United Kingdom enterprise law

United Kingdom enterprise law concerns the ownership, regulation and potentially competition in the provision of public services, private or mutual companies in the United Kingdom.

History

- Port of London Act 1908

- National Insurance Act 1911

- Railways Act 1921

- Bank of England Act 1946

- National Health Service Act 1946

- Transport Act 1947

- Electricity Act 1947

- Gas Act 1986

General enterprise law

Corporate governance

- Companies Act 2006 ss 21, 112, 168 and 284, company constitutions, amendment, voting rights and removal of directors

- Model Articles, Sch 3, paras 3 and 34, model articles for public companies

- Companies Act 2006 ss 170-177, 260-263 and 419 (directors’ duties, derivative claims, report)

- Pensions Act 2004 ss 241-243, right of pension beneficiaries to nominate pension trustees

- Charities Act 2006

Labour rights

- Autoclenz Ltd v Belcher [2011] UKSC 41, minimum wage and working time claims

- Trade Union and Labour Relations (Consolidation) Act 1992 ss 179, 219, 224, 244 (collective agreements not legally binding, immunity from damages for collective action in contemplation or furtherance of a trade dispute, no secondary action, meaning of a trade dispute)

- ECHR article 11

- RMT v United Kingdom [2014] ECHR 366, secondary action

- Health and Safety Executive

Competition and consumers

- TFEU arts 101 and 102

- Competition Act 1998 ss 2-3, 18-19 and Sch 3, prohibition of abuse of a dominant position and collusion

- TFEU arts 106(2) and 345, state aid and neutrality to public ownership

- Albany International BV v Stichting Bedrijfspensioenfonds Textielindustrie (1999) C-67/96

- Public procurement

- State aid

- Consumer Rights Act 2015

- Sale of Goods Act 1979

- Consumer cooperative

- Consumer Protection Act 1987

- Environmental Protection Act 1990

Insolvency

- Insolvency Act 1986 ss 175-176A and Sch 6, preferential rights in insolvency for employees and pensions

- Re Spectrum Plus Ltd [2005] UKHL 41, interpretation of a ‘floating charge’

- Insolvency Act 1986 Sch B1, paras 3, 14, 22 and 36, governance in administering insolvent companies

Administrative law

- Parliament and local government

- Municipal Corporations Act 1882, allowed establishment of elected councils

- Civil service and bureaucracy

- Courts in England and Wales

- Judicial review

- Deregulation and Contracting Out Act 1994

- Legislative and Regulatory Reform Act 2006

- Regulatory Reform Act 2001

Specific enterprises

Education

- UDHR 1948 art 26

- European Social Charter 1961 arts 7, 10 and 17

- ECHR 1950 Protocol 1, article 2

- Belgian Linguistic case (No 2) (1968) 1 EHRR 252

- CFREU 2000 article 14.

- Further and Higher Education Act 1992 ss 62-69, 81, and 89 (funding councils)

- Education Reform Act 1988 ss 124A, 128, Schs 7 and 7A, para 3 (uni formation, dissolution, governance)

- King’s College London Act 1997 s 15 (yet to be ‘appointed’), cf The Charter and Statutes, art 1

- London School of Economics, Memorandum and Articles of Association (2006) art 10.5

- Cambridge University Act 1856 ss 5 and 12, cf Statute A, chs I-IV

- Oxford University Act 1854 ss 16 and 21, cf Statute IV and VI, Council Regulations 13 of 2002, regs 4-10

- Clark v University of Lincolnshire and Humberside [2000] EWCA Civ 129 (contractual claim)

- R (Persaud) v University of Cambridge [2001] EWCA Civ 534 (judicial review)

- Higher Education Act 2004 ss 23-24 and 31-39 (tuition fees and plans)

- Higher Education (Higher Amount) Regulations 2010 regs 4-5A (limit on undergraduate fees)

- R (Bidar) v London Borough of Ealing (2005) C-209/03

- Royal Charter

- Universities Tests Act 1871, nonconformist entry to university

- University of London Act 1898

- Education Act 1962, grants, and Robbins Report (1963)

- Teaching and Higher Education Act 1998, fees of up to £1000, General Teaching Councils and code

- Higher Education Act 2004 up to £3000 in fees

- Schools

- Education Act 1833

- Public Schools Act 1868, following the Clarendon Commission removed charity schools from government or education department oversight, and now the main UK private schools

- Elementary Education Act 1870, five to twelve-year-olds, school boards providing universal primary education

- Education Act 1902, abolished 2,568 school boards and instituted 328 local education authorities in their place, following the Cockerton judgment

- Education (Provision of Meals) Act 1906, introduced free school meals

- Education (Administrative Provisions) Act 1907, medical services

- Education Act 1918, school leaving age raised to fourteen years, maximum class size of thirty

- Education Act 1944, attempted foundation of tripartite secondary school system, every child got free school meals, until 1949 when it was 2.5 pence

- Education Reform Act 1988, schools could remove themselves from LEA oversight and become "grant-maintained" by central government, headteachers getting financial control, academic tenure abolished, national curriculum with key stages, league tables

- Education Act 1996, teacher training, and opt out from student union

- School Standards and Framework Act 1998, thirty infant pupil class size limit, replaced "grant-maintained schools" with "foundation status" meaning money is channelled from central government through the LEA, restrictions on selection

- Learning and Skills Act 2000 and Education Act 2002 and Academies Act 2010, allowed for academies outside national curriculum and autonomy over teacher pay

- Education Act 2005, Ofsted inspections

- Education and Inspections Act 2006, trust schools

- Libraries

Health

- UDHR 1948 art 25

- European Social Charter 1961 arts 11 and 13

- ECHR 1950 arts 2, 3 and 8

- CFREU 2000 art 35.

- Department of Health, NHS Constitution for England (27 July 2015) arts 1, 3a and 4a

- National Health Service Act 2006 ss 1, 1H-I, Sch 1A, Sch 7 paras 3-9 (cf HSCA 2012 ss 1-10, 62, Sch 2)

- National Health Service (Clinical Commissioning Groups) Regulations 2012 regs 11-12

- Health and Social Care Act 2012 ss 75, 115-121 and 165 (competition, pricing, private work)

- NHS (Procurement, Patient Choice and Competition) (No 2) Regulations 2013 regs 2-11

- National Health Service (Private Finance) Act 1997 (c 56) s 1 (right to borrow with Minister approval)

- NHSA 2006 ss 1A-C and 3

- R (B) v Cambridge Health Authority [1995] EWCA Civ 43 (discretion to refuse treatment)

- R (Coughlan) v North and East Devon HA [1999] EWCA Civ 1871 (legitimate expectations, like contract)

- R (Ann Marie Rogers) v Swindon Primary Care Trust [2006] EWCA Civ 392 (exceptionality and resources)

- R (Watts) v Bedford Primary Care Trust (2006) C-372/04 (limited right to reimbursement)

- National Health Service Act 2006 ss 6BB and 175 (reimbursement and charges)

- National Health Service (Charges to Overseas Visitors) Regulations 2015 regs 3-9

- N v United Kingdom [2008] ECHR 453

- Bethlem Royal Hospital

- National Insurance Act 1911

- National Health Service Act 1946

- National Health Service Act 1977 (c 49)

- National Health Service and Community Care Act 1990 (c 19)

- National Health Service (Primary Care) Act 1997 (c 46)

- National Health Service Act 1966 (c 8) section 10, on GP remuneration

- NHS Redress Act 2006

Banking

UK banking has two main parts.[2] First, the Bank of England administers monetary policy, influencing interest rates, inflation and employment, and it regulates the banking market with HM Treasury, the Prudential Regulation Authority and Financial Conduct Authority. Second, there are private banks, and some non-shareholder banks (co-operatives, mutual or building societies), that provide credit to consumer and business clients. Borrowing money on credit (and repaying the debt[3] later) is important for people expand a business, invest in a new enterprise, or purchase valuable assets more quickly than by saving. Every day, banks estimate the prospects of a borrower succeeding or failing, and set interest rates for debt repayments according their predictions of the risk (or average risk of ventures like it). If all banks together lend more money, this means enterprises will do more, potentially employ more people, and if business ventures are productive in the long run, society's prosperity will increase. If banks charge interest that people cannot afford, or if banks lend too much money to ventures that are unproductive, economic growth will slow, stagnate, and sometimes crash. Although UK banks, except the Bank of England, are shareholder or mutually owned, many countries operate public retail banks (for consumers) and public investment banks (for business). The UK used to run Girobank for consumers, and there have been many proposals for a "British Investment Bank" (like the Nordic Investment Bank or KfW in Germany) since the global financial crisis of 2007-2008, but these proposals have not yet been accepted.

The Bank of England provides finance and support to, and may influence interest rates of the private banks through monetary policy. It was originally established as a corporation with private shareholders under the Bank of England Act 1694,[4] to raise money for war with Louis XIV, King of France. After the South Sea Company collapsed in a speculative bubble in 1720, the Bank of England became the dominant financial institution, and acted as a banker to the UK government and other private banks.[5] This meant, simply by being the biggest financial institution, it could influence interest rates that other banks charged to businesses and consumers by altering its interest rate for the banks' bank accounts.[6] It also acted as a lender through the 19th century in emergencies to finance banks facing collapse.[7] Because of its power, many believed the Bank of England should have more public duties and supervision. The Bank of England Act 1946 nationalised it. Its current constitution, and guarantees of a degree of operational independence from government, is found in the Bank of England Act 1998. Under section 1, the bank's executive body, the "Court of Directors" is "appointed by Her Majesty", which in effect is the Prime Minister.[8] This includes the Governor of the Bank of England (currently Mark Carney) and up to 14 directors in total (currently there are 12, 9 men and 3 women[9]).[10] The Governor may serve for a maximum of 8 years, deputy governors for a maximum of 10 years,[11] but they may be removed only if they acquire a political position, work for the bank, are absent for over 3 months, become bankrupt, or "is unable or unfit to discharge his functions as a member".[12] This makes removal hard, and potentially a court review. A sub-committee of directors sets pay for all directors,[13] rather than a non-conflicted body like Parliament. The Bank's most important function is administering monetary policy. Under BEA 1998 section 11 its objectives are to (a) "maintain price stability, and (b) subject to that, to support the economic policy of Her Majesty’s Government, including its objectives for growth and employment."[14] Under section 12, the Treasury issues its interpretation of "price stability" and "economic policy" each year, together with an inflation target. To change inflation, the Bank of England has three main policy options.[15] First, it performs "open market operations", buying and selling banks' bonds at differing rates (i.e. loaning money to banks at higher or lower interest, known "discounting"), buying back government bonds ("repos") or selling them, and giving credit to banks at differing rates.[16] This will affect the interest rate banks charge by influencing the quantity of money in the economy (more spending by the central bank means more money, and so lower interest) but also may not.[17] Second, the Bank of England may direct banks to keep different higher or lower reserves proportionate to their lending.[18] Third, the Bank of England could direct private banks adopt specific deposit taking or lending policies, in specified volumes or interest rates.[19] The Treasury is, however, only meant to give orders to the Bank of England in "extreme economic circumstances".[20] This should ensure that changes to monetary policy are undertaken neutrally, and artificial booms are not manufactured before an election.

Outside the central bank, banks are mostly run as profit-making corporations, without meaningful representation for customers. This means, the standard rules in the Companies Act 2006 apply. Directors are usually appointed by existing directors in the nomination committee,[21] unless the members of a company (invariably shareholders) remove them by majority vote.[22] Bank directors largely set their own pay, delegating the task to a remuneration committee of the board.[23] Most shareholders are asset managers, exercising votes with other people's money that comes through pensions, life insurance or mutual funds, who are meant to engage with boards,[24] but have few explicit channels to represent the ultimate investors.[25] Asset managers rarely sue for breach of directors' duties (for negligence or conflicts of interest), through derivative claims.[26] However, there is some public oversight through the bank licensing system.[27] Under the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 section 19 there is a "general prohibition" on performing a "regulated activity", including accepting deposits from the public, without authority.[28] The two main UK regulators are the Prudential Regulation Authority and the Financial Conduct Authority. Once a bank has received authorisation in the UK, or another member state, it may operate throughout the EU under the terms of the host state's rules: it has a "passport" giving it freedom of establishment in the internal market. Since the Credit Institutions Directive 2013,[29] there are some added governance requirements beyond the general framework: for example, duties of directors must be clearly defined, and there should be a policy on board diversity to ensure gender and ethnic balance. If the UK had employee representation on boards, there would also be a requirement for at least one employee to sit on the remuneration committee,[30] but this step has not yet been taken.

While banks perform an essential economic function, supported by public institutions, the rights of bank customers have generally been limited to contract. In general terms and conditions, customers receive very limited protection. The Consumer Credit Act 1974 sections 140A to 140D prohibit unfair credit relationships, including extortionate interest rates. The Consumer Rights Act 2015 sections 62 to 65 prohibit terms that create contrary to good faith, create a significant imbalance, but the courts have not yet used these rules in a meaningful way for consumers.[31] Most importantly, since Foley v Hill the courts have held customers who deposit money in a bank account lose any rights of property by default: they apparently have only contractual claims in debt for the money to be repaid.[32] If customers did have property rights in their deposits, they would be able to claim their money back upon a bank's insolvency, trace the money if it had been wrongly paid away, and (subject to agreement) claim profits made on the money. However, the courts have denied that bank customers have property rights.[33] The same position has generally spread in banking practice globally, and Parliament has not yet taken the opportunity to ensure banks offer accounts where customer money is protected as property.[34] Because insolvent banks do not, governments have found it necessary to publicly guarantee depositors' savings. This follows the model, started in the Great Depression,[35] the US set up the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, to prevent bank runs. In 2017, the UK guaranteed deposits up to £85,000,[36] mirroring an EU wide minimum guarantee of €100,000.[37] Moreover, because of the knock-on consequences of any bank failure, because bank debts are locked into a network of international finance, government has found it practically necessary to prevent banks going insolvent. Under the Banking Act 2009 if a bank is going into insolvency, the government may (and usually will if "the stability of the financial systems" is at stake) pursue one of three "stabilisation options".[38] The Bank of England will either try to ensure the failed bank is sold onto another private sector purchaser, set up a subsidiary company to run the failing bank's assets (a "bridge-bank"), or for the UK Treasury to directly take shares in "temporary public ownership". This will wipe out the shareholders, but will keep creditors' claims in tact. One method to prevent bank insolvencies, following the "Basel III" programme of the international banker group, has been to require banks hold more money in reserve based on how risky their lending is. EU wide rules in the Capital Requirements Regulation 2013 achieve this in some detail, for instance requiring proportionally less in reserves if sound government debt is held, but more if mortgage-backed securities are held.[39]

Natural resources

Natural resources have historically been critical for energy and raw materials in the UK economy. Before the industrial revolution, energy and heating needs were served mainly by burning timber. The development of the steam engine, particularly after James Watt's patents in 1775, and rail transport led coal to be the UK's dominant energy source, now governed under the Coal Industry Act 1994.[40] The development of the internal combustion engine in the late 19th century, led to a gradual displacement of coal by oil and gas. In the 21st century, because of critical threat of climate damage caused by human beings burning coal, oil and gas (or any fossil fuel releasing carbon dioxide and greenhouse gases), the UK is trying to shift to energy based on zero-carbon: wind, hydro or solar based power. In 2015, the UK's energy consumption was 47% petroleum, 29% natural gas, 18% electricity and 5% other,[41] but the growth of renewable electricity, and the introduction of electric vehicles is increasingly rapid. Under the Climate Change Act 2008, the UK government is bound to ensure there is an 80% reduction of carbon emissions compared to 1990 levels, when the Kyoto Protocol was drafted. This is meant to prevent the damage from extreme weather, flooding and coastlines going under the sea. The scientific community takes the view that, while the oil and gas industry still provides energy, it must be phased out.

Although both coal and oil production were publicly owned in the past,[42] coal, oil and gas extraction is performed today by private corporations under government licence. The largest entities include BP, Shell, but also now joined by entirely foreign firms such as Apache, Talisman, CNR, TAQA or Cuadrilla.[43] This means that ordinary UK company law (or US corporate law) sets the governance rights of oil and gas corporations, with board of directors invariably removable only by shareholders (typically large asset managers). The Petroleum Act 1998 section 2, rights of land ownership do not equate to rights to oil and gas (or hydrocarbons) underneath. In Bocardo SA v Star Energy UK Onshore Ltd, the Supreme Court did hold that a landowner may sue a company for trespass if it drills under its land without permission, but a majority held that damages will be nominal.[44] This meant that a landowner in Surrey was only able to recover £1000 when a licensed oil company drilled a diagonal well 800 to 2800 feet under its property, and not the £621,180 awarded by the High Court to reflect a share of the oil profits.[45] Similarly, under the Continental Shelf Act 1964 section 1 rights "outside territorial waters with respect to the sea bed and subsoil and their natural resources" are "vested in Her Majesty." Since 1919, the Crown has prohibited searching and boring for oil and gas without a licence.[46] Under the Energy Act 2016, licensing is managed by the Oil and Gas Authority.[47] Under section 8, the OGA should hand out licences so as to minimise future public expense, secure the energy supply, ensure storage of carbon dioxide, fully collaborate with the UK government, innovation, and stable regulation to encourage investment. Overshadowing this is the duty in PA 1998 sections 9A-I on the Secretary of State for ‘maximising the economic recovery of UK petroleum’.[48] The Secretary of State may give directions to the OGA in the interests of national security, or the public in exceptional circumstances,[49] while the OGA is nominally capable of funding itself through fees on license applicants and holders.[50] In the process of licensing, the Hydrocarbons Licensing Directive Regulations 1995 require objective, transparent and competitive criteria to be applied by OGA.[51] Under regulation 3, the OGA should consider an applicants technical and financial capability, price, previous conduct, and refuse all applications if none are satisfactory, while regulation 5 requires that all criteria to be applied are stated in the public notice for tenders. Under PA 1998 section 4, model licence clauses are prescribed by the Secretary of State, for instance in the Petroleum Licensing (Production) (Seaward Areas) Regulations 2008. Schedule 1's model clauses give the OGA discretion over the licence term, the licensee's obligation to submit its work programme, revocation on breach of a licence, arbitration for disputes, or health and environmental safety.[52] For onshore oil and gas extraction, and particularly hydraulic fracturing (or "fracking"), there are further requirements that must be fulfilled. For fracking, these include negotiating with landowners where a drill site is situated, getting the Mineral Planning Authority's approval for exploratory wells, consent from the council under the Town and Country Planning Act 1990 section 57, getting permission for disposing of hazardous waste and inordinate water use,[53] and finally consent from the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy.[54] In R (Frack Free Balcombe Residents Association) v West Sussex CC the resident group in Balcombe lost an action for judicial review of their Council's planning permission for Cuadrilla Balcombe Ltd to explore the potential to frack for shale gas. Large protests had opposed any steps toward fracking. However, Gilbart J held that the council had not been wrong in refusing to consider public opposition, and took the view would have acted unlawfully if it had considered the opposition.[55]

The interests of third parties and the public are partially represented through provisions on access to infrastructure, tax, and decommissioning. Under the Petroleum Act 1998 sections 17-17H there is a right of companies that are not owners of pipelines or gas interconnectors to use the infrastructure if there is spare capacity. This is not well utilised, and it usually left to commercial negotiation. Under the Energy Act 2011 sections 82-83 the Secretary of State can require a pipeline owner gives access on its own motion, apparently to reduce the problem of companies being too timid to exercise legal rights for fear of commercial repercussions. Taxation on oil and gas outputs have increasingly been reduced. Initially the Oil Taxation Act 1975 section 1 required a special Petroleum Revenue Tax, set as high as 75% of profits in 1983, but this ended for new licences after 1993, and then reduced from 50% in 2010, down to 0% in 2016.[56] Under the Corporation Tax Act 2010 sections 272-279A there is still a "ring fenced corporation tax", on individual fields that are "ring fenced" from other activities, set at 30%, but just 19% for smaller fields. An additional "supplementary charge" of 10% of profits was introduced in 2002 to ensure a ‘fair return’ to the state, because ‘oil companies [were] generating excess profits’.[57] Finally, under the Petroleum Act 1998 sections 29-45 require responsible decommissioning of oil and gas infrastructure. Under section 29, the Secretary of State can require a written notice of a decommissioning plan, on which stakeholders (e.g. the local community) must be consulted. Under section 30, notice regarding abandonment can be served on anyone who owns or has an interest in an installation. There are fines and offences for failure to comply. Estimates for the cost of decommissioning the UK's offshore platforms have been £16.9bn in the next decade, and £75bn to £100bn in total. A series of objections have been raised against the government's policy of cutting taxes while subsidising BP, Shell and Exxon for these costs.[58]

Energy

The need to stop climate damage, and create sustainable energy, has driven UK energy policy. The Climate Change Act 2008 section 1 requires an 80% reduction on 1990 greenhouse gas emissions by 2050, but this can always be made more stringent in line with science or international law.[59] Eliminating carbon emissions and fossil fuels means using only electricity (no more petrol or gas) and only using zero carbon inputs. In 2015, total UK energy use was composed of 18% electricity, 29% natural gas, and 49% petroleum.[60] Electricity itself, by 2015, was generated 24% from "renewable" sources, 30% gas, 22% coal,[61] and 21% nuclear.[62] "Renewable" sources were 48% wind, 9% solar (doubling each year to 2016), and 7.5% hydroelectric. But 35% of "renewable" electricity was "bioenergy", that is mostly timber, emitting more carbon than coal as it is burnt by converted coal stations.[63] Under the Energy Act 2013 section 1, the Secretary of State can set legally binding decarbonisation targets in electricity,[64] but the government not done this yet. Under section 131, the Secretary of State should, however, give Parliament an annual "Strategy and Policy Statement" on its strategic energy priorities, and how they will be achieved.[65]

Two main strategies have pushed a transition to renewable power. First, under the Electricity Act 1989 sections 32-32M, the Secretary of State was able to place renewables obligations on energy generating companies.[66] Large electricity generating companies (i.e. the big six, British Gas, EDF, E.ON, nPower, Scottish Power and SSE) had to buy fixed percentages of "Renewable Obligation Certificates" from renewable generators if they did not meet set quotas in their own electricity generators. This encouraged significant investment in wind and solar farms, although the Energy Act 2013 enabled the scheme to be closed to new installations over 5MW capacity in 2015 and all in 2017.[67] In Solar Century Holdings Ltd v SS for Energy and Climate Change a group of solar companies challenged the closure decision by judicial review. Solar Century Ltd claimed they had a legitimate expectation from the government in its previous policy documents for "maintaining support levels".[68] The Court of Appeal rejected the claim, because no unconditional promise was given. As a replacement, under EA 2013 sections 6-26 created a "contracts for difference" system to subsidise energy companies' investment in renewables. The government owned "Low Carbon Contracts Co." pays licensed energy generators money under contracts lasting, for example, 15 years, reflecting the difference between a predicted future price of electricity (a "reference price") and a predicted future price of electricity with more renewable investment (a "strike price"). The LCCC gets its money from a levy on the energy companies, which pass costs onto consumers. This system was apparently seen by the government as preferable to direct investment by taxing polluters' profits.[69] The second strategy to boost renewables was the Energy Act 2008's "feed-in tariff".[70] Electricity produced with renewables has to be paid a certain price by electricity companies: a "generation" rate (even if the producer uses the energy itself) and an "export" rate (when the producer sells to the grid).[71] In PreussenElektra AG v Schleswag AG a large energy company (now part of E.ON) challenged a similar scheme in Germany. It argued that the feed-in tariff operated like a tax to subsidise renewable energy companies, since non-renewable energy companies passed the costs on, and so should be considered an unlawful state aid, contrary to TFEU article 107.[72] The Court of Justice rejected the argument, holding that the redistributive effects were inherent in the scheme, as indeed they are in any change to private law.[73] Since then, feed-in tariffs have been considerably successful at promoting small scale electricity production by homes and business, and solar and wind in general.

- State ownership and stakeholder involvement

- TFEU arts 63 and 345 (free movement of capital and property ownership)

- Netherlands v Essent (2013) C‑105/12 (EU neutrality on public ownership)

- Gemeindeordnung Nordrhein-Westfalen 1994 §§107-114 (German state law on consumer voice)

- Licensing for generation. Planning permission. Consumer rights.

- Day-to-day responsibility falls on the energy regulator Ofgem, the Office of Gas and Electricity Markets.[74]

- Utilities Act 2000 ss 1, 5, 68 and Sch 1 (creates GEMA, Ministers can direct, governance)

- Electricity Act 1989 ss 3A-10O, 16-23, 32-47, Sch 6 (licensing, consumers, renewables)

- Electricity (Class Exemptions from the Requirement for a Licence) Order 2001 (n 3270)

- Standard Electricity Supply Licence ofgem.gov.uk

- Trump International Golf Club Scotland Ltd v Scotland [2015] UKSC 74 (windfarm planning)

- R (Gerber) v Wiltshire Council [2016] EWCA Civ 84 (solar farm planning)

- Gas Act 1986 ss 3, 4AA, 34 (regulatory objectives)

- Gas Act 1986 ss 5-11, 19 and 23-23G (gas licensing, consuemers, modification of conditions and appeal)

- Foster v British Gas plc (1990) C-188/89, [1991] 2 AC 306 (on nature of a public service)

- Nuclear Installations Act 1965 ss 1, 65-87 (nuclear licensing)

- Hinkley Point C nuclear power station

- ITER and fusion power

- Insolvency Act 1986 ss 72C-D and Sch 2A, para 10

- Energy Act 2011 ss 94-102

- Standard Electricity Supply Licence, conditions 7-10

- Carbon tax, Fuel price escalator and Climate Change Levy

Transport

- Rail

- Railways Act 1993 s 25 (rail to be franchised)

- Transport Act 1947, nationalised British Rail

- Privatisation of British Rail

- EU Directive 91/440 required member states to separate 'the management of railway operation and infrastructure from the provision of railway transport services, separation of accounts being compulsory and organisational or institutional separation being optional'

- Railways and Transport Safety Act 2003

- Ofrail

- Roads

- Highways Act 1555

- Highways Act 1562

- Turnpike Act 1707 and Turnpike trust

- Locomotive Acts 1861, 1865, 1878

- Local Government Act 1888, establishing county and borough councils, gave them powers to maintain roads

- Highways Act 1980

- Buses

- Privatisation of London bus services

- Transport Act 1985, councils transfer buses to companies

- Air traffic

- Airport Authority Act 1966, established the British Airports Authority, privatised in Airports Act 1986, and then wholly bought by a Spanish group, now BAA Limited

- British Overseas Airways Corporation or British Airways, combining the private British Airways Ltd. and the state owned Imperial Airways in 1939

- Waterways

Media and communication

- Internet

- Wikipedia

- YouTube and Google, Alphabet Inc

- Broadcasting

- White Paper on Broadcasting Policy (1946) Cmd 6852

- Communications Act 2003

- Ofcom

- Telecommunications

- National Telephone Company, a monopoly nationalised in 1911

- British Telecommunications Act 1981, splitting telephony from the post office

- Telecommunications Act 1984, privatising British telecom and establishing a regulator

- Post

- Telegraph

- Telegraph Act 1868

- Attorney General v Edison Telephone Co of London Ltd (1880–81) LR 6 QBD 244

Water

- Water Industry Act 1991

- Water Act 2003

- Ofwat

- Local authority water supply undertakings in England and Wales 1973

- EU water policy

- Water Framework Directive

- Water supply and sanitation in England and Wales

- Water supply and sanitation in Scotland

- Water supply and sanitation in Northern Ireland

- Sanitation

- John Snow (physician) and Broad Street cholera outbreak of 1854

- Great Stink of 1858, Joseph Bazalgette and the London sewerage system

- Public Health Act 1866, duty on councils to deal with nuisances and drainage

Waste and environment

- Waste

- Environmental Protection Act 1990 establishes waste disposal authorities, e.g. Waste disposal authorities in London

- Household Waste Recycling Act 2003, at least 2 kinds of collection each week by 2010

- Landfill Directive 1999, reduce amounts going to landfill

- Waste Framework Directive, must have 50% of waste recycled by 2020

- Land management

- National Trust

- Common land

- Erection of Cottages Act 1588

- Inclosure Acts

- Commons Registration Act 1965 (and The common land and commoners of Ashdown Forest)

- Agricultural Holdings Act 1948 and Agricultural Holdings Act 1986 (c 5)

- Air

- Smoke Nuisance Abatement (Metropolis) Act 1853 and 1856

- Public Health (London) Act 1891

- City of London (Various Powers) Act of 1954 and Clean Air Act 1968

- Great Smog of 1952

- Clean Air Act 1956

Social insurance and care

- Pensions

- Unemployment insurance

- National Insurance Act 1911

- Jobseekers' Act 1995

- Social Security Contributions and Benefits Act 1992

- Universal credit

- Social care

- Social care in the United Kingdom, Social care in England, Social care in Scotland

- Care Standards Act 2000, the elderly and disabled

- National Health Service and Community Care Act 1990

- Children Act 1989 and orphanages

- Health and Social Care Act 2008

Housing and construction

- Housing of the Working Classes Act 1890

- Housing Act 1919, homes fit for heroes

- Housing Act 1930

- New Towns Act 1946

- Town and Country Planning Act 1947

- Housing Act 1980 right to buy scheme copied Horace Cutler's policy in the GLC, see also Estmanco Ltd v GLC

- Town and Country Planning Act 1990

- Housing Act 1996

- Affordability of housing in the United Kingdom

- Town and country planning in the United Kingdom

- Directive on the energy performance of buildings (Directive 2002/91/EC)

Marketplaces and industry

- Marketplaces

- Borough Market Act 1754

- Covent Garden Act 1813

- Petticoat Lane Market Act 1936

- Ipswich Market Act 2004

- Supermarkets

- Tesco, Sainsbury's, Asda, Waitrose, M&S, Lidl, Aldi

- Networks, Amazon Inc, EBay

- London Stock Exchange

- Industry and manufacturing

- National Enterprise Board 1975, a State holding company for full or partial ownership of industrial undertakings

- British Steel Corporation 1967

- British Leyland Motor Corporation 1976 became British Leyland upon nationalisation. Privatised in 1986 to British Aerospace.

- British Aerospace 1977, combining the major aircraft companies British Aircraft Corporation, Hawker Siddeley and others. British Shipbuilders - combining the major shipbuilding companies including Cammell Laird, Govan Shipbuilders, Swan Hunter, Yarrow Shipbuilders

- Rolls-Royce (1971) Ltd

Public safety

- Military

- Ministry of Defence (United Kingdom)

- BAE Systems

- Reserve Forces Act 1996 (c 14)

- Armed Forces Act 2006 and Armed Forces Act 2016

- Police

- Metropolitan Police Act of 1829

- Metropolitan Police Act 1839

- County Police Acts

- Law enforcement in the United Kingdom and History of law enforcement in the United Kingdom

- Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 and Police Act 1996

- Independent Police Complaints Commission est 2004

- Prisons

- Panopticon 1775

- West Indian Prisons Act 1838

- Prison Act 1877

- Her Majesty's Prison Service

- Her Majesty's Young Offender Institution

- List of prisons in the United Kingdom

- Fire

Theory

- A Smith, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (1776) Bk I, ch 8, Bk V, ch 1 §§69-129

- JS Mill, Principles of Political Economy (1848) Book IV, ch VI and Book V, ch XI, §11

- K Marx, Capital: A Critique of Political Economy (1867) vol I, chs 13, 32 and 33 and vol III, ch 27

- S Webb and B Webb, Industrial Democracy (1897) Part III, ch 2 (655-662, 671-672, 692) and ch 4 (847-8)

- S Webb and B Webb, The History of Trade Unionism (Revised edn 1920) Appendix VIII

- K Kautsky, The Labour Revolution (1924) ch III, VIII(e)

- AA Berle, ‘Property, Production and Revolution’ (1965) 65 Columbia Law Review 1-20

- AO Hirschman, Exit, Voice and Loyalty (1971) chs 1-3 (only 19-43)

- T Raiser, ‘The Theory of Enterprise Law in the Federal Republic of Germany’ (1988) 36(1) American Journal of Comparative Law 111

- H Hansmann and R Kraakman, ‘The End of History for Corporate Law’ (2000) 89 Georgetown LJ 439

- S Deakin, ‘The Corporation as Commons: Rethinking Property Rights, Governance and Sustainability in the Business Enterprise’ (2012) 37(2) Queen’s Law Journal 339

- JE Stiglitz and JK Rosengard, The Economics of the Public Sector (3rd edn 2015)

- JA Schumpeter, Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy (1942)

- GJ Stigler, ‘The Theory of Economic Regulation’ (1971) 2(1) BJEMS 3 (on regulatory ‘capture’)

- FA Hayek, The Constitution of Liberty (1976) ch 12, especially at 184-5

- R Nader, M Green and J Seligman, Taming the Giant Corporation (1976)

- RE Freeman, Strategic Management: a Stakeholder Approach (1984)

- OE Williamson, The Economic Institutions of Capitalism (1985)

- H Hansmann, The Ownership of Enterprise (1996)

- JE Parkinson, ‘Models of the Company and the Employment Relationship’ (2003) 41 BJIR 481

See also

- Public service law in the United States

- UK competition law

- European Union competition law

- Economics of the public sector

- Universal service fund

- Universal service

- Coproduction (public services)

Notes

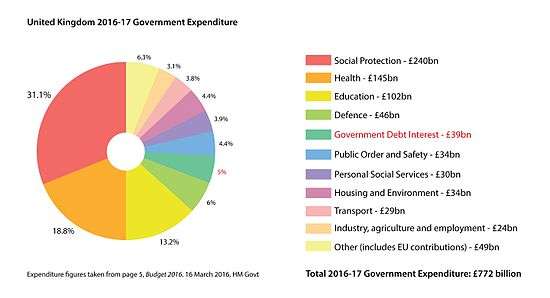

- ↑ "UK 2016 Budget" (PDF). p. 5.

- ↑ See EP Ellinger, E Lomnicka and CVM Hare, Ellinger's Modern Law of Banking (2011) chs 1-2 and 5

- ↑ Debt capital finance contrasts with equity capital finance, where an investor buys shares, invariably with voting rights, in a company. Debt finance usually keeps the borrower in control of their business, subject to any restrictive covenants and the need to repay the debt.

- ↑ 5 & 6 Will & Mar c 20. The Bank of England Act 1716 widened its borrowing power. The Bank Restriction Act 1797 removed a requirement to convert notes to gold on demand. The Bank Charter Act 1844 gave the bank sole rights to issue notes and coins.

- ↑ EP Ellinger, E Lomnicka and CVM Hare, Ellinger’s Modern Banking Law (5th edn 2011) ch 2, 30

- ↑ So, if the Bank of England raised its interest rate for Barings Bank's account with it, Barings would probably try to raise its interest rates for customers with Barings Bank accounts (unless competition was very tight, in which case its profits would have to be reduced).

- ↑ See W Bagehot, Lombard Street: A Description of the Money Market (1873) discussing Overend, Gurney and Co

- ↑ By contrast the US Federal Reserve Act of 1913, 12 USC §241, requires that on advice and consent of the Senate, appointments by the President ‘shall have due regard to a fair representation of the financial, agricultural, industrial and commercial interests, and geographical divisions of the country.’ Under §302, in the Federal Reserve system of constituent banks, three are chosen by and to represent stockholding banks, six others, represent the public and elected to represent stakeholders. In the EU, TFEU art 283(2), states the European Central Bank's Executive Board (a president, vice president and four members) are appointed by the European Council by qualified majority, after consulting the European Parliament and the Governing Council of the ECB. The Governing Council is itself the Executive Board plus governors of the national central banks using the euro. The term is 8 years, non-renewable, and they can only be removed for gross misconduct after review by the CJEU: ECB Statute arts 10-11.

- ↑ See 'Court of Directors' on bankofengland.co.uk

- ↑ BEA 1998 s 1A allows the Treasury to add directors, or reduce the number of directors, after consultation, with some limitations.

- ↑ BEA 1998 Sch 1, paras 1-2

- ↑ BEA 1998 Sch 1, paras 7-8

- ↑ BEA 1998 Sch 1, paras 14

- ↑ In the US, the Federal Reserve Act of 1913, 12 USC §225 states ‘The Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System and the Federal Open Market Committee shall maintain long run growth of the monetary and credit aggregates commensurate with the economy’s long run potential to increase production, so as to promote effectively the goals of maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates.’ Under TFEU art 9, and see also 127 and 119-150 the EU should aim at a "high level of employment". By contrast TEU art 3(3) says it should be ‘aiming at full employment’. See M Roth, ‘Employment as a Goal of Monetary Policy of the European Central Bank’ (2015) ssrn.com.

- ↑ R Cranston, Principles of Banking Law (2002) 121-122

- ↑ In the EU, TFEU art 123 contains a prohibition on the European Central Bank lending money to governments, but in Gauweiler v Deutsche Bundestag (2015) C-62/14 the CJEU approved the use of outright monetary transactions to buy Greek government debt on secondary markets (to support the euro) was lawful.

- ↑ Cranston (2002) 121, ‘This will typically, in turn, produce a change in the base rates of the banks.’

- ↑ BEA 1946 s 4(3). No order has been issued, but banks generally comply with the Bank of England's suggested reserve ratios. Cranston (2002) 121, ‘The size of the reserves clearly determines the volume of money in circulation and the extent to which a bank can itself extend credit to its customers.’

- ↑ See Monetary Control (1980) Cmnd 7858.

- ↑ BEA 1998 s 19

- ↑ Companies (Model Articles) Regulations 2008, Sch 3, para 20 and UK Corporate Governance Code 2016 section B

- ↑ Companies Act 2006 ss 168-9

- ↑ Companies (Model Articles) Regulations 2008, Sch 3, para 23 and UK Corporate Governance Code 2016 section D

- ↑ UK Corporate Governance Code 2016, section E

- ↑ See E McGaughey, 'Does corporate governance exclude the ultimate investor?' (2016) Journal of Corporate Law Studies

- ↑ Companies Act 2006 ss 170-77, 260-263

- ↑ Before FSMA 2000 ss 19-23 and 418-9, the Banking Act 1979 introduced the formal authorisation requirements.

- ↑ See also Credit Institutions Directive 2013/36/EU arts 8-14

- ↑ 2013/36/EU arts 88-96

- ↑ Credit Institutions Directive 2013 (2013/36/EU art 95, "If employee representation... is provided for by national law, the remuneration committee shall include one or more employee representatives."

- ↑ See Office of Fair Trading v Abbey National plc [2009] UKSC 6 and Director General of Fair Trading v First National Bank plc [2001] UKHL 52

- ↑ (1848) 2 HLC 28

- ↑ Vincent v Trustee Savings Banks Central Board [1986] 1 WLR 1077, denying that the Trustee Savings Bank customers were, despite the name of the bank, in any trustee-beneficiary relation, either at common law or under statute. The customers, apparently, only had contractual rights.

- ↑ See the Safety Deposit Current Accounts Bill 2008 cls 1-2, proposing a proprietary saving account option.

- ↑ Banking Act of 1933

- ↑ Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 ss 214-215

- ↑ See the Deposit Guarantee Directive 2014/49/EU

- ↑ See Banking Act 2009 ss 1, 7-13

- ↑ (EU) No 575/2013, arts 114-134

- ↑ The relevant historical bodies were the Coal Commission from 1933, the National Coal Board, and then British Coal. See also, Atomic Energy Act 1946, Pt III, which provides an unused framework for uranium extraction. Uranium deposits exist in Scotland, but not in large quantities, and given opposition to nuclear mining and weaponry, imports from Australia and elsewhere have been preferred.

- ↑ DBEIS, Digest of UK Energy Statistics (2016) ch 1

- ↑ The Coal Industry Nationalisation Act 1946 brought coal under government ownership, 27 years after the recommendations (albeit divided) of the Coal Industry Commission Act 1919. See Scottish Insurance Corp Ltd v Wilsons & Clyde Coal Co Ltd [1949] AC 462. The Petroleum and Submarine Pipe-lines Act 1975 set up the British National Oil Corporation as a public competitor to the private sector, but was privatised by the following government.

- ↑ cf MM Roggenkamp, C Redgwell, A Rønne, and I Guayo (eds), Energy law in Europe: national, EU and international regulation (2016) ch 14, 1058

- ↑ [2010] UKSC 35, [2011] 1 AC 380, Lord Hope and Lord Clarke dissenting.

- ↑ Previously BP Petroleum Developments Ltd v Ryder [1987] 2 EGLR 233 had held that statutory provisions did not enable compensation by reference to the value of oil deposits.

- ↑ See the Petroleum (Production) Act 1918, Petroleum (Production) Act 1934 s 1, Petroleum Act 1998 s 3

- ↑ EA 2016 s 2 and Sch 1 transferred functions previously exercised by the relevant Secretary of State or Minister, particularly the PA 1998 s 3 power to licence.

- ↑ It is not clear how this fits with the goals for preventing climate damage, in the Climate Change Act 2008 s 1

- ↑ EA 2016 s 9

- ↑ EA 2016 ss 12-13

- ↑ Based on the Hydrocarbons Directive 94/22/EC arts 2-6

- ↑ SI 2008/225 clauses 4-7, 16-17, 41-42, 43 and 23 or 45

- ↑ See Environmental Permitting (England and Wales) Regulations 2010 and Water Resources Act 1991

- ↑ See E Albrecht and D Schneemann, ‘Fracking in the United Kingdom: Regulatory Challenges between Resource Mobilisation and Environmental Protection’ [2014] CCLR 238. The DBEIS consults with the Environment Agency, Health and Safety Executive and the Health and Protection Agency.

- ↑ [2014] EWHC 4108 (Admin), [128]

- ↑ Finance Act 2016 s 140(1)

- ↑ Corporation Tax Act 2010 s 330. This did go up to 20% in 2006, but was since reduced.

- ↑ e.g. 'Taxpayers may be liable for North Sea decommissioning bill, says study' (21 November 2016) BBC News

- ↑ CCA 2008 ss 1-2. This is reflected in the Renewable Energy Directive 2009 art 3 and Annex I

- ↑ DBEIS, Digest of UK Energy Statistics (2016) ch 1

- ↑ There are 9 plants left, but all are converting to biomass or closing by 2025. However, Open-pit coal mining in the United Kingdom still runs.

- ↑ DBEIS, Digest of UK Energy Statistics (2016) ch 5

- ↑ See DBEIS, Digest of UK Energy Statistics (2016) ch 6. The UN rules and the Renewable Energy Directive 2009 art 17 and Annex V enable "biomass" and "biofuel" to count toward reducing greenhouse gases, even though burning wood produces carbon emissions, on the theory that plants (unlike coal or gas) absorb carbon while they grow supposedly neutralising emissions once they burn. This logic is criticised for not accounting for the environmental damage of deforestation, and the impact of short-term emissions, regardless of the "sustainability" criteria in art 17. M Le Page, ‘The Great Carbon Scam’ (21 September 2016) 231 New Scientist 20–21

- ↑ EA 2013 ss 1-4, stating targets must begin with a carbon budget including the year 2030.

- ↑ EA 2013 ss 131-138

- ↑ Inserted by EA 2008 ss ss 37-40, originally introduced by the Utilities Act 2000 ss 62-67. Known as a "renewable portfolio standard" in the US.

- ↑ See the Renewables Obligation Closure Order 2014 and Renewables Obligation Closure (Amendment) Order 2015 art 2, made under Electricity Act 1989 ss 32K-L

- ↑ [2016] EWCA Civ 117

- ↑ Planning our electric future: a White Paper for secure, affordable and low‑carbon electricity (2011) Cm 8099, 148-150

- ↑ EA 2008 ss 41-43 on the feed-in tariffs.

- ↑ Reduction in the rates was successfully challenged in Breyer Group Plc v Department of Energy and Climate Change [2015] EWCA Civ 408 and SS for Energy and Climate Change v Friends of the Earth [2012] EWCA Civ 28

- ↑ (2001) C-379/98

- ↑ See also the Opinion of AG Jacobs, "If the argument of the Commission and PreussenElektra were to be accepted then all sums which one person owes another by virtue of a given law would have to be considered to be State resources. That seems an impossibly wide understanding of the notion."

- ↑ The technical name is the Gas and Electricity Markets Authority (GEMA), but the older name is preferred.

References

- Articles

- JR Commons, ‘The Webbs’ Constitution for the Socialist Commonwealth’ (1921) 11(1) American Economic Review 82

- ACL Davies, ‘This Time, it’s for Real: The Health and Social Care Act 2012’ (2013) 76(3) Modern Law Review 564

- TR Gourvish, ‘British Rail’s “Business-Led” Organization, 1977-1990: Government-Industry Relations in Britain’s Public Sector’ (1990) 64(1) Business History Review 109

- T Prosser, ‘Public Service Law: Privatization’s Unexpected Offspring’ (2000) 63(4) Law & Contemporary Problems 63

- WA Robson, ‘The Public Corporation in Britain Today’ (1950) 63(8) Harvard Law Review 1321

- H Skovgaard-Petersen, ‘There and back again: portability of student loans, grants and fee support in a free movement perspective’ (2013) 38(6) European Law Review 783

- Books

- R Cranston, Principles of Banking Law (2002) chs 3-5

- EP Ellinger, E Lomnicka and CVM Hare, Ellinger’s Modern Banking Law (5th edn 2011) chs 2 and 5

- D Farrington and D Palfreyman, The Law of Higher Education (2nd edn 2012) chs 4-5 and 12

- G Gordon et al, Oil and Gas Law: Current Practice and Emerging Trends (2010) ch 4

- L Hannah, Electricity before Nationalisation: A Study of the Development of the Electricity Supply Industry to 1948 (1979)

- E Jackson, Medical Law: Texts, Cases and Materials (4th edn 2016) ch 2

- A Johnston and G Block, EU Energy Law (2012) ch 7

- J Montgomery, Health care law (2002) chs 3-4

- Tony Prosser, The limits of competition law (2004)

- T Wheelwright, Oil and World Politics: From Rockefeller to the Gulf War (1991)