Blood vessel

| Blood vessel | |

|---|---|

Simple diagram of the human circulatory system | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | vas sanguineum |

| TA | A12.0.00.001 |

| FMA | 63183 |

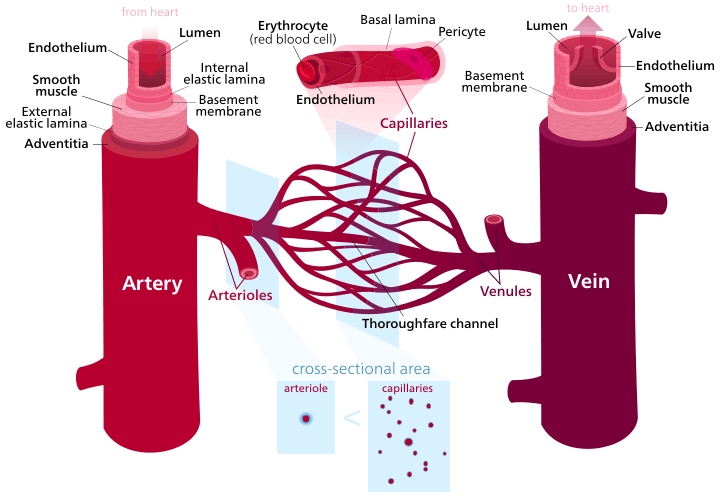

The blood vessels are the part of the circulatory system that transports blood throughout the human body.[1] There are three major types of blood vessels: the arteries, which carry the blood away from the heart; the capillaries, which enable the actual exchange of water and chemicals between the blood and the tissues; and the veins, which carry blood from the capillaries back toward the heart. The word vascular, meaning relating to the blood vessels, is derived from the Latin vas, meaning vessel. A few structures (such as cartilage and the lens of the eye) do not contain blood vessels and are labeled.

Structure

The arteries and veins have three layers, but the middle layer is thicker in the arteries than it is in the veins:

- Tunica intima (the thinnest layer): a single layer of simple squamous endothelial cells glued by a polysaccharide intercellular matrix, surrounded by a thin layer of subendothelial connective tissue interlaced with a number of circularly arranged elastic bands called the internal elastic lamina.

- Tunica media (the thickest layer in arteries): circularly arranged elastic fiber, connective tissue, polysaccharide substances, the second and third layer are separated by another thick elastic band called external elastic lamina. The tunica media may (especially in arteries) be rich in vascular smooth muscle, which controls the caliber of the vessel. Veins don't have the external elastic lamina, but only an internal one.

- Tunica adventitia: (the thickest layer in veins) entirely made of connective tissue. It also contains nerves that supply the vessel as well as nutrient capillaries (vasa vasorum) in the larger blood vessels.

Capillaries consist of little more than a layer of endothelium and occasional connective tissue.

When blood vessels connect to form a region of diffuse vascular supply it is called an anastomosis (pl. anastomoses). Anastomoses provide critical alternative routes for blood to flow in case of blockages.

There is a layer of muscle surrounding the arteries and the veins which help contract and expand the vessels. This creates enough pressure for blood to be pumped around the body. Blood vessels are part of the circulatory system, together with the heart and the blood.

Types

There are various kinds of blood vessels:

- Arteries

- Elastic arteries

- Distributing arteries

- Arterioles

- Capillaries (the smallest blood vessels)

- Venules

- Veins

- Large collecting vessels, such as the subclavian vein, the jugular vein, the renal vein and the iliac vein.

- Venae cavae (the two largest veins, carry blood into the heart).

They are roughly grouped as arterial and venous, determined by whether the blood in it is flowing away from (arterial) or toward (venous) the heart. The term "arterial blood" is nevertheless used to indicate blood high in oxygen, although the pulmonary artery carries "venous blood" and blood flowing in the pulmonary vein is rich in oxygen. This is because they are carrying the blood to and from the lungs, respectively, to be oxygenated.

Physiology

Blood vessels do not actively engage in the transport of blood (they have no appreciable peristalsis), but arteries—and veins to a degree—can regulate their inner diameter by contraction of the muscular layer. This changes the blood flow to downstream organs, and is determined by the autonomic nervous system. Vasodilation and vasoconstriction are also used antagonistically as methods of thermoregulation.

Oxygen (bound to hemoglobin in red blood cells) is the most critical nutrient carried by the blood. In all arteries apart from the pulmonary artery, hemoglobin is highly saturated (95-100%) with oxygen. In all veins apart from the pulmonary vein, the hemoglobin is desaturated at about 75%. (The values are reversed in the pulmonary circulation.)

The blood pressure in blood vessels is traditionally expressed in millimetres of mercury (1 mmHg = 133 Pa). In the arterial system, this is usually around 120 mmHg systolic (high pressure wave due to contraction of the heart) and 80 mmHg diastolic (low pressure wave). In contrast, pressures in the venous system are constant and rarely exceed 10 mmHg.

Vasoconstriction is the constriction of blood vessels (narrowing, becoming smaller in cross-sectional area) by contracting the vascular smooth muscle in the vessel walls. It is regulated by vasoconstrictors (agents that cause vasoconstriction). These include paracrine factors (e.g. prostaglandins), a number of hormones (e.g. vasopressin and angiotensin) and neurotransmitters (e.g. epinephrine) from the nervous system.

Vasodilation is a similar process mediated by antagonistically acting mediators. The most prominent vasodilator is nitric oxide (termed endothelium-derived relaxing factor for this reason).

Permeability of the endothelium is pivotal in the release of nutrients to the tissue. It is also increased in inflammation in response to histamine, prostaglandins and interleukins, which leads to most of the symptoms of inflammation (swelling, redness, warmth and pain).

Factors affecting blood flow resistance

Resistance occurs where the vessels away from the heart oppose the flow of blood. Resistance is an accumulation of three different factors: blood viscosity, blood vessel length, and vessel radius.[2]

Blood viscosity is the thickness of the blood and its resistance to flow as a result of the different components of the blood. Blood is 92% water by weight and the rest of blood is composed of protein, nutrients, electrolytes, wastes, and dissolved gases. Depending on the health of an individual, the blood viscosity can vary (i.e. anemia causing relatively lower concentrations of protein, high blood pressure an increase in dissolved salts or lipids, etc.).[2]

Vessel length is the total length of the vessel measured as the distance away from the heart. As the total length of the vessel increases, the total resistance as a result of friction will increase.[2]

Vessel radius also affects the total resistance as a result of contact with the vessel wall. As the radius of the wall gets smaller, the proportion of the blood making contact with the wall will increase. The greater amount of contact with the wall will increase the total resistance against the blood flow.[3]

Disease

Blood vessels play a huge role in virtually every medical condition. Cancer, for example, cannot progress unless the tumor causes angiogenesis (formation of new blood vessels) to supply the malignant cells' metabolic demand. Atherosclerosis, the formation of lipid lumps (atheromas) in the blood vessel wall, is the most common cardiovascular disease, the main cause of death in the Western world.[4]

Blood vessel permeability is increased in inflammation. Damage, due to trauma or spontaneously, may lead to hemorrhage due to mechanical damage to the vessel endothelium. In contrast, occlusion of the blood vessel by atherosclerotic plaque, by an embolised blood clot or a foreign body leads to downstream ischemia (insufficient blood supply) and possibly necrosis. Vessel occlusion tends to be a positive feedback system; an occluded vessel creates eddies in the normally laminar flow or plug flow blood currents. These eddies create abnormal fluid velocity gradients which push blood elements such as cholesterol or chylomicron bodies to the endothelium. These deposit onto the arterial walls which are already partially occluded and build upon the blockage.[5]

Vasculitis is inflammation of the vessel wall, due to autoimmune disease or infection.

References

- ↑ "Blood Vessels - Heart and Blood Vessel Disorders - Merck Manuals Consumer Version". Merck Manuals Consumer Version. Retrieved 2016-12-22.

- 1 2 3 Anatomy Physiology: The Unity of Form and Function, Saladin, McGraw Hill, 2012

- ↑ "Factors that Affect Blood Pressure" (PDF). Retrieved 6 Dec 2014.

- ↑ "Nerves and blood vessels". 420evaluationsonline. Retrieved 2 August 2016.

- ↑ Multiphase Flow and Fluidization, Gidaspow et al., Academic Press, 1992