Eardrum

- Not to be confused with the secondary tympanic membrane of the round window

| Eardrum (tympanic membrane, myringa) | |

|---|---|

| |

Right eardrum as seen through a speculum. | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | membrana tympanica; myringa |

| MeSH | A09.246.272.702 |

| Dorlands /Elsevier | Tympanic membrane |

| TA | A15.3.01.052 |

| FMA | 9595 |

|

| This article is one of a series documenting the anatomy of the |

| Human ear |

|---|

|

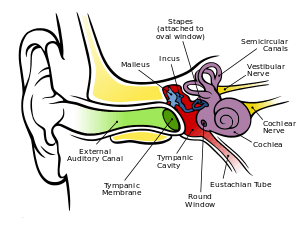

In the anatomy of humans and various other tetrapods, the eardrum, also called the tympanic membrane or myringa, is a thin, cone-shaped membrane that separates the external ear from the middle ear. Its function is to transmit sound from the air to the ossicles inside the middle ear, and then to the oval window in the fluid-filled cochlea. Hence, it ultimately converts and amplifies vibration in air to vibration in fluid. The malleus bone bridges the gap between the eardrum and the other ossicles.[1]

Rupture or perforation of the eardrum can lead to conductive hearing loss. Collapse or retraction of the eardrum can cause conductive hearing loss or cholesteatoma.

Placement inside the external acoustic canal

The oblique placement of the tympanic membrane both antero-posteriorly, medio-laterally and superoinferiorly causes it's superoposterior end to be more lateral to its anteroinferior end. From this you also understand that the superior part of the TM is also it's posterior part (maximum area is shared) while it's anterior part is also it's inferior part (again maximum area shared).

Structure

There are two general regions of the eardrum: the pars flaccida in the upper region and the pars tensa. The pars flaccida consists of two layers, is relatively fragile, and is associated with eustachian tube dysfunction and cholesteatomas. The larger pars tensa region consists of three layers: skin, fibrous tissue, and mucosa.Middle fibrous layer, which encloses the handle of malleus and has three types of fibres-the radial, circular and parabolic. It is comparatively robust and is the region most commonly associated with perforations.[2]

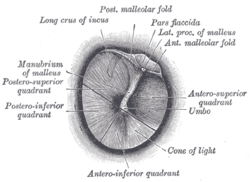

The pars tensa forms most of the tympanic membrane. Its periphery is thick and forms a fibrocartilaginous ring called the anulus tympanicus. The central part of the pars tensa is tented inward at the level of the tip of malleus and is called the umbo. When the eardrum is illuminated during an examination, a cone of light radiates from the tip of the malleus to the periphery in the antero-inferior quadrant. The pars flaccida is above the lateral process of the malleus between the notch of Rivinus and the anterior and posterior malleal folds. It appears slightly pinkish.

Nerve supply

Sensory innervation of the external surface of the tympanic membrane is mainly by the auriculotemporal nerve, a branch of the mandibular nerve [V3]. It also has contributions from the auricular branch of the vagus nerve [X], the facial nerve [VII] and a possible contribution from the glossopharyngeal nerve [IX]. Sensory innervation of the inner surface of the tympanic membrane is by the glossopharyngeal nerve [IX].[3]

Relations

The tympanic membrane is superiorly related to middle cranial fossa, posteriorly to the ear ossicles and the facial nerve, inferiorly to the parotid gland and anteriorly to the temporomandibular joint.

Umbo

The umbo is the most depressed part of the tympanic membrane. The manubrium of the malleus is firmly attached to the medial surface of the membrane as far as its center, which it draws toward the tympanic cavity; the lateral surface of the membrane is thus concave, and the most depressed part of this concavity is named the umbo.[4]

Clinical significance

Rupture

An unintentional perforated eardrum (rupture) has been described in blast injuries during conflict[5] and air travel, usually when the congestion of an upper respiratory infection has prevented equalization of pressure in the middle ear.[6] It happens in sport and recreation, such as swimming, diving with a poor entry into the water, scuba diving,[7] and martial arts.[8] In the published literature, 80% to 95% have recovered completely without intervention in two to four weeks.[9][10][11]

These injuries, even in a recreational or athletic setting, are blast injuries. Many will experience some short-lived hearing loss and ringing in the ear (tinnitus) but can be reassured that it, in all likelihood, will pass. A very few will experience temporary disequilibrium (vertigo). There may be some bleeding from the ear canal if the eardrum has been ruptured. Naturally, the foregoing reassurances become more guarded as the force of injury increases, as in military or combat situations.[11]

Surgical puncture for treatment of middle ear infections

The pressure of fluid in an infected middle ear onto the eardrum may cause it to rupture. Usually this consists of a small hole (perforation), which allows fluid to drain out. If this does not occur naturally, a myringotomy (tympanotomy, tympanostomy) can be performed. A myringotomy is a surgical procedure in which a tiny incision is created in the eardrum to relieve pressure caused by excessive buildup of fluid, or to drain pus from the middle ear. The fluid or pus comes from a middle ear infection (otitis media), which is a common problem in children. A tympanostomy tube is inserted into the eardrum to keep the middle ear aerated for a prolonged time and to prevent reaccumulation of fluid. Without the insertion of a tube, the incision usually heals spontaneously in two to three weeks. Depending on the type, the tube is either naturally extruded in 6 to 12 months or removed during a minor procedure.[12]

Those requiring myringotomy usually have an obstructed or dysfunctional eustachian tube that is unable to perform drainage or ventilation in its usual fashion. Before the invention of antibiotics, myringotomy without tube placement was also used as a major treatment of severe acute otitis media.[12]

In some cases the pressure of fluid in an infected middle ear is great enough to cause the eardrum to rupture naturally. Usually this consists of a small hole (perforation), from which fluid can drain.

Society and culture

The Bajau people of the Pacific intentionally rupture their eardrums at an early age to facilitate diving and hunting at sea. Many older Bajau therefore have difficulties hearing.[13]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Eardrum. |

- Middle ear

- Valsalva maneuver to equalize pressure across the eardrum

Additional images

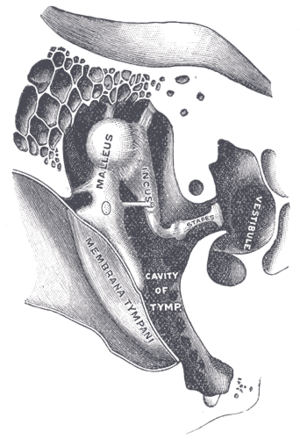

External and middle ear, opened from the front (right side)

External and middle ear, opened from the front (right side) Horizontal section through left ear; upper half of section

Horizontal section through left ear; upper half of section The right membrana tympani with the hammer and the chorda tympani, viewed from within, from behind, and from above

The right membrana tympani with the hammer and the chorda tympani, viewed from within, from behind, and from above Auditory tube, laid open by a cut in its long axis

Auditory tube, laid open by a cut in its long axis Chain of ossicles and their ligaments, seen from the front in a vertical, transverse section of the tympanum

Chain of ossicles and their ligaments, seen from the front in a vertical, transverse section of the tympanum Right eardrum as seen through a speculum

Right eardrum as seen through a speculum This is a normal left eardrum.

This is a normal left eardrum. Tympanic membrane viewed by otoscope

Tympanic membrane viewed by otoscope The oval perforation in this left tympanic membrane was the result of a slap on the ear

The oval perforation in this left tympanic membrane was the result of a slap on the ear A subtotal perforation of the right tympanic membrane resulting from a previous severe otitis media

A subtotal perforation of the right tympanic membrane resulting from a previous severe otitis media A normal human right tympanic membrane (eardrum)

A normal human right tympanic membrane (eardrum) Frog on leaf showing eardrum

Frog on leaf showing eardrum

References

This article incorporates text in the public domain from the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

- ↑ Purves, D; Augustine, G; Fitzpatrick, D; Hall, W; LaMantia, A; White, L; et al., eds. (2012). Neuroscience. Sunderland: Sinauer. ISBN 9780878936953.

- ↑ Marchioni D, Molteni G, Presutti L (February 2011). "Endoscopic Anatomy of the Middle Ear". Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 63 (2): 101–13. PMC 3102170

. PMID 22468244. doi:10.1007/s12070-011-0159-0.

. PMID 22468244. doi:10.1007/s12070-011-0159-0. - ↑ Drake, Richard L., A. Wade Vogl, and Adam Mithcell. Gray's Anatomy For Students. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone, 2015. Print. pg. 969

- ↑ Gray's Anatomy (1918)

- ↑ Ritenour AE, Wickley A, Retinue JS, Kriete BR, Blackbourne LH, Holcomb JB, Wade CE (February 2008). "Tympanic membrane perforation and hearing loss from blast overpressure in Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom wounded". J Trauma. 64 (2 Suppl): S174–8. doi:10.1097/ta.0b013e318160773e.

- ↑ Mirza S, Richardson H (May 2005). "Otic barotrauma from air travel". J Laryngol Otol. 119 (5): 366–70. PMID 15949100. doi:10.1258/0022215053945723.

- ↑ Green SM; Rothrock SG; Green EA= (October 1993). "Tympanometric evaluation of middle ear barotrauma during recreational scuba diving". Int J Sports Med. 14 (7): 411–5. PMID 8244609. doi:10.1055/s-2007-1021201.

- ↑ Fields JD, McKeag DB, Turner JL (February 2008). "Traumatic tympanic membrane rupture in a mixed martial arts competition". Current Sports Med Rep. 7 (1): 10–11. PMID 18296937. doi:10.1097/01.CSMR.0000308672.53182.3b.

- ↑ Kristensen S (December 1992). "Spontaneous healing of traumatic tympanic membrane perforations in man: a century of experience". J Laryngol Otol. 106 (12): 1037–50. PMID 1487657. doi:10.1017/s0022215100121723.

- ↑ Lindeman P, Edström S, Granström G, Jacobsson S, von Sydow C, Westin T, Aberg B (December 1987). "Acute traumatic tympanic membrane perforations. Cover or observe?". Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 113 (12): 1285–7. PMID 3675893. doi:10.1001/archotol.1987.01860120031002.

- 1 2 Garth RJ (July 1995). "Blast injury of the ear: an overview and guide to management". Injury. 26 (6): 363–6. doi:10.1016/0020-1383(95)00042-8.

- 1 2 Smith N, Greinwald JR (2011). "To tube or not to tube: indications for myringotomy with tube placement". Current Opinion in Otolaryngology & Head and Neck Surgery. 19 (5): 363–366. PMID 21804383. doi:10.1097/MOO.0b013e3283499fa8.

- ↑ Langenheim, Johnny (18 September 2010). "The last of the sea nomads". The Guardian. Retrieved 15 February 2016.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Eardrum. |