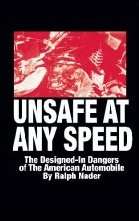

Unsafe at Any Speed

Exhibit featuring the book at Henry Ford Museum, Detroit | |

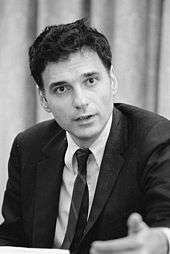

| Author | Ralph Nader |

|---|---|

| Publisher | Grossman Publishers |

Publication date | 30 November 1965[1] |

| OCLC | 568052 |

Unsafe at Any Speed: The Designed-In Dangers of the American Automobile by Ralph Nader, published in 1965, is a book accusing car manufacturers of resistance to the introduction of safety features such as seat belts, and their general reluctance to spend money on improving safety. It was a pioneering work containing substantial references and material from industry insiders. It was a best seller in non-fiction in 1966.

Theme

Unsafe at Any Speed is primarily known for its statements about the Corvair, though only one of the book's eight chapters covers the Corvair. It also deals with the use of tires and tire pressure being based on comfort rather than on safety, and the automobile industry disregarding technically based criticism.[2]

Organization and content

Each of the book's chapters covers a different aspect of automotive safety:

"The Sporty Corvair"

The subject for which the book is probably most widely known, the rear-engined Chevrolet Corvair, is covered in Chapter 1—"The Sporty Corvair-The One-Car Accident". This relates to the first (1960–1964) models that had a swing-axle suspension design which was prone to "tuck under" in certain circumstances. To make up for the cost-cutting lack of a front stabilizer bar (anti-roll bar), Corvairs required tire pressures which were outside of the tire manufacturers' recommended tolerances. The Corvair relied on an unusually high front to rear pressure differential (15psi front, 26psi rear, when cold; 18 psi and 30psi hot), and if one inflated the tires equally, as was standard practice for all other cars at the time, the result was a dangerous oversteer.[3] Despite the fact that proper tire pressures were more critical than for contemporaneous designs, this was not clearly stated to Chevrolet salespeople and Corvair owners. According to the standards laid down by the relevant industry body, the Tire and Rim Association, the pressures also rendered the front tires overloaded when there were two or more passengers on board.

An unadvertised at-cost option (#696) included upgraded springs and dampers, front anti-roll bars and rear-axle-rebound straps to prevent tuck-under. Aftermarket kits were also available, such as the EMPI Camber Compensator, for the knowledgeable owner. The suspension was modified for 1964 models, with inclusion of a standard front anti-roll bar and a transverse-mounted rear spring. In 1965, the totally redesigned four-link, fully independent rear suspension maintained a constant camber angle at the wheels. Corvairs from 1965 were not prone to the formerly characteristic tuck-under crashes.

George Caramagna, the Chevrolet suspension mechanic (who, Nader learned, had fought management over omission of the vital anti-sway bar that they were forced to install in later models) was vital to this issue. The missing bar had caused many crashes and it was Caramagna who precipitated the whole controversy by staying his ground on the issue.

"Disaster deferred"

Chapter 2 levels criticism on auto design elements such as instrument panels and dashboards that were often brightly finished with chrome and glossy enamels which could reflect sunlight or the headlights of oncoming motor vehicles into the driver's eyes. This problem, according to Nader, was well known by persons in the industry, but little was done to correct it.

Apart from some of the examples given in the Corvair chapter, Nader offers much about the gear shift quadrants on earlier cars fitted with automatic transmissions. Several examples are given of persons accidentally being run over, or cars that turned into runaways because the driver operating the vehicle at the time of the accident was not familiar with its shift pattern and would shift into reverse when intending to shift to park. Nader makes an appeal to the auto industry to standardize gearshift patterns between makes and models as a safety issue.

Early automatic transmissions, including GM's Hydra-Matic, Packard's Ultramatic, and Borg Warner's automatic used by a number of independent manufacturers (Rambler, Studebaker) used a pattern of "P N D L R", which put Reverse at the bottom of the quadrant, next to Low which was contrary to the pattern used by other manufacturers. Drivers used to moving the shift lever all the way down for "low gear" would accidentally select "R" and would unexpectedly move the car backwards. In addition, other manufacturers, such as Chrysler, used a push-button selector to choose gear ranges. Ford was the first to use the "P R N D L" pattern, which separated Reverse from forward ranges by Neutral. Eventually this pattern became the standard for all automatic-shift cars.

Chevrolet's Powerglide, at least as seen on the Corvair, used a "R N D L" pattern, which separated the Reverse from the Drive gears by neutral in the ideal way, but which had no "P" selection, relying instead on the process used with a manual transmission of the driver selecting N (neutral) and using a separate parking brake when parking.

Chapter 2 also exposes problems in workmanship and the failure of companies to honor warranties.

"The second collision"

Chapter 3 documents the history of crash science focusing on the effect on the human body (the second collision) as it collides with the interior of the car as the car hits another object (the first collision). Nader says that much knowledge was available to designers by the early 1960s but it was largely ignored within the American automotive industry. There are in-depth discussions about the steering assembly, instrument panel, windshield, passenger restraint, and the passenger compartment (which included everything from door strength to roll-over bars). Due to this, the "Nader bolt" was installed to reinforce the door and suicide doors were discontinued because of a lack of door strength.

"The power to pollute"

Chapter 4 documents the automobile's impact on air pollution and its contribution to smog, with a particular focus on Los Angeles.

"The engineers"

Chapter 5 is about Detroit automotive engineers' general unwillingness to focus on road-safety improvements for fear of alienating the buyer or making cars too expensive. Nader counters by pointing out that, at the time, annual (and unnecessary) styling changes added, on average, about $700 to the consumer cost of a new car. This compared to an average expenditure in safety by the automotive companies of about twenty-three cents per car.[4]:p187

"The stylists"

Chapter 6 explores the excessive ornamentation that appeared on cars, particularly in the late 1950s, and the dominance of car design over good engineering. Of the 1950s designs, Nader notes "bumpers shaped like sled-runners and sloping grille work above the bumpers, which give the effect of 'leaning into the wind', increase ... the car's potential for exerting down-and-under pressures on the pedestrian."[4]:p227 See current practice at Pedestrian safety through vehicle design.

"The traffic safety establishment"

Subtitled "Damn the driver and spare the car," Chapter 7 discusses the way the blame for accidents and fatalities was placed on the driver. The book says that the road safety mantra called the "Three E's" ("Engineering, Enforcement and Education") was created by the industry in the 1920s to distract attention from the real problems of vehicle safety, such as the fact that some were sold with tires that could not bear the weight of a fully loaded vehicle. To the industry, he said "Enforcement" and "Education" meant the driver, while "Engineering" was all about the road. As late as 1965, he noted, 320 million federal dollars were allocated to highway beautification, while just $500,000 was dedicated to highway safety.[4]:p294

"The coming struggle for safety"

Chapter 8, the concluding chapter, suggests that the automotive industry should be forced by government to pay greater attention to safety in the face of mounting evidence about preventable death and injury.

Reception

Unsafe at Any Speed was a best seller in nonfiction by Spring 1966[1][5] and helped spur the passage of the National Traffic and Motor Vehicle Safety Act in 1966, the country’s first significant automobile safety legislation.[6] It also prompted the passage of seat-belt laws in 49 states (all but New Hampshire) and a number of other road-safety initiatives.[7]

Government response

The book has continuing relevance: it addressed what Nader perceived as the political meddling of the car industry to oppose new safety features, which parallels the debates in the 1990s over the mandatory fitting of air bags in the United States, and industry efforts by the ACEA to delay the introduction of crash tests to assess vehicle-front pedestrian protection in the European Union.[8]

Industry response

Nader says that GM responded to his criticism of the Corvair by trying to destroy Nader's image and to silence him. It "(1) conducted a series of interviews with acquaintances of the plaintiff, 'questioning them about, and casting aspersions upon [his] political, social, racial and religious views; his integrity; his sexual proclivities and inclinations; and his personal habits'; (2) kept him under surveillance in public places for an unreasonable length of time; (3) caused him to be accosted by girls for the purpose of entrapping him into illicit relationships; (4) made threatening, harassing and obnoxious telephone calls to him; (5) tapped his telephone and eavesdropped, by means of mechanical and electronic equipment, on his private conversations with others; and (6) conducted a 'continuing' and harassing investigation of him."[9]

On March 22, 1966, GM President James Roche was forced to appear before a United States Senate subcommittee, and to apologize to Nader for the company's campaign of harassment and intimidation. Nader later successfully sued GM for excessive invasion of privacy.[9] It was the money from this case that allowed him to lobby for consumer rights, leading to the creation of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and the Clean Air Act, among other things.[10]

Former GM executive John DeLorean asserted in On a Clear Day You Can See General Motors (1979) that Nader's criticisms were valid.[11] Former Ford and Chrysler President Lee Iacocca said the Corvair was 'unsafe' and a 'terrible' car in his book, Iacocca: An Autobiography.[12]

Criticisms of the book

The U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT) issued a press release dated August 12, 1972, setting out the findings of 1971 NHTSA testing—after the Corvair had been out of production for more than three years. The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) had conducted a series of comparative tests in 1971 studying the handling of the 1963 Corvair and four contemporary cars, a Ford Falcon, Plymouth Valiant, Volkswagen Beetle, Renault Dauphine—along with a second generation Corvair with revised suspension design. The subsequent 143-claimpage report (PB 211-015, available from NTIS) reviewed a series of actual handling tests designed to evaluate the handling and stability under extreme conditions; a review of national accident data compiled by insurance companies and traffic authorities for the cars in the test—and a review of related General Motors/Chevrolet internal letters, memos, tests, reports, etc. regarding the Corvair's handling.[13] NHTSA went on to contract a three-person advisory panel of independent professional engineers to review the scope and competency of their tests. This review panel then issued its own 24-page report (PB 211-014, available from NTIS), which concluded that "the 1960-63 Corvair compares favorably with contemporary vehicles used in the tests...the handling and stability performance of the 1960-63 Corvair does not result in an abnormal potential for loss of control or rollover, and it is at least as good as the performance of some contemporary vehicles both foreign and domestic."

Economist Thomas Sowell said in The Vision of the Anointed (1995) that Nader was dismissive of the trade-off between safety and affordability. According to Sowell, Nader also did not note that motor vehicle death rates per 100 million passenger miles fell over the years from 17.9 in 1925 to 5.5 in 1965.[14]

Journalist David E. Davis, in a 2009 article in Automobile Magazine, criticized Nader for purportedly focusing on the Corvair while ignoring other contemporary vehicles with swing-axle rear suspensions, including cars from Porsche, Mercedes-Benz and Volkswagen, notwithstanding the fact that Nader's Center for Auto Safety had published a book critical of the Beetle.[15]

Journalist Timothy Noah said the (Corvair) was not significantly more dangerous than a number of American cars of its time, citing government and independent reports: "... the car was not, in fact, appreciably less safe than a number of other cars on the market."[16]

In 2005, the book received an honorable mention by conservative publication Human Events for its "Most Harmful Books of the 19th and 20th Centuries", meaning two or more out of fifteen conservative thinkers voted for it. Winners included authors Betty Friedan and John Maynard Keynes.[17]

References

- 1 2 "Unsafe at Any Speed hits bookstores". A&E Television Networks, LLC. Retrieved 16 May 2013.

- ↑ Nader R. "Unsafe at any speed: the designed-in dangers of the American automobile. 1965". Am J Public Health. 101: 254–6. PMC 3020193

. PMID 21228290.

. PMID 21228290. - ↑ CSERE, CSABA. "General Motors Celebrates a 100-Year History of Technological Breakthroughs". Car and Driver. Retrieved 20 March 2013.

- 1 2 3 Unsafe at Any Speed Grossman Publishers, New York (1965)

- ↑ Jensen, Christopher (November 26, 2015). "50 Years Ago, ‘Unsafe at Any Speed’ Shook the Auto World". The New York Times. Retrieved April 27, 2016.

By the spring of 1966, “Unsafe at Any Speed” was a best seller for nonfiction

- ↑ "Unsafe at Any Speed hits bookstores". History (U.S. TV channel). A & E. Retrieved April 27, 2016.

On this day in 1965, 32-year-old lawyer Ralph Nader publishes the muckraking book Unsafe at Any Speed: The Designed-In Dangers of the American Automobile. The book became a best-seller right away.

- ↑ Wyden, Peter (1987). The Unknown Iacocca. William Morrow and Company. ISBN 068806616X.

Nader, another poor boy, rose to national hero status on the critic's side of America's car wars.

- ↑ Milton Bertin-Jones. "An Integrated, Market-based approach to vehicle safety in road transport". SAE Technical Paper Nº 2003-01-0104.

- 1 2 Nader v. General Motors Corp. Court of Appeals of New York, 1970

- ↑ An Unreasonable Man, 2006 documentary film

- ↑ Wright, Parick J. (1979). On a Clear Day You Can See General Motors. Grosse Point, MI: Wright Enterprises. pp. 6, 51, 64.

- ↑ Iacocca, Lee (1984). Iacocca: An Autobiography. Toronto: Bantam Books. p. 161. ISBN 0-553-05067-2.

- ↑ "PB 211-015: Evaluation of the 1960-1963 Corvair Handling and Stability". National Technical Information Service. July 1972.

- ↑ Thomas Sowell: Vision of the Anointed. Basic Books, 1995, pp 70 et seq.

- ↑ David E. Davis, Jr. "American Driver: The Late Ralph Nader". Automobile Magazine, April 2009.

- ↑ Nader and the Corvair, The New Republic - October 4, 2011

- ↑ "Ten Most Harmful Books of the 19th and 20th Centuries". Human Events. Retrieved 21 December 2012.

Further reading

- Unsafe at Any Speed The Designed-In Dangers of The American Automobile (1965) Grossman Publishers, New York LCCN 65--16856

- Interview With Dr. Jorg Beckmann of the ETSC. "Safety experts and the motor car lobby meet head on in Brussels." TEC, Traffic Engineering and Control, Vol 44 N°7 July/August 2003 Hemming Group ISSN 0041-0683