Ultra-high-temperature processing

Ultra-high temperature processing (UHT), ultra-heat treatment, or ultra-pasteurization[1] is a food processing technology that sterilizes liquid food, chiefly milk, by heating it above 135 °C (275 °F) – the temperature required to kill spores in milk – for 1 to 2 seconds.[2] UHT is most commonly used in milk production, but the process is also used for fruit juices, cream, soy milk, yogurt, wine, soups, honey, and stews.[2] UHT milk was first developed in the 1960s and became generally available for consumption in the 1970s.[3]

The heat used during the UHT process can cause Maillard browning and change the taste and smell of dairy products.[4] An alternative process is HTST pasteurization (high temperature/short time), in which the milk is heated to 72 °C (162 °F) for at least 15 seconds.

UHT milk packaged in a sterile container, if not opened, has a typical unrefrigerated shelf life of six to nine months. In contrast, HTST pasteurized milk has a shelf life of about two weeks from processing, or about one week from being put on sale.[5]

History

The most commonly applied technique to provide a safe and shelf-stable milk is heat treatment. The first system involving indirect heating with continuous flow (125 °C for 6 min) was manufactured in 1893. In 1912, a continuous-flow, direct-heating method of mixing steam with milk at temperatures of 130 to 140 °C was patented. However, without commercially available aseptic packaging systems to pack and store the product, such technology was not very useful in itself, and further development was stalled until the 1950s. In 1953, APV pioneered a steam injection technology, involving direct injection of steam through a specially designed nozzle which raises the product temperature instantly, under brand name Uperiser; milk was packaged in sterile cans. In the 1960s APV launched the first commercial steam infusion system under the Palarisator brand name.[6][7]

In Sweden, Tetra Pak launched tetrahedral paperboard cartons in 1952. They made a commercial breakthrough in the 1960s, after technological advances, combining carton assembling and aseptic packaging technologies, followed by international expansion. In aseptic processing, the product and the package are sterilized separately and then combined and sealed in a sterile atmosphere, in contrast to canning, where product and package are first combined and then sterilized.[8]

Technology

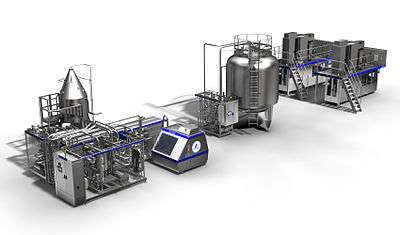

Ultra-high-temperature processing is performed in complex production plants, which perform several stages of food processing and packaging automatically and in succession:[9]

- Heating

- Flash cooling

- Homogenization

- Aseptic packaging

In the heating stage, the treated liquid is first pre-heated to a non-critical temperature (70–80°C for milk), and then quickly heated to the temperature required by the process. There are two types of heating technologies: direct, where the product is put in a direct contact with the hot steam, and indirect, where the product and the heating medium remain separated by the equipment's contact surfaces. The main goals of the design, both from product quality and from efficiency standpoints, are to maintain the high product temperature for the shortest period possible, and to ensure that the temperature is evenly distributed throughout.[9][10]

Direct heating systems

Direct systems have an advantage that the product is held at a high temperature for a shorter period of time, thereby reducing the thermal damage for the sensitive products such as milk. There are two groups of direct systems:[10]

- Injection-based, where the high-pressure steam is injected into the liquid. It allows fast heating and cooling, but is only suitable for some products. As the product comes in contact with the hot nozzle, there is a possibility of local overheating.

- Infusion-based, where the liquid is pumped through a nozzle into a chamber with high-pressure steam at a relatively low concentration, providing a large surface contact area. This method achieves near-instantaneous heating and cooling and even distribution of temperature, avoiding local overheating. It is suitable for liquids of both low and high viscosity.

Indirect heating systems

In indirect systems, the product is heated by a solid heat exchanger similar to those used for pasteurization. However, as higher temperatures are applied, it is necessary to employ higher pressures in order to prevent boiling.[9] There are three types of exchangers in use:[10]

- Plate exchangers,

- Tubular exchangers

- Scraped-surface exchangers.

For higher efficiency, pressurized water or steam is used as the medium for heating the exchangers themselves, accompanied with a regeneration unit which allows reuse of the medium and energy saving. [9]

Flash cooling

After heating, the hot product is passed to a holding tube and then to a vacuum chamber, where it suddenly loses the temperature and vaporizes. The process, referred to as flash cooling, reduces the risk of thermal damage, removes some or all of excess water obtained through the contact with steam, and removes some of volatile compounds which negatively affect the product quality. Cooling rate and the quantity of water removed is determined by the level of vacuum, which must be carefully calibrated.[9]

Homogenization

Homogenization is part of the process specific for milk. Homogenization is a mechanical treatment which results in decrease of size and increase of number and total surface area of fat globules in milk number. That, in turn, reduces milk's tendency to form cream at the surface and on contacts with container, enhances its stability, and makes it more palatable for consumers.[11]

Aseptic packaging

Aseptic packaging refers to technique in which previously sterilised milk is aseptically packaged in a sterile package and hermetically sealed to have prolonged shelf life even under ambient conditions.

Worldwide use

UHT milk has seen large success in much of Europe, where across the continent as a whole 7 out of 10 Europeans drink it regularly.[12] In fact, in a hot country such as Spain, UHT milk is preferred due to high costs of refrigerated transportation and "inefficient cool cabinets".[13] UHT is less popular in Northern Europe and Scandinavia, particularly in Denmark, Finland, Norway, Sweden, the United Kingdom and Ireland. It is also less popular in Greece, where fresh pasteurized milk is the most popular type of milk. This may be largely due to the differential rates of lactose intolerance within Europe; populations with high tolerance can drink milk in large amounts, making the lower palatability of UHT milk more noticeable.

| Country | percent |

|---|---|

| | 20.3 |

| | 96.7 |

| | 73[15] |

| | 71.4 |

| | 0.0 |

| | 2.4 |

| | 95.5 |

| | 88.1 |

| | 66.1 |

| | 0.9 |

| | 35.1 |

| | 10.9 |

| | 49.8 |

| | 20.2 |

| | 5.3 |

| | 48.6 |

| | 92.9 |

| | 35.5 |

| | 7.2 |

| | 95.7 |

| | 5.5 |

| | 62.8 |

| | 53.1 |

| | 8.4 |

In June 1993, Parmalat introduced its UHT milk to the United States.[16] In the American market, consumers are uneasy about consuming milk that is not delivered under refrigeration, and reluctant to buy it. To combat this, Parmalat is selling its UHT milk in old-fashioned containers, unnecessarily sold from the refrigerator aisle.[5] UHT milk is also used for many dairy products.

UHT milk is sold on American military bases in Puerto Rico[17] and Korea due to limited availability of milk supplies and refrigeration.

UHT milk gained popularity in Puerto Rico as an alternative to pasteurized milk due to environmental factors. For example, power outages after a hurricane can last up to 2 weeks, during which time pasteurized milk would spoil from lack of refrigeration.

In 2008 the UK government proposed a 90% UHT milk production target by 2020[18] which they believed would significantly cut the need for refrigeration, and thus benefit the environment by reducing green house emissions.[19] However the milk industry opposed this, and the proposition was abandoned.

Nutritive effects

- Calories

- UHT milk contains the same number of calories as pasteurized milk.

- Calcium

- UHT and pasteurized milk contain the same amount of calcium.

- Protein

- UHT milk's protein structure is different from that of pasteurized milk, which prevents it from separating in cheese making.[20]

- Folate

- Vitamin B12, vitamin C and thiamin

- Some nutritional loss can occur in UHT milk.[22]

See also

References

- ↑ "CFR - Code of Federal Regulations Title 21". FDA. April 1, 2016.

- 1 2 "UHT Processing". University of Guelph, Department of Dairy Science and Technology. Retrieved 2008-01-07.

- ↑ Elliott, Valerie (2007-10-15). "Taste for a cool pinta is a British Tradition". London: The Times. Retrieved 2008-04-03.

- ↑ Clare, D.A.; W.S. Bang; G. Cartwright; M.A. Drake; P. Coronel; J. Simunovic (1 December 2005). "Comparison of Sensory, Microbiological, and Biochemical Parameters of Microwave Versus Indirect UHT Fluid Skim Milk During Storage". Journal of Dairy Science. 88 (12): 4172–4182. PMID 16291608. doi:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(05)73103-9.

- 1 2 "Why does organic milk last so much longer than regular milk?". scientificamerican.com.

- ↑ "Long Life Dairy, Food and Beverage Products" (PDF). SPX Flow Technology. p. 16.

- ↑ Chavan, R. S.; Chavan, S. R.; Khedkar, C. D.; Jana, A. H. (2011). "UHT Milk Processing and Effect of Plasmin Activity on Shelf Life: A Review". Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety (10:): 251–268. doi:10.1111/j.1541-4337.2011.00157.x.

- ↑ "Tetra Pak vs Plastic Water Bottles?". The Guardian. Retrieved 2016-05-11.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Alan H. Varnam (6 December 2012). Milk and Milk Products: Technology, chemistry and microbiology. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 58–62. ISBN 978-1-4615-1813-6.

- 1 2 3 Duizer, Lisa. "UHT Methods". The Dairy Science and Technology eBook. University of Guelph, Food Science.

- ↑ Duizer, Lisa. "Homogenization of Milk and Milk Products". The Dairy Science and Technology eBook. University of Guelph, Food Science.

- ↑ Solomon. Zaichkowsky, Polegato.Consumer Behavior: Pearson, Toronto. 2005. pg 39

- ↑ "Without prejudice.". Dairy Industries International. Retrieved 2008-04-03.

- ↑ Elliott, Valerie (2007-10-15). "The UHT route to long-life planet". London: Times Online. Retrieved 2008-03-01.

- ↑ "Udio trajnog mlijeka veći od 70%". Ja Trgovac. Retrieved 2010-03-05.

- ↑ Janofsky, Michael (1993-06-26). "Seeking to Change U.S. Tastes; Italian Company Sings The Praises of UHT Milk". The New York TImes. Retrieved 2008-04-03.

- ↑ "Dairyman wants to send milk to Middle East". Deseret News. Retrieved 2008-04-03.

- ↑ "Dairy Road Map outlines target for greenhouse gas cut". Farmers Guardian. Retrieved 2008-04-03.

- ↑ Elliott, Valerie (2007-10-15). "The UHT route to long-life planet". London: Times Online. Retrieved 2008-04-03.

- ↑ "How To Make Paneer Cheese in 30 Minutes". The Kitchn. Retrieved 2014-02-19.

- ↑ "Taste for a cool pinta is a British tradition". The Times. Retrieved 2008-04-03.

- ↑ Greg Morago (27 December 2003). "UHT: Milking it for all it's worth". Hartford Courant. Retrieved 2008-04-03.

External links

- An article focusing on the negative aspects of UHT milk from the Weston A. Price Foundation

- Milk in a Box. From: Interesting Thing of the Day