Territories of the United States

Territories of the United States | |

|---|---|

| |

The 50 states and the Federal District Commonwealth (see footnote) Incorporated unorganized territory Unincorporated organized territory Unincorporated unorganized territory | |

| Largest settlement | San Juan, Puerto Rico, United States |

| Languages | English, Spanish, Hawaiian, Chamorro, Carolinian, Samoan |

| Demonym | American |

| Territories | |

| Leaders | |

| Donald Trump | |

| List of current territorial governors | |

| Area | |

• Total | 22,294.19 km2 (8,607.83 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• Estimate | 4,065,516 |

| Currency | United States Dollar |

| Date format | mm/dd/yyyy (AD) |

| |

| Administrative divisions of the United States |

|---|

| First level |

|

|

| Second level |

|

| Third level |

|

|

| Fourth level |

| Other areas |

|

|

.jpg)

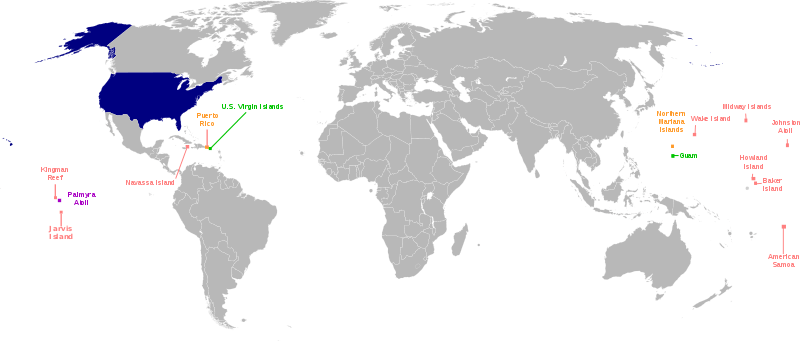

Territories of the United States are sub-national administrative divisions directly overseen by the United States federal government (unlike U.S. states, which share sovereignty with the federal government). These territories are classified by whether they are incorporated (part of the United States proper) and whether they have an organized government through an Organic Act passed by the U.S. Congress.[2]

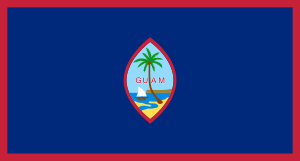

The United States currently has sixteen territories. Five of them are permanently inhabited and are classified as unincorporated territories: Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands in the Caribbean; Guam and the Northern Mariana Islands in the Marianas archipelago in the western North Pacific Ocean; and American Samoa in the South Pacific. They are organized, self-governing territories with locally elected governors and territorial legislatures. Each also elects a non-voting member (or resident commissioner) to the U.S. House of Representatives.[3][4] The eleven other territories are small islands, atolls and reefs, also spread across the Caribbean and Pacific, with no native or permanent populations. These are Palmyra Atoll, Baker Island, Howland Island, Jarvis Island, Johnston Atoll, Kingman Reef, Midway Islands, Bajo Nuevo Bank, Navassa Island, Serranilla Bank and Wake Island, which are claimed by the United States under the Guano Islands Act of 1856. The status of some is disputed by Colombia, Haiti, Honduras, Jamaica, Nicaragua, and the Marshall Islands. The Palmyra Atoll is the only territory currently incorporated.

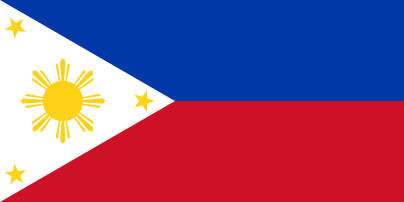

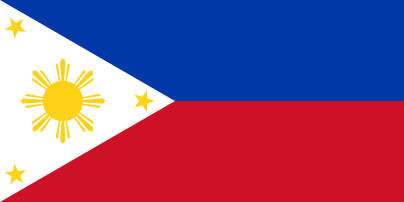

Historically, territories were created to govern newly acquired land while the borders of the United States were still evolving. Most territories eventually attained statehood. Other territories administered by the United States went on to become independent countries, such as the Philippines, Micronesia, Marshall Islands and Palau. Micronesia, Marshall Islands and Palau gained independence under the Compact of Free Association (COFA), which allows the U.S. full authority over aid and defense in exchange for continued access to U.S. health care, government services such as the FCC and United States Postal Service, and the right for COFA citizens to work freely in the United States and vice versa.

Many organized incorporated territories of the United States existed from 1789 to 1959 (the first being the Northwest and the Southwest territories, the last being the Alaska Territory and the Hawaii Territory), through which 31 territories applied for and were granted statehood. In the process of organizing and promoting territories to statehood, some areas of a territory demographically lacking sufficient development and population densities were temporarily orphaned from parts of a larger territory at the time a vote was taken petitioning Congress for statehood rights. For example, when a portion of the Missouri Territory became the state of Missouri, the remaining portion of the territory, consisting of the present states of Iowa, Nebraska and the Dakotas, most of Kansas, Wyoming, and Montana, and parts of Colorado and Minnesota, effectively became an unorganized territory.

Current territories

Currently, the United States has 16 territories, five of which are permanently inhabited: Puerto Rico, Guam, Northern Mariana Islands, United States Virgin Islands and American Samoa. The 11 uninhabited territories administered by the Interior Department are Palmyra Atoll, Baker Island, Howland Island, Jarvis Island, Johnston Atoll, Kingman Reef, and Midway Islands. While claimed by the US, Navassa Island, Wake Island, Serranilla Bank and Bajo Nuevo Bank are disputed.[5][6]

Territories have always been a part of the United States.[7] By Act of Congress, the term "United States", when used in a geographical sense, means "the continental United States, Alaska, Hawaii, Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Virgin Islands of the United States".[8] Since political union with the Northern Mariana Islands in 1986, they too are treated as a part of the U.S.[8] An Executive Order in 2007 includes American Samoa as U.S. "geographical extent" duly reflected in U.S. State Department documents.[9]

Inhabited United States territories have democratic self-government, in local three-branch governments, found respectively in Pago Pago, American Samoa; Hagåtña, Territory of Guam; Saipan, Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands; San Juan, Commonwealth of Puerto Rico; Charlotte Amalie, United States Virgin Islands.[10]

Approximately 4 million islanders are U.S. citizens; about 32,000 U.S. non-citizen nationals live in American Samoa.[11] Under current law among the territories, "only persons born in American Samoa and Swains Island are non-citizen U.S. nationals."[12] American Samoans are under the protection of the U.S., with freedom of U.S. travel without visas.[12]

The five inhabited U.S. territories have local voting rights and protections under U.S. courts, pay some U.S. taxes, and have limited representation in the U.S. House of Representatives. They popularly elect "Members of Congress" who, like the delegate from Washington, D.C., "possess the same powers as other members of the House, except that they may not vote when the House is meeting as the House of Representatives."[13] They participate in debate, are assigned offices and money for staff, and appoint constituents from their territories to the Military (viz., Army), Naval (viz., Navy and Marine Corps), Air Force, and Merchant Marine service academies.[13] They can vote in committee on all legislation presented to the House of Representatives, they are included in their party count for each committee, and they are equal to senators on conference committees. Depending on the congress, they may also vote on the floor in the House Committee of the Whole.[14]

Members of Congress from the territories seated as of January 2017 are Gregorio Sablan for the Northern Mariana Islands, Madeleine Bordallo for Guam, Amata Coleman Radewagen for American Samoa, Jenniffer González for Puerto Rico, and Stacey Plaskett for the U.S. Virgin Islands.[15]

Every four years, the Democratic and Republican political parties nominate their presidential candidates at conventions which include delegates from the five major territories.[16] The citizens there, however, do not vote in the general election for U.S. President.

Incorporated and unincorporated territories

An incorporated territory of the United States is a specific area under the jurisdiction of the United States, over which the United States Congress has determined that the United States Constitution is to be applied to the territory's local government and inhabitants in its entirety (e.g., citizenship, trial by jury), in the same manner as it applies to the local governments and residents of the U.S. states. Incorporated territories are considered an integral part of the United States, as opposed to being merely possessions.[17]

From 1901 to 1905, the U.S. Supreme Court in a series of opinions known as the Insular Cases held that the Constitution extended ex proprio vigore (by its own force) to the territories. However, the Court in these cases also established the doctrine of territorial incorporation, under which the Constitution applies fully only in incorporated territories such as the then Territory of Alaska and Territory of Hawaii, and applies only partially in the new unincorporated territories of Puerto Rico, Guam and the Philippines.[18][19]

The U.S. had no unincorporated territories (also called "overseas possessions" or "insular areas") until 1856. In that year the U.S. Congress enacted the Guano Islands Act, which authorised the President to take possession of unclaimed islands for the purpose of mining guano. By virtue of this law, over the years the U.S. took control and claimed rights in respect of many islands, atolls etc., especially in the Caribbean and the Pacific, most of which have since been abandoned. The U.S. has also acquired territories under other circumstances, such as under the Treaty of Paris that ended the Spanish–American War. The constitutional position of these unincorporated territories was considered by the Supreme Court in Balzac v. People of Porto Rico, 258 U.S. 298, 312 (1922), where the Court used, as an argument of non-incorporated territory, the following statement regarding the U.S. court in Puerto Rico:

The United States District Court is not a true United States court established under article 3 of the Constitution to administer the judicial power of the United States therein conveyed. It is created by virtue of the sovereign congressional faculty, granted under article 4, 3, of that instrument, of making all needful rules and regulations respecting the territory belonging to the United States. The resemblance of its jurisdiction to that of true United States courts, in offering an opportunity to nonresidents of resorting to a tribunal not subject to local influence, does not change its character as a mere territorial court.[20]

In Glidden Co. v. Zdanok, 370 U.S. 530 (1962) the court cited Balzac and made the following statement regarding courts in unincorporated territories:

Upon like considerations, Article III has been viewed as inapplicable to courts created in unincorporated territories outside the mainland, Downes v. Bidwell, 182 U.S. 244, 266 -267; Balzac v. Porto Rico, 258 U.S. 298, 312 -313; cf. Dorr v. United States, 195 U.S. 138, 145, 149, and to the consular courts established by concessions from foreign countries, In re Ross, 140 U.S. 453, 464 -465, 480. 18

The U.S. Supreme Court offers two ways in which incorporation could be made: "incorporation is not to be assumed without express declaration, or an implication so strong as to exclude any other view."

Express or implied?

In Balzac,[21] where Chief Justice Taft delivered the opinion of the Court, the meaning of implied was specified:

Had Congress intended to take the important step of changing the treaty status of Puerto Rico by incorporating it into the Union, it is reasonable to suppose that it would have done so by the plain declaration, and would not have left it to mere inference. Before the question became acute at the close of the Spanish War, the distinction between acquisition and incorporation was not regarded as important, or at least it was not fully understood and had not aroused great controversy. Before that, the purpose of Congress might well be a matter of mere inference from various legislative acts; but in these latter days, incorporation is not to be assumed without express declaration, or an implication so strong as to exclude any other view.

Incorporated territories U.S. Supreme Court declarations

In Rassmussen v. U S, 197 U.S. 516 (1905), quoting from Article III of the 1867 treaty for the purchase of Alaska,[22] the Supreme Court said, "'The inhabitants of the ceded territory ... shall be admitted to the enjoyment of all the rights, advantages, and immunities of citizens of the United States; ...'. This declaration, although somewhat changed in phraseology, is the equivalent, as pointed out in Downes v. Bidwell, of the formula, employed from the beginning to express the purpose to incorporate acquired territory into the United States, especially in the absence of other provisions showing an intention to the contrary."[23] Here we see that the act of incorporation is on the people of the territory, not on the territory per se, by extending the privileges and immunities clause of the Constitution to them. The U.S. Supreme Court statements follow:

Alaska Territory

Congress express declaration:

Rassmussen v. the United States (197 U.S. 516, 522 (1905)) arose out of a misdemeanor conviction in Alaska by a jury composed of six persons pursuant to a federal statute allowing such a procedure in Alaska. In a decision written by Justice White, a majority of the Court concluded that Alaska had been incorporated into the United States because the treaty of cession with Russia specifically declared that "the inhabitants of the ceded territory shall be admitted to the enjoyment of all the rights, advantages and immunities of citizens of the United States.[24]

In addition, there was Congressional implication so strong as to exclude any other view:

That Congress, shortly following the adoption of the treaty with Russia, clearly contemplated the incorporation of Alaska into the United States as a part thereof, we think plainly results from the act of July 20, 1868, concerning internal revenue taxation, chap. 186, 107 (15 Stat. at L. 167, U. S. Comp. Stat. 1901, p. 2277), and the act of July 27, 1868, chap. 273, extending the laws of the United States relating to customs, commerce, and navigation over Alaska, and establishing a collection district therein. 15 Stat. at L. 240. And this is fortified by subsequent action of Congress, which it is unnecessary to refer to.— Rassmussen at 533–534

Justice Brown, in his concurring opinion, also expressed the same thought:

Apparently, acceptance of the territory is insufficient in the opinion of the court in this case, since the result that Alaska is incorporated into the United States is reached, not through the treaty with Russia, or through the establishment of a civil government there, but from the act of July 20, 1868, concerning internal revenue taxation, and the act of July 27, 1868, extending the laws of the United States relating to the customs, commerce, and navigation over Alaska, and establishing a collection district there. Certain other acts are cited, notably the judiciary act of March 3, 1891, making it the duty of this court to assign [197 U.S. 516, 534] the several territories of the United States to particular Circuits.

Florida Territory

In Dorr v. USA (195 U.S. 138, 141–142 (1904)) Justice Marshall is quoted more extensively as follows:

The 6th article of the treaty of cession contains the following provision:The inhabitants of the territories which His Catholic Majesty cedes the United States by this treaty shall be incorporated in the Union of the United States as soon as may be consistent with the principles of the Federal Constitution, and admitted to the enjoyment of the privileges, rights, and immunities of the citizens of the United States. [8 Stat. at L. 256.] [195 U.S. 138, 142] 'This treaty is the law of the land, and admits the inhabitants of Florida to the enjoyment of the privileges, rights, and immunities of the citizens of the United States. It is unnecessary to inquire whether this is not their condition, independent of stipulation. They do not, however, participate in political power; they do not share in the government till Florida shall become a state. In the meantime Florida continues to be a territory of the United States, governed by virtue of that clause in the Constitution which empowers Congress 'to make all needful rules and regulations respecting the territory or other property belonging to the United States." [25]

In Downes v. Bidwell, 182 U.S. 244, 256 (1901), Justice Brown says:[26]

The same construction was adhered to in the treaty with Spain for the purchase of Florida (8 Stat. at L. 252) the 6th article of which provided that the inhabitants should 'be incorporated into the Union of the United States, as soon as may be consistent with the principles of the Federal Constitution;

Southwest Territory

In Downes v. Bidwell supra at 321–322, the first mention of incorporation is made in the following paragraph by Justice Brown:[26]

In view of this it cannot, it seems to me, be doubted that the United States continued to be composed of states and territories, all forming an integral part thereof and incorporated therein, as was the case prior to the adoption of the Constitution. Subsequently, the territory now embraced in the state of Tennessee was ceded to the United States by the state of North Carolina. In order to insure the rights of the native inhabitants, it was expressly stipulated that the inhabitants of the ceded territory should enjoy all the rights, privileges, benefits, and advantages set forth in the ordinance 'of the late Congress for the government of the western territory of the United States.

Louisiana Territory

In Downes v. Bidwell supra at 252, it was said:[26]

Owing to a new war between England and France being upon the point of breaking out, there was need for haste in the negotiations, and Mr. Livingston took the responsibility of disobeying his (Mr. Jefferson's) instructions, and, probably owing to the insistence of Bonaparte, consented to the 3d article of the treaty (with France to acquire the territory of Louisiana), which provided that 'the inhabitants of the ceded territory shall be incorporated in the Union of the United States, and admitted as soon as possible, according to the principles of the Federal Constitution, to the enjoyment of all the rights, advantages, and immunities of citizens of the United States; and in the meantime they shall be maintained and protected in the free enjoyment of their liberty, property, and the religion which they profess.' [8 Stat. at L. 202.] This evidently committed the government to the ultimate, but not to the immediate, admission of Louisiana as a state, ...

The Supreme Court of the United States is unanimous in its interpretation that the extension of the privileges and immunities clause of the Constitution of the United States to the inhabitants of a territory in effect produces the incorporation of that territory. The net effect of incorporation is that the territory becomes an integral part of the geographical boundaries of the United States and cannot, from then on, be separated. Indeed, the whole body of the U.S. Constitution is extended to the inhabitants of that territory, except for those provisions that relate to its federal character.

More so, the needful rules and regulations of the territorial clause must yield to the Constitution and the inherent constraints imposed on it in dealing with the privileges and immunities of the inhabitants of the incorporated territory. Notice must be taken that incorporation of a territory takes place through the incorporation of its inhabitants, not of the territory per se. As such, those inhabitants receive the full impact of the U.S. Constitution, except for those provisions that deal specifically with the federal character of the Union.

In the contemporary sense, the term "unincorporated territory" refers primarily to insular areas. There is currently only one incorporated territory, Palmyra Atoll, which is not an organized territory. Conversely, a territory can be organized without being an incorporated territory, a contemporary example being Puerto Rico.

See organized incorporated territories of the United States and unincorporated territories of the United States for timelines.

Organized territory

Lands under the sovereignty of the federal government (but not part of any state) that were given a measure of self-rule by the Congress through an Organic Act subject to the Congress' plenary powers under the territorial clause of Article IV, sec. 3, of the U.S. Constitution.[27]

Classification of current U.S. territories

Incorporated organized territories

No incorporated organized territories have existed since 1959, the last two being the Territory of Alaska and Territory of Hawaii, both of which achieved statehood in that year, with their representative stars being added in the blue field/canton of the American flag on Independence Day, July 4, in 1959 and 1960, respectively.

Incorporated unorganized territories

Many incorporated unorganized territories became incorporated organized territories or states. For example, when the eastern part of the incorporated organized territory called Minnesota became the state of Minnesota in 1858, the western part became part of an unorganized territory. Later that became a part of the Dakota Territory, out of which two states and some parts of other states were created. California was part of an unorganized territory when it became a state.

| Name | Location | Area | Population | Capital | Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

Polynesia & North Pacific | 12 km2 (5 sq mi) | 20 | As of 2007, partly privately owned by The Nature Conservancy with much of the rest owned by the federal government and managed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.[28][29] It is an archipelago of about 50 small islands with about 1.56 sq mi (4 km2) of land area, lying about 1,000 miles (1,600 km) south of Oahu, Hawaii. The atoll was acquired by the United States through the annexation of the Republic of Hawaii in 1898. When the Territory of Hawaii was incorporated on April 30, 1900, Palmyra Atoll was incorporated as part of that territory. However, when the State of Hawaii was admitted to the Union in 1959, the Act of Congress explicitly separated Palmyra Atoll from the newly federated state. Palmyra remained an incorporated territory, but received no new organized government.[30] |

There are also "territories" that have the status of being incorporated but that are not organized:

- U.S. coastal waters out to 12 nautical miles (22.2 km) offshore (except state waters extend a minimum of 3 nautical miles (5.6 km) offshore)

Unincorporated organized territories

| Name | Location | Area | Population | Capital | Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

Micronesia & North Pacific | 543 km2 (210 sq mi) | 159,358 | Hagåtña | Territory since 1898, Guam is the home of Naval Base Guam and Andersen Air Force Base. |

| |

Micronesia & North Pacific | 463.63 km2 (179 sq mi) | 77,000 | Saipan | Commonwealth since 1978; formerly a United Nations Trust Territory under the administration of the U.S. |

| |

Caribbean & North Atlantic | 9,104 km2 (3,515 sq mi) | 3,667,084 | San Juan | Unincorporated territory since 1898, a commonwealth since 1952. In November 2008, a U.S. District Court judge ruled that a sequence of Congressional actions have had the cumulative effect of changing Puerto Rico's status from "unincorporated" to "incorporated."[31] However, the issue has not finished making its way through the court system;[32] and the U.S. government still refers to Puerto Rico as unincorporated.[33] See the Puerto Rico section in the article, Organized incorporated territories of the United States, and also the article, Political status of Puerto Rico. |

| |

Caribbean & North Atlantic | 346.36 km2 (134 sq mi) | 106,405 | Charlotte Amalie | Purchased by the U.S. from Denmark in 1917. |

Unincorporated unorganized territories

| Name | Location | Area | Population | Capital | Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

Polynesia & South Pacific | 197.1 km2 (76 sq mi) | 55,519 | Pago Pago | Territory since 1898. Locally self-governing under a constitution last revised in 1967.[34] |

| Baker Island[lower-alpha 1] | North Pacific | 2.1 km2 (1 sq mi) | 0 | Claimed under the Guano Islands Act on October 28, 1856.[36][37] Formally annexed on May 13, 1936, and placed under the jurisdiction of the United States Department of the Interior.[38] | |

| |

North Pacific | 1,112.0 acres (450 ha) | 0 | Claimed under the Guano Islands Act on December 3, 1858.[36][37] Formally annexed on May 13, 1936, and placed under the jurisdiction of the United States Department of the Interior.[38] | |

| Jarvis Island[lower-alpha 1] | Polynesia & South Pacific | 4.5 km2 (2 sq mi) | 0 | Claimed under the Guano Islands Act on October 28, 1856.[36][37] Formally annexed on May 13, 1936, and placed under the jurisdiction of the United States Department of the Interior.[38] | |

| |

North Pacific | 4.5 km2 (2 sq mi) | 40 | Last used by the Department of Defense in 2004 | |

| Kingman Reef[lower-alpha 1] | Polynesia & North Pacific | 18 km2 (7 sq mi) | 0 | Claimed under the Guano Islands Act on February 8, 1860.[36][37] Formally annexed on May 10, 1922, and placed under the jurisdiction of the United States Department of the Navy on December 29, 1934.[39] | |

| |

Micronesia & North Pacific | 7.4 km2 (3 sq mi) | 188 | Territory since 1898; host to the Wake Island Airfield administered by U.S. Air Force; claimed by the Marshall Islands.[40] | |

| |

North Pacific | 6.2 km2 (2 sq mi) | 4 | Territory since 1859; primarily a wildlife refuge inhabited only by civilian contractors; previously under the jurisdiction of the Department of the Navy. | |

| |

Caribbean & North Atlantic | 5.4 km2 (2 sq mi) | 0 | Territory since 1857. Claimed by Haiti. | |

| Serranilla Bank | Caribbean & North Atlantic | 350 km2 (135 sq mi) | 0 | Administered by Colombia; site of a naval garrison. Claimed by the United States (since 1879 under the Guano Islands Act), Honduras, and Jamaica. A claim by Nicaragua was resolved in 2012 in favor of Colombia by the International Court of Justice, although the U.S. was not a party to that case and does not recognize the jurisdiction of the ICJ.[41] | |

| Bajo Nuevo Bank | Caribbean & North Atlantic | 110 km2 (42 sq mi) | 0 | Administered by Colombia. Claimed by the United States (under the Guano Islands Act), Jamaica. A claim by Nicaragua was resolved in 2012 in favor of Colombia by the International Court of Justice, although the U.S. was not a party to that case and does not recognize the jurisdiction of the ICJ.[41] |

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 These six territories, together with Palmyra Atoll, comprise the Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument.

Extraterritorial jurisdiction

The United States exercises some degree of extraterritorial jurisdiction in overseas areas such as:

- Guantanamo Bay Naval Base (since 1903): A 45 sq mi (117 km2) area of land along Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, to which the United States claims to hold a perpetual lease;[42] the Cuban government does not recognize America's claim, and has refused to accept any payment since 1959. The actual lease amount is just US$2,000 in gold per year (equivalent in value in 2004 to approximately US$4,000).[43]

- American Research stations in Antarctica: Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station, McMurdo Station, Palmer Station are under American jurisdiction, but held without sovereignty as per the Antarctic Treaty.

- Certain other parcels in foreign countries held by lease, such as military bases, depending on the terms of a lease, treaty, or status of forces agreement with the host country.

Associated states

The United States exercises a high degree of control in defense, funding, and government services in:

Federated States of Micronesia (since 1986)

Federated States of Micronesia (since 1986) Marshall Islands (since 1986)

Marshall Islands (since 1986) Palau (since 1994)

Palau (since 1994)

Classification of former U.S. territories and administered areas

Former incorporated organized territories of the United States

See Organized incorporated territories of the United States for a complete list.

Former unincorporated territories of the United States (incomplete)

- The Corn Islands (1914–1971): leased for 99 years under the Bryan-Chamorro Treaty. However, returned to Nicaragua upon the abrogation of the treaty in 1970.

- The Line Islands (?–1979): disputed claim with the United Kingdom. U.S. claim to most of the islands was ceded to Kiribati upon its independence in 1979. The U.S. retained Kingman Reef, Palmyra Atoll, and Jarvis Island.

-

Panama Canal Zone (1903–1979): sovereignty returned to Panama under the Torrijos-Carter Treaties of 1978. U.S. retained a military base there and control of the canal until December 31, 1999.

Panama Canal Zone (1903–1979): sovereignty returned to Panama under the Torrijos-Carter Treaties of 1978. U.S. retained a military base there and control of the canal until December 31, 1999. - The Philippine Islands (1898–1935), the Commonwealth of the Philippines (1935–46): granted full independence on July 4, 1946.

- Phoenix Islands (?–1979): disputed claim with the United Kingdom. U.S. claim ceded to Kiribati upon its independence in 1979. Baker Island and Howland Island, which could be considered part of this group, are retained by the U.S.

- Quita Sueño Bank (1869–1981): claimed under Guano Islands Act. Claim abandoned on September 7, 1981, by treaty.

- Roncador Bank (1856–1981): claimed under Guano Islands Act. Ceded to Colombia on September 7, 1981, by treaty.

- Serrana Bank (1874?–1981): claimed under Guano Islands Act. Ceded to Colombia on September 7, 1981, by treaty.

- Swan Islands (1863–1972): claimed under Guano Islands Act. Ceded to Honduras in 1972, by treaty.

Former unincorporated territories of the United States under military government

Puerto Rico (April 11, 1899 – May 1, 1900): civil government operations began

Puerto Rico (April 11, 1899 – May 1, 1900): civil government operations began Philippines (August 14, 1898[44] – July 4, 1901): civil government operations began

Philippines (August 14, 1898[44] – July 4, 1901): civil government operations began Guam (April 11, 1899 – July 1, 1950): civil government operations began

Guam (April 11, 1899 – July 1, 1950): civil government operations began

Areas formerly administered by the United States

Cuba (April 11, 1899 – May 20, 1902): sovereignty recognized as the independent Republic of Cuba.

Cuba (April 11, 1899 – May 20, 1902): sovereignty recognized as the independent Republic of Cuba. Philippines (August 14, 1898 – July 4, 1946): sovereignty recognized as the Republic of the Philippines.

Philippines (August 14, 1898 – July 4, 1946): sovereignty recognized as the Republic of the Philippines. Veracruz: occupied by the United States from April 21, 1914 to November 23, 1914, consequential to the Tampico Affair following the Mexican Revolution of 1910–1929.

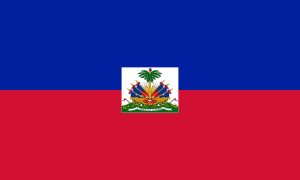

Veracruz: occupied by the United States from April 21, 1914 to November 23, 1914, consequential to the Tampico Affair following the Mexican Revolution of 1910–1929. Haiti: occupied by the United States from 1915 to 1934 and later under the authority of the United Nations from 1999 to the 2000s.

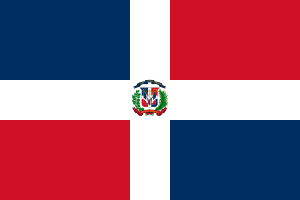

Haiti: occupied by the United States from 1915 to 1934 and later under the authority of the United Nations from 1999 to the 2000s. Dominican Republic occupied by the United States from 1916 to 1924 and again from 1965 to 1966.

Dominican Republic occupied by the United States from 1916 to 1924 and again from 1965 to 1966. Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands (1947–1986): liberated in World War II, included the "Compact of Free Association" nations (the Republic of the Marshall Islands, the Federated States of Micronesia, and the Republic of Palau) and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands

Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands (1947–1986): liberated in World War II, included the "Compact of Free Association" nations (the Republic of the Marshall Islands, the Federated States of Micronesia, and the Republic of Palau) and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands Ryukyu Islands including Okinawa (U.S. occupation: 1952–1972, after World War II): returned to Japan under the Agreement Between the United States of America and Japan concerning the Ryukyu Islands and the Daito Islands.[45]

Ryukyu Islands including Okinawa (U.S. occupation: 1952–1972, after World War II): returned to Japan under the Agreement Between the United States of America and Japan concerning the Ryukyu Islands and the Daito Islands.[45] Nanpo Islands (1945–1968): Occupied after World War II, Returned to Japanese control by mutual agreement.

Nanpo Islands (1945–1968): Occupied after World War II, Returned to Japanese control by mutual agreement. Marcus Island (or Minamitorishima) (1945–1968): Occupied during World War II, returned to Japan by mutual agreement.

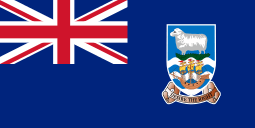

Marcus Island (or Minamitorishima) (1945–1968): Occupied during World War II, returned to Japan by mutual agreement. Falkland Islands (1831–1832): Brief landing party and raid by the U.S. Navy warship USS Lexington. Now administered as a British Overseas Territory by the United Kingdom and claimed by Argentina.

Falkland Islands (1831–1832): Brief landing party and raid by the U.S. Navy warship USS Lexington. Now administered as a British Overseas Territory by the United Kingdom and claimed by Argentina.

Other zones

- United States occupation of Greenland (1941–1945)[46]

- United States occupation of Iceland during World War II (1941–1946),[46] retained a military base until 2006.

- American Occupation Zones in Allied-occupied Austria and Vienna (1945–1955)

- American Occupation Zone in West Berlin (1945–1990)

- American Occupation Zones of the Allied Occupation Zones in Germany (1945–1949)

- Allied Military Government for Occupied Territories in full force in Allied-controlled sections of Italy from Invasion of Sicily in July 1943 until the armistice with Italy in September 1943. AMGOT continued in newly liberated areas of Italy until the end of World War II. Also existed in combat zones of Allied nations such as France.

- Free Territory of Trieste (1947–1954) The U.S. co-administered a portion of the Free Territory between the Kingdom of Italy and the former Kingdom of Yugoslavia after World War II along with the United Kingdom.

- Occupation of Japan (1945–1952) after World War II.

- U.S. participation in the Occupation of the Rhineland (Germany) (1918–1921)

- South Korea (U.S. occupation of the south of the 38th parallel north in Korea in 1945–1948). The region is slightly different from the current practical boundary of the Republic of Korea (South Korea) since the ceasefire of the Korean War. See also Division of Korea.

- Coalition Provisional Authority Iraq (2003–2004)

- Green zone Iraq (March 20, 2003 – December 31, 2008)[47]

- Clipperton Island (1944–1945), occupied territory; returned to France on October 23, 1945.

- Grenada invasion and occupation (1983)

See also

- Enabling act (United States)

- Extreme points of the United States

- Hawaiian Organic Act

- Historic regions of the United States

- Insular Cases

- List of U.S. colonial possessions

- Organic Acts of 1845–46

- Organized incorporated territories of the United States

- Political divisions of the United States

- Political status of Puerto Rico

- Territorial Clause

- Territories of the United States on stamps

- Unincorporated territories of the United States

- United States Minor Outlying Islands

- United States territory

- Unorganized territories

References

- ↑ "Definition of Terms - 1120 Acquisition of U.S. Nationality in U.S. Territories and Possessions" (PDF). U.S. Department of State Foreign Affairs Manual Volume 7- Consular Affairs. U.S. Department of State.

- ↑ "Definitions of Insular Area Political Organizations". U.S. Department of the Interior.

- ↑ US General Accounting Office, U.S. Insular Areas: Application of the U.S. Constitution, November 1997, pp. 8, 14, 27, viewed September 3, 2015.

- ↑ US State Department, Common Core Document of the United States of America, report to the UN Committee on Human Rights, December 30, 2011, sec. 82, 83, 84, 85, 86, 87, viewed September 3, 2015. American Samoa, Guam and U.S. Virgin Islands appear on the UN non-self-governing territories list, viewed September 3, 2015.

- ↑ U.S. General Accounting Office Report, U.S. Insular Areas: application of the U.S. Constitution, November 1997, p. 1, 6, 39n. viewed April 6, 2016.

- ↑ U.S. State Department, Dependencies and Areas of Special Sovereignty Chart, under "Sovereignty", lists nine places under United States sovereignty administered by the Interior Department in Washington, D.C.: Baker Island, Howland Island, Jarvis Island, Johnston Atoll, Kingman Reef, Midway Islands, Navassa Island, Palmyra Atoll, and Wake Island.

- ↑ Sparrow, Bartholomew H., in Levinson, S. and Sparrow, B. H., The Louisiana Purchase And American Expansion, 1803–1898 2005. ISBN 0-7425-4984-4 p.232. viewed December 2, 2012. "… At present, the United States includes the Caribbean and Pacific territories, the District of Columbia and, of course, the fifty states."

- 1 2 7 FAM 1112. State Department Foreign Affairs Manual (FAM) 7-Consular Affairs. Viewed January 12, 2016.

- ↑ Executive Order 13423 Sec. 9. (l). "The 'United States' when used in a geographical sense, means the fifty states, the District of Columbia, the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, Guam, American Samoa, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and the Northern Mariana Islands, and associated territorial waters and airspace."

- ↑ U.S. State Department, Dependencies and Areas of Special Sovereignty Chart, under "Sovereignty", lists five places under United States sovereignty administered by a local 'Administrative Center', with 'Short form names', American Samoa, Guam, Northern Mariana Islands, Puerto Rico, Virgin Islands, U.S.

- ↑ Nativity by Place of Birth and Citizenship Status, United States Census, 2010.

- 1 2 7 FAM 1111(b). State Department Foreign Affairs Manual (FAM) 7-Consular Affairs. However, as reported in Samoa lawsuit, Newsweek, July 13, 2012. viewed December 16, 2012. Certain native Samoan objections arise opposing U.S. citizenship at birth as meaning all of the U.S. Constitution applies everywhere in American Samoa. That would prevent certain communal land ownership rules in American Samoa favoring those with Samoan blood.

- 1 2 House Learn webpage. Viewed January 26, 2013.

- ↑ Application of the U.S. Constitution, GAO Report, U.S. Insular Areas, November 1997, (p. 26–28).

- ↑ viewed August 10, 2015.

- ↑ The Green Papers, 2016 Presidential primaries, caucuses and conventions, viewed September 3, 2015.

- ↑ Definitions of insular area political organizations, Office of Insular Affairs, U.S. Department of the Interior, retrieved 2007-11-14

- ↑ Consejo de Salud Playa de Ponce v. Johnny Rullan, Secretary of Health of the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, pages 6–7 (PDF), The United States District Court for the District of Puerto Rico, retrieved 4 February 2010

- ↑ The Insular Cases: The Establishment of a Regime of Political Apartheid (2007) Juan R. Torruella (PDF), retrieved 5 February 2010

- ↑ "FindLaw's United States Supreme Court case and opinions.".

- ↑ Balzac v. Porto Rico, 258 U.S. 298 (1922) (opinion full text).

- ↑ "Treaty with Russia". Library of Congress. March 30, 1867. Article III.

- ↑ "FindLaw's United States Supreme Court case and opinions.".

- ↑ The Insular Cases: The Establishment of a Regime of Political Apartheid" (2007) Juan R. Torruella Pages 318–319. (PDF), retrieved 7 February 2010

- ↑ "Dorr v. United States 195 U.S. 138 (1904)".

- 1 2 3 "FindLaw's United States Supreme Court case and opinions.".

- ↑ U.S. Const. art. IV, § 3, cl. 2 ("The Congress shall have Power to dispose of and make all needful Rules and Regulations respecting the Territory or other Property belonging to the United States...").

- ↑ "AUSTRALIA-OCEANIA :: UNITED STATES PACIFIC ISLAND WILDLIFE REFUGES (TERRITORIES OF THE US)". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency.

- ↑ "DOI Office of Insular Affairs (OIA) - Palmyra Atoll". 31 October 2007.

- ↑ "Palmyra Atoll". U.S. Department of the Interior Office of Insular Affairs. Retrieved 2010-06-23.

- ↑ Consejo de Salud Playa Ponce v. Johnny Rullan, p.28: "The Congressional incorporation of Puerto Rico throughout the past century has extended the entire Constitution to the island ...."

- ↑ Hon. Gustavo A. Gelpi, "The Insular Cases: A Comparative Historical Study of Puerto Rico, Hawai'i, and the Philippines", The Federal Lawyer, March/April 2011. http://www.aspira.org/files/legal_opinion_on_pr_insular_cases.pdf p. 25: "In light of the [Supreme Court] ruling in Boumediene, in the future the Supreme Court will be called upon to reexamine the Insular Cases doctrine as applied to Puerto Rico and other U.S. territories."

- ↑ accessed 26 January 2013: "Puerto Rico is a self-governing, unincorporated territory of the United States located in the Caribbean".

- ↑ The revised constitution was approved on June 2, 1967 by Stewart L. Udall, then U.S. Secretary of the Interior, under authority granted on June 29, 1951. It became effective on July 1, 1967.[35]

- ↑ IBP USA (2009), SAMOA American Country Study Guide: Strategic Information and Developments, Int'l Business Publications, pp. 49–64, ISBN 978-1-4387-4187-1, retrieved 2011-10-20

- 1 2 3 4 Moore, John Bassett (1906). "A Digest of International Law as Embodied in Diplomatic Discussions, Treaties and Other International Agreements, International Awards, the Decisions of Municipal Courts, and the Writings of Jurists and Especially in Documents, Published and Unpublished, Issued by Presidents and Secretaries of State of the United States, the Opinions of the Attorneys-General, and the Decisions of Courts, Federal and State". Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. pp. 566–580.

- 1 2 3 4 "Acquisition Process of Insular Areas". United States Department of the Interior Office of Insular Affairs. Retrieved July 15, 2016.

- 1 2 3 Exec. Order No. 7368 (May 13, 1936; in English) President of the United States

- ↑ "Kingman Reef". Office of Insular Affairs. Retrieved July 15, 2016.

- ↑ "Wake Island". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency.

- 1 2 International Court of Justice (2012). "Territorial and maritime dispute (Nicaragua vs Colombia)" (PDF). Retrieved 2013-06-29.

- ↑ Agreement Between the United States and Cuba for the Lease of Lands for Coaling and Naval stations, The Avalon Project at Yale Law School, February 23, 1903, retrieved 2008-04-02

- ↑ Michael Ratner; Ellen Ray (2004). Guantanamo: What the World Should Know. Chelsea Green Publishing. p. xiv;. ISBN 978-1-931498-64-7.

- ↑ Zaide, Sonia M. (1994). The Philippines: A Unique Nation. All-Nations Publishing Co., Inc. p. 279. ISBN 9716420714. Retrieved October 20, 2011.

- ↑ Okinawa Reversion Agreement – 1971, The Contemporary Okinawa Website. Accessed 5 June 2007.

- 1 2 Committee, America First (1 January 1990). "In Danger Undaunted: The Anti-interventionist Movement of 1940-1941 as Revealed in the Papers of the America First Committee". Hoover Institution Press. p. 331 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Campbell Robertson; Stephen Farrell (December 31, 2008), Green Zone, Heart of U.S. Occupation, Reverts to Iraqi Control, The New York Times

External links

- FindLaw: Downes v. Bidwell, 182 U.S. 244 (1901) regarding the distinction between incorporated and unincorporated territories

- FindLaw: People of Puerto Rico v. Shell Co., 302 U.S. 253 (1937) regarding application of U.S. law to organized but unincorporated territories

- FindLaw: United States v. Standard Oil Company, 404 U.S. 558 (1972) regarding application of U.S. law to unorganized unincorporated territories

- Television Stations in U.S. Territories

- Unincorporated Territory

- Office of Insular Affairs

- Application of the U.S. Constitution in U.S. Insular Areas

- Department of the Interior Definitions of Insular Area Political Organizations

- United States District Court decision addressing the distinction between Incorporated vs Unincorporated territories