Invasion of Grenada

| Operation Urgent Fury | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Cold War | |||||||

A Sikorsky CH-53D Sea Stallion helicopter of the U.S. Marine Corps hovers above the ground near an abandoned Soviet ZU-23-2 anti-aircraft weapon during the invasion of Grenada in 1983. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

United States: 7,300 CPF: 353 |

Grenada: ~1,200 Cuba: 780[3]:6, 26, 62 Soviet Union: 49 North Korea: 24[2] East Germany: 16 Bulgaria: 14 Libya: 3 or 4 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

United States: 19 killed[4] 116 wounded[3]:6, 62 9 helicopters lost |

Grenada: | ||||||

|

| |||||||

The Invasion of Grenada was a 1983 United States–led invasion of the Caribbean island nation of Grenada, with a population of about 91,000 located 160 kilometres (99 mi) north of Venezuela, that resulted in a U.S. victory within a matter of weeks. Codenamed Operation Urgent Fury, it was triggered by the internal strife within the People's Revolutionary Government that resulted in the house arrest and the execution of the previous leader and second Prime minister of Grenada Maurice Bishop, and the establishment of a preliminary government, the Revolutionary Military Council with Hudson Austin as Chairman. The invasion resulted in the appointment of an interim government, followed by democratic elections in 1984. The country has remained a democratic nation since then.

Grenada gained independence from the United Kingdom in 1974. The leftist New Jewel Movement seized power in a coup in 1979 under Maurice Bishop, suspending the constitution and detaining a number of political prisoners. In 1983, an internal power struggle began over Bishop's relatively moderate foreign policy approach, and on October 19, hard-line Stalinists captured and executed Bishop, his partner Jacqueline Creft, along with three cabinet ministers and two union leaders. Subsequently, following appeals by the Organization of Eastern Caribbean States and the Governor-General of Grenada, Paul Scoon, the Reagan Administration in the U.S. quickly decided to launch a military intervention. From the U.S. perspective, a justification for the intervention was in part explained as "concerns over the 600 U.S. medical students on the island" and fears of a repeat of the Iran hostage crisis.

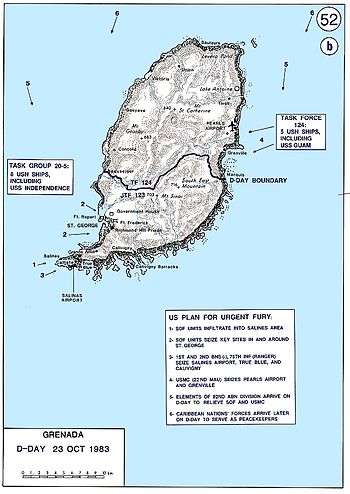

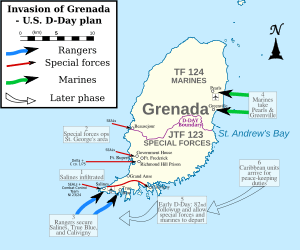

The U.S. invasion began six days after Bishop's death, on the morning of 25 October 1983. The U.S. Army's Rapid Deployment Force (1st, 2nd Ranger Battalions and 82nd Airborne Division Paratroopers), U.S. Marines, U.S. Army Delta Force, and U.S. Navy SEALs and other combined forces constituted the 7,600 troops from the United States, Jamaica, and members of the Regional Security System (RSS)[7] defeated Grenadian resistance after a low-altitude airborne assault by the 75th Rangers on Point Salines Airport on the southern end of the island, and a Marine helicopter and amphibious landing occurred on the northern end at Pearl's Airfield shortly afterward. The military government of Hudson Austin was deposed and replaced by a government appointed by Governor-General Paul Scoon until elections were held in 1984.

The invasion was criticized by several countries including Canada. British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher privately disapproved of the mission and the lack of notice she received, but publicly supported the intervention.[8] The United Nations General Assembly, on 2 November 1983 with a vote of 108 to 9, condemned it as "a flagrant violation of international law".[9] Conversely, it enjoyed broad public support in the United States[10] and, over time, a positive evaluation from the Grenadian population, who appreciated the low civilian casualties and the return to democratic elections in 1984.[11][12] The U.S. awarded more than 5,000 medals for merit and valor.[13][14]

The date of the invasion is now a national holiday in Grenada, called Thanksgiving Day. The commemoration was due to several political prisoners that were freed after the invasion, and subsequently elected into office. A truth and reconciliation commission was launched in 2000, re-examining some of the controversies of the era; in particular, they made an unsuccessful attempt to find Bishop's body, which was disposed of under Hudson Austin's orders and never found.

For the U.S., the invasion also highlighted problematic issues with communication and coordination between the different branches of the United States military when operating together as a joint force, contributing to investigations and sweeping changes in the form of the Goldwater-Nichols Act and other reorganizations.

Background

Sir Eric Gairy had led Grenada to independence from the United Kingdom in 1974. His term in office coincided with civil strife in Grenada. The political environment was highly charged and although Gairy—head of the Grenada United Labour Party—claimed victory in the general election of 1976, the opposition did not accept the result as legitimate. The civil strife took the form of street violence between Gairy's private army, the Mongoose Gang, and gangs organized by the New Jewel Movement (NJM). In the late 1970s the NJM began planning to overthrow the government. Party members began to receive military training outside of Grenada. On 13 March 1979, while Gairy was out of the country, the NJM—led by Maurice Bishop—launched an armed revolution and overthrew the government, establishing the People's Revolutionary Government.

Airport

The Bishop government began constructing the Point Salines International Airport with the help of Britain, Cuba, Libya, Algeria, and other nations. The airport had been first proposed by the British government in 1954, when Grenada was still a British colony. It had been designed by Canadians, underwritten by the British government, and partly built by a London firm. The U.S. government accused Grenada of constructing facilities to aid a Soviet-Cuban military buildup in the Caribbean based upon the 9,000-foot length runway, which could accommodate the largest Soviet aircraft like the An-12, An-22, and the An-124, which would enhance the Soviet and Cuban transportation of weapons to Central American insurgents and expand Soviet regional influence. Bishop's government claimed that the airport was built to accommodate commercial aircraft carrying tourists, pointing out that such jets could not land at Pearl's Airstrip on the island's north end (5,200 feet) and could not be expanded because its runway abutted a mountain at one end and the ocean at the other.

In 1983, then-member of the United States House of Representatives Ron Dellums (D, California), traveled to Grenada on a fact-finding mission, having been invited by the country's prime minister. Dellums described his findings before Congress:

... based on my personal observations, discussion and analysis of the new international airport under construction in Grenada, it is my conclusion that this project is specifically now and has always been for the purpose of economic development and is not for military use. ... It is my thought that it is absurd, patronizing, and totally unwarranted for the United States government to charge that this airport poses a military threat to the United States' national security.[15]

In March 1983, President Ronald Reagan began issuing warnings about the threat posed to the United States and the Caribbean by the "Soviet-Cuban militarization" of the Caribbean as evidenced by the excessively long airplane runway being built, as well as intelligence sources indicating increased Soviet interest in the island. He said that the 9,000-foot (2,700 m) runway and the numerous fuel storage tanks were unnecessary for commercial flights, and that evidence pointed that the airport was to become a Cuban-Soviet forward military airbase.[16]

On 29 May 2009 the Point Salines International Airport was officially renamed the Maurice Bishop International Airport, in honour of the slain pre-coup leader Maurice Bishop by the Government of Grenada.[17][18]

October 1983

On 16 October 1983, a party faction led by Deputy Prime Minister Bernard Coard seized power. Bishop was placed under house arrest. Mass protests against the action led to Bishop's escaping detention and reasserting his authority as the head of the government. Bishop was eventually captured and murdered, along with his pregnant partner, and several government officials and union leaders loyal to him. The army under Hudson Austin then stepped in and formed a military council to rule the country. The governor-general, Paul Scoon, was placed under house arrest. The army announced a four-day total curfew where anyone seen on the streets would be subject to summary execution.

The Organization of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS), as well as the nations of Barbados and Jamaica, appealed to the United States for assistance.[3] It was later announced that Grenada's governor-general, Paul Scoon, had actually requested the invasion through secret diplomatic channels and for his safety it had not been made public.[19] Scoon was well within his rights to take this action under the reserve powers vested in the Crown.[20] On Saturday 22 October 1983, the Deputy High Commissioner in Bridgetown, Barbados visited Grenada and reported that Sir Paul Scoon was well and "did not request military intervention, either directly or indirectly".[21]

On 25 October, Grenada was invaded by the combined forces of the United States and the Regional Security System (RSS) based in Barbados, in an operation codenamed Operation Urgent Fury. The U.S. stated this was done at the request of the prime ministers of Barbados and Dominica, Tom Adams and Dame Eugenia Charles, respectively. Nonetheless, the invasion was highly criticized by the governments in Canada, Trinidad and Tobago, and the United Kingdom. The United Nations General Assembly condemned it as "a flagrant violation of international law"[22] by a vote of 108 in favour to 9, with 27 abstentions.[23] The United Nations Security Council considered a similar resolution, which failed to pass when vetoed by the United States.

First day of the invasion

The invasion commenced at 05:00 on 25 October 1983. American forces refuelled and departed from the Grantley Adams International Airport on the nearby Caribbean island of Barbados before daybreak en route to Grenada.[24] It was the first major operation conducted by the U.S. military since the Vietnam War. Vice Admiral Joseph Metcalf, III, Commander Second Fleet, was the overall commander of U.S. forces, designated Joint Task Force 120, which included elements of each military service and multiple special operations units. Fighting continued for several days and the total number of U.S. troops reached some 7,000 along with 300 troops from the OAS. The invading forces encountered about 1,500 Grenadian soldiers and about 700 armed Cuban nationals manning defensive positions. Grenada's security forces possessed no tanks, only 8 BTR-60PB armored personnel carriers and 2 BRDM-2 scout cars they had received from the Soviet Union in February 1981.[25][26] Their arsenal also included twelve ZU-23 anti-aircraft guns, DShK heavy machine guns, and a limited number of M37 82mm mortars and RPG-7 launchers.

The main objectives on the first day of the invasion were the capture of the Point Salines International Airport by the 75th Ranger Regiment, to permit the 82nd Airborne Division to land reinforcements on the island; the capture of Pearls Airport by the 8th Marine Regiment; and the rescue of the U.S. students at the True Blue Campus of St. George's University. In addition, a number of special operations missions were undertaken to obtain intelligence and secure key individuals and equipment. In general, many of these missions were plagued by inadequate intelligence, planning, and accurate maps of any kind (the American forces mostly relied upon tourist maps).

Cuban forces in Grenada

The nature of the Cuban military presence in Grenada was more complex than initially suggested.[27] As in Angola, Ethiopia, and other nations with large contingents of Cuban troops, the line between civilians and military personnel was blurred. For example, Fidel Castro often described Cuban construction crews deployed overseas as "workers and soldiers at the same time"; the duality of their role being consistent with Havana's 'citizen soldier' tradition.[27] At the time of the invasion, there were an estimated 784 Cuban nationals on the island.[28] At least 636 were formally listed as construction workers, another 64 as military personnel, and 18 as dependents. The remainder claimed to be either medical staff or teachers.[28] Colonel Pedro Tortoló Comas, the highest ranking Cuban military official in Grenada in 1983, later stated that he'd issued weapons and ammunition to many of the construction workers for self-defense.[28] According to journalist Bob Woodward in his book Veil, captured "military advisors" from socialist countries were actually accredited diplomats and included their dependents. None, Woordward claimed, took any actual part in the fighting.[29] Other historians have asserted that most of the supposed civil technicians on Grenada were Cuban special forces and combat engineers.[30]

Once the invasion began, Cuba's lack of adequate naval transport facilities and its ongoing military commitments in Africa made it difficult to reinforce Grenada on such short notice.[28] Nevertheless, Cuban nationals were expressly forbidden to surrender to U.S. forces.[28]

Navy SEAL reconnaissance missions

U.S. Special Operations Forces were deployed to Grenada beginning on October 23, before the invasion on October 25. U.S. Navy SEALs from SEAL Team 4 were airdropped at sea with 2 PBLs (patrol boat, light) to perform a reconnaissance mission on Point Salines, but delays in the insertion pushed the mission into the dead of night in the middle of a storm resulting in four of the SEALs drowning upon landing. The motor on the boat used by the survivors flooded while evading a patrol boat, causing the mission to be aborted. A SEAL mission on the 24th also was made unsuccessful due to harsh weather, resulting in little intelligence being gathered in advance of the impending U.S. intervention.[31]

Air assault on Point Salines

At midnight on October 24, the A and B companies of the 1st Battalion of the 75th Ranger Regiment embarked on C-130s at Hunter Army Airfield to perform an air assault landing on Point Salines International Airport. Initially intending to land at the airport and then disembark, the Rangers had to switch abruptly to a parachute landing when it was learned mid-flight that the runway was obstructed. The air drop began at 5:30 AM on the 25th in the face of moderate resistance from ZU-23 anti-aircraft guns and several BTR-60 APCs, the latter of which were knocked out by 90mm recoilless rifles. AC-130 gunships also provided support for the landing. Cuban construction vehicles were commandeered to help clear the airfield, and one was even used to provide mobile cover for the Rangers as they moved to seize the heights surrounding the airfield.[32]

By 10 AM, the air strip had been cleared of obstructions and transport planes were able to land directly and unload additional reinforcements, including M151 Jeeps and elements of the Caribbean Peace Force, which were assigned to guard the perimeter and detainees. Starting at 2 PM, units from the 82nd Airborne Division, under MG Edward Trobaugh, began landing at Point Salines, including battalions of the 325th Infantry Regiment. At 3:30 PM, a counterattack by 3 BTR-60s of the Grenadian Army Motorized Company was repelled with fire from recoilless rifles and an AC-130.[33]

The Rangers proceeded to fan out and secure the surrounding area, including negotiating the surrender of over a hundred Cubans in an aviation hangar. However, a Jeep-mounted Ranger patrol became lost searching for True Blue Campus and was ambushed, suffering 4 KIA. The Rangers eventually secured True Blue campus and its students, where they were shocked to discover only 140 students, and were told that more were located at another campus in Grand Anse. In all, the Rangers lost 5 men on the first day, but succeeded in securing the Point Salines and the surrounding area.[32]

Capture of Pearls Airport

Close to midnight on October 24, a platoon of Navy SEALs, from SEAL Team 4, under Lieutenant Mike Walsh approached the beach near Pearls Airport. After evading patrol boats and overcoming stormy weather, they determined that the beach was undefended but unsuitable for an amphibious landing. The 2nd Battalion of the 8th Marine Regiment then landed south of Pearls Airport using CH-46 Sea Knight and CH-53 Sea Stallion helicopters at 5:30 AM on the 25th. The Marines proceeded to capture Pearl Airport, encountering only light resistance, including a DShK machine gun which was destroyed by a Marine AH-1 Cobra.[34]

Raid on Radio Free Grenada

On the early morning of the 25th, another team from SEAL Team 6 was inserted by UH-60 Blackhawk helicopters to capture Radio Free Grenada, in order to use it for PsyOps purposes. Although the station was captured unopposed, a counter-attack with armored cars forced the lightly-armed SEALs to retreat in the jungle, destroying the radio transmitter as they left.[31]

Raids on Fort Rupert and Richmond Hill Prison

On October 25, raids were undertaken by Delta Force and C Company of the 75th Ranger Regiment, embarked upon MH-60 and MH-6 Little Bird helicopters of Task Force 160 to capture Fort Ruppert, where the leadership of the Revolutionary Council was believed to reside, and Richmond Hill Prison, where many political prisoners were being held. The raid on Richmond Hill Prison lacked vital intelligence, including the fact that multiple anti-aircraft guns were located around and above the prison, and that the prison was located on a steep hill without room for a helicopter to land. Withering anti-craft fire wounded passengers and crew, and forced one MH-60 helicopter to crash land, causing another helicopter to land next to it to protect the survivors. One pilot was killed, and the Delta force operators had to be relieved by a separate force of Rangers. The raid on Fort Rupert, however, was successful in capturing several leaders of the People's Revolutionary Government.[33]

Mission to rescue Governor General Scoon

The last major special operation was a mission to rescue and evacuate Governor General Paul Scoon from his mansion in Saint George, Grenada. The mission departed late at 5:30 AM on October 25 from Barbados, resulting in the Grenadian forces being already aware of the U.S. invasion when it landed and secured Governor Scoon. Although the SEAL team's entry into the mansion went unopposed, a large local counterattack led by BTR-60 armored personnel carriers trapped the SEALs and the governor inside. AC-130 gunships, A-7 Corsair strike planes, and AH-1 Cobra attack helicopters were called in to support the besieged SEALs, but the SEALs remained trapped for the next 24 hours.

At 7 PM on October 25, 250 U.S. Marines from G Company of the 22nd Marine Assault Unit equipped with Amphibious Assault Vehicles and four M60 Patton tanks landed at Grand Mal Bay, and relieved the Navy SEALs the following morning on October 26, allowing Governor Scoon, his wife and nine aides to be safely evacuated at 10 AM that day. The Marine tank crews continued advancing in the face of sporadic resistance, knocking out a BRDM-2 armored car.[26] G Company subsequently defeated and overwhelmed the Grenadian defenders at Fort Frederick.[34]

Airstrikes

Airstrikes were undertaken by U.S. Navy A-7 Corsairs as well as U.S. Marine AH-1 Cobra attack helicopters against Fort Rupert and Fort Frederick. An A-7 raid on Fort Frederick targeting anti-aircraft guns hit a nearby mental hospital, killing 18 civilians.[3]:62 Two Marine AH-1T Cobras and a UH-60 Blackhawk were shot down in a raid against Fort Frederick, resulting in five KIA.[34]

Second day of the invasion

On the second day, U.S. Commander on the ground, General Trobaugh of the 82nd Airborne Division, had two goals: securing the perimeter around Salines Airport and rescuing the U.S. students they had learned were at the campus in Grand Anse. Because of the lack of undamaged helicopters after the losses on the first day, the Army had to delay pursuing the second objective until it made contact with Marine forces.

Attack on the Cuban compound

Early in the morning of the 26th, a patrol from the 2nd Battalion of the 325th Infantry Regiment was ambushed by Cuban forces near the village of Calliste, suffering six wounded and two killed in the ensuing firefight, including the commander of Company B. Following that, U.S. Navy air strikes and an artillery bombardment by 105mm howitzers targeting the main Cuban encampment eventually led to their surrender at 8:30. US forces pushed on into the village of Frequente, where they discovered a Cuban weapon cache supposedly sufficient to equip "six battalions." There, a reconnaissance platoon mounted of gun-jeeps was ambushed by Cuban forces, but return fire from the jeeps, and mortars from a nearby infantry unit inflicted four casualties on the ambushers at no U.S. loss. Cuban resistance largely ended after these engagements.[32]

'Rescue' at Grand Anse

In the afternoon of the 26, US Rangers of the 2nd Battalion of the Ranger Regiment mounted U.S. Marine CH-46 Sea Knight helicopters to launch an air assault on the Grand Anse campus. The campus guards offered light resistance before fleeing, wounding one Ranger, but one of the helicopters crashed on the approach after its blade hit a palm tree. The 233 U.S. students present were successfully evacuated into CH-53 Sea Stallion helicopters, but informed the U.S. commanders that there was a third campus with U.S. students at Prickly Bay.[34] A squad of 11 Rangers was accidentally left behind, ultimately egressing on a rubber raft which was picked up by the USS Caron at 11 PM.[33]

Third day of the invasion and after

By October 27, organized resistance was rapidly diminishing, but the American forces did not yet realize this. The Marine 22nd MAU and 8th Regiment continued advancing along the coast and capturing additional towns, meeting little resistance, although one patrol did encounter a single BTR-60 during the night and dispatched it with their M72 LAW. The 325th Infantry Regiment advanced toward Saint George, capturing Grand Anse (where they discovered 20 U.S. students they had missed the first day), the town of Ruth Howard, and the capital of Saint George, meeting only scattered resistance. An A-7 airstrike called by an Air-Naval Gunfire Liaison team accidentally hit the command post of the 2nd Brigade, wounding 17 troops, one of whom died of wounds.[32]

The Army had reports that PRA forces were amassing at the Calivigny barracks, only five kilometers miles away from the Point Salines airfield. They therefore organized an air assault by the 2nd Battalion of the 75th Ranger Regiment which would be preceded by a heavy preparatory bombardment by field howitzers (which mostly missed, their shells falling into ocean), A-7 Corsairs, AC-130s, and the USS Caron. However, when the Blackhawk helicopters began dropping off troops near the barracks, they approached at too high a speed, and one of them crash-landed and the two behind it collided into it, killing three and wounding four. Ironically, the barracks were deserted.[33]

In the following days, resistance ended entirely and the Army and Marines spread across the island, arresting PRA officials, seizing caches of weapons, and seeing to the repatriation of Cuban engineers.

On November 1, two companies from the 22nd Marine Amphibious Unit made a combined sea and helicopter landing on the island of Carriacou 17 miles (27 km) to the northeast of Grenada. The nineteen Grenadan soldiers defending the island surrendered without a fight. This was the last military action of the campaign.[35]

Outcome

Official U.S. sources state that some of their opponents were well prepared and well positioned and put up stubborn resistance, to the extent that the U.S. called in two battalions of reinforcements on the evening of 26 October. The total naval and air superiority of the coalition forces—including helicopter gunships and naval gunfire support as well as members of reserve Navy SEALs, had overwhelmed the defenders.

Nearly 8,000 soldiers, sailors, airmen, and Marines had participated in Operation Urgent Fury along with 353 Caribbean allies of the Caribbean Peace Forces. U.S. forces sustained 19 killed and 116 wounded; Cuban forces sustained 25 killed, 59 wounded, and 638 combatants captured. Grenadian forces suffered 45 dead and 358 wounded; at least 24 civilians were also killed, 18 of whom died in the accidental bombing of a Grenadian mental hospital.[3]:62 The U.S. also destroyed a significant amount of Grenada's military hardware, including six APCs and an armored car.[26] A second armored car was impounded and later shipped back to Marine Corps Base Quantico for inspection.[36]

Reaction in the United States

A month after the invasion, Time magazine described it as having "broad popular support." A congressional study group concluded that the invasion had been justified, as most members felt that U.S. students at the university near a contested runway could have been taken hostage as U.S. diplomats in Iran had been four years previously. The group's report caused House Speaker Tip O'Neill to change his position on the issue from opposition to support.[10]

However, some members of the study group dissented from its findings. Congressman Louis Stokes, D-Ohio, stated: "Not a single American child nor single American national was in any way placed in danger or placed in a hostage situation prior to the invasion." The Congressional Black Caucus denounced the invasion and seven Democratic congressmen, led by Ted Weiss, introduced an unsuccessful resolution to impeach Ronald Reagan.[10]

In the evening of 25 October 1983 by telephone, on the newscast Nightline, anchor Ted Koppel spoke to medical students on Grenada who stated that they were safe and did not feel their lives were in danger. The next evening, again by telephone, medical students told Koppel how grateful they were for the invasion and the Army Rangers, which probably saved their lives. State Department officials had assured the medical students that they would be able to complete their medical school education in the United States.[37][38]

International reaction

On 2 November 1983 by a vote of 108 in favour to 9 voting against (Antigua and Barbuda, Barbados, Dominica, El Salvador, Israel, Jamaica, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, and the United States), with 27 abstentions, the United Nations General Assembly adopted General Assembly Resolution 38/7, which "deeply deplores the armed intervention in Grenada, which constitutes a flagrant violation of international law and of the independence, sovereignty and territorial integrity of that State."[9] It went on to deplore “the death of innocent civilians” the “killing of the prime Minister and other prominent Grenadians” and called for an “immediate cessation of the armed intervention” and demanded “that free elections be organized”.

This was the first military rollback of a Communist nation. The Soviet Union said that Grenada had for a long time been the object of United States threats, that the invasion violated international law, and that no small nation not to the liking of the United States would find itself safe if the aggression against Grenada were not rebuffed. The governments of some countries stated that the United States intervention was a return to the era of barbarism. The governments of other countries said the United States by its invasion had violated several treaties and conventions to which it was a party.[39]

A similar resolution was discussed in the United Nations Security Council and although receiving widespread support it was ultimately vetoed by the United States.[40][41][42] President of the United States Ronald Reagan, when asked if he was concerned by the lopsided 108–9 vote in the UN General Assembly said "it didn't upset my breakfast at all."[43]

Grenada is part of the Commonwealth of Nations and, following the invasion, it requested help from other Commonwealth members. The intervention was opposed by the United Kingdom, Trinidad and Tobago, and Canada, among others.[3]:50 British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, a close ally of Reagan on other matters, personally opposed the U.S. invasion. Reagan told her it might happen; she did not know for sure it was coming until three hours before. At 12:30 am on the morning of the invasion, Thatcher sent a message to Reagan:

This action will be seen as intervention by a Western country in the internal affairs of a small independent nation, however unattractive its regime. I ask you to consider this in the context of our wider East/West relations and of the fact that we will be having in the next few days to present to our Parliament and people the siting of Cruise missiles in this country. I must ask you to think most carefully about these points. I cannot conceal that I am deeply disturbed by your latest communication. You asked for my advice. I have set it out and hope that even at this late stage you will take it into account before events are irrevocable.[44][45] (The full text remains classified.)

Reagan told Thatcher before anyone else that the invasion would begin in a few hours, but ignored her complaints. She publicly supported the American action. Reagan phoned to apologize for the miscommunication, and the long-term friendly relationship endured.[46][47]

Aftermath

Following the U.S. victory, the American and Caribbean governments quickly reaffirmed Scoon as Queen Elizabeth II's sole legitimate representative in Grenada--and hence, the only lawful authority on the island. In accordance with Commonwealth constitutional practice, Scoon assumed power as interim head of government, and formed an advisory council which named Nicholas Brathwaite as chairman pending new elections.[19][20] Democratic elections held in December 1984 were won by the Grenada National Party and a government was formed led by Prime Minister Herbert Blaize.

U.S. forces remained in Grenada after combat operations finished in December as part of Operation Island Breeze. Elements remaining, including military police, special forces, and a specialized intelligence detachment, performed security missions and assisted members of the Caribbean Peacekeeping Force and the Royal Grenadian Police Force.

The Point Salines International Airport was renamed in honor of Prime Minister Maurice Bishop on 29 May 2009, the 65th anniversary of his birth.[17][18] Hundreds of Grenadians turned out to commemorate the historical event. Tillman Thomas, Prime Minister of Grenada gave the keynote speech and referred to the renaming as an act of the Grenadian people coming home to themselves.[48] He also hoped that it would help bring closure to a chapter of denial in Grenada's history.

United States

The invasion showed problems with the U.S. government's "information apparatus," which Time described as still being in "some disarray" three weeks after the invasion. For example, the U.S. State Department falsely claimed that a mass grave had been discovered that held 100 bodies of islanders who had been killed by Communist forces.[10] Major General Norman Schwarzkopf, deputy commander of the invasion force, said that 160 Grenadian soldiers and 71 Cubans had been killed during the invasion; the Pentagon had given a much lower count of 59 Cuban and Grenadian deaths.[10] Ronald H. Cole's report for the Joint Chiefs of Staff showed an even lower count.[3]

Also of concern were the problems that the invasion showed with the military. There was a lack of intelligence about Grenada, which exacerbated the difficulties faced by the quickly assembled invasion force. For example, it was not known that the students were actually at two different campuses and there was a thirty-hour delay in reaching students at the second campus.[10] Maps provided to soldiers on the ground were tourist maps on which military grid reference lines were drawn by hand to report locations of units and request artillery and aircraft fire support. They also did not show topography and were not marked with crucial positions. U.S. Navy ships providing naval gunfire and U.S. Marine, U.S. Air Force and Navy fighter/bomber support aircraft providing close air support mistakenly fired upon and killed U.S. ground forces due to differences in charts and location coordinates, data, and methods of calling for fire support. Communications between services were also noted as not being compatible and hindered the coordination of operations. The landing strip was drawn-in by hand on the map given to some members of the invasion force.

A heavily fictionalized account of the invasion from a U.S. military perspective is shown in the 1986 Clint Eastwood motion picture Heartbreak Ridge, in which Marines replaced the actual roles of U.S. Army units. Due to the movie's portrayal of several incompetent officers and NCOs, the Army opted out its military support of the movie.

Goldwater-Nichols Act

Analysis by the U.S. Department of Defense showed a need for improved communications and coordination between the branches of the U.S. forces. U.S. Congressional investigations of many of the reported problems resulted in the most important legislative change affecting the U.S. military organization, doctrine, career progression, and operating procedures since the end of World War II – the Goldwater-Nichols Department of Defense Reorganization Act of 1986 (Pub. L.99–433).

The Goldwater-Nichols Act reworked the command structure of the United States military, thereby making the most sweeping changes to the United States Department of Defense since the department was established in the National Security Act of 1947. It increased the powers of the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and created the concept of a truly unified joint U.S. forces (i.e., Army, Air Force, Marines, and Navy forces organized under one command). One of the first reorganizations resulting from both the Department of Defense analysis and the legislation was the formation of the U.S. Special Operations Command in 1987.

Other

October 25 is a national holiday in Grenada, called Thanksgiving Day, to commemorate the invasion.

St. George's University built a monument on its True Blue Campus to memorialize the U.S. servicemen killed during the invasion, and marks the day with an annual memorial ceremony.

In 2008, the Government of Grenada announced a move to build a monument to honour the Cubans killed during the invasion. At the time of the announcement the Cuban and Grenadian governments are still seeking to locate a suitable site for the monument.[49]

Order of battle

Vice Admiral Joseph Metcalf, III, COMSECONDFLT, became Commander, Joint Task Force 120 (CJTF 120), and commanded units from the Air Force, Army, Navy, and the Marine Corps from the Flag Spaces aboard the MARG flagship USS Guam. CJTF 120 was supported by Rear Admiral Richard E. Berry (COMCRUDESGRU Eight) (Commander Task Group 20), embarked on the aircraft carrier USS Independence. Commanding Officer, USS Guam (Task Force 124) was assigned the mission of seizing the Pearls Airport and the port of Grenville, and of neutralizing any opposing forces in the area.[50] Simultaneously, several SOF elements and Army Rangers (Task Force 123) would secure points at the southern end of the island, including the nearly completed jet airfield under construction near Point Salines. Elements of the 82d Airborne Division (Task Force 121) were designated as follow-on forces and were tasked to follow and assume the security at Point Salines, once seized by Task Force 123. –Task Group 20.5, a carrier battle group built around USS Independence (CV-62), and Air Force elements would support the ground forces.[50]

US ground forces

- US Army 1st and 2nd Ranger Battalions 75th Infantry Regiment conducted a low-level parachute assault to secure Point Salines Airport. Hunter Army Airfield, GA and Ft. Lewis, WA

- US Army 82nd Airborne Division – 2nd Brigade Task Force (325th Airborne Infantry Regiment plus supporting units) and 3rd Brigade Task Force (1st and 2nd Battalions of the 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 1st and 2nd Battalions of the 508th Parachute Infantry Regiment, plus supporting units) 82nd MP General Support Platoon HHC, 313th MI BN (CEWI). Fort Bragg, NC, 1st Battalion of the 319th Field Artillery.

- US Army Co E (Scout), 60th Infantry Regiment, 9th Infantry Division (inactivated in 1984 and assets used to form: Co E (Long Range Surveillance) 109th MI Battalion, 9th Infantry Division (Motorized)), Fort Lewis, WA.

- US Army 27th Engineer Battalion of the 20th Engineer Brigade (Airborne), Fort Bragg, NC

- US Army 548th Engineer Battalion Ft Bragg, NC

- US Army 160th Aviation Battalion Ft Campbell, KY

- US Army 18th Aviation Company, 269th Aviation Battalion Ft. Bragg, NC

- 1st and 2nd 82nd Combat Aviation Battalion, Fort Bragg N.C.

- 1 SQN 17 Air Cavalry Airborne, Fort Bragg N.C.

- US Army 65th MP Company (Airborne), 118th MP Company (Airborne), and HHD, 503rd MP Battalion (Airborne) of the 16th Military Police Brigade (Airborne), XVIII Airborne Corps, Fort Bragg, NC

- US Army 411th MP Company of the 89th Military Police Brigade, III Corps, Ft. Hood, Texas

- US Army 35th Signal Brigade, Ft. Bragg, NC

- US Army 50th Signal Battalion, 35th Signal Brigade, Ft. Bragg, NC

- US Army 319th Military Intelligence Battalion and 519th Military Intelligence Battalion, 525th Military Intelligence Brigade, Fort Bragg, NC

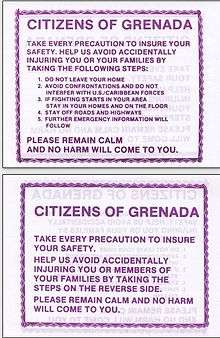

- US Army 9th Psychological Operations Battalion (Airborne) of the 4th Psychological Operations Group (Airborne) – provided loudspeaker support and dissemination of informational pamphlets. Fort Bragg, NC

- US Army 1st Corps Support Command COSCOM, 7th Trans Battalion, 546th LMT Fort Bragg, NC

- US Army 44th Medical Brigade – Personnel from the 44th Medical Brigade and operational units including the 5th MASH were deployed. Fort Bragg, NC

- US Army 82nd Finance Company MPT

- US Marine Corps 22nd Marine Amphibious Unit Camp Lejeune, NC

- US Navy SEAL Team 4 Little Creek, VA and US Navy SEAL Team 6 Virginia Beach, VA

- US Air Force Detachment 1, 507th Tactical Air Control Wing (Fort Bragg, NC) – jump qualified TACPs who were attached to and deployed with the 82d Airborne, Fort Bragg, NC (now the 14th ASOS, part of the 18th Air Support Operations Group)

- US Air Force 21st Tactical Air Support Squadron (Shaw AFB, SC) – jump qualified FACs who were attached to and deployed with Detachment 1, 507th Tac Air Control Wg and the 82d Airborne, Fort Bragg, NC

- US Air Force 5th Weather Squadron, 5th Weather Wing (MAC) Fort Bragg, NC – jump qualified Combat Weathermen who are attached and deployed with the 82nd, now in AFSOC

U.S. Air Force

- 136th Tactical Airlift Wing, Texas Air National Guard – provided C-130 Hercules combat airlift support, cargo and supplies

- Various Air National Guard tactical fighter wings and squadrons – provided A-7D Corsair II ground-attack aircraft for close air support

- 23rd Tactical Fighter Wing – provided close air support for allied forces with A-10 Warthogs

- 26th Air Defense Squadron NORAD – provided air support for F-15 Eagles

- 33rd Tactical Fighter Wing – provided air superiority cover for allied forces with F-15 Eagles

- 437th Military Airlift Wing – provided airlift support with C-141 Starlifters

- 16th Special Operations Wing – flew AC-130H Spectre gunships

- 317th Military Airlift Wing – provided airlift support with C-130 Hercules from Pope AFB / Fort Bragg, NC complex to Grenada

- 63d Military Airlift Wing – Provided airlift support with C-141 Starlifter aircraft in the air landing of Airborne troops, 63rd Security Police Squadron provided airfield security support – (Norton AFB CA)

- 443rd Military Airlift Wing, 443rd Security Police Squadron (Altus AFB, OK) – provided a 44-man Airbase Ground Defense flight (Oct–Nov 1983)

- 19th Air Refueling Wing – provided aerial refueling support for all other aircraft

- 507th Tactical Air Control Wing (elements of the 21st TASS at Shaw AFB, SC and Detachment 1, Fort Bragg, NC) – provided Tactical Air Control Parties (TACPs) in support of the 82nd Airborne Division

- 552nd Air Control Wing, providing air control support with E-3 Sentry AWACS aircraft

- 62nd Security Police Group (Provisional) Multi Squadron Law Enforcement & Security Forces – Prisoner detaining and transport attached to 82nd Airborne

- 60th Military Airlift Wing's 60th Security Police Squadron (Travis AFB, CA) provided airfield security in Grenada as well as Barbados.

U.S. Navy

Two formations of U.S. warships took part in the invasion. USS Independence (CVA-62) carrier battle group; and Marine Amphibious Readiness Group, flagship USS Guam (LPH-9), USS Barnstable County (LST-1197), USS Manitowoc (LST-1180), USS Fort Snelling (LSD-30), and USS Trenton (LPD-14). Carrier Group Four was allocated the designation Task Group 20.5 for the operation.

| Surface warships | Carrier Air Wing Six (CVW-6) squadrons embarked aboard flagship Independence | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| USS Independence (CV-62) | Fighter Squadron 14 (VF-14): 13 F-14A | Carrier Airborne Early Warning Squadron 122 (VAW-122): 4 E-2C | |

| USS Coontz (DDG-40) | Fighter Squadron 32 (VF-32): 14 F-14A | Electronic Attack Squadron 131 (VAQ-131): 4 EA-6B | |

| USS Moosbrugger (DD-980) | Attack Squadron 176 (VA-176): 16 A-6E/KA-6D | Helicopter Antisubmarine Squadron (15 HS-15): 6 SH-3H | |

| USS Caron (DD-970) | Attack Squadron 87 (VA-87): 12 A-7E | Sea Control Squadron 28 (VS-28): 10 S-3A | |

| USS Clifton Sprague (FFG-16) | Attack Squadron 15 (VA-15): 12 A-7E | COD: 1 C-1A | |

| USS Suribachi (AE-21) | ---- | ---- | |

In addition, the following ships supported naval operations:

USS Kidd (DDG-993), USS Aquila (PHM-4), USS Aubrey Fitch (FFG-34), USS Briscoe (DD-977), USS Portsmouth (SSN-707), USS Recovery (ARS-43), USS Saipan (LHA-2), USS Sampson (DDG-10), USS Samuel Eliot Morison (FFG-13), USS John L. Hall (FFG-32), USS Silversides (SSN-679), USS Taurus (PHM-3), USNS Neosho (T-AO-143), USS Caloosahatchee (AO-98) and USS Richmond K. Turner (CG-20).

U.S. Coast Guard

USCGC Cape York (WPB - 95332)

In popular culture

The 1986 film Heartbreak Ridge by Clint Eastwood follows a group of Marines preparing for and participating in the invasion.

In the 2013 movie The Wolf of Wall Street, the invasion of Granada is used as a metaphor for a court case that is impossible to lose.

Notes

- ↑ Clarke, Jeffrey J. Operation Urgent Fury: The Invasion of Grenada, October 1983 (PDF). United States Army.

- 1 2 "Operation Urgent Fury"' GlobalSecurity.org

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Cole, Ronald (1997). "Operation Urgent Fury: The Planning and Execution of Joint Operations in Grenada" (PDF). Retrieved 9 November 2006.

- ↑ "Medals Outnumber G.I.'S In Grenada Assault". The New York Times. 30 March 1984.

- ↑ "PBS.org:The Invasion of Grenada".

- ↑ "Soldiers During the Invasion of Grenada". CardCow Vintage Postcards.

- ↑ "Caribbean Islands – A Regional Security System". country-data.com.

- ↑ Charles Moore, Margaret Thatcher: At her Zenith (2016) p. 130.

- 1 2 "United Nations General Assembly resolution 38/7". United Nations. 2 November 1983. Retrieved 5 March 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Magnuson, Ed (21 November 1983). "Getting Back to Normal". Time.

- ↑ Associated Press report in 2012, printed in Fox News

- ↑ Steven F. Hayward. The Age of Reagan: The Conservative Counterrevolution: 1980–1989. Crown Forum. ISBN 1-4000-5357-9.

- ↑ Tessler, Ray (19 August 1991). "Gulf War Medals Stir Up Old Resentment". Los Angeles Times. p. 2. Retrieved 30 June 2013.

- ↑ "Overdecorated". Time. 9 April 1984.

- ↑ Peter Collier, David Horowitz (January 1987). "Another "Low Dishonest Decade" on the Left". Commentary.

- ↑ Gailey, Phil; Warren Weaver Jr. (26 March 1983). "Grenada". New York Times. Retrieved 11 March 2008.

- 1 2 "St. Vincent's Prime Minister to officiate at renaming of Grenada international airport". Caribbean Net News newspaper. 26 May 2009.

- 1 2 "BISHOP'S HONOUR: Grenada airport renamed after ex-PM". Caribbean News Agency (CANA). 30 May 2009. Archived from the original on 12 June 2009.

- 1 2 Sir Paul Scoon, G-G of Grenada, at 2:36 on YouTube

- 1 2 Martin, Douglas (2013-09-09). "Paul Scoon, Who Invited Grenada Invaders, Dies at 78". The New York Times.

- ↑ Thatcher, Margaret (Jan 2011). The Downing Street Year. London: HarperCollins. p. 841. ISBN 9780062029102.

- ↑ "United Nations General Assembly resolution 38/7". United Nations. 2 November 1983. Archived from the original on 19 November 2000.

- ↑ "Assembly calls for cessation of "armed intervention" in Grenada". UN Chronicle. 1984.

- ↑ Carter, Gercine (26 September 2010). "Ex-airport boss recalls Cubana crash". Nation Newspaper. Archived from the original on 24 January 2012. Retrieved 16 October 2011.

- ↑ Huchthausen, Peter (2004). America's Splendid Little Wars: A Short History of U.S. Engagements from the Fall of Saigon to Baghdad. New York: Penguin. p. 69. ISBN 0-14-200465-0.

- 1 2 3 Grenada 1983 by Lee E. Russell and M. Albert Mendez, 1985 Osprey Publishing Ltd., ISBN 0-85045-583-9 pp. 28–48.

- 1 2 Dominguez, Jorge. To Make a World Safe for Revolution: Cuba's Foreign Policy. Center for International Affairs. pp. 154–253. ISBN 978-0674893252.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Domínguez, Jorge I. (1989). To Make a World Safe for Revolution: Cuba's Foreign Policy. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-89325-5. pp. 168–69

- ↑ Woodward, Bob (1987). Veil: The Secret Wars of the CIA 1981–1987. Simon & Schuster.

- ↑ Leckie, Robert (1998). The Wars of America. Castle Books.

- 1 2 3 4 Stuart, Richard W. (2008). Operation Urgent Fury: The Invasion of Grenada, October 1983 (PDF). U.S. Army.

- 1 2 3 4 "Turning the Tide: Operation Urgent Fury". Combat Reform. Retrieved 6 April 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 Kreisher, Otto. "Operation URGENT FURY – Grenada". Marine Corps Association & Foundation.

- ↑ Kreisher, Otto (October 2003). "Operation URGENT FURY – Grenada". Marine Corps Association and Foundation. Retrieved 28 April 2016.

- ↑ Fortitudine: Newsletter of the Marine Corps Historical Program, Volumes 15–18. Tommell, Anthony Wayne. History and Museums Division, U.S. Marine Corps, 1985.

- ↑ Nightline – 25 Oct 1983 – ABC – TV news: Vanderbilt Television News Archive

- ↑ Television News Archive: Nightline

- ↑ United Nations Yearbook, Volume 37, 1983, Department of Public Information, United Nations, New York

- ↑ Zunes, Stephen (October 2003). "The U.S. Invasion of Grenada: A Twenty Year Retrospective". Foreign Policy in Focus.

- ↑ "Spartacus Educational".

- ↑ "United Nations Security Council vetoes". United Nations. 28 October 1983. Retrieved 5 March 2016.

- ↑ "Reagan: Vote loss in U.N. 'didn't upset my breakfast'". The Spokesman-Review. 4 November 1983. Retrieved 30 June 2013.

- ↑ "Thatcher letter to Reagan ("deeply disturbed" at U.S. plans) [memoirs extract]". Margaret Thatcher Foundation. 25 October 1983. Retrieved 25 October 2008.

- ↑ Thatcher, Margaret (1993) The Downing Street Years p. 331.

- ↑ John Campbell, Margaret Thatcher Volume Two: The Iron Lady (2011) pp. 273–79.

- ↑ Gary Williams, "‘A Matter of Regret’: Britain, the 1983 Grenada Crisis, and the Special Relationship." Twentieth Century British History 12#2 (2001): 208–30.

- ↑ "Prime Minister Speech at Airport Renaming Ceremony". Grenadian Connection. 30 May 2009.

- ↑ For Cubans – "The Nation Newspaper", 13 October 2008

- 1 2 Spector, Ronald (1987). "U.S. Marines in Grenada 1983" (PDF). p. 6.

Primary sources

- Grenada Documents, an Overview & Selection, DOD & State Dept, Sept 1984, 813 pages.

- Grenada, A Preliminary Report, DOD & State

- Joint Overview, Operation Urgent Fury, 1 May 1985, 87 pages

Further reading

- Adkin, Mark (1989). Urgent Fury: The Battle for Grenada: The Truth Behind the Largest U.S. Military Operation Since Vietnam. Lexington Books. ISBN 0-669-20717-9.

- Brands, H. W., Jr. (1987). "Decisions on American Armed Intervention: Lebanon, Dominican Republic, and Grenada". Political Science Quarterly. 102 (4): 607–624. JSTOR 2151304.

- Cole, Ronald H. (1997). Operation Urgent Fury: The Planning and Execution of Joint Operations in Grenada, 12 October - 2 November 1983 (PDF). Washington, D.C. Official Pentagon study.

- Gilmore, William C. (1984). The Grenada Intervention: Analysis and Documentation. New York: Facts on File. ISBN 0-87196-920-3.

- Moore, Charles. Margaret Thatcher: At her Zenith in London, Washington and Moscow (2016) pp. 117-35.

- Payne, Anthony. "The Grenada crisis in British politics." The Round Table 73.292 (1984): 403-410. online

- Russell, Lee (1985). Grenada 1983. London: Osprey. ISBN 0-85045-583-9., A military history.

- Williams, Gary. US-Grenada Relations: Revolution and Intervention in the Backyard (Macmillan, 2007).

External links

- Invasion of Grenada and Its Political Repercussions from the Dean Peter Krogh Foreign Affairs Digital Archives

- Operation: Urgent Fury, Grenada

- The 1983 Invasion of Grenada, Operation: Urgent Fury

- "Grenada, Operation Urgent Fury (23 October – 21 November 1983)"—Naval History & Heritage Command, U.S. Navy

- Grenada—a 1984 comic book about the invasion written by the CIA.