Unetice culture

| |

| Geographical range | Europe |

|---|---|

| Period | Bronze Age Europe |

| Dates | c. 2300 – c. 1600 BC |

| Type site | Únětice |

| Preceded by | Beaker culture |

| Followed by | Tumulus culture |

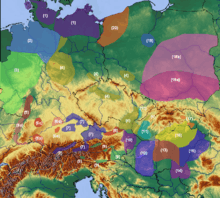

The Únětice culture (Czech pronunciation: [ˈuːɲɛcɪt͡sɛ], Czech Únětická kultura, German Aunjetitzer Kultur, Polish Kultura unietycka) is an archaeological culture at the start of the Central European Bronze Age, dated roughly to about 2300–1600 BC. The eponymous site for this culture, the village of Únětice, is located in the central Czech Republic, northwest of Prague. Today, this archaeological culture is known from Czech Republic and Slovakia from about 1,400 sites, from Poland (550 sites) and Germany (about 500 sites and loose finds locations).[1] The Únětice culture is also known from north-eastern Austria (in association with the so-called the Böheimkirchen Group), and from western Ukraine.

Sub-groups

| ↑ Chalcolithic |

|

Near East (c. 3300–1200 BC)

South Asia (c. 3000–1200 BC) Europe (c. 3200–600 BC)

China (c. 2000–700 BC) |

| ↓Iron Age |

The Únětice culture originated in the territories of contemporary Bohemia. Ten local sub-groups can be distinguished in its classical phase:[2]

- Bohemia Group[3]

- Moravia Group[4]

- Slovakia Group; following the so-called Nitra Group[5]

- Lower Austria Group[6]

- Central Germany Group[7]

- Lower Saxony Group[8][9]

- Lower Lusatia Group[10]

- Silesia Group[11][12]

- Greater Poland (Kościan) Group[13][14]

- Galicia (Western Ukraine) Group[15]

History of research

The Únětice culture was discovered by Czech surgeon and amateur archaeologist Čeněk Rýzner (1845-1923), who in 1879 found a cemetery of over 50 inhumations on Holý Vrch, the hill overlooking the village of Únětice. At the same time the first Úněticean burial ground was unearthed in Southern Moravia in Měnín by A. Rzehak. Following these initial discoveries and until the nineteen thirties, many more sites, primarily cemeteries, were identified, e.g. Němčice nad Hanou (1926), sites in vicinity of Prague, Polepy (1926–27) or Šardičky (1927).

In Germany, a Úněticean barrow in Leubingen was excavated by F. Klopfleisch already in 1877, however he incorrectly dated the monument to the Hallstatt during the Iron Age. In later years a main cluster of Úněticean sites in Central Germany was identified at Baalberge, Helmsdorf, Nienstedt, Körner, Leubingen, Halberstadt, Klein Quenstedt, Wernigerode, Blankenburg and Quedlinburg. At the same time, Adlerberg and Straubing groups were defined in 1918 by Schumacher.

In Poland, the first archaeologist associated with the discovery and identification of the Únětice culture was Hans Seger (1864-1943). Seger not only discovered several Úněticean sites and supervised pioneering excavations e.g. in Przecławice, but he also linked Bohemian EBA materials with similar assemblages in Lower Silesia. In Greater Poland, the first excavations at royal Úněticean necropolis of Łęki Małe were undertaken by Józef Kostrzewski in 1931, but major archaeological discoveries at this site were only made years later in 1953 and 1955.[16] In 1935 Kostrzewski published the first data and findings of the Iwno culture, another and contemporaneous with Únětice EBA, archaeological culture from Western Poland. In 1960 Wanda Sarnowska (1911-1989) begun excavations in Szczepankowice near Wrocław, southwest Poland, where a new group of barrows was unearthed. In 1969 she published a new monograph on the Únětice culture, in which she cataloged, analysed and described assemblages deriving from 373 known EBA Úněticean sites in Poland.[17][18]

The first unified chronological system (relative chronology) based on typology of ceramics and metal artifacts for the Únětice culture in Bohemia was introduced by Moucha in 1963.[19] This chronological system, consisting of six sub-phases was considered as valid for the Bohemian groups of the Únětice culture, and later was adapted in Poland[20] and in Germany.[21]

Recently the Únětice culture has been cited as a pan-European cultural phenomenon,[22] whose influence covered large areas due to intensive exchange, with Únětice pottery and bronze artefacts found from Ireland to Scandinavia, the Italian Peninsula, and the Balkans.[23] As such, it is candidate for a late community connecting a continuum of already scattered North-West Indo-European languages ancestral to Italic, Celtic, and Germanic, and perhaps to Balto-Slavic, where words were frequently exchanged, sharing a common lexicon and certain regional isoglosses[24]

Chronology

The culture corresponds to Bronze A1 and A2 in the chronological schema of Paul Reinecke:

- A1: 2300-1950 BC: triangular daggers, flat axes, stone wrist-guards, flint arrowheads

- A2: 1950-1700 BC: daggers with metal hilt, flanged axes, halberds, pins with perforated spherical heads, solid bracelets.

| Period | Reinecke 1924[25] | Moucha 1963[26] | Pleinerová 1967[27] | Bartelheim 1989[28] | Absolute dating | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Late Eneolithic | (A0) | 1. Proto-Únětice | Ia Ib | Older Únětice | 1 | 2300-2000 BC |

| 2. Old Únětice | ||||||

| 3. Middle Únětice | II | 2 | ||||

| 4. Pre-classical Únětice | ||||||

| Older Bronze Age | A1 | 5. Classic Únětice | III | Younger Únětice | 3 | 2000-1800 BC |

| A2 | 6. Post-classical Únětice | 1800-1700 BC | ||||

| Middle Bronze Age | B2 | Tumulus culture (west), Trzciniec culture (east) | ||||

Metal objects

The culture is distinguished by its characteristic metal objects including ingot torcs, flat axes, flat triangular daggers, bracelets with spiral-ends, disk- and paddle-headed pins and curl rings which are distributed over a wide area of Central Europe and beyond.

The ingots are found in hoards that can contain over six hundred pieces. Axe-hoards are common as well, the hoard of Dieskau (Saxony) contained 293 flanged axes. Thus, axes might have served as ingots as well. After about 2000 BC, this hoarding tradition dies out and is only resumed in the urnfield period. These hoards have formerly been interpreted as a form storage by itinerant bronze-founders or riches hidden because of enemy action. This is likely as even today weapons are hoarded underground to hide them from the enemy and axes were the primary weapon. Hoards containing mainly jewellery are typical for the Adlerberg-group.

Archaeological evidence suggests that the Únětice metal industry, though active and innovative, was concerned with producing weapons and ornaments mainly as status symbols for leading persons, rather than for widespread domestic use or for equipping large fighting forces - developments which would wait until later periods in European history. But the Adlerberg cemetery of Hofheim/Taunus, (Germany) contained the burial of a male who had died from an arrow-shot, the stone arrow-head still being located in his arm.

The famous Sky Disk of Nebra is associated with Central Germany groups of the Únětice culture.

Burials

From a technical point of view, Úněticean graves can be divided in two categories: flat graves and barrows.[29] The Únětice culture practiced skeletal inhumations, however occasionally cremation was also practised.

A typical Úněticean cemetery was situated near a settlement, usually on a hill or acclivity and in the vicinity of a creek or river. The distance between the cemetery and the adjacent settlement very rarely exceeds a kilometer. Cemeteries were usually spatially organized, with symmetrical rows or alleys.[30] Burials of the Únětice culture are orientated according to stars and the relative position of the sun on the horizon during the year, which indicate possibly quite advanced prehistoric astronomical observations.[31][32]

Flat graves

A typical Úněticean flat grave was a rectangular or oval pit (1.0-1.9 m long, 0.6-1.2m wide and 0.30-1.5m deep). Depending on the shape of the bottom and depth, graves can be divided into four sub-types:[33]

- rectangular,

- concave,

- trapezoid or

- hourglass.

One of the most prominent characteristic is the position of the body in grave pit. Deceased were buried always in north-south alignment, with head south facing east. The body lied in a grave usually in slightly contracted position. Exceptions from this rule are sporadic.

In classic phase (approx. 1850-1750 BC), Úněticean burial rite displays strong uniformity, regardless of the gender or age of the deceased. Men and women were buried in the same N-S position. The grave goods consisted of ceramic vessels (usually 1-5), bronze items (jewellery and private belongings, rings, hair clips, pins etc.), bone artifacts (amulets and tools, i.e. needles), occasionally flint tools (e.g. burial of Archer from Nowa Wieś Wrocławska buried with colour flint arrowheads).[34]

A body deposited within a grave might have been protected with organic mats or a coffin, but in the majority of cases there was no additional coverage of the corpse. Well known example of wicker-made coffin inhumation derives from Bruszczewo fortified settlement, nearby Poznań in Greater Poland.[35] In approximately 20% of burials, stone settings were found. Erection of a full stone setting or just a partial one (a few stones in the corners of grave) seems to be quite a common practice observed in all phases of the EBA in Central Europe.

Wooden coffins were discovered at several sites in e.g. Lower Silesia. The Únětice culture coffin burials can be divided in two types, equipped with:

- coffins of stretcher type, and

- coffins of canoe type.

Coffins were made of single block of wood. The most prominent example of rich cemetery containing many of such inhumations is Przecławice[36] nearby Wrocław. Coffin burials appear in Central Europe in the Neolithic and are well known from Bell Beaker and Corded Ware cultures in Moravia.[37]

Barrows- Princely graves

To date, over fifty Úněticean barrows have been found in Central Europe; the majority of monuments was published in archaeological literature, but only approximately 60% of that number has been excavated according to modern standards. Some of the tombs were found early in the 19th century, incorrectly identified, robbed or destroyed in other way (e.g. many tombs in Kościan County, Poland. The largest concentrations of Úněticean barrows, known in archaeological literature also as ’princely graves’, can be found:

- in Czech Republic- vicinity of Prague, e.g. Brandýs, Březno, Mladá Boleslav-Čejetičky-Choboty, Prague 5- Řeporyje, Prague 6- Bubeneč;

- in Central Germany: e.g. Leubingen, Helmsdorf, Baalberge, Dieskau II, Sömmerda I-II[38] and Groß Gastrose;

- in Poland- in Greater Poland: e.g. Łęki Małe I-V, in Silesia: e.g. Szczepankowice Ia-Ib, Kąty Wrocławskie.

The size of the tombs varies, and the biggest among all is monument associated with the Kościan Group of the Únětice Culture- barrow no 4 at Łęki Małe (diameter 50m, 5–6 m in high today). In classic phase typical ‘princely grave’ was approximately 25m in diameter, 5 m in high.

Trade

The Únětice culture had trade links with the British Wessex culture. Unetice metalsmiths mainly used pure copper; alloys of copper with arsenic, antimony and tin to produce bronze became common only in the succeeding periods. The cemetery of Singen is an exception, it contained some daggers with a high tin-content (up to 9%). They may have been produced in Brittany, where a few rich graves have been found in this period. Cornish tin was widely traded as well. A gold lunula of Irish design has been found as far south as Butzbach in Hessen (Germany). Amber was traded as well, but small fossil deposits may have been used as well as Baltic amber.

Settlements

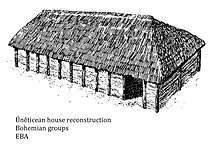

The most typical Úněticean housing structures are known from the Czech Republic. The houses were constructed of wood, with gable roof, rectangular in plan with entrance on western side. The roofs were built of straw and other similar organic materials, providing thermal isolation and protection from the rain. Because thatch was lighter, less timber was required in the roof structure to support it. Thatch is also versatile material when it comes to covering irregular roof structures and is naturally waterproof. The walls were constructed in wattle and daub technique. The walls were probably made of a woven lattice of wooden strips, also inside of the buildings, and later covered with a composite building material, a mixture of clay, sand, animal dung and straw. One of the houses discovered in Brezno in the Czech Republic was 24 m long and approximately 6.5 m wide.

One of the most characteristic features associated with settlements are storage pits of Únětice type. They were located beneath the houses, deep and spacious, with a cylindrical or slightly conical neck, arched walls and relatively flat bottom. Pits often served as a granary.

The vast majority of settlements consisted of several houses congregated in the communal space of the village or a hamlet. Larger fortified villages, with ramparts and wooden fortifications, were discovered as well, e.g. Bruszczewo in Greater Poland[39] or Radłowice in Silesia.[40] They played a role as local political centres, possibly also market places, facilitating the flow of goods and supplies.

Únětice tradition

Today, the Únětice culture is considered to be part of a wider pan-European cultural phenomenon, arising gradually between the second half of the third and at the beginning of second millennium.[41][22] The role of the Únětice Culture in the formation of Bronze Age Europe cannot be overrated. The rise and the existence of this original, expansive and dynamic populations mark one of the most interesting moments in European prehistory. The influence of this culture covered much larger areas mainly due to intensive exchange.[23] Únětice pottery and bronzes are thus found in Britain, Ireland, Scandinavia, Italy as well as the Balkans.

Strong impact of Úněticean metallurgical centres and pottery making traditions can be seen in other EBA groups, e.g. Adlerberg, Straubing, Singen, the Neckar-Ries and Upper-Rhine groups in Germany, as well as Unterwölbling in Austria. The Nitra Group, inhabiting southern Slovakia not only precedes chronologically the Únětice culture, but is also strongly culturally related to it. In later times, some elements of Úněticean pottery making traditions can be found in the Trzciniec culture as well.

Gold from Łęki Małe barrows, Poland; Photo. B.Walkiewicz, Poznan Archaeological Museum

Gold from Łęki Małe barrows, Poland; Photo. B.Walkiewicz, Poznan Archaeological Museum Bronze and gold from Central Germany, Photo.J.Liptak, LDA Sachsen-Anhalt

Bronze and gold from Central Germany, Photo.J.Liptak, LDA Sachsen-Anhalt Bronze necklace from Central Germany, Photo.J.Liptak, LDA Sachsen-Anhalt

Bronze necklace from Central Germany, Photo.J.Liptak, LDA Sachsen-Anhalt Uneticean halberds from Central Germany, Photo.J.Liptak, LDA Sachsen-Anhalt

Uneticean halberds from Central Germany, Photo.J.Liptak, LDA Sachsen-Anhalt Uneticean halberds from Central Germany II, Photo.J.Liptak, LDA Sachsen-Anhalt

Uneticean halberds from Central Germany II, Photo.J.Liptak, LDA Sachsen-Anhalt Bronze and gold from Central Germany, II, Photo.J.Liptak, LDA Sachsen-Anhalt

Bronze and gold from Central Germany, II, Photo.J.Liptak, LDA Sachsen-Anhalt Decorated bronze axe, Central Germany, Photo.J.Liptak, LDA Sachsen-Anhalt

Decorated bronze axe, Central Germany, Photo.J.Liptak, LDA Sachsen-Anhalt Halberd from Wroclaw, Silesian Group of the Unetice culture

Halberd from Wroclaw, Silesian Group of the Unetice culture Hoard of halberds -Dieskau II, Photo.J.Liptak, LDA Sachsen-Anhalt

Hoard of halberds -Dieskau II, Photo.J.Liptak, LDA Sachsen-Anhalt Gold jewelry from Leki Male, Poland, Photo.B.Walkiewicz, Poznan Archaeological Museum

Gold jewelry from Leki Male, Poland, Photo.B.Walkiewicz, Poznan Archaeological Museum Uneticean bronzes, Koscian Group, Photo. B.Walkiewicz, Poznan Archaeological Museum

Uneticean bronzes, Koscian Group, Photo. B.Walkiewicz, Poznan Archaeological Museum Typical necklace with open endings, EBA, Unetice culture, Photo. B.Walkiewicz, Poznan Archaeological Museum

Typical necklace with open endings, EBA, Unetice culture, Photo. B.Walkiewicz, Poznan Archaeological Museum Halbard, bronze, EBA, Unetice culture, Photo. B.Walkiewicz, Poznan Archaeological Museum

Halbard, bronze, EBA, Unetice culture, Photo. B.Walkiewicz, Poznan Archaeological Museum Uneticean daggers from Leki Male barrows, Photo. B.Walkiewicz, Poznan Archaeological Museum

Uneticean daggers from Leki Male barrows, Photo. B.Walkiewicz, Poznan Archaeological Museum Bronze jewelery from Leki Male, EBA, Unetice culture, Photo. B.Walkiewicz, Poznan Archaeological Museum

Bronze jewelery from Leki Male, EBA, Unetice culture, Photo. B.Walkiewicz, Poznan Archaeological Museum Uneticean hoard during exploration, 2012, Gorzow Wielkopolski, Poland; Polish Heritage Service photo

Uneticean hoard during exploration, 2012, Gorzow Wielkopolski, Poland; Polish Heritage Service photo Inventory of Helmsdorf barrow, Germany

Inventory of Helmsdorf barrow, Germany Uneticean pottery making tradition, Central Germany, Photo.J.Liptak, LDA Sachsen-Anhalt

Uneticean pottery making tradition, Central Germany, Photo.J.Liptak, LDA Sachsen-Anhalt Typical vessel dated to classic phase, Uneticean pottery making tradition, Central Germany, Photo.J.Liptak, LDA Sachsen-Anhalt

Typical vessel dated to classic phase, Uneticean pottery making tradition, Central Germany, Photo.J.Liptak, LDA Sachsen-Anhalt Vase on four legs, Typical vessel dated to classic phase, Uneticean pottery making tradition, Central Germany, Photo.J.Liptak, LDA Sachsen-Anhalt

Vase on four legs, Typical vessel dated to classic phase, Uneticean pottery making tradition, Central Germany, Photo.J.Liptak, LDA Sachsen-Anhalt Distinctive low and sharp base edge-the most characteristic feature of Uneticean ceramics, Turany, Brno, Czech Republic

Distinctive low and sharp base edge-the most characteristic feature of Uneticean ceramics, Turany, Brno, Czech Republic Bone artifacts, EBA, Unetice culture, Photo.J.Liptak, LDA Sachsen-Anhalt

Bone artifacts, EBA, Unetice culture, Photo.J.Liptak, LDA Sachsen-Anhalt Rake?-Bone tool from Bruszczewo fortified settlement in Central Poland, Unetice culture

Rake?-Bone tool from Bruszczewo fortified settlement in Central Poland, Unetice culture

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Unetice culture. |

References

- ↑ Zich B. 1996, Studien zur regionalen und chronologischen Gliederung der nördlichen Aunjetitzer Kultur, Berlin, p.5-19

- ↑ Pokutta D. 2013, Population Dynamics, Diet and Migrations of the Únětice culture in Poland, Gothenburg, p.25

- ↑ Pleinerová I. 1967, Únetická kultura v oblasti Krušných hor a jejím sousedství II, Památky archeologické 58, p. 1-36

- ↑ Bartelheim M. 1998, Studien zur böhmischen Aunjetitzer Kultur: Chronologie und chronologische Untersuchungen, vols.1- 2. Bonn

- ↑ Bátora J. 2000, Das Gräberfeld von Jelšovce/Slowakei. Ein Beitrag zur Frühbronzezeit im nordwestlichen Karpatenbecken, vols.1-2, Kiel

- ↑ Neugebauer J.W. 1994, Bronzezeit in Ostösterreich, Wien

- ↑ Zich B. 1996, Studien zur regionalen und chronologischen Gliederung der nördlichen Aunjetitzer Kultur, Berlin

- ↑ Zich B. 1996, Studien zur regionalen und chronologischen Gliederung der nördlichen Aunjetitzer Kultur, Berlin

- ↑ Gimbutas, M. 1965, Bronze Age cultures in Central and Eastern Europe, Hague-London, p.248, 261-265

- ↑ Zich B. 1996, Studien zur regionalen und chronologischen Gliederung der nördlichen Aunjetitzer Kultur, Berlin

- ↑ Sarnowska W. 1969, Kultura unietycka w Polsce, vol.1, Wrocław

- ↑ Pokutta D. 2013, Population Dynamics, Diet and Migrations of the Únětice culture in Poland, Gothenburg

- ↑ Lasak I. 2001, Epoka brązu na pograniczu śląsko-wielkopolskim. Część II. Zagadnienia kulturowo -osadnicze, Seria: Monografie Archeologiczne 6, Wrocław

- ↑ Machnik J. 1977, Frühbronzezeit Polens (Übersicht über die Kulturen und Kulturgruppen), Wrocław

- ↑ Pasternak J. 1933, Перша бронзова доба в Галичині в світлі нових розкопок, Записки НТШ Львів, vol.152, p. 63-112

- ↑ Kowiańska-Piaszykowa M. (ed.) 2008, Cmentarzysko kurhanowe z wczesnej epoki brązu w Łękach Małych w Wielkopolsce, Poznań

- ↑ Sarnowska W. 1969, Kultura unietycka w Polsce, vol.1, Wrocław

- ↑ Sarnowska W. 1975, Kultura unietycka w Polsce, vol.2, Wrocław

- ↑ Moucha V. 1963, Die Periodisierung der Úněticer Kultur in Böhmen, Sborník ČSSA 3, p. 9-60

- ↑ Machnik J. 1977, Frühbronzezeit Polens (Übersicht über die Kulturen und Kulturgruppen), Wrocław

- ↑ Müller J. 1999, Radiocarbonchronologie-Keramiktechnologie-Osteologie-Anthropologie-Raumanalysen. Beiträge zum Neolithikum und zur Frühbronzezeit im Mittelelbe-Saale-Gebiet, Bericht der Römisch-Germanischen Kommission 80, p. 28-211

- 1 2 Kristiansen, K., Larsson, T. 2005, The rise of Bronze Age Society. Travels, Transmissions and Transformations, Cambridge, p.108-118

- 1 2 Pokutta D.2013, Population Dynamics, Diet and Migrations of the Unetice culture in Poland, Gothernburg

- ↑ Gamkrelidze, T. V., and V. V. Ivanov. 1995. Indo-European and the Indo-Europeans: A Reconstruction and Historical Analysis of a Proto-Language and Proto-Culture. Part I: The Structure of Proto-Indo-European. Part II: Semantic Dictionary of Proto-IndoEuropean Language. Vol. 80. Walter de Gruyter, 1995. Edited by W. Winter. Vol. 80. Berlin / New York: Mouton de Gruyter

- ↑ Reinecke, P. 1924, Zur chronologischen Gliederung der süddeutschen Bronzezeit, Germania 8, p. 40-44

- ↑ Moucha V. 1963, Die Periodisierung der Úněticer Kultur in Böhmen, Sborník ČSSA 3, p. 9-60

- ↑ Pleinerová I. 1967, Únetická kultura v oblasti Krušných hor a jejím sousedství II, Památky archeologické 58, p. 1-36

- ↑ Bartelheim M. 1998, Studien zur böhmischen Aunjetitzer Kultur: Chronologie und chronologische Untersuchungen, vols.1- 2, Bonn

- ↑ Steffen C. 2010, Die Prunkgräber der Wessex-und der Aunjetitz-Kultur, BAR International Series 2160

- ↑ Butent-Stefaniak B. 1997, Z badań nad stosunkami kulturowymi w dorzeczu górnej i środkowej Odry we wczesnym okresie epoki brązu, Prace Komisji Archeologicznej 12, Wrocław-Warszawa-Kraków

- ↑ Romanow J., Wachowski K., Miszkiewicz B. 1973, Tomice, pow. Dzierżoniów. Wielokulturowe stanowisko archeologiczne, Wrocław

- ↑ Pokutta D 2013, Population Dynamics, Diet and Migrations of the Únětice culture in Poland, Gothenburg, p.71-74

- ↑ Pokutta D. 2013, Population Dynamics, Diet and Migrations of the Únětice culture in Poland, Gothenburg, p.52-59

- ↑ Pokutta D. 2013, Population Dynamics, Diet and Migrations of the Únětice culture in Poland, Gothenburg, p.81

- ↑ Müller, J., Czebreszuk, J., Kneisel, J. (eds.) 2010, Bruszczewo II. Ausgrabungen und Forschungen in einer prähistorischen Siedlungskammer Grosspolens. Badania mikroregionu osadniczego z terenu Wielkopolski, vols.1-2, Bonn, p.724-730

- ↑ Lasak I. 1988, Cmentarzysko ludności kultury unietyckiej w Przecławicach, Studia Archeologiczne 18, Wrocław

- ↑ Lasak I. 1982, Pochówki w trumnach drewnianych jako forma obrządku grzebalnego we wczesnym okresie epoki brązu w świetle badań w Przecławicach, woj. Wrocław, Silesia Antiqua 24, p. 89-108

- ↑ Klopfleisch, F. 1884, Die Grabhügel von Leubingen, Sömmerda und Nienstedt : allgemeine Einleitung : Charakteristik und Zeitfolge der Keramik Mitteldeutschlands, Historische Commission der Provinz Sachsen, Druck und Verl. von O. Hendel

- ↑ Müller, J., Czebreszuk, J., Kneisel, J. (eds.) 2010, Bruszczewo II. Ausgrabungen und Forschungen in einer prähistorischen Siedlungskammer Grosspolens. Badania mikroregionu osad¬niczego z terenu Wielkopolski, vols.1-2, Bonn.

- ↑ Lasak, I., Furmanek, M. 2008, Bemerkungen zum vermutlichen Wehrobjekt der Aunjetitzer Kultur in Radłowice in Schlesien, In: Müller, J., Czebreszuk, J., Kadrow, S. (eds.), Defensive Structures from Central Europe to the Aegean in the 3rd and 2nd millennia B.C, Studia nad pradziejami Europy Środkowej, vol. 5, Poznań-Bonn, p. 123-134

- ↑ Sosna, D. 2009, Social Differentiation in the Late Cooper Age and the Early Bronze Age in South Moravia (Czech Republic), BAR International Series 1994, Oxford

Sources

- J. M. Coles/A. F. Harding, The Bronze Age in Europe (London 1979).

- G. Weber, Händler, Krieger, Bronzegießer (Kassel 1992).

- R. Krause, Die endneolithischen und frühbronzezeitlichen Grabfunde auf der Nordterrasse von Singen am Hohentwiel (Stuttgart 1988).

- B. Cunliffe (ed.), The Oxford illustrated prehistory of Europe (Oxford, Oxford University Press 1994).

External links

- Nebra Sky Disk official website, State Museum of Saxony-Anhalt in Halle

- Úněticean settlement Area Brno-Tuřany photo gallery

- Gold from Leki Male barrows, Poznan Archaeological Muzeum

- Uneticean cemetery Prague East

- Greater Poland (Koscian) Group of the Unetice culture

- Henge-like sanctuary of the earliest Únětice Culture