United Nations Convention against Corruption

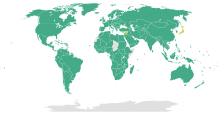

Signatories (orange) and Ratifications (green) of the treaty. | |

| Drafted | 31 October 2003 |

|---|---|

| Signed | 9 December 2003 |

| Location | Mérida and New York |

| Effective | 14 December 2005 |

| Condition | 30 ratifications |

| Signatories | 140 |

| Parties | 181 |

| Depositary | Secretary-General of the United Nations |

| Languages | Arabic, Chinese, English, French, Russian and Spanish |

The United Nations Convention against Corruption (UNCAC) is a multilateral treaty negotiated by member states of the United Nations (UN) and promoted by the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). It is one of several legally binding international anti-corruption agreements. UNCAC requires state parties to the treaty to implement several anti-corruption measures that focus on five main areas: prevention, law enforcement, international cooperation, asset recovery, and technical assistance and information exchange.[1]

UNCAC's goal is to reduce various types of corruption that can occur across country borders, such as trading in influence and abuse of power, as well as corruption in the private sector, such as embezzlement and money laundering. Another goal of the UNCAC is to strengthen international law enforcement and judicial cooperation between countries by providing effective legal mechanisms for international asset recovery. The Conference of the States Parties to the UNCAC provides participating countries with resources and assistance to improve implementation of the obligations set forth by the Convention.[1]

Signatures, ratifications and entry into force

UNCAC was adopted by the United Nations General Assembly on 31 October 2003 by Resolution 58/4. It was opened for signature in Mérida, Yucatán, Mexico, from 9–11 December 2003 and thereafter at UN headquarters in New York City. It was signed by 140 countries. As of July 2017, there are 182 parties, which includes 178 UN member states, the Cook Islands, the Holy See, the State of Palestine, and the European Union.[2]

As of July 2017, the 15 UN member states that have not ratified the convention are (asterisk indicates that the state has signed the convention):

Background

UNCAC is the most recent of a long series of developments in which experts and politicians have recognized the far-reaching impact of corruption and economic crime that undermine the value of democracy, sustainable development, and rule of law.[3] They have also recognized the need to develop effective measures against corruption at both the domestic and international levels. International action against corruption has progressed from general consideration and declarative statements to legally binding agreements. While at the beginning of the discussion measures were focused relatively narrowly on specific crimes, above all bribery, the understanding of corruption has become broader and so have the measures against it. UNCAC's comprehensive approach and the mandatory character of many of its provisions give proof of this development. UNCAC deals with forms of corruption that had not been covered by many of the earlier international instruments, such as trading in influence, abuse of function, and various types of corruption in the private sector. A further significant development was the inclusion of a specific chapter dealing with the recovery of stolen assets, a major concern for countries that pursue the assets of former leaders and other officials accused or found to have engaged in corruption.

Other major anti-corruption conventions, such as the Inter-American Convention against Corruption, the OECD Anti-Bribery Convention, and the African Union Convention on Preventing and Combating Corruption, are restricted to either certain regions of the world or certain manifestations of corruption.

Conference of the States Parties

Pursuant to article 63 of UNCAC, a Conference of the States Parties (CoSP) to UNCAC was established to improve the capacity of and cooperation between States Parties to achieve the objectives set forth in UNCAC, and to promote and review its implementation. UNODC acts as the secretariat to the CoSP.

At its different sessions, besides regularly calling States Parties and signatories to adapt their laws and regulations to bring them into conformity with the provisions of UNCAC[4] [5] the CoSP has adopted resolutions and has mandated UNODC to implement them, including through the development of technical assistance projects.[6]

The CoSP has established a number of subsidiary bodies to further the implementation of specific aspects of UNCAC. The Implementation Review Group,[7] which focuses on the implementation review mechanism and technical assistance, the Working Group on Asset Recovery, the Working Group on Prevention,[8] as well as expert group meetings on international cooperation[9] meet regularly in the intersessional period.

The first session of the CoSP took place on 10–14 December 2006 at the Dead Sea, Jordan. In its resolution 1/1, States Parties agreed that it was necessary to establish an appropriate and effective mechanism to assist in the review of the implementation of UNCAC. An inter-governmental working group was established to start working on the design of such a mechanism.[10] Two other working groups were set up to promote coordination of activities related to technical assistance and asset recovery, respectively.

The second CoSP was held in Bali, Indonesia, from 28 January to 1 February 2008. As to the mechanism for the review of implementation, the States Parties decided to take into account a balanced geographical approach, to avoid any adversarial or punitive elements, to establish clear guidelines for every aspect of the mechanism and to promote universal adherence to UNCAC and the constructive collaboration in preventive measures, asset recovery, international cooperation and other areas. The CoSP also requested donors and receiving countries to strengthen coordination and enhance technical assistance for the implementation of UNCAC, and dealt with the issue of bribery of officials of public international organizations.[11]

The third session of the CoSP took place in Doha, Qatar, from 9 to 13 November 2009. The CoSP adopted the landmark Resolution 3/1 on the review of the implementation of UNCAC, containing the terms of reference of the Implementation Review Mechanism(IRM).[12] In view of the establishment of the IRM, and considering that the identification of needs and the delivery of technical assistance to facilitate the successful and consistent implementation of UNCAC are at the core of the mechanism, the CoSP decided to abolish the Working Group on Technical Assistance and to fold its mandate into the work of the Implementation Review Group.[13] At its third session, for the first time, the CoSP also adopted a resolution on preventive measures, in which it established the Open-Ended Intergovernmental Working Group on Prevention to further explore good practices in this field.[14] The CoSP was preceded and accompanied by numerous side events, such as the last Global Forum for Fighting Corruption and Safeguarding Integrity (in cooperation with businesses) and a Youth Forum.[15]

The fourth session of the CoSP took place in Marrakech, Morocco, from 24 to 28 October 2011. The Conference considered the progress made in the IRM and recognized the importance of addressing technical assistance needs in the Review Mechanism.[7] It also reiterated its support for the Working Groups on Asset Recovery[16] and Prevention[17] and established Open-Ended Intergovernmental Expert Group Meetings on International Cooperation to advise and assist the CoSP with respect to extradition and mutual legal assistance.[9] In addition to its main agenda, the CoSP hosted 19 side events, bringing together governments and different parts of society, such as the private sector, parliamentarians, anti-corruption authorities and civil society organizations.

The next sessions of the CoSP will take place in Panama in 2013,[18] the Russian Federation in 2015[19] and Austria in 2017.[20]

Measures and provisions

UNCAC covers five main areas: preventive measures, criminalization and law enforcement, international cooperation, asset recovery, and technical assistance and information exchange. It includes both mandatory and non-mandatory provisions.

General provisions (Chapter I, Articles 1–4)

The opening Articles of UNCAC include a statement of purpose (Article1), which covers both the promotion of integrity and accountability within each country and the support of international cooperation and technical assistance between States Parties. They also include definitions of critical terms used in the instrument. Some of these are similar to those used in other instruments, and in particular the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime (UNTOC), but those defining "public official", "foreign public official", and " official of a public international organization" are new and are important for determining the scope of application of UNCAC in these areas. UNCAC does not provide for a definition of corruption. In accordance with Article 2 of the UN Charter, Article 4 of UNCAC provides for the protection of national sovereignty of the States Parties.,[21][22]

Preventive measures (Chapter II, Articles 5–14)

UNCAC recognizes the importance of the prevention in both the public and private sectors. Chapter II includes preventive policies, such as the establishment of anti-corruption bodies and enhanced transparency in the financing of election campaigns and political parties. Anti-corruption bodies should implement anti-corruption policies, disseminate knowledge and must be independent, adequately resourced and have properly trained staff.

Countries that sign the convention must assure safeguards their public services are subject to safeguards that promote efficiency, transparency and recruitment based on merit. Once recruited, public servants should be bound by codes of conduct, requirements for financial and other disclosures, and appropriate disciplinary measures. Transparency and accountability in the management of public finances must also be promoted, and specific requirements are established for the prevention of corruption in the particularly critical areas of the public sector, such as the judiciary and public procurement. Preventing corruption also requires an effort from all members of society at large. For these reasons, UNCAC calls on countries to promote actively the involvement of civil society, and to raise public awareness of corruption and what can be done about it. The requirements made for the public sector also apply to the private sector – it too is expected to adopt transparent procedures and codes of conduct.[23]

Criminalization and law enforcement (Chapter III, Articles 15–44)

Chapter III calls for parties to establish or maintain a series of specific criminal offences including not only long-established crimes such as bribery and embezzlement, but also conducts not previously criminalized in many states, such as trading in influence and other abuses of official functions. The broad range of ways in which corruption has manifested itself in different countries and the novelty of some of the offences pose serious legislative and constitutional challenges, a fact reflected in the decision of the Ad Hoc Committee to make some of the provisions either optional ("…shall consider adopting…") or subject to domestic constitutional or other fundamental requirements ("…subject to its constitution and the fundamental principles of its legal system…").[24] Specific acts that parties must criminalize include

- active bribery of a national, international or foreign public officials

- passive bribery of a national public official

- embezzlement of public funds

Other mandatory crimes include obstruction of justice, and the concealment, conversion or transfer of criminal proceeds (money laundering). Sanctions extend to those who participate in and may extend to those who attempt to commit corruption offences.[25] UNCAC thus goes beyond previous instruments of this kind that request parties to criminalize only basic forms of corruption. Parties are encouraged – but not required – to criminalize, inter alia, passive bribery of foreign and international public officials, trading in influence, abuse of function, illicit enrichment, private sector bribery and embezzlement, and the concealment of illicit assets.

Furthermore, parties are required to simplify rules pertaining to evidence of corrupt behavior by, inter alia, ensuring that obstacles that may arise from the application of bank secrecy laws are overcome. This is especially important, as corrupt acts are frequently very difficult to prove in court. Particularly important is also the introduction of the liability of legal persons. In the area of law enforcement, UNCAC calls for better cooperation between national and international bodies and with civil society. There is a provision for the protection of witnesses, victims, expert witnesses and whistle blowers to ensure that law enforcement is truly effective.

Russia ratified the convention in 2006, but failed to include article 20, which criminalizes “illicit enrichment.” In March 2013, the Communist Party of the Russian Federation submitted a petition with 115,000 signatures to the State Duma in favour of doing so.[26] In 2015, however, no such law was yet in effect in Russia.

International cooperation (Chapter IV, Articles 43–49)

Under Chapter IV of UNCAC, States Parties are obliged to assist one another in every aspect of the fight against corruption, including prevention, investigation, and the prosecution of offenders. Cooperation takes the form of extradition, mutual legal assistance, transfer of sentences persons and criminal proceedings, and law enforcement cooperation. Cooperation in civil and administrative matters is also encouraged. Based on Chapter IV, UNCAC itself can be used as a basis for extradition, mutual legal assistance and law enforcement with respect to corruption-related offences. "Dual criminality", which is a requirement that the relevant offence shall be criminalized in both the requesting and requested country, is considered fulfilled irrespective of whether the same terminology or category of offense is used in both jurisdictions. In case of a request for assistance involving non-coercive measures, States Parties are required to provide assistance even when dual criminality is absent subject only to the basic concepts of their legal systems. Chapter IV also contains other innovative provisions designed to facilitate international cooperation. For example, States Parties that use UNCAC as a basis for extradition shall not consider corruption-related offences as political ones; assistance can also be provided in relation to offences for which legal persons can be held responsible; and bank secrecy cannot be cited as a ground to refuse a request for assistance. In order to ensure speedy and efficient cooperation, each State Party is required to designate a central authority responsible for receiving MLA requests. Overall, Chapter IV provides a broad and flexible platform for international cooperation. However, its provisions do not exhaust all international cooperation issues covered by UNCAC, thus the purposes of UNCAC and provisions of other chapters also need to be taken into consideration.[27]

Asset recovery (Chapter V, Articles 51–59)

The agreement on asset recovery is considered a major breakthrough and many observers claim that it is one of the reasons why so many developing countries have signed UNCAC.[28] Asset recovery is indeed a very important issue for many developing countries where high-level corruption has plundered the national wealth. Reaching an agreement on this Chapter involved intensive negotiations, as the legitimate interests of countries wishing to recover illicit assets had to be reconciled with the legal and procedural safeguards of the countries from which assistance will be sought.[29] Generally, in the course of the negotiations, countries seeking to recover assets sought to establish presumptions that would make clear their ownership of the assets and give priority for return over other means of disposal. Countries from which the return was likely to be sought, on the other hand, had concerns about the language that might have compromised basic human rights and procedural protections associated with criminal liability and the freezing, seizure, forfeiture and return of such assets.

Chapter V of UNCAC establishes asset recovery as a "fundamental principle" of the Convention. The provisions on asset recovery lay a framework, in both civil and criminal law, for tracing, freezing, forfeiting and returning funds obtained through corrupt activities. The requesting state will in most cases receive the recovered funds as long as it can prove ownership. In some cases, the funds may be returned directly to individual victims.

If no other arrangement is in place, States Parties may use the Convention itself as a legal basis. Article 54(1)(a) of UNCAC provides that: "Each State Party (shall)... take such measures as may be necessary to permit its competent authorities to give effect to an order of confiscation issued by a court of another state party" Indeed, Article 54(2)(a) of UNCAC also provides for the provisional freezing or seizing of property where there are sufficient grounds for taking such actions in advance of a formal request being received.[30]

Recognizing that recovering assets once transferred and concealed is an exceedingly costly, complex and an all-too-often unsuccessful process, this Chapter also incorporates elements intended to prevent illicit transfers and generate records that can be used where illicit transfers eventually have to be traced, frozen, seized and confiscated (Article 52). The identification of experts who can assist developing countries in this process is also included as a form of technical assistance (Article 60(5)).

Technical assistance and information exchange (Chapter VI, Articles 60–62)

Chapter VI of UNCAC is dedicated to technical assistance, meaning support offered to developing and transition countries in the implementation of UNCAC. The provisions cover training, material and human resources, research, and information sharing. UNCAC also calls for cooperation through international and regional organizations (many of which already have established anti-corruption programmes), research efforts, and the contribution of financial resources both directly to developing countries and countries with economies in transition, and to the UNODC.

Mechanisms for implementation (Chapter VII, Articles 63–64)

Chapter VII deals with international implementation through the CoSP and the UN Secretariat.

Final provisions (Chapter VIII, Articles 65 – 71)

The final provisions are similar to those found in other UN treaties. Key provisions ensure that UNCAC requirements are to be interpreted as minimum standards, which States Parties are free to exceed with measures "more strict or severe" than those set out in specific provisions; and the two Articles governing signature, ratification and the coming into force of the Convention.[24]

Implementation of the UNCAC and monitoring mechanism

In accordance with Article 63(7) of UNCAC, "the Conference shall establish, if it deems necessary, any appropriate mechanism or body to assist in the effective implementation of the Convention".[31] At its first session, the CoSP established an open-ended intergovernmental expert group to make recommendations to the Conference on the appropriate mechanism. A voluntary "Pilot Review Programme", which was limited in scope, was initiated to offer adequate opportunity to test possible methods to review the implementation of UNCAC, with the overall objective to evaluate efficiency and effectiveness of the tested mechanism(s) and to provide to the CoSP information on lessons learnt and experience acquired, thus enabling the CoSP to make informed decisions on the establishment of an appropriate mechanism for reviewing the implementation of UNCAC. The CoSP at its third session, held in Doha in November 2009, adopted Resolution 3/1 on the review of the implementation of the Convention, containing the terms of reference of an Implementation Review Mechanism (IRM). It established a review mechanism aimed at assisting countries to meet the objectives of UNCAC through a peer review process. The IRM is intended to further enhance the potential of the UNCAC, by providing the means for countries to assess their level of implementation through the use of a comprehensive self-assessment checklist, the identification of potential gaps and the development of action plans to strengthen the implementation of UNCAC domestically. UNODC serves as the secretariat to the review mechanism.[12]

The Terms of Reference of the IRM specify that each review phase is composed of two review cycles of five years. The first review cycle covers chapters III (criminalization and law enforcement) and IV (international cooperation) of UNCAC. The second review cycle, which will start in 2015, covers chapters II (preventive measures) and V (asset recovery). All States parties must undergo the review within each cycle. The selection of the reviewing States parties is carried out by drawing of lots. Each State party is reviewed by two other States parties, with the active involvement of the State Party under review. At least one of the reviewing States is from the regional group of the State party under review.[12]

An initial desk review is based on the responses of each State to the IT-based comprehensive self-assessment checklist. States parties under review are encouraged to conduct broad consultations including all relevant stakeholders when preparing their responses. Active dialogue between the country under review and the reviewers is a key component of the process. Country visits or joint meetings are held when agreed by the State party under review. A country review report is prepared and agreed to by the country under review and may be made public. The executive summary of this report is an official document of the United Nations.

As of 4 October 2012, 157 countries are involved in the Review Mechanism either as countries under review or as reviewing countries.

UNCAC Coalition of Civil Society Organisations

The UNCAC Coalition, established in 2006, is a network of some 310 civil society organizations (CSOs) in over 100 countries, committed to promoting the ratification, implementation and monitoring of UNCAC. It aims to mobilize broad civil society support for UNCAC and to facilitate strong civil society action at national, regional and international levels in support of UNCAC. The Coalition is open to all organizations and individuals committed to these goals. The breadth of UNCAC means that its framework is relevant for a wide range of CSOs, including groups working in the areas of human rights, labour rights, governance, economic development, environment and private sector accountability.

Challenges

Ratification of UNCAC, while essential, is only the first step. Fully implementing its provisions presents significant challenges for the international community as well as individual States parties, particularly in relation to the innovative areas of UNCAC. For this reason, countries have often needed policy guidance and technical assistance to ensure the effective implementation of UNCAC. The results of the first years of IRM have shown that many developing countries have identified technical assistance needs. The provision of technical assistance, as foreseen in UNCAC, is crucial to ensure the full and effective incorporation of the provisions of UNCAC into domestic legal systems and, above all, into the reality of daily life.[32]

See also

- Convention against Transnational Organized Crime

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime

- International asset recovery

- Transparency International

- United Nations Global Compact

- International Anti-Corruption Day

References

- 1 2 "UNODC and Corruption". unodc.org. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Retrieved 17 February 2017.

- ↑ Signatories to the UNCAC

- ↑ The Preamble of the United Nations Convention against Corruption

- ↑ Resolutions 1/3 of the Conference of the States Parties to the United Nations Convention against Corruption

- ↑ 2/4 of the Conference of the States Parties to the United Nations Convention against Corruption

- ↑ Resolutions of the Conference of the States Parties to the United Nations Convention against Corruption

- 1 2 Resolution 4/1 of the Conference of the States Parties to the United Nations Convention against Corruption

- ↑ Resolution 4/3 and 4/4 of the Conference of the States Parties to the United Nations Convention against Corruption

- 1 2 Resolution 4/2 of the Conference of the States Parties to the United Nations Convention against Corruption

- ↑ Resolution 1/1 of the Conference of the States Parties to the United Nations Convention against Corruption

- ↑ Second Session of the CoSP

- 1 2 3 Resolution 3/1 of the Conference of the States Parties to the United Nations Convention against Corruption

- ↑ Resolution 3/4 of the Conference of the States Parties to the United Nations Convention against Corruption

- ↑ Resolution 3/2 of the Conference of the States Parties to the United Nations Convention against Corruption

- ↑ Third Session of the CoSP

- ↑ Resolution 4/4 of the Conference of the States Parties to the United Nations Convention against Corruption

- ↑ Resolution 4/3 of the Conference of the States Parties to the United Nations Convention against Corruption

- ↑ Decision 3/1 of the Conference of the States Parties to the United Nations Convention against Corruption

- ↑ Decision 4/1 of the Conference of the States Parties to the United Nations Convention against Corruption

- ↑ Decision 4/2 of the Conference of the States Parties to the United Nations Convention against Corruption

- ↑ UN Charter

- ↑ United Nations Convention against Corruption (Full text)

- ↑ GTZ document on highlights of the UNCAC

- 1 2 UNODC Anti-Corruption Toolkit Archived 18 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ U4 The United Nations Convention against Corruption A Primer for Development Practitioners Archived 19 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Communists Get 115K Signatures for Anti-Graft Convention, The Moscow Times, 21 March 2013.

- ↑ Highlights of the UN Convention against Corruption

- ↑ U4 Introduction to the UN Convention against Corruption Archived 19 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ GTZ article on Asset Recovery

- ↑ Asset recovery

- ↑ http://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/treaties/CAC/CAC-COSP-session1-resolutions.html

- ↑ http://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/treaties/CAC/country-profile/index.html

External links

- ratifications

- United Nations Convention against Corruption website

- UNCAC Coalition of Civil Society Organisations

- UNCAC Theme page at the Anti-Corruption Resource Centre

- Transparency International

- Highlights on the UN Convention against Corruption by GTZ