Ulysses (spacecraft)

|

Artist rendering of Ulysses spacecraft in the inner Solar System | |

| Operator | NASA / ESA |

|---|---|

| COSPAR ID | 1990-090B |

| SATCAT no. | 20842 |

| Website |

NASA Page ESA Page |

| Mission duration | 18 years, 8 months and 24 days |

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Launch mass | 370 kg (820 lb) |

| Power | 285 W |

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | 11:47:16, October 6, 1990 |

| Rocket | Space Shuttle Discovery (STS-41) with Inertial Upper Stage and PAM-S |

| Launch site | KSC Launch Complex 39B |

| End of mission | |

| Disposal | Decommissioned |

| Deactivated | June 30, 2009 |

| Orbital parameters | |

| Reference system | Heliocentric |

| Eccentricity | 0.60262 |

| Perihelion | 1.35 AU |

| Apohelion | 5.4 AU |

| Inclination | 79.11° |

| Period | 2,264.26 days (6.2 years) |

| Epoch | 12:00:00, February 24, 1992 |

| Flyby of Jupiter (gravity assist) | |

| Closest approach | February 08, 1992 |

| Distance | 6.3 Jupiter Radii (279,865 mi) |

ESA solar system insignia for the Ulysses mission | |

Ulysses is a decommissioned robotic space probe whose primary mission was to orbit the Sun and study it at all latitudes. It was launched in 1990, made three "fast latitude scans" of the Sun in 1994/1995, 2000/2001, and 2007/2008. In addition, the probe studied several comets. Ulysses was a joint venture of NASA and the European Space Agency (ESA) with participation from Canada's National Research Council.[1] The last day for mission operations on Ulysses was June 30, 2009.[2][3]

To study the Sun at all latitudes the probe needed to change its orbital inclination and leave the plane of the Solar System – to change the orbital inclination of a spacecraft a large change in heliocentric velocity is needed. However the necessary amount of velocity change to achieve a high inclination orbit of about 80° far exceeded the capabilities of any launch vehicle. Therefore, to reach the desired orbit around the Sun a gravity assist manoeuvre around Jupiter was chosen, but this Jupiter encounter meant that Ulysses could not be powered by solar cells – the probe instead was powered by a radioisotope thermoelectric generator (RTG).

The spacecraft was originally named Odysseus, because of its lengthy and indirect trajectory to study the solar poles. It was renamed Ulysses, the Latin translation of "Odysseus", at ESA's request in honour not only of Homer's mythological hero but also with reference to Dante's description in Dante's Inferno.[4] Ulysses was originally scheduled for launch in May 1986 aboard the Space Shuttle Challenger on STS-61-F. Due to the loss of Challenger, the launch of Ulysses was delayed until October 6, 1990 aboard Discovery (mission STS-41).

Spacecraft

The spacecraft body was roughly a box, approximately 3.2 × 3.3 × 2.1 m (10.5 x 10.8 x 6.9 ft) in size. The box mounted the 1.65 m (5.4 ft) dish antenna and the GPHS-RTG radioisotope thermoelectric generator (RTG) power source. The box was divided into noisy and quiet sections. The noisy section abutted the RTG; the quiet section housed the instrument electronics. Particularly "loud" components, such as the preamps for the radio dipole, were mounted outside the structure entirely, and the box acted as a Faraday cage.

Ulysses was spin-stabilised about its z-axis which roughly coincides with the axis of the dish antenna. The RTG, whip antennas, and instrument boom were placed to stabilize this axis, with the spin rate nominally at 5 rpm. Inside the body was a hydrazine fuel tank. Hydrazine monopropellant was used for course corrections inbound to Jupiter, and later used exclusively to repoint the spin axis (and thus, the antenna) at Earth. The spacecraft was controlled by eight thrusters in two blocks. Thrusters were pulsed in the time domain to perform rotation or translation. Four Sun sensors detected orientation. For fine attitude control, the S-band antenna feed was mounted slightly off-axis. This offset feed combined with the spacecraft spin introduced an oscillation to an S-band radio signal transmitted from Earth when received on board the spacecraft. The amplitude and phase of this oscillation was proportional to the orientation of the spin axis relative to the Earth direction. This method of determining the relative orientation is called CONSCAN and was used by early radars for automated tracking of targets and also very common in early infra-red guided missiles.

The spacecraft used S-band for uplinked commands and downlinked telemetry, through dual redundant 5-watt transceivers. The spacecraft used X-band for science return (downlink only), using dual 20 W TWTAs until the failure of the last remaining TWTA in January 2008. Both bands used the dish antenna with prime-focus feeds, unlike the Cassegrain feeds of most other spacecraft dishes.

Dual tape recorders, each of approximately 45-megabit capacity, stored science data between the nominal eight-hour communications sessions during the prime and extended mission phases.

The spacecraft was designed to withstand both the heat of the inner Solar System and the cold at Jupiter's distance. Extensive blanketing and electric heaters protected the probe against the cold temperatures of the outer Solar System.

Multiple computer systems (CPUs/microprocessors/Data Processing Units) are used in several of the scientific instruments, including several radiation-hardened RCA CDP1802 microprocessors. Documented 1802 usage includes dual-redundant 1802s in the COSPIN, and at least one 1802 each in the GRB, HI-SCALE, SWICS, SWOOPS and URAP instruments, with other possible microprocessors incorporated elsewhere.[5]

Total mass at launch was 366.7 kg (808 lb), of which 33.5 kg (73.9 lb) was hydrazine (used for attitude control and orbit correction).

Instruments

Radio/Plasma antennas. Two beryllium-copper antennas unreeled outwards from the body, perpendicular to the RTG and spin axis. Together this dipole spanned 72 meters (236.2 ft). A third antenna, of hollow beryllium-copper, deployed from the body, along the spin axis opposite the dish. It was a monopole antenna, 7.5 meters (24.6 ft) long. These measured radio waves generated by plasma releases, or the plasma itself as it passed over the spacecraft. This receiver ensemble was sensitive from dc to 1 MHz.[6]

Experiment Boom. A third type of boom, shorter and much more rigid, extended from the last side of the spacecraft, opposite the RTG. This was a hollow carbon-fiber tube, of 50 mm (2 in.) diameter. It can be seen in the photo as the silver rod stowed alongside the body. It carried four types of instruments. A solid-state X-ray instrument, which was composed of two silicon detectors to study X-rays from solar flares and Jupiter's aurorae. The GRB experiment consisted of two CsI scintillator crystals with photomultipliers. Two different magnetometers were mounted: a vector helium magnetometer and a fluxgate magnetometer. A two axis magnetic search coil antenna measured AC magnetic fields.

Body-Mounted Instruments. Detectors for electrons, ions, neutral gas, dust, and cosmic rays were mounted on the spacecraft body around the quiet section.

- SWOOPS (Solar Wind Observations Over the Poles of the Sun) measures positive ions and electrons.[7]

Lastly, the radio communications link could be used to search for gravitational waves[8] (through Doppler shifts) and to probe the Sun's atmosphere through radio occultation. No gravitational waves were detected.

Total instrument mass is 55 kg (121.3 lb).

Mission

Planning

Until Ulysses, the Sun was only observed from low solar latitudes. The Earth's orbit defines the ecliptic plane, which differs from the Sun's equatorial plane by only 7.25 degrees. Even spacecraft directly orbiting the Sun do so in planes close to the ecliptic because a direct launch into a high-inclination solar orbit would require a prohibitively large launch vehicle.

Several spacecraft (Mariner 10, Pioneer 11, and Voyagers 1 and 2) had performed gravity assist manoeuvres in the 1970s. Those manoeuvres were to reach other planets also orbiting close to the ecliptic, so they were mostly in-plane changes. However, gravity assists are not limited to in-plane maneuvers; a suitable flyby of Jupiter could produce a significant plane change. An Out-Of-The-Ecliptic mission (OOE) was thereby proposed. See article Pioneer H.

Originally, two spacecraft were to be built by NASA and ESA, as the International Solar Polar Mission. One would be sent over Jupiter, then under the Sun. The other would fly under Jupiter, then over the Sun. This would provide simultaneous coverage. Due to cutbacks, the US spacecraft was canceled in 1981. One spacecraft was designed, and the project recast as Ulysses, due to the indirect and untried flight path. NASA would provide the Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generator (RTG) and launch services, ESA would build the spacecraft assigned to Astrium GmbH, Friedrichshafen, Germany (formerly Dornier Systems). The instruments would be split into teams from universities and research institutes in Europe and the United States. This process provided the 10 instruments on board.

The changes delayed launch from February 1983 to May 1986 where it was to be deployed by the Space Shuttle Challenger, however, the Challenger disaster pushed the date to October 1990.

Launch

Ulysses was deployed into low-Earth orbit from the Space Shuttle Discovery. From there, it was propelled on a trajectory to Jupiter by a combination of solid rocket motors.[9] This upper stage consisted of a two-stage Boeing IUS (Inertial Upper Stage), plus a McDonnell Douglas PAM-S (Payload Assist Module-Special). The IUS was inertially stabilised and actively guided during its burn. The PAM-S was unguided and it and Ulysses were spun up to 80 rpm for stability at the start of its burn. On burnout of the PAM-S, the motor and spacecraft stack was yo-yo de-spun (weights deployed at the end of cables) to below 8 rpm prior to separation of the spacecraft. On leaving Earth, the spacecraft became the fastest ever artificially-accelerated object, and held that title until the New Horizons probe was launched.

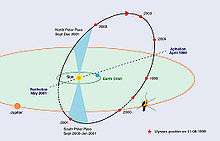

On its way to Jupiter the spacecraft was in an elliptical non-Hohmann transfer orbit. At this time Ulysses had a low orbital inclination to the ecliptic.

Jupiter swing-by

It arrived at Jupiter on 8 February 1992 for a swing-by maneuver that increased its inclination to the ecliptic by 80.2 degrees. The giant planet's gravity bent the spacecraft's flight path southward and away from the ecliptic plane. This put it into a final orbit around the Sun that would take it past the Sun's north and south poles. The size and shape of the orbit were adjusted to a much smaller degree so that aphelion remained at approximately 5 AU, Jupiter's distance from the Sun, and perihelion was somewhat greater than 1 AU, the Earth's distance from the Sun. The orbital period is approximately six years.

On November 4th 2098 Ulysses will do another slingshot at Jupiter which will raise its apoapsis beyond the orbit of Neptune.

Polar regions of the Sun

Between 1994 and 1995 it explored both the southern and northern polar regions of the Sun, respectively.

Comet C/1996 B2 (Hyakutake)

On May 1, 1996, the spacecraft unexpectedly crossed the ion tail of Comet Hyakutake (C/1996 B2), revealing the tail to be at least 3.8 AU in length.[10][11]

Comet C/1999 T1 (McNaught–Hartley)

An encounter with a comet tail happened again in 1999 when Ulysses flew through the ion tailings of C/1999 T1 (McNaught-Hartley). A coronal mass ejection carried the cometary material to Ulysses.[11][12]

Comet C/2000 S5

Second Jupiter encounter

Ulysses approached aphelion in 2003/2004 and made further distant observations of Jupiter.[13]

Comet C/2006 P1 (McNaught)

In 2007 Ulysses passed through the tail of comet C/2006 P1 (McNaught). The results were surprisingly different from its pass through Hyakutake's tail, with the measured solar wind velocity dropping from approximately 700 kilometers per second (1565.9 mph) to less than 400 kilometers per second (894.8 mph).[14]

Extended mission

ESA's Science Program Committee approved the fourth extension of the Ulysses mission to March 2009[15] thereby allowing it to operate over the Sun's poles for the third time in 2007 and 2008. After it became clear that the power output from the spacecraft's RTG would be insufficient to operate science instruments and keep the attitude control fuel, hydrazine, from freezing, instrument power sharing was initiated. Up until then, the most important instruments had been kept online constantly, whilst others were deactivated. When the probe neared the Sun, its power-hungry heaters were turned off and all instruments were turned on.[16]

On February 22, 2008, 17 years and 4 months after the launch of the spacecraft, ESA and NASA announced that the mission operations for Ulysses would likely cease within a few months.[17][18] On April 12, 2008 NASA announced that the end date will be July 1, 2008.[19]

The spacecraft operated successfully for over four times its design life. A component within the last remaining working chain of X-band downlink subsystem failed on January 15, 2008. The other chain in the X-band subsystem had previously failed in 2003.[20]

Downlink to Earth resumed on S-band, but the beamwidth of the high gain antenna in the S-band was not as narrow as in the X–band, so that the received downlink signal was much weaker, hence reducing the achievable data rate. As the spacecraft traveled on its outbound trajectory to the orbit of Jupiter, the downlink signal would have eventually fallen below the receiving capability of even the largest antennas (70 meters - 229.7 feet - in diameter) of the Deep Space Network.

Even before the downlink signal was lost due to distance, the hydrazine attitude control fuel on board the spacecraft was considered likely to freeze, as the radioisotope thermal generators (RTGs) failed to generate enough power for the heaters to overcome radiative heat loss into space. Once the hydrazine froze, the spacecraft would no longer be able to maneuver to keep its high gain antenna pointing towards Earth, and the downlink signal would then be lost in a matter of days. The failure of the X-band communications subsystem hastened this, because the coldest part of the fuel pipework was routed over the X-band TWTAs, because when one of them was operating, this kept this part of the pipework warm enough.

The previously announced mission end date of July 1, 2008, came and went but mission operations continued albeit in a reduced capacity. The availability of science data gathering was limited to only when Ulysses was in contact with a ground station due to the deteriorating S-band downlink margin no longer being able to support simultaneous real-time data and tape recorder playback.[21] When the spacecraft was out of contact with a ground station, the S-band transmitter was switched off and the power was diverted to the internal heaters to add to the warming of the hydrazine. On June 30, 2009, ground controllers sent commands to switch to the low gain antennas. This stopped communications with the spacecraft, in combination with previous the commands to set the shut down of its transmitter entirely.[2][22]

Results

During cruise phases, Ulysses provided unique data. As the only spacecraft out of the ecliptic with a gamma-ray instrument, Ulysses was an important part of the InterPlanetary Network (IPN). The IPN detects gamma ray bursts (GRBs); since gamma rays cannot be focused with mirrors, it was very difficult to locate GRBs with enough accuracy to study them further. Instead, several spacecraft can locate the burst through triangulation (or, more specifically, multilateration). Each spacecraft has a gamma-ray detector, with readouts noted in tiny fractions of a second. By comparing the arrival times of gamma showers with the separations of the spacecraft, a location can be determined, for follow-up with other telescopes. Because gamma rays travel at the speed of light, wide separations are needed. Typically, a determination came from comparing: one of several spacecraft orbiting the Earth, an inner-Solar-system probe (to Mars, Venus, or an asteroid), and Ulysses. When Ulysses crossed the ecliptic twice per orbit, many GRB determinations lost accuracy.

Additional discoveries:[23]

- Data provided by Ulysses led to the discovery that the Sun's magnetic field interacts with the Solar System in a more complex fashion than previously assumed.

- Data provided by Ulysses led to the discovery that dust coming into the Solar System from deep space was 30 times more abundant than previously expected.

- In 2007–2008 data provided by Ulysses led to the determination that the magnetic field emanating from the Sun's poles is much weaker than previously observed.

- That the solar wind has "grown progressively weaker during the mission and is currently at its weakest since the start of the Space Age."[22]

See also

- Advanced Composition Explorer

- List of missions to the outer planets

- Solar and Heliospheric Observatory

- WIND spacecraft

References

- ↑ "Welcome to the HIA Ulysses Project". Herzberg Institute of Astrophysics. Archived from the original on 17 August 2011.

The Herzberg Institute of Astrophysics (HIA) of the National Research Council of Canada provided instrumentation and test equipment for the COsmic ray and Solar Particle INvestigation (COSPIN) on the Ulysses spacecraft. The COSPIN instrument consists of five sensors which measure energetic nucleons and electrons over a wide range of energies. This was the first participation by Canada in a deep-space interplanetary mission.

- 1 2 "Ulysses: 12 extra months of valuable science". European Space Agency. 30 June 2009. Retrieved 2009-07-01.

- ↑ The odyssey concludes ...

- ↑ "Inferno of Ulysses' urge to explore an uninhabited world behind the Sun. In Jane's Spaceflight Directory 1988, ISBN 0-7106-0860-8

- ↑ Ulysses NASA Documentation Archive

- ↑ Unified Radio and Plasma Wave Investigation, JPL

- ↑ Goldstein, Bruce. SWOOPS/Electron – User Notes, Jet Propulsion Laboratory

- ↑ The Gravity Wave Experiment, Astronomy and Astrophysics

- ↑ ESA—Space Science—Sun to set on Ulysses solar mission on 1 July

- ↑ Jones GH; Balogh A; Horbury TS (2000). "Identification of comet Hyakutake's extremely long ion tail from magnetic field signatures". Nature. 404 (6778): 574–6. Bibcode:2000Natur.404..574J. PMID 10766233. doi:10.1038/35007011.

- 1 2 3 Ulysses Catches Another Comet by the Tail

- 1 2 G. Gloeckler et al. Cometary Ions Trapped in a Coronal Mass Ejection

- ↑ Ulysses - Science - Jupiter Distant Encounter Selected References

- ↑ Neugebauer, Gloeckle; et al. (October 1, 2007). "Encounter of the Ulysses Spacecraft with the Ion Tail of Comet McNaught". The Astrophysical Journal. 667 (2): 1262–1266. Bibcode:2007ApJ...667.1262N. doi:10.1086/521019.

- ↑ ESA Science & Technology: Ulysses Mission Extended

- ↑ ESA Portal – Ulysses scores a hat-trick

- ↑ "Ulysses mission coming to a natural end". European Space Agency. 2008-02-22. Retrieved 2008-02-23.

- ↑ "International Solar Mission to End Following Stellar Performance". NASA. 2008-02-22. Retrieved 2008-02-23.

- ↑ https://news.yahoo.com/s/ap/20080612/ap_on_sc/sci_solar_probe

- ↑ "February 2003 Operations". European Space Agency.

- ↑ Ulysses Mission Ops—No more data playback

- 1 2 "Ulysses Spacecraft Ends Historic Mission of Discovery". June 30, 2009. Retrieved 2009-07-01.

- ↑ NASA : International Mission Studying Sun to Conclude

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ulysses (spacecraft). |

| Wikinews has related news: Ulysses spacecraft retires after 17 year mission |

- ESA Ulysses website

- ESA Ulysses mission operations website

- ESA Ulysses Home page

- NASA/JPL Ulysses website

- Ulysses Measuring Mission Profile by NASA's Solar System Exploration

- ESA/NASA/JPL: Ulysses subsystems and instrumentation in high detail

- Where is Ulysses' now!

- Max Planck Institute Ulysses website

- Interview with Ulysses Mission Operations Manager Nigel Angold on Planetary Radio