Panthera leo spelaea

| Panthera leo spelaea Temporal range: Middle Pleistocene to Early Holocene, 1.3–0.011 Ma | |

|---|---|

| |

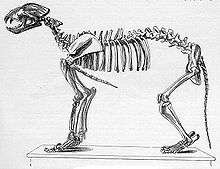

| Skeleton in Vienna | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Family: | Felidae |

| Genus: | Panthera |

| Species: | P. leo |

| Subspecies: | †P. l. spelaea |

| Trinomial name | |

| Panthera leo spelaea Goldfuss, 1810[1] | |

| |

| The maximal range of cave lions - red indicates Panthera spelaea, blue Panthera atrox, and green Panthera leo leo/Panthera leo persica. | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Panthera leo spelaea or P. spelaea, commonly known as the European or Eurasian cave lion, is an extinct subspecies of lion. It is known from fossils and many examples of prehistoric art.

Taxonomy

P. leo spelaea has been proposed as a separate species Panthera spelaea.[2] One authority considered the cave lion to be more closely related to the tiger based on a comparison of skull shapes, which would have resulted in the formal name Panthera tigris spelaea.[3] Past DNA studies indicated that among extant felids, the cave lion was most closely related to the modern lion,[4][5] and that it formed a single population with the Beringian cave lion,[5] which has sometimes been considered a distinct form. Therefore, the cave lion ranged from Europe to Alaska over the Bering land bridge until the late Pleistocene. A recent DNA study indicates that it is a separate species which diverged from a common ancestor shared with the lion 1.9 million years ago[6]

Analysis of skulls and mandibles of a lion that inhabited Yakutia (Russia), Alaska (United States), and the Yukon Territory (Canada) during the Pleistocene epoch suggested that it was a new subspecies different from the other prehistoric lions, Panthera leo vereshchagini, known as the East Siberian- or Beringian cave lion.[7] It differed from Panthera leo spelaea by its larger size and from the American lion (Panthera leo atrox) by its smaller size and by skull proportions.[7][8] However, recent genetic research, using ancient DNA from Beringian lions found no evidence for separating Panthera leo vereshchagini from the European cave lion; indeed, DNA signatures from lions from Europe and Alaska were indistinguishable, suggesting one large panmictic population.[5]

In October 2015 two frozen cave lion cubs, estimated to be at least 10,000 years old, were discovered in Yakutia, Siberia in permafrost.[9][10] Research on the specimens, named Uyan and Dina, indicated the cubs were likely barely a week old at the time of their deaths, as their baby teeth had not fully erupted. Further evidence shows the cubs were, like modern lions, hidden at a den site until they were old enough to join the pride. Researchers think that the cubs were trapped and killed by a landslide, and that without air, the cubs were preserved in such good condition. A second expedition to the site where the cubs were found is planned for 2016, in hopes of finding either the remains of a third cub or possibly the cubs' mother.[11]

Evolution

P. leo spelaea evolved from the earlier Panthera leo fossilis, which first appeared in Europe about 700,000 years ago. Genetic evidence indicates this lineage was isolated from extant lions after its dispersal to Europe.[4] P. l. spelaea lived from circa 370,000 to 10,000 years ago, during the Pleistocene epoch. Apparently, it became extinct about 12,400 14

C years ago,[5] as the Würm glaciation receded, by which time the cave lion spread from Europe to Beringia and the Far East.[5][12] However, it also appears from genetics that the extant Asiatic lion separated from its African cousin around 100,000 years ago. In other words, the anatomically modern lion spread from Africa to Eurasia, millennia before the cave lion's extinction there.[12][13][14]

Mitochondrial DNA sequence data from fossil remains show the American lion (P. l. atrox) represents a sister lineage to P. l. spelaea, and likely arose when an early P. l. spelaea population became isolated south of the North American continental ice sheet about 0.34 Mya.[5] The following cladogram shows the genetic relationship between P. spelaea and other pantherines according to Barnett et al. (2016),[15] besides Linnaeus (1758):[16][17]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Description

.jpg)

Considering it to be a lion, this subspecies was one of the largest lions. The skeleton of an adult male, which was found in 1985 near Siegsdorf (Germany), had a shoulder height of around 1.2 m (3.9 ft) and a head-body length of 2.1 m (6.9 ft) without the tail. This is similar to the size of a very large modern lion. A large specimen is estimated to weigh 317-362 kg (700-800 lb). The size of this male has been exceeded by other specimens of this subspecies. Therefore, this cat may have been over 10% bigger than modern lions and smaller than the earlier cave lion subspecies Panthera leo fossilis or the relatively larger American lion (Panthera leo atrox).[18]

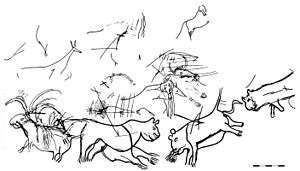

The cave lion is known from Paleolithic cave paintings, ivory carvings, and clay figurines. These representations indicate cave lions had rounded, protruding ears, tufted tails, possibly faint tiger-like stripes, and at least some had a "ruff" or primitive mane around their necks, possibly indicating males. Other archaeological artifacts indicate they were featured in Paleolithic religious rituals. In France's Chauvet cave, there is a drawing, which was estimated to be 30,000 years old, and depicts two cave lions walking together, with one in the foreground, and the other in the background. The lion in the foreground is smaller than the lion in the background, which has a scrotum, but no mane.[12]

In 2008, a well-preserved cave lion specimen was unearthed near the Maly Anyuy River in Chukotka, Russia, which still retained some clumps of hair.[19] A 2016 study identified the hair on the basis of DNA as being cave lion hair, and comparison to the hair of an African lion revealed that cave lion hair was similar in color to that of modern lions, though slightly lighter. In addition to slightly different coloration, cave lions had a very thick and dense undercoat comprising closed and compressed yellowish-to-white wavy downy hair with a smaller mass of darker coloured guard hairs, as an adaptation to the ice age climate.[20]

Palaeobiology

These active carnivores probably preyed upon the large herbivorous animals of their time, including horses, reindeer, bison and even injured, old or young mammoths,[21] which would have been killed by a powerful bite from their sharp teeth.[22] Some paintings of them in caves show several hunting together, which suggests the hunting strategy of contemporary lionesses. Isotopic analyses of bone collagen samples extracted from fossils suggest reindeer and cave bear cubs were prominent in the diets of northwestern European cave lions.[23][24] There was a suggestion of a shift in dietary preferences subsequent to the disappearance of the cave hyena.[24] The last cave lions seem to have focused on reindeer, up to the brink of local extinction, or extirpation of both species.[24]

Distribution and habitat

P. leo spelaea populations were widespread in parts of Europe, Asia, and northwestern North America, from Great Britain, Germany, and Spain[21] all the way across the Bering Strait to the Yukon Territory, and from Siberia to Turkistan.[25] Panthera youngi reached to the Japanese Archipelago.[26]

P. leo spelaea received its vernacular names because large quantities of its remains have been found in caves.[21] It had a wide habitat tolerance, but probably preferred conifer forests and grasslands,[27] where medium-sized to large herbivores occurred. Fossil footprints of lions, which were found together with those of reindeer, demonstrate the lions once occurred even in subpolar climates. The presence of fully articulated adult cave lion skeletons, deep in cave bear dens, indicates these lions may have occasionally entered dens to prey on hibernating cave bears, with some dying in the attempt.[28]

See also

Notes

References

- ↑ Goldfuss, G. A. (1810). Die Umgebungen von Muggensdorf. Ein Taschenbuch für Freunde der Natur und Alterumskunde. Erlangen: Palm, J. J.

- ↑ Christiansen, Per (2008). "Phylogeny of the great cats (Felidae: Pantherinae), and the influence of fossil taxa and missing characters". Cladistics. 24 (6): 977–992. doi:10.1111/j.1096-0031.2008.00226.x.

- ↑ Groiss, J. Th. (1996): "Der Höhlentiger Panthera tigris spelaea (Goldfuss)". Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie 7 : 399–414.

- 1 2 Burger, J.; Rosendahl, W.; Loreille, O.; Hemmer, H.; Eriksson, T.; Götherström, A.; Hiller, J.; Collins, M. J.; Wess, T.; Alt, K. W. (2004). "Molecular phylogeny of the extinct cave lion Panthera leo spelaea". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 30 (3): 841–849. PMID 15012963. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2003.07.020. Retrieved 2011-12-17.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Barnett, R.; et al. (2009). "Phylogeography of lions (Panthera leo ssp.) reveals three distinct taxa and a late Pleistocene reduction in genetic diversity" (PDF). Molecular Ecology. 18 (8): 1668–1677. PMID 19302360. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2009.04134.x. Retrieved 2011-11-23.

- ↑ Barnett, R.; Mendoza, M. L. Z.; Soares, A. E. R.; Ho, S. Y. W.; Zazula, G.; Yamaguchi, N.; Shapiro, B.; Kirillova, I. V.; Larson, G.; Gilbert, M. T. P. (2016-06-23). "Mitogenomics of the Extinct Cave Lion, Panthera spelaea (Goldfuss, 1810), Resolve its Position within the Panthera Cats". Open Quaternary. 2. doi:10.5334/oq.24.

- 1 2 Burger, Joachim; Rosendahl, Wilfried; Loreille, Odile; Hemmer, Helmut; Eriksson, Torsten; Götherström, Anders; Hiller, Jennifer; Collins, Matthew J.; Wess, Timothy; Alt, Kurt W.; et al. (March 2004). "Molecular phylogeny of the extinct cave lion Panthera leo spelaea" (PDF). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 30 (3): 841–849. PMID 15012963. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2003.07.020. Retrieved 2007-09-20.

- ↑ Baryshnikov, G.F.; Boeskorov, G. (2001). "The Pleistocene cave lion, Panthera spelaea (Carnivora, Felidae) from Yakutia, Russia". Cranium. 18: 7–24.

- ↑ "Meet this extinct cave lion, at least 10,000 years old - world exclusive". siberiantimes.com. Retrieved 2015-10-29.

- ↑ Switek, Brian (2015-10-28). "Frozen Cave Lion Cubs from the Ice Age Found in Siberia". National Geographic News. Retrieved 2015-10-29.

- ↑ "Whiskers still bristling after more than 12,000 years in the Siberian cold". The Siberian Times. 17 November 2015. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- 1 2 3 Yamaguchi, Nobuyuki; Cooper, Alan; Werdelin, Lars; MacDonald, David W. (August 2004). "Evolution of the mane and group-living in the lion (Panthera leo): a review". Journal of Zoology. 263 (4): 329–342. doi:10.1017/S0952836904005242.

- ↑ Nowell, K., Jackson, P. (1996). "Asiatic lion". Wild Cats: Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan (PDF). Gland, Switzerland: IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group. pp. 17–21. ISBN 2-8317-0045-0.

- ↑ Haas, S.K.; Hayssen, V.; Krausman, P.R. (2005). "Panthera leo" (PDF). Mammalian Species. 762: 1–11. doi:10.1644/1545-1410(2005)762[0001:PL]2.0.CO;2.

- ↑ Barnett, Ross; Mendoza, Marie Lisandra Zepeda; Soares, André Elias Rodrigues; Ho, Simon Y. W.; Zazula, Grant; Yamaguchi, Nobuyuki; Shapiro, Beth; Kirillova, Irina V.; Larson, Greger; Gilbert, M. Thomas P. (2016). "Mitogenomics of the Extinct Cave Lion, Panthera spelaea (Goldfuss, 1810), Resolve its Position within the Panthera Cats". Open Quaternary. 2. doi:10.5334/oq.24.

- ↑ Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M., eds. (2005). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ↑ Henschel, P.; Hunter, L.; Breitenmoser, U.; Purchase, N.; Packer, C.; Khorozyan, I.; Bauer, H.; Marker, L.; Sogbohossou, E.; Breitenmoser-Würsten, C. (2008). "Panthera pardus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2014.3. International Union for Conservation of Nature.

- ↑ W. v. Koenigswald: Lebendige Eiszeit. Theiss-Verlag, 2002. ISBN 3-8062-1734-3

- ↑ Kirillova, Irina (2015). "On the discovery of a cave lion from the Malyi Anyui River (Chukotka, Russia)". Quaternary Science Reviews. Volume 117: 135–151 – via Elsevier Science Direct.

- ↑ Chernova, O.F (2016). "Morphological and genetic identification and isotopic study of the hair of a cave lion (Panthera spelaea Goldfuss, 1810) from the Malyi Anyui River (Chukotka, Russia)". Quaternary Science Reviews. Volume 142: Pages 61–73 – via Elsevier Science Direct.

- 1 2 3 Arduini, P. & Teruzzi, G. 1993. The MacDonald encyclopedia of fossils. Little, Brown and Company, London. 320pp.

- ↑ Lessem, D. 1999. Dinosaurs to dodos. An encyclopedia of extinct animals. Scholastic, New York. 122pp.

- ↑ Curry, A. (2011-11-21). "Dissecting the Cave Lion Diet". Science Now. AAAS. Retrieved 2011-11-24.

- 1 2 3 Bocherens, H.; et al. (2011-12-06). "Isotopic evidence for dietary ecology of cave lion (Panthera spelaea) in North-Western Europe: Prey choice, competition and implications for extinction". Quaternary International. 245 (2): 249–261. Bibcode:2011QuInt.245..249B. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2011.02.023. Retrieved 2011-11-24.

- ↑ 'Supersize' lions roamed Britain BBC News 1 April 2009

- ↑ Ohdachi S.,Ishibashi Y., Iwasa A.M., Fukui D., Saitohet T. et al., 2015, The Wild Mammals of Japan, Shoukadoh, ISBN 978-4-87974-691-7

- ↑ Hublin, J.-J. 1984. The Hamlyn encyclopedia of prehistoric animals. Hamlyn, London. 318pp.

- ↑ "15TH INTERNATIONAL CAVE BEAR SYMPOSIUM SPIŠSKÁ NOVÁ VES, SLOVAKIA, 17th – 20th of September 2009" Archived 31 March 2010 at the Wayback Machine.

External links

| Wikispecies has information related to: Panthera leo spelaea |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Panthera leo spelaea. |

- Prehistoric cats and prehistoric cat-like creatures, from the Messybeast Cat Resource Archive.

- American lion, by C. R. Harrington, from Yukon Beringia Interpretative Center.

- The mammoth and the flood, volume 5, chapter 1, by Hans Krause.

- Hoyle and cavetigers, from the Dinosaur Mailing List. (Groiss)

- The Interaction of the European Cave Lion and Primitive Humans