Urban design

Urban design is the process of designing and shaping cities, towns and villages. In contrast to architecture, which focuses on the design of individual buildings, urban design deals with the larger scale of groups of buildings, streets and public spaces, whole neighborhoods and districts, and entire cities, with the goal of making urban areas functional, attractive, and sustainable.[1]

Urban design is an inter-disciplinary subject that utilizes elements of many built environment professions, including landscape architecture, urban planning, architecture, civil and municipal engineering.[2] It is common for professionals in all these disciplines to practice in urban design. In more recent times different sub-strands of urban design have emerged such as strategic urban design, landscape urbanism, water-sensitive urban design, and sustainable urbanism.

Urban design demands an understanding of a wide range of subjects from physical geography to social science, and an appreciation for disciplines, such as real estate development, urban economics, political economy and social theory.

Urban design is about making connections between people and places, movement and urban form, nature and the built fabric. Urban design draws together the many strands of place-making, environmental stewardship, social equity and economic viability into the creation of places with distinct beauty and identity. Urban design draws these and other strands together creating a vision for an area and then deploying the resources and skills needed to bring the vision to life.

Urban design theory deals primarily with the design and management of public space (i.e. the 'public environment', 'public realm' or 'public domain'), and the way public places are experienced and used. Public space includes the totality of spaces used freely on a day-to-day basis by the general public, such as streets, plazas, parks and public infrastructure. Some aspects of privately owned spaces, such as building facades or domestic gardens, also contribute to public space and are therefore also considered by urban design theory. Important writers on urban design theory include Christopher Alexander, Peter Calthorpe, Gordon Cullen, Andres Duany, Jane Jacobs, Mitchell Joachim, Jan Gehl, Allan B. Jacobs, Kevin Lynch, Aldo Rossi, Colin Rowe, Robert Venturi, William H. Whyte, Camillo Sitte, Bill Hillier (Space syntax) and Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk.

History

Although contemporary professional use of the term 'urban design' dates from the mid-20th century, urban design as such has been practiced throughout history. Ancient examples of carefully planned and designed cities exist in Asia, Africa, Europe and the Americas, and are particularly well-known within Classical Chinese, Roman and Greek cultures (see Hippodamus of Miletus).

European Medieval cities are often, and often erroneously, regarded as exemplars of undesigned or 'organic' city development. There are many examples of considered urban design in the Middle Ages (see, e.g., David Friedman, Florentine New Towns: Urban Design in the Late Middle Ages, MIT 1988). In England, many of the towns listed in the 9th century Burghal Hidage were designed on a grid, examples including Southampton, Wareham, Dorset and Wallingford, Oxfordshire, having been rapidly created to provide a defensive network against Danish invaders. 12th century western Europe brought renewed focus on urbanisation as a means of stimulating economic growth and generating revenue. The burgage system dating from that time and its associated burgage plots brought a form of self-organising design to medieval towns. Rectangular grids were used in the Bastides of 13th and 14th century Gascony, and the new towns of England created in the same period.

Throughout history, design of streets and deliberate configuration of public spaces with buildings have reflected contemporaneous social norms or philosophical and religious beliefs (see, e.g., Erwin Panofsky, Gothic Architecture and Scholasticism, Meridian Books, 1957). Yet the link between designed urban space and human mind appears to be bidirectional. Indeed, the reverse impact of urban structure upon human behaviour and upon thought is evidenced by both observational study and historical record. There are clear indications of impact through Renaissance urban design on the thought of Johannes Kepler and Galileo Galilei (see, e.g., Abraham Akkerman, "Urban planning in the founding of Cartesian thought," Philosophy and Geography 4(1), 2001). Already René Descartes in his Discourse on the Method had attested to the impact Renaissance planned new towns had upon his own thought, and much evidence exists that the Renaissance streetscape was also the perceptual stimulus that had led to the development of coordinate geometry (see, e.g., Claudia Lacour Brodsky, Lines of Thought: Discourse, Architectonics, and the Origins of Modern Philosophy, Duke 1996).

The beginnings of modern urban design in Europe are associated with the Renaissance but, especially, with the Age of Enlightenment. Spanish colonial cities were often planned, as were some towns settled by other imperial cultures. These sometimes embodied utopian ambitions as well as aims for functionality and good governance, as with James Oglethorpe's plan for Savannah, Georgia. In the Baroque period the design approaches developed in French formal gardens such as Versailles were extended into urban development and redevelopment. In this period, when modern professional specialisations did not exist, urban design was undertaken by people with skills in areas as diverse as sculpture, architecture, garden design, surveying, astronomy, and military engineering. In the 18th and 19th centuries, urban design was perhaps most closely linked with surveyors (engineers) and architects. The increase in urban populations brought with it problems of epidemic disease, the response to which was a focus on public health, the rise in the UK of municipal engineering and the inclusion in British legislation of provisions such as minimum widths of street in relation to heights of buildings in order to ensure adequate light and ventilation.

Much of Frederick Law Olmsted's[3] work was concerned with urban design, and the newly formed profession of landscape architecture also began to play a significant role in the late 19th century.

Modern urban design

Urban planning focuses on public health and urban design. Within the discipline, modern urban design developed.

At the turn of the 20th century, planning and architecture underwent a paradigm shift because of societal pressures. During this time, cities were industrializing at a tremendous rate; private business largely dictated the pace and style of this development. The expansion created many hardships for the working poor and concern for health and safety increased. However, the laissez-faire style of government, in fashion for most of the Victorian era, was starting to give way to a New Liberalism. This gave more power to the public. The public wanted the government to provide citizens, especially factory workers, with healthier environments. Around 1900, modern urban design emerged from developing theories on how to mitigate the consequences of the industrial age.

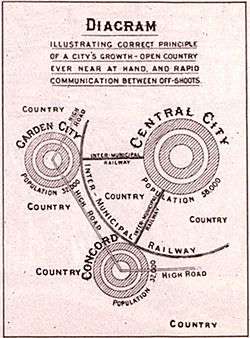

The first modern urban planning theorist was Sir Ebenezer Howard. His ideas, although utopian, were adopted around the world because they were highly practical. He initiated the garden city movement in 1898 garden city movement.[4] His garden cities were intended to be planned, self-contained communities surrounded by parks. Howard wanted the cities to be proportional with separate areas of residences, industry, and agriculture. Inspired by the Utopian novel Looking Backward and Henry George's work Progress and Poverty, Howard published his book Garden Cities of To-morrow in 1898. His work is commonly regarded as the most important book in the history of urban planning.[5] He envisioned the self-sufficient garden city to house 32,000 people on a site 6,000 acres (2,428 ha). He planned on a concentric pattern with open spaces, public parks, and six radial boulevards, 120 ft (37 m) wide, extending from the center. When it reached full population, Howard wanted another garden city to be developed nearby. He envisaged a cluster of several garden cities as satellites of a central city of 50,000 people, linked by road and rail.[6] His model for a garden city was first created at Letchworth[7] and Welwyn Garden City in Hertfordshire. Howard’s movement was extended by Sir Frederic Osborn to regional planning.[8]

In the early 1900s, urban planning became professionalized. With input from utopian visionaries, infrastructure engineers, and local councilors, new urban planning templates were made to be considered by politicians. In 1899, the Town and Country Planning Association was founded. In 1909, the first academic course on urban planning was offered by the University of Liverpool.[9] Urban planning was first officially embodied in the Housing and Town Planning Act of 1909 Howard’s ‘garden city’ compelled local authorities to introduce a system where all housing construction conformed to specific building standards.[10] In the United Kingdom following this Act, surveyor, civil engineers, architects, and lawyers began working together within local authorities. In 1910, Thomas Adams became the first Town Planning Inspector at the Local Government Board and began meeting with practitioners. In 1914, The Town Planning Institute was established. The first urban planning course in America wasn’t established until 1924 at Harvard University. Professionals developed schemes for the development of land, transforming town planning into a new area of expertise.

In the 20th century, urban planning was forever changed by the automobile industry. Car oriented design impacted the rise of ‘urban design’. City layouts now had to revolve around roadways and traffic patterns. In 1956, 'Urban design' was first used at a series of conferences Harvard University. The event provided a platform for Harvard’s Urban Design program. The program also utilized the writings of famous urban planning thinkers: Gordon Cullen, Jane Jacobs, Kevin Lynch, and Christopher Alexander.

In 1961, Gordon Cullen published The Concise Townscape. He examined the traditional artistic approach to city design of theorists including Camillo Sitte, Barry Parker and Raymond Unwin. Cullen also created the concept of 'serial vision'. It defined the urban landscape as a series of related spaces.

In 1961, Jane Jacobs published ' The Death and Life of Great American Cities. She critiqued the Modernism of CIAM (International Congresses of Modern Architecture). Jacobs also crime rates in publicly owned spaces were rising because of the Modernist approach of ‘city in the park’. She argued instead for an 'eyes on the street' approach to town planning through the resurrection of main public space precedents (e.g. streets, squares).

In the same year, Kevin Lynch published The Image of the City. He was seminal to urban design, particularly with regards to the concept of legibility. He reduced urban design theory to five basic elements: paths, districts, edges, nodes, landmarks. He also made the use of mental maps to understanding the city popular, rather than the two-dimensional physical master plans of the previous 50 years.

Other notable works:

Architecture of the City by Rossi (1966)

Learning from Las Vegas by Venturi (1972)

Collage City by Colin Rowe(1978)

The Next American Metropolis by Peter Calthorpe(1993)

The Social Logic of Space by Bill Hillier and Julienne Hanson (1984)

The popularity of these works resulted in terms that become everyday language in the field of urban planning. Aldo Rossi introduced 'historicism' and 'collective memory' to urban design. Rossi also proposed a 'collage metaphor' to understand the collection of new and old forms within the same urban space. Peter Calthorpe developed a manifesto for sustainable urban living via medium density living. He also designed a manual for building new settlements in his concept of Transit Oriented Development (TOD). Bill Hillier and Julienne Hanson introduced Space Syntax to predict how movement patterns in cities would contribute to urban vitality, anti-social behaviour and economic success. 'Sustainability', 'livability', and 'high quality of urban components' also became commonplace in the field.

Current trends

Urban design seeks to create sustainable urban environments with long-lasting structures, buildings and overall livability. walkable urbanism is another ideal that is defined as the Charter of New Urbanism. It aims to reduce environmental impacts by altering the built environment to create smart cities that support sustainable transport.[1] Compact urban neighborhoods encourage residents to drive less. These neighborhoods have significantly lower environmental impacts when compared to sprawling suburbs.[11] To prevent urban sprawl, Circular flow land use management was introduced in Europe to promote sustainable land use patterns.

As a result of the recent New Classical Architecture movement, sustainable construction aims to develop smart growth, walkability, architectural tradition, and classical design.[12][13] It contrasts from modernist and globally uniform architecture. In the 1980s, urban design began to oppose the increasing solitary housing estates and suburban sprawl.[14]

Principles

Public agencies, authorities, and the interests of nearby property owners manage public spaces. Users often compete over the spaces and negotiate across a variety of spheres. Urban designers lack control in the design profession; this is offered to architects. Input from engineers, ecologists, local historians, and transportation planners is required to offer a balanced representation of ideas.

Urban designers are similar to urban planners when preparing design guidelines, regulatory frameworks, legislation, advertising, etc. Urban planners also overlap with architects, landscape architects, transportation engineers and industrial designers. They must also deal with ‘place management’ to guide and assist the use and maintenance of urban areas and public spaces.

There are professionals who identify themselves specifically as urban designers. However, architecture, landscape and planning programs incorporate urban design theory and design subjects into their curricula. There are an increasing number of university programs offering degrees in urban design at post-graduate level.

Urban design considers:

- Pedestrian zones

- Incorporation of nature within a city

- Aesthetics

- Urban structure – arrangement and relation of business and people

- Urban typology, density and sustainability - spatial types and morphologies related to intensity of use, consumption of resources and production and maintenance of viable communities

- Accessibility – safe and easy transportation

- Legibility and wayfinding – accessible information about travel and destinations

- Animation – Designing places to stimulate public activity

- Function and fit – places support their varied intended uses

- Complementary mixed uses – Locating activities to allow constructive interaction between them

- Character and meaning – Recognizing differences between places

- Order and incident – Balancing consistency and variety in the urban environment

- Continuity and change – Locating people in time and place, respecting heritage and contemporary culture

- Civil society – people are free to interact as civic equals, important for building social capital

Equality issues

Until the 1970s, the design of towns and cities took little account of the needs of people with disabilities. At that time, disabled people began to form movements demanding recognition of their potential contribution if social obstacles were removed. Disabled people challenged the 'medical model' of disability which saw physical and mental problems as an individual 'tragedy' and people with disabilities as 'brave' for enduring them. They proposed instead a 'social model' which said that barriers to disabled people result from the design of the built environment and attitudes of able-bodied people. 'Access Groups' were established composed of people with disabilities who audited their local areas, checked planning applications and made representations for improvements. The new profession of 'access officer' was established around that time to produce guidelines based on the recommendations of access groups and to oversee adaptations to existing buildings as well as to check on the accessibility of new proposals. Many local authorities now employ access officers who are regulated by the Access Association. A new chapter of the Building Regulations (Part M) was introduced in 1992. Although it was beneficial to have legislation on this issue the requirements were fairly minimal but continue to be improved with ongoing amendments. The Disability Discrimination Act 1995 continues to raise awareness and enforce action on disability issues in the urban environment.

See also

References

- 1 2 Boeing; et al. (2014). "LEED-ND and Livability Revisited". Berkeley Planning Journal. 27: 31–55. Retrieved 2015-04-15.

- ↑ Van Assche, K., Beunen, R., Duineveld, M., & de Jong, H. (2013). Co-evolutions of planning and design: Risks and benefits of design perspectives in planning systems. Planning Theory, 12(2), 177-198.

- ↑ "Frederick Law Olmsted". fredericklawolmsted.com.

- ↑ Peter Hall, Mark Tewdwr-Jones (2010). Urban and Regional Planning. Routledge.

- ↑ "To-morrow: A Peaceful Path to Real Reform".

- ↑ Goodall, B (1987), Dictionary of Human Geography, London: Penguin.

- ↑ Hardy 1999, p. 4.

- ↑ History 1899–1999 (PDF), TCPA.

- ↑ "urban planning".

- ↑ "The birth of town planning".

- ↑ Ewing, R "Growing Cooler - the Evidence on Urban Development and Climate Change". Retrieved on: 2009-03-16.

- ↑ Charter of the New Urbanism

- ↑ "Beauty, Humanism, Continuity between Past and Future". Traditional Architecture Group. Retrieved 23 March 2014.

- ↑ Issue Brief: Smart-Growth: Building Livable Communities. American Institute of Architects. Retrieved on 2014-03-23.

Further reading

- Barnett, Jonathan, An Introduction to Urban Design, Harper & Row, New York 1982, ISBN 0-06-430376-4

- Carmona, Matthew, and Tiesdell, Steve, editors, Urban Design Reader, Architectural Press of Elsevier Press, Amsterdam Boston other cities 2007, ISBN 0-7506-6531-9

- Foroughmand Araabi, Hooman. "A typology of Urban Design theories and its application to the shared body of knowledge" Urban Design International 21.1 (2016): 11-24.

- Hardinghaus, Matthias, 'Learning Outcomes and Assessment Criteria in Urban Design: A Problematisation of Spatial Thinking', Cebe Transaction, The Online Journal of the Centre for Education in the Built Environment, 2006, 3(2), 9-22

- Larice, Michael, and MacDonald, Elizabeth, editors, The Urban Design Reader, Routledge, New York London 2007, ISBN 0-415-33386-5

- Hillier B. and Hanson J. "The Social Logic of Space". Cambridge University Press, 1984. ISBN 0-521-36784-0.

- David Gosling, Barry Maitland, Concepts of urban design, University of Minnesota 1984, ISBN 0-312-16121-2.

- Aseem Inam, Designing Urban Transformation, New York and London: Routledge, 2013 (ISBN 978-0415837705).

- Van Assche, K., Beunen, R., Duineveld, M., & de Jong, H. "Co-evolutions of planning and design: Risks and benefits of design perspectives in planning systems". 2013 Planning Theory, 12(2), 177-198.