When the Roman Empire withdrew from the Alps, the lake side villages looked north to the towns along the lake for support, while the alpine villages in the Urseren valley banded together.[6]

Alemannic settlement begins in the 7th century. Uri is first mentioned in 732 as the place of banishment of Eto, the abbot of Reichenau, by the duke of Alamannia.[7] In 853, Uri is granted to the Fraumünster abbey in Zürich by Louis the German. Parts of the Urseren were settled by Disentis Abbey and were part of the Diocese of Chur. By the 10th century, there were settlements of Romansh speakers from Disentis in the high valleys.[6] Uri briefly passed under Habsburg rule in 1218, with the extinction of the Zähringer,. The Gotthard Pass was opened in 1230, and Uri was granted imperial immediacy by Henry VII in the following year. Trade across the Gotthard brought ever increasing wealth to Uri, and the towns and villages along the Gotthard route became increasing independent. As early as 1243 Uri had a district seal, and in 1274, Rudolph of Habsburg, who was now the Holy Roman Emperor, confirmed its privileges. Meanwhile, Urseren passed from Rapperswil to the Habsburgs in 1283.[6]

Since at least the 10th century, the people of Uri signed treaties as a collective, as nos inhabitantes Uroniam (955) or homines universi vallis Uranie (1273). By 1243, they used a seal with a bull's head.

Old Swiss Confederacy

A treaty of mutual recognition and assistance with Schwyz, possibly concluded in 1291 and certainly by 1309, would come to be regarded as the foundational act of the Old Swiss Confederacy or Eidgenossenschaft. The Battle of Morgarten in 1315, while of limited strategic importance, was the first instance of the Confererates defeating the Habsburgs in the field. A few months after the victory at Morgarten, the three Forest Cantons met at Brunnen to reaffirm their alliance in the Pact of Brunnen.[8] Over the following decades, the Confederacy expanded into the Acht Orte, now representing a regional power with the potential to challenge Habsburg hegemony. The Confederacy decisively defeated Habsburg in the Battle of Sempach 1386, opening the way to further territorial expansion.

Following the victory at Sempach, Uri began a program of territorial expansion to allow them to control the entire Gotthard route. As a first step, Uri annexed the Urseren valley in 1410, although the community of Urseren was allowed to retain its own assembly and courts. In 1403, Uri began to acquire its transmontane bailiwicks, with the help of Obwalden taking the Leventina valley from the duke of Milan. The conflict between the Swiss Confederacy and the Duchy of Milan for territories now forming canton of Ticino continued throughout the 15th century. The conflict was decided in 1500, when the Confederates captured Bellinzona, heavily fortifying it against future conquests. The Confederates also acquired Lugano in 1512, but the period of territorial expansion came to its end in 1515 with the Confederate defeat at Marignano.

Uri, along with Central Switzerland as a whole, resisted the Swiss Reformation and remained stauchly Catholic. As the Reformation spread through the Swiss Confederation, the five central, catholic cantons felt increasingly isolated and they began to search for allies. After two months of negotiations, the Five Cantons formed die Christliche Vereinigung (the Christian Alliance) with Ferdinand of Austria on 22 April 1529.[9][10] After the Battle at Kappel of 1531, in which Zwingli was killed, the Confederacy was on the point of fracturing along confessional lines. The peace treaty after the Kappel war established that each canton would choose which religion to follow, but peace between Catholic and Protestant cantons remained brittle throughout the early modern period.

Growth of Uri stagnated in the early modern period, due to the limited availability of arable land, as well as disease and crop failures. The plague broke out in the canton in 1348–49, 1517–18, 1574–75 and 1629. In 1742–43 and again 1770–71, crop failures combined with cattle diseases led to starvation and mass emigration. The consequences for the population were severe, in 1743 Uri had 9,828 inhabitants, but by the end of the 18th Century there were only 9,464 people.[6]

Modern history

The government of Uri spoke out against the ideals of the French Revolution and opposed any attempt to institute changes in Switzerland. In January 1798, French revolutionary forces invaded Switzerland. On 11 April the victorious French announced the creation of the Helvetic Republic and gave the cantons twelve days to accept the new constitution. The cantons of Central Switzerland attempted to resist, but the uprising was suppressed and on 5 May Uri agreed to accept the Helvetic Republic. The cantonal army was disarmed in September and the canton was occupied by French troops in October.[6] Under the Helvetic Republic, Uri was part of the Canton of Waldstätten, along with Zug, Obwalden, Nidwalden and the inner portions of Schwyz. The Leventina valley was given to the newly formed Canton of Ticino, stripping Uri of all possessions south of the Gotthard. In April and May 1799, Franz Vincenz Schmid led an unsuccessful uprising against the occupying French army.

From June until the end of September 1799, troops of the Second Coalition fought the French in Uri. With the defeat of the Russian general Alexander Korsakov at the Second Battle of Zürich, the only other Coalition army, under Alexander Suvorov, was forced to retreat out of Switzerland though the alps in winter. The damage from fighting, Suvorov's retreat and other disasters (including a fire that destroyed much of Altdorf in 1799) caused a famine in Uri. Although the government commissioner, Heinrich Zschokke, organized a relief effort to prevent starvation, it took years for Uri to repair the damage to the villages and towns. In October 1801, a new government came to power in the Helvetic Republic and in early November the Canton of Waldstätten was dissolved and Uri became a canton again. The governor, Josef Anton von Beroldingen, attempted unsuccessfully to bring the Leventina valley back into Uri. Half a year later, on 17 April 1802, the Unitarian party took power back in the Republic and revised the constitution once again. In early June, Uri rejected the newest constitution while at the same time French troops withdrew from Switzerland. Without the French army to suppress them, Uri and other rural populations successfully rebelled against the government in the Stecklikrieg. In response to the collapse of the Helvetic Republic, Napoleon issued the Act of Mediation in 1803. As part of the Act of Mediation, Uri regained its independence and all attempts towards religious or constitutional reform were resisted.[6] After the invasion of the Sixth Coalition into Switzerland on 29 December 1813, the Act of Mediation lost its power. While the neighbouring cantons of Schwyz and Nidwalden wanted to return to the organization of the Old Swiss Confederation, Uri was part of the Zürich-led party, which sought to reorganize the 19 cantons created by the Act. Uri also attempted, unsuccessful, to reincorporate the Leventina valley, but was only able to receive the rights to one-half of the taxes on all trade over Monte Piottino into the Leventina. On 5 May 1815 the Landsgemeinde approved the federal constitution. Uri then mediated between the Tagsatzung and Nidwalden, which had refused to recognize the treaty.

Uri remained without an official constitution until 1820. The document included only six principles that were based on traditional practice and existing state laws. The government remained deeply conservative during the Restoration period. Discontent with the cantonal government collected until 1834 when a reform party demanded a number of liberal constitutional changes. The Landsgemeinde, however, rejected these calls for reform. In the 1840s, urban, Protestant liberals gained the majority in the Tagsatzung and proposed a new constitution. To protect their traditional religion and power structure, the seven conservative, catholic cantons formed a separate alliance or Sonderbund in 1843. In 1847, the Sonderbund broke with the Federal Government and the Sonderbund War broke out. During the conflict, Uri sent troops to participate in the fighting along the Reuss-Emme defensive line as well as on the foray over the Gotthard into Ticino. After the defeat of the Sonderbund troops in Gisikon on 23 November 1847 Uri withdrew from the alliance and surrendered on 28 November 1847. Two days later federal troops moved into Uri.

After the defeat of the Sonderbund, Uri supported the new Swiss Federal Constitution. They established a cantonal constitution that included some liberal changes including; the abolition of lifetime alderman positions, eliminating the privy council and secret council meetings and the establishment of a provisional executive council. The Landsgemeinde was the supreme sovereign power. The Catholic Church continued to enjoy privileges, but freedom of worship was now available for other faiths. The new Federal Constitution of 1874, which was rejected by the voters of Uri, led to a total revision of the cantonal constitution in 1888. The new constitution streamlined the government and addressed many of the issues of the 1848 cantonal constitution. The Landsgemeinde continued to meet on a local level until the last one was held in Bötzlingen in the municipality of Schattdorf on 6 May 1928.[11] The Christian Democratic Party (CVP) and the Free Democratic Party (FDP) have dominated politics in Uri during the 20th century.[6]

Geography

The canton is located in the centre of the country on the north side of the Swiss Alps. The lands of the canton are that of the Reuss valley and those of the main river's tributaries. Uri has an area, as of 2011, of 1,076.4 km2 (415.6 sq mi). Of this area, 24.4% is used for agricultural purposes, while 18.2% is forested. Of the rest of the land, 1.7% is settled (buildings or roads) and 55.6% is unproductive land.[12]

The highest elevation in the canton, and in the Urner Alps as a whole, is the Dammastock, at 3,630 m (11,910 ft), north of the Furka Pass. The Glarus and Lepontine Alps ranges are also partially situated in the canton of Uri.

Administrative divisions

Uri today comprises 20 self-administered territories: the cantonal capital is Altdorf.

The municipalities of the canton of Uri are: Altdorf, Andermatt, Attinghausen, Bauen, Bürglen, Erstfeld, Flüelen, Göschenen, Gurtnellen, Hospental, Isenthal, Realp, Schattdorf, Seedorf, Seelisberg, Silenen, Sisikon, Spiringen, Unterschächen, Wassen

Flag and coat of arms

The blazon of the coat of arms is Or, a bull's head caboshed sable, langued and noseringed gules.[14]

The use of the bull's head as heraldic charge may be due to a popular etymology associating the canton's name with the name of the aurochs.[5] It is certain that such an association was made in the early modern period; the introduction of the bull as heraldic animal dates to the 13th century. Uri used a seal with a bull's head, seen from the side, by 1243. By the 14th century, Uri was using a banner showing a black bull's head in a yellow field. In the town-hall of Altfdorf, six cantonal banners dating to the Old Swiss Confederacy are preserved, reportedly dating from the battles of Morgarten (1315) and Sempach (1386), the Old Zürich War (1443), the Burgundian Wars (1476) and the Swabian War (1499), and the Juliusbanner (1512).[13]

Demographics

Uri has a population (as of December 2015) of 35,973.[15] As of 2010, 9.4% of the population are resident foreign nationals. Over the last 10 years (2000–2010) the population has changed at a rate of −0.4%. Migration accounted for −1.2%, while births and deaths accounted for 1.3%.[12] Most of the population (as of 2000) speaks German (32,518 or 93.5%) as their first language, Serbo-Croatian is the second most common (677 or 1.9%) and Italian is the third (462 or 1.3%). There are 67 people who speak French and 51 people who speak Romansh.[16]

Of the population in the canton, 16,481 or about 47.4% were born in Uri and lived there in 2000. There were 9,118 or 26.2% who were born in the same canton, while 5,426 or 15.6% were born somewhere else in Switzerland, and 3,019 or 8.7% were born outside of Switzerland.[16] As of 2000, children and teenagers (0–19 years old) make up 25% of the population, while adults (20–64 years old) make up 58.6% and seniors (over 64 years old) make up 16.4%.[12] As of 2000, there were 15,029 people who were single and never married in the canton. There were 16,839 married individuals, 2,040 widows or widowers and 869 individuals who are divorced.[16]

As of 2000, there were 13,430 private households in the canton, and an average of 2.5 persons per household.[12] There were 3,871 households that consist of only one person and 1,382 households with five or more people. As of 2009, the construction rate of new housing units was 4.7 new units per 1000 residents.[12] The vacancy rate for the canton, in 2010, was 0.77%.[12]

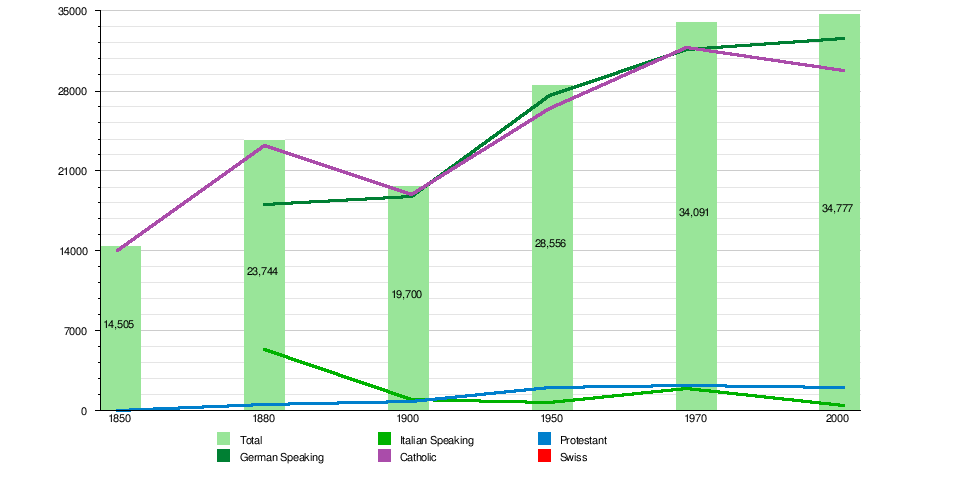

The historical population is given in the following chart:[6]

| Historic Population Data[6] | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Total Population | German Speaking | Italian Speaking | Catholic | Protestant | Other | Jewish | Christian Catholic | No religion given | Swiss | Non-Swiss |

| 1850 | 14,505 | 14,493 | 12 | 14 465 | 40 | ||||||

| 1860 | 14,741 | ||||||||||

| 1870 | 16,095 | ||||||||||

| 1880 | 23,744 | 18,024 | 5,313 | 23,149 | 524 | 21 | 7 | 17 376 | 6 368 | ||

| 1888 | 17,249 | ||||||||||

| 1900 | 19,700 | 18,685 | 947 | 18,924 | 773 | 3 | 1 | 18 267 | 1 433 | ||

| 1910 | 22,113 | ||||||||||

| 1920 | 23,973 | ||||||||||

| 1930 | 22,968 | ||||||||||

| 1941 | 27,302 | ||||||||||

| 1950 | 28,556 | 27,639 | 693 | 26,439 | 2,073 | 24 | 20 | 27 743 | 813 | ||

| 1960 | 32,021 | ||||||||||

| 1970 | 34,091 | 31,546 | 1,900 | 31,732 | 2,236 | 113 | 10 | 31 | 31 393 | 2 698 | |

| 1980 | 33,883 | ||||||||||

| 1990 | 34,208 | ||||||||||

| 2000 | 34,777 | 32,518 | 462 | 29,846 | 2,074 | 2,835 | 7 | 22 | 818 | 31 706 | 3 071 |

Economy

The cultivated fields of the canton are located in the valley of the Reuss. There are pastures on the lower mountain slopes. Since most of the terrain is extremely hilly, it is not suitable for cultivation. Hydroelectric power generation is of great importance. Forestry is one of the most important sectors of agriculture. At Altdorf there are cable and rubber factories.

Tourism is an important source of income in the canton of Uri. An excellent network of roads facilitates tourism in remote areas in the mountains.

As of 2010, Uri had an unemployment rate of 1.4%. As of 2008, there were 1,764 people employed in the primary economic sector and about 703 businesses involved in this sector. 5,388 people were employed in the secondary sector and there were 324 businesses in this sector. 9,431 people were employed in the tertiary sector, with 1,113 businesses in this sector.[12]

In 2008 the total number of full-time equivalent jobs was 13,383. The number of jobs in the primary sector was 958, of which 891 were in agriculture, 65 were in forestry or lumber production and 1 was in fishing or fisheries. The number of jobs in the secondary sector was 5,078 of which 2,948 or (58.1%) were in manufacturing, 71 or (1.4%) were in mining and 1,696 (33.4%) were in construction. The number of jobs in the tertiary sector was 7,347. In the tertiary sector; 1,384 or 18.8% were in the sale or repair of motor vehicles, 819 or 11.1% were in the movement and storage of goods, 1,126 or 15.3% were in a hotel or restaurant, 103 or 1.4% were in the information industry, 264 or 3.6% were the insurance or financial industry, 445 or 6.1% were technical professionals or scientists, 505 or 6.9% were in education and 1,505 or 20.5% were in health care.[17]

Of the working population, 12.1% used public transportation to get to work, and 48.5% used a private car.[12]

Tourism

There are 39 cable cars in the valley which provide access to numerous peaks, hiking and bike trails as well as ski slopes and cross-country tracks.[18]

Tourism is a major industry in the Canton of Uri. In 2008, there were 91 hotels in the canton with a total of 1,368 rooms. During the same year 145,600 guests stayed in those hotels and 67.1% were from outside Switzerland.[19]

The Canton of Uri is named as erstwhile home of "Heinz the Baron Claus Von Espy" in American 2003 movie, "Intolerable Cruelty", produced by the Coen Brothers.

Politics

Federal election

In the 2015 federal election the most popular party was the SVP/UDC which received 44.1% of the vote. The next most popular parties were the CVP/PDC/PPD/PCD with 26.8% and the GPS/PES with 26.3%.[20]

In the 2011 federal election the most popular party was the FDP which received 74.3% of the vote. The next most popular party was the SP/PS (21.5%). The remainder of the vote (4.3%) was split between other local parties.[21]

The FDP lost about 13.0% of the vote when compared to the 2007 Federal election (87.3% in 2007 vs 74.3% in 2011). The SP/PS moved from below fourth place in 2007 to second.[22]

Federal election results

| Percentage of the total vote per party in the canton in the Federal Elections 1971-2015[20] | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Ideology | 1971 | 1975 | 1979 | 1983 | 1987 | 1991 | 1995 | 1999 | 2003 | 2007 | 2011 | 2015 | |

| FDP.The Liberalsa | Classical liberalism | 95.2 | 76.0 | 39.0 | 84.7 | 85.5 | 93.2 | 86.0 | 81.7 | 36.6 | 87.3 | 74.3 | * | |

| CVP/PDC/PPD/PCD | Christian democracy | * b | 18.6 | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 26.8 | |

| SP/PS | Social democracy | * | * | 23.0 | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 21.5 | * | |

| SVP/UDC | Swiss nationalism | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 31.3 | * | * | 44.1 | |

| GPS/PES | Green politics | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 30.6 | * | * | 26.3 | |

| FPS/PSL | Right-wing populism | * | * | * | * | 1.7 | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | |

| Other | 4.8 | 5.4 | 38.0 | 15.3 | 12.8 | 6.8 | 14.0 | 18.3 | 1.5 | 12.7 | 4.3 | 2.8 | ||

| Voter participation % | 56.1 | 47.3 | 56.2 | 30.0 | 46.2 | 34.6 | 39.7 | 36.3 | 44.4 | 24.1 | 49.8 | 57.1 | ||

- ^a FDP before 2009, FDP.The Liberals after 2009

- ^b "*" indicates that the party was not on the ballot in this canton.

Cantonal election

In the last election, on 11 March 2012, saw the centre maintain its dominance of the Landsrat. The Christian Democrats (CVP) lost one seat, but remained the largest party with 23. The Swiss People's Party lost four seats to become tied for second with the FDP.The Liberals who had gained two. Both parties held 14 seats. The retained 10 seats but dropped to the third largest. The Social Democratic Party (SP) and the Green Party are listed together in the canton. The combined SP/Green gained one seat and remained the fourth largest party with 11 total. The final seat was held by an unaffiliated candidate. The final seat will remain vacant until the 15 April 2012 second election.[23]

| Party | Ideology | Seats | Seats ± | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Christian Democratic People's Party | Christian democracy | 23 | -1 | ||

| FDP.The Liberals | Classical liberalism | 14 | +2 | ||

| Social Democratic Party/Green Party | Social democracy/Green politics | 11 | +1 | ||

| Swiss People's Party | National conservatism | 14 | -4 | ||

| Unaffiliated | N/A | 1 | +1 | ||

| Total | 63 | – | |||

| Source: Canton of Uri | |||||

The evolving party membership in the Landrat is shown in the following chart (for selected dates):[6][23]

Religion

From the 2000 census, 29,846 or 85.8% were Roman Catholic, while 1,809 or 5.2% belonged to the Swiss Reformed Church. Of the rest of the population, there were 525 members of an Orthodox church (or about 1.51% of the population), there were 22 individuals (or about 0.06% of the population) who belonged to the Christian Catholic Church, and there were 565 individuals (or about 1.62% of the population) who belonged to another Christian church. There were 7 individuals (or about 0.02% of the population) who were Jewish, and 683 (or about 1.96% of the population) who were Islamic. There were 44 individuals who were Buddhist, 46 individuals who were Hindu and 22 individuals who belonged to another church. 818 (or about 2.35% of the population) belonged to no church, are agnostic or atheist, and 655 individuals (or about 1.88% of the population) did not answer the question.[16]

Education

In Uri about 11,949 or (34.4%) of the population have completed non-mandatory upper secondary education, and 2,794 or (8.0%) have completed additional higher education (either university or a Fachhochschule). Of the 2,794 who completed tertiary schooling, 74.2% were Swiss men, 16.9% were Swiss women, 5.7% were non-Swiss men and 3.3% were non-Swiss women.[16]

References

- ↑ Arealstatistik Standard - Kantonsdaten nach 4 Hauptbereichen

- ↑ Swiss Federal Statistical Office - STAT-TAB, online database – Ständige und nichtständige Wohnbevölkerung nach institutionellen Gliederungen, Geburtsort und Staatsangehörigkeit (in German) accessed 30 August 2016

- ↑ Federal Department of Statistics (2008). "Ständige Wohnbevölkerung nach Staatsangehörigkeit, Geschlecht und Kantonen" (Microsoft Excel). Retrieved 5 November 2008.

- ↑ The oldest mention of the name is in a document dated 853, as pagus uroniae. Some Middle Latin sources also spell Urania. There is a possible mention dating to the 8th century, in the context of the banishment of abbot Eto to Uri in 732, but this is extant only in an 11th-century chronicle ( Eto, Augiae abbas, a Theodebaldo ob odium Karoli in Uraniam relegatus Hermannus Contractus, Chronicum, c. 1040).

- 1 2 3 Albert Hug, Viktor Weibel: Urner Namenbuch. Die Orts- und Flurnamen des Kantons Uri, Altdorf 1990, Band 3, Seite 768 ff. bzw. Uri unter ortsnamen.ch

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Uri in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

- ↑

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Uri". Encyclopædia Britannica. 27 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 795–796.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Uri". Encyclopædia Britannica. 27 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 795–796. - ↑ Battle of Morgarten in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

- ↑ Gäbler, Ulrich (1986), Huldrych Zwingli: His Life and Work, Philadelphia: Fortress Press, pp. 119–120, ISBN 0-8006-0761-9

- ↑ Potter, G. R. (1976), Zwingli, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 352–355, ISBN 0-521-20939-0

- ↑ History of Schattdorf Archived 20 April 2006 at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Swiss Federal Statistical Office accessed 5 January 2012

- 1 2 Muheim Hans, Das Rathaus von Uri in Altdorf (Kunstführer, Gesellschaft für Schweizerische Kunstgeschichte), Bern, 1989 (urikon.ch Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine.).

- ↑ Flags of the World.com accessed 5 January 2012

- ↑ Swiss Federal Statistical Office - STAT-TAB, online database – Ständige und nichtständige Wohnbevölkerung nach institutionellen Gliederungen, Geburtsort und Staatsangehörigkeit (in German) accessed 30 August 2016

- 1 2 3 4 5 STAT-TAB Datenwürfel für Thema 40.3 – 2000 Archived 9 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine. (in German) accessed 2 February 2011

- ↑ Swiss Federal Statistical Office STAT-TAB Betriebszählung: Arbeitsstätten nach Gemeinde und NOGA 2008 (Abschnitte), Sektoren 1–3 Archived 25 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine. (in German) accessed 28 January 2011

- ↑ List of cable cars in Uri Archived 18 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Canton of Uri Statistics-Angebot, Ankünfte und Logiernächte in Hotelbetrieben Uri (2005 bis 2008) (in German) accessed 15 January 2012

- 1 2 Nationalratswahlen: Stärke der Parteien nach Kantonen (Schweiz = 100%) (Report). Swiss Federal Statistical Office. 2015.

- ↑ Swiss Federal Statistical Office, Elections in Switzerland (in German) accessed 5 January 2012

- ↑ Swiss Federal Statistical Office, Nationalratswahlen 2007: Stärke der Parteien und Wahlbeteiligung, nach Gemeinden/Bezirk/Canton Archived 14 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine. (in German) accessed 28 May 2010

- 1 2 Wahl des Landrats – Zusammenfassung: Resultate aus 20 Gemeinden from Uri Cantonal election webpage (in German) accessed 21 March 2012

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Canton of Uri. |

- Official site (in German)

- Official statistics