United Kingdom general election, 1979

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

All 635 seats in the House of Commons 318 seats needed for a majority | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Turnout |

76.0% ( | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

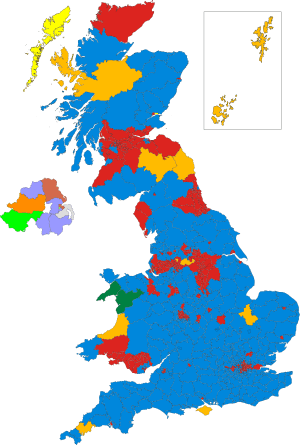

Colours denote the winning party, as shown in the main table of results. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The United Kingdom general election of 1979 was held on 3 May 1979 to elect 635 members to the British House of Commons. The Conservative Party, led by Margaret Thatcher, ousted the incumbent Labour government of James Callaghan with a parliamentary majority of 43 seats. The election was the first of four consecutive election victories for the Conservative Party, and Thatcher became the United Kingdom's and Europe's first elected female head of government.

The previous parliamentary term had begun in October 1974, when Harold Wilson led Labour to a majority of three seats, but within 18 months he had resigned as prime minister to be succeeded by James Callaghan, and within a year the government's narrow parliamentary majority had gone. Callaghan had made agreements with the Liberals, the Ulster Unionists, as well as the Scottish and Welsh nationalists in order to remain in power. However, on 28 March 1979 following the defeat of the Scottish devolution referendum, Thatcher tabled a motion of no confidence in James Callaghan's Labour government, which was passed by just one vote (311 to 310), triggering a general election five months before the end of the government's term.

The Labour campaign was hampered by the series of industrial disputes and strikes during the Winter of 1978-79, known as the Winter of Discontent and the party focused its campaign on support for the National Health Service and full employment. After intense media speculation, Callaghan had announced early in the autumn of 1978 that a general election would not take place that year having received private polling data which suggested a parliamentary majority was unlikely.[1]

The Conservative campaign employed the advertising agency Saatchi & Saatchi and pledged to control inflation as well as curbing the power of the trade unions. The Liberal Party was damaged by allegations that its former leader Jeremy Thorpe had been involved in a homosexual affair, and had conspired to murder his former lover. The Liberals were now being led by David Steel, meaning that all three major parties entered the election with a new leader.

The election saw a 5.2% swing from Labour to the Conservatives, the largest swing since the 1945 election, which Clement Attlee won for Labour. Margaret Thatcher became Prime Minister, and Callaghan was replaced as Labour leader by Michael Foot in 1980. Results for the election were broadcast live on the BBC, and presented by David Dimbleby and Robin Day, with Robert McKenzie on the 'Swingometer', and further analysis provided by David Butler.[2] It was the first general election to feature Rick Wakeman's song Arthur on the BBC's coverage.

Future Prime Minister John Major entered Parliament in this election. Jeremy Thorpe, Shirley Williams and Barbara Castle all left Parliament as a result of this election.

Timeline

After suffering a vote of no confidence on 28 March 1979, the Prime Minister James Callaghan was forced to announce that he would request a dissolution of Parliament to onset a general election. The key dates were as follows:

| Saturday 7 April | Dissolution of the 47th parliament and campaigning officially begins; 2,576 candidates enter to contest 635 seats |

| Wednesday 2 May | Campaigning officially ends |

| Thursday 3 May | Polling day |

| Friday 4 May | The Conservative Party wins power with a majority of 43 |

| Wednesday 9 May | The 48th parliament assembles |

| Tuesday 15 May | State Opening of Parliament |

Background

Britain's economy during the 1970s was so weak that Labour minister James Callaghan warned his fellow Cabinet members in 1974 of the possibility of "a breakdown of democracy", telling them, "If I were a young man, I would emigrate."[3] Callaghan succeeded Harold Wilson as Labour Prime Minister after the latter's surprise resignation in April 1976. By March 1977 Labour had become a minority government after several by-election defeats, and from March 1977 to August 1978 Callaghan governed by an agreement with the Liberal Party through the Lib-Lab pact. Callaghan had considered calling an election in the autumn of 1978,[4] but ultimately decided that imminent tax cuts, and a possible economic upturn in 1979, could favour his party at the polls by holding the election later. Although published opinion polls suggested that he might win,[5] private polls commissioned by the Labour Party from MORI had suggested the two main parties had much the same level of support.[1]

However, events would soon overtake the Labour government. A series of industrial disputes in the winter of 1978–79, dubbed the "Winter of Discontent", led to widespread strikes across the country and seriously hurt Labour's standings in the polls. When the Scottish National Party (SNP) withdrew support for the Scotland Act 1978, a vote of no confidence was held and passed by one vote on 28 March 1979, forcing Callaghan to call a general election. As the previous election had been held in October 1974, Labour could have held on until the autumn of 1979 if it had not been for the lost confidence vote.

Margaret Thatcher had won her party's 1975 leadership election over former leader Edward Heath.

David Steel had replaced Jeremy Thorpe as leader of the Liberal Party in 1976, after allegations of homosexuality and conspiracy to murder his former lover forced Thorpe to resign. The Thorpe affair led to a fall in the Liberal vote after what was thought to be a breakthrough in the February 1974 election.

Campaign

This was the first election since 1959 to feature three new leaders for the main political parties. The three main parties all advocated cutting income tax. Labour and the Conservatives did not specify the exact thresholds of income tax they would implement but the Liberals did, claiming they would have income tax starting at 20% with a top rate of 50%.[6]

Without explicitly mentioning Thatcher's sex, Callaghan was (as Christian Caryl later wrote) "a master at sardonically implying that whatever the leader of the opposition said was made even sillier by the fact that it was said by a woman". Thatcher used the tactics that had defeated her other male opponents: Constantly studying, sleeping only a few hours a night, and exploiting her femininity to appear as someone who understood housewives' household budgets.[7]

Labour

The Labour campaign reiterated their support for the National Health Service and full employment and focused on the damage they believed the Conservatives would do to the country. In an early campaign broadcast, Callaghan asked: "The question you will have to consider is whether we risk tearing everything up by the roots". Towards the end of Labour's campaign Callaghan claimed a Conservative government "would sit back and just allow firms to go bankrupt and jobs to be lost in the middle of a world recession" and that the Conservatives were "too big a gamble to take".[8]

The Labour Party manifesto "The Labour way is the better way", was issued on 6 April. Callaghan presented four priorities:

- (i) "We must keep a curb on 'inflation and prices";

- (ii) "we will carry forward the task of putting into practice the new framework to improve industrial relations that we have hammered out with the TUC"

- (iii) "we give a high priority to working for a return to full employment";

- (iv) "we are deeply concerned to enlarge people's freedom"; and "we will use Britain's influence to strengthen world peace and defeat world poverty".

Conservatives

The Conservatives campaigned on economic issues, pledging to control inflation and to reduce the increasing power of the trade unions who supported the mass strikes. They also employed the advertising agency Saatchi & Saatchi who created the Labour Isn't Working poster. The Conservative campaign was focused on gaining support from traditional Labour voters who had never voted Conservative before, first-time voters, and people who had voted Liberal in 1974.[9] Thatcher's advisers, Gordon Reece and Timothy Bell, co-ordinated their presentation with the editor of The Sun, Larry Lamb. The Sun printed a series of articles by disillusioned former Labour ministers (Reginald Prentice, Richard Marsh, Lord George-Brown, Alfred Robens and Lord Chalfont) detailing why they had switched their support to Thatcher. She explicitly asked Labour voters for their support when she launched her campaign in Cardiff, claiming that Labour was now extreme.[10] Choosing to start her campaign in the strongly Labour-supporting city was part of Thatcher's strategy of appealing to C2 skilled laborers that both parties had previously seen as certain Labour voters; she thought that many would support her promises to reduce unions' power and enact the right to buy their homes.[7]

The Conservative Manifesto, drafted by Chris Patten and Adam Ridley and edited by Angus Maude, reflected Thatcher's views and was issued on 11 April.[11] It promised five major policies:

- "(i) to restore the health of our economic and social life, by controlling inflation and striking a fair balance between the rights and duties of the trade union movement;

- (ii) to restore incentives so that hard work pays, success is rewarded and genuine new jobs are created in an expanding economy;

- (iii) to uphold Parliament and the rule of law;

- (iv) to support family life, by helping people to become home-owners, raising the standards of their children's education and concentrating welfare services on the effective support of the old, the sick, the disabled and those who are in real need; and

- (v) to strengthen Britain's defences and work with our allies to protect our interests in an increasingly threatening world."[12]

An analysis of the election showed that the Conservatives gained an 11% swing among the skilled working-class (the C2s) and a 9% swing amongst the unskilled working class (the DEs).[13]

Results

In the end, the overall swing of 5.2% was the largest since 1945 and gave the Conservatives a workable majority of 43 for the country's first female Prime Minister. The Conservative victory in 1979 also marked a change in government which would continue for 18 years until the Labour victory in 1997. The SNP saw a massive collapse in support, losing nine of their 11 MPs. The Liberals had a disappointing election; their scandal-hit former leader Jeremy Thorpe lost his seat in North Devon to the Conservatives.

This was the last election as of 2017 in which the Conservatives recorded at least 30% of the vote in Scotland. The Tories did manage to hold most of their Scottish seats in 1983 before going into decline thereafter.

| 339 | 269 | 11 | 16 |

| Conservative | Labour | Lib | O |

| Candidates | Votes | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Leader | Standing | Elected | Gained | Unseated | Net | % of total | % | No. | Net % | |

| Conservative | Margaret Thatcher | 622 | 339 | 63 | 1 | + 62 | 53.4% | 43.9 | 13,697,923 | + 8.1 | |

| Labour | James Callaghan | 623 | 269 | 4 | 54 | - 50 | 42.4% | 36.9 | 11,532,218 | - 2.3 | |

| Liberal | David Steel | 577 | 11 | 1 | 3 | - 2 | 1.7% | 13.8 | 4,313,804 | - 4.5 | |

| SNP | William Wolfe | 71 | 2 | 0 | 9 | - 9 | 0.31% | 1.6 | 504,259 | - 1.3 | |

| UUP | Harry West | 11 | 5 | 1 | 2 | - 1 | 0.79% | 0.8 | 254,578 | - 0.1 | |

| National Front | John Tyndall | 303 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | N/A | 0.6 | 191,719 | + 0.2 | |

| Plaid Cymru | Gwynfor Evans | 36 | 2 | 0 | 1 | - 1 | 0.31% | 0.4 | 132,544 | - 0.2 | |

| SDLP | John Hume | 9 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.16% | 0.4 | 126,325 | - 0.2 | |

| Alliance | Oliver Napier | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | N/A | 0.3 | 82,892 | + 0.1 | |

| DUP | Ian Paisley | 5 | 3 | 2 | 0 | + 2 | 0.47% | 0.2 | 70,795 | - 0.1 | |

| Ecology | Jonathan Tyler | 53 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | N/A | 0.1 | 39,918 | + 0.1 | |

| UUUP | Ernest Baird | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | + 1 | 0.16% | 0.1 | 39,856 | N/A | |

| Ulster Popular Unionist | James Kilfedder | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | + 1 | 0.16% | 0.1 | 36,989 | + 0.1 | |

| Independent Labour | N/A | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | N/A | 0.1 | 26,058 | - 0.1 | |

| Irish Independence | Fergus McAteer and Frank McManus | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | N/A | 0.1 | 23,086 | N/A | |

| Independent Republican | N/A | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | N/A | 0.1 | 22,398 | - 0.1 | |

| Independent | N/A | 62 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | N/A | 0.1 | 19,531 | + 0.1 | |

| Communist | Gordon McLennan | 38 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | N/A | 0.1 | 16,858 | 0.0 | |

| SLP | Jim Sillars | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | N/A | 0.1 | 13,737 | N/A | |

| Workers Revolutionary | Michael Banda | 60 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | N/A | 0.1 | 12,631 | + 0.1 | |

| Workers' Party | Tomás Mac Giolla | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | N/A | 0.1 | 12,098 | 0.0 | |

| Independent SDLP | N/A | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | N/A | 0.0 | 10,785 | N/A | |

| Unionist Party NI | Anne Dickson | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | N/A | 0.0 | 8,021 | - 0.1 | |

| Independent Conservative | N/A | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | N/A | 0.0 | 4,841 | 0.0 | |

| NI Labour | Alan Carr | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | N/A | 0.0 | 4,441 | 0.0 | |

| Mebyon Kernow | Richard Jenkin | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | N/A | 0.0 | 4,164 | 0.0 | |

| Democratic Labour | Dick Taverne | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | N/A | 0.0 | 3,785 | - 0.1 | |

| Wessex Regionalist | Viscount Weymouth | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | N/A | 0.0 | 3,090 | N/A | |

| Socialist Unity | None | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | N/A | 0.0 | 2,834 | N/A | |

| United Labour | Paddy Devlin | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | N/A | 0.0 | 1,895 | N/A | |

| Independent Democratic | N/A | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | N/A | 0.0 | 1,087 | N/A | |

| United Country | Edmund Iremonger | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | N/A | 0.0 | 1,033 | N/A | |

| Independent Liberal | N/A | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | N/A | 0.0 | 1,023 | 0.0 | |

| Independent Socialist | N/A | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | N/A | 0.0 | 770 | 0.0 | |

| Workers (Leninist) | Royston Bull | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | N/A | 0.0 | 767 | 0.0 | |

| New Britain | Dennis Delderfield | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | N/A | 0.0 | 717 | 0.0 | |

| Fellowship | Ronald Mallone | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | N/A | 0.0 | 531 | 0.0 | |

| More Prosperous Britain | Tom Keen | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | N/A | 0.0 | 518 | 0.0 | |

| United English National | John Kynaston | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | N/A | 0.0 | 238 | 0.0 | |

| Cornish Nationalist | James Whetter | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | N/A | 0.0 | 227 | N/A | |

| Social Democrat | Donald Kean | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | N/A | 0.0 | 144 | 0.0 | |

| English National | Frank Hansford-Miller | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | N/A | 0.0 | 142 | 0.0 | |

| The Dog Lovers' Party | Auberon Waugh | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | N/A | 0.0 | 79 | 0.0 | |

| Socialist (GB) | None | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | N/A | 0.0 | 78 | 0.0 | |

All parties shown.

| Government's new majority | 43 |

| Total votes cast | 31,221,362 |

| Turnout | 76% |

N.B. The Vanguard Progressive Unionist Party had folded in 1978. Of its three MPs, two joined the Ulster Unionist Party (one held his seat, the other lost to the Democratic Unionist Party) and the third defended and held his seat for the United Ulster Unionist Party.

James Kilfedder had been previously elected as an Ulster Unionist MP, but left the party, defending and holding his seat as an Independent Ulster Unionist. He subsequently founded the Ulster Popular Unionist Party but did not use that label in this election.

Votes summary

Seats summary

Incumbents defeated

Conservative

- Teddy Taylor (Glasgow Cathcart)

- Andrew MacKay (Birmingham Stechford) - By-election win

- Richard Page (Workington) - By-election win

- Tim Smith (Ashfield) - By-election win

- Robin Hodgson (Walsall North) - By-election win

Labour

- Geoffrey Edge (Aldridge-Brownhills)

- Eric Moonman (Basildon)

- Alfred Bates (Bebington and Ellesmere Port)

- Roderick MacFarquhar (Belper)

- Raymond Carter (Birmingham Northfield) - Minister of State in the Northern Ireland Office

- Tom Litterick (Birmingham Selly Oak)

- Syd Tierney (Birmingham Yardley) - President of the Union of Shop, Distributive and Allied Workers

- Caerwyn Roderick (Brecon & Radnor)

- Ronald Thomas (Bristol North West)

- George Rodgers (Chorley)

- Sydney Irving (Dartford)

- William Molloy (Ealing North)

- Bryan Davies (Enfield North)

- John Watkinson (Gloucestershire West)

- John Ovenden (Gravesend)

- Alan Lee Williams (Hornchurch) - Parliamentary Private Secretary to Roy Mason

- Shirley Williams (Hertford and Stevenage) - Secretary of State for Education and Science

- Arnold Shaw (Ilford South)

- Terence Walker (Kingswood)

- Bruce Grocott (Lichfield and Tamworth) - Parliamentary Private Secretary

- Margaret Beckett (Lincoln) - Parliamentary Under Secretary of State at the Department of Education and Science

- Edward Loyden (Liverpool Garston)

- Ivor Clemitson (Luton East)

- Brian Sedgemore (Luton West)

- John Desmond Cronin (Loughborough)

- John Tomlinson (Meriden) - Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State at Foreign Office

- Doug Hoyle (Nelson and Colne)

- Edward Bishop (Newark) - Minister for Agriculture, Fisheries and Food

- Maureen Colquhoun (Northampton North)

- Evan Luard (Oxford)

- Arthur Latham (Paddington)

- Michael Ward (Peterborough)

- Frank Judd (Portsmouth North) - Minister for Overseas Development

- Ronald Atkins (Preston North)

- Hugh Jenkins (Putney) - Minister for the Arts

- Robert Bean (Rochester and Chatham)

- Michael Noble (Rossendale)

- William Price (Rugby)

- Bryan Gould (Southampton Test)

- Raphael Tuck (Watford)

- Helene Hayman (Welwyn and Hatfield)

- Gerald Fowler (The Wrekin) - Minister for Education and Science

Liberal

Scottish National Party

- Douglas Henderson (East Aberdeenshire)

- Andrew Welsh (South Angus)

- Iain MacCormick (Argyll)

- Hamish Watt (Banffshire)

- Margaret Ewing (East Dunbartonshire)

- George Thompson (Galloway)

- Winnie Ewing (Moray and Nairn)

- Douglas Crawford (Perth & East Perthshire)

- George Reid (Clackmannan and East Stirlingshire)

Plaid Cymru

Scottish Labour Party

- Jim Sillars (South Ayrshire) - Former Labour MP

Ulster Vanguard

See also

References

- 1 2 Andy Beckett, When the Lights Went Out: Britain in the Seventies, London: Faber, 2009, p.460

- ↑ BBC 1979 Election coverage From Youtube

- ↑ Beckett, Andy (2010). When the Lights Went Out; Britain in the Seventies. Faber & Faber. p. 175. ISBN 978-0-571-22137-0.

- ↑ "UK | UK Politics | The Basics | past_elections | 1979: Thatcher wins Tory landslide". BBC News. 5 April 2005. Retrieved 4 May 2012.

- ↑ Anthony Seldon and Kevin Hickson New Labour, Old Labour: The Wilson and Callaghan Governments 1974-1979, London: Routledge, 2004, p.293

- ↑ "Political Science Resources: politics and government around the world". Psr.keele.ac.uk. Retrieved 2010-05-13.

- 1 2 Caryl, Christian (2014). Strange Rebels: 1979 and the Birth of the 21st Century. Basic Books. 3391-3428.

- ↑ Hugo Young, One of Us (Pan, 1990), p. 131.

- ↑ John Campbell, Margaret Thatcher: The Grocer's Daughter (Jonathan Cape, 2000), p. 432.

- ↑ "Speech to Conservative Rally in Cardiff | Margaret Thatcher Foundation". Margaretthatcher.org. Retrieved 2010-05-13.

- ↑ David Butler, Dennis Kavanagh, The British general election of 1979 (1999), p. 154

- ↑ Keesing's Record of World Events Volume 25, (June, 1979) p. 29633

- ↑ David Butler and Dennis Kavanagh, The British General Election of 1979 (Macmillan, 1980), p. 343

Further reading

- Butler, David E. et al. The British General Election of 1979 (1980) the standard scholarly study

- Campbell, John, and David Freeman. Margaret Thatcher, Volume 1: The Grocer's Daughter (2008)

- F. W. S. Craig British Electoral Facts: 1832-1987

- Jenkins, Peter. Mrs. Thatcher's Revolution: The Ending of the Socialist Era (1989)

- McAllister, Ian and Mughan, Anthony. "Attitudes, Issues, and Labour Party Decline in England, 1974-1979," Comparative Political Studies. (1985) 18#1 pp 37–57.

- Penniman, Howard R. Britain at the Polls, 1979: A Study of the General Election (1981) 345p.

- Särlvik, Bo; and Ivor Crewe. Decade of Dealignment: The Conservative Victory of 1979 & Electoral Trends in the 1970s (1983) 393p.

- United Kingdom election results - summary results 1885-1979

Manifestos

- Conservative manifesto, 1979 - 1979 Conservative manifesto.

- The Labour Way is the Better Way - 1979 Labour Party manifesto.

- The Real Fight is for Britain - 1979 Liberal Party manifesto.

.jpg)