U-Tapao Royal Thai Navy Airfield

| U-Tapao Royal Thai Navy Base | |

|---|---|

| Part of Royal Thai Navy (RTN) | |

| Coordinates | 12°40′47″N 101°00′18″E / 12.67972°N 101.00500°E |

| Type | Naval Air Base |

| Site information | |

| Condition | Military Naval Air Base |

| Site history | |

| Battles/wars |

Vietnam War |

| Airfield information | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Summary | |||||||||||

| Elevation AMSL | 42 ft / 13 m | ||||||||||

| Coordinates | 12°40′47″N 101°00′18″E / 12.67972°N 101.00500°ECoordinates: 12°40′47″N 101°00′18″E / 12.67972°N 101.00500°E | ||||||||||

| Map | |||||||||||

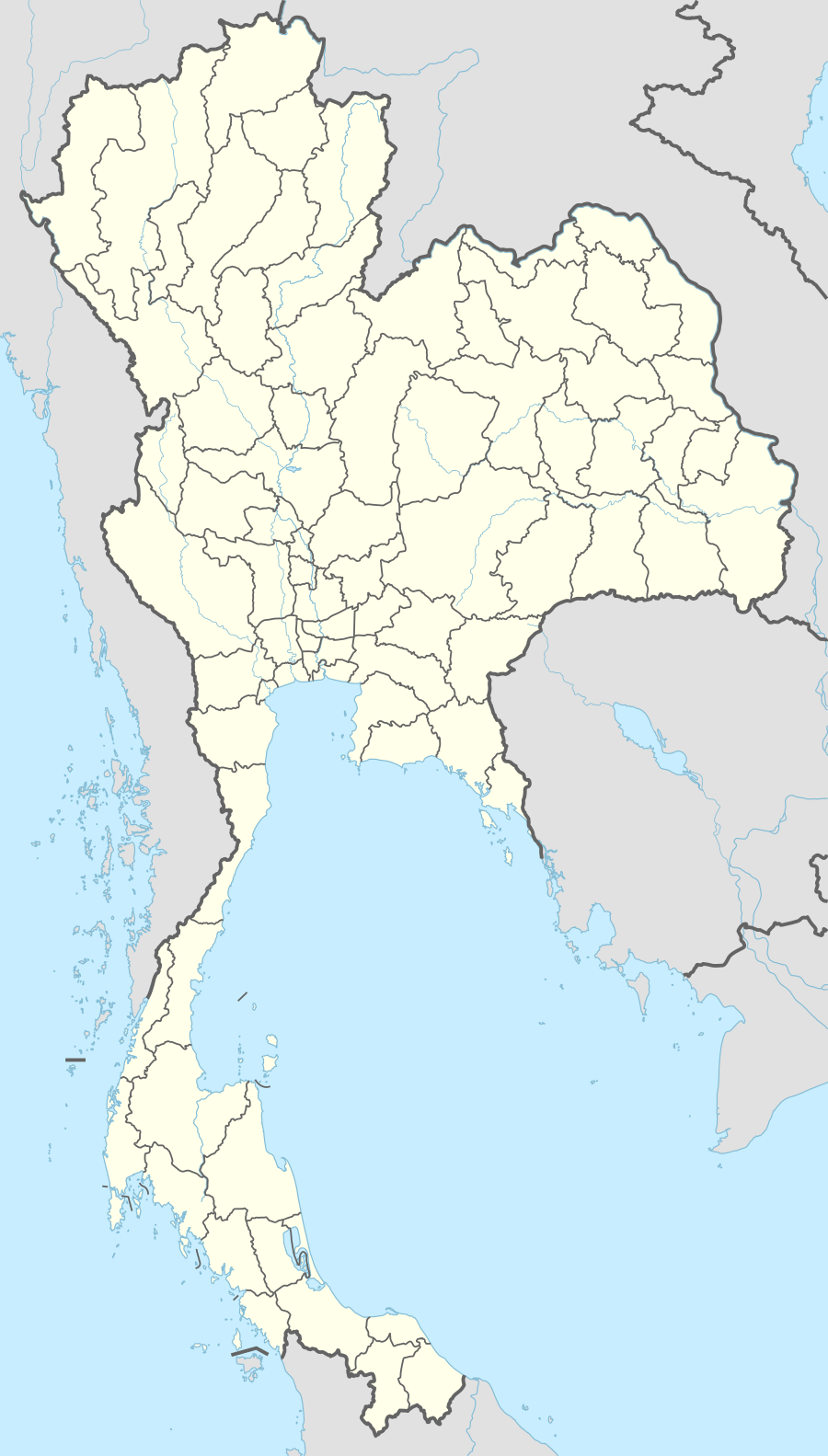

VTBU Location of U-tapao Royal Thai Navy Airfield | |||||||||||

| Runways | |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

U-Tapao Royal Thai Navy Airfield is a military airfield of the Royal Thai Navy approximately 140 kilometres (87 mi) southeast of Bangkok in the Ban Chang District of Rayong Province near Sattahip on the Gulf of Siam. It is serves as the home of the Royal Thai Navy First Air Wing.

Name

U-Tapao (Thai: อู่ตะเภา) is a compound of อู่ cradle and ตะเภา trade winds, and derives from the site having once been a shipyard for construction of ruea-tapao (เรือตะเภา), a type of argosy resembling a Qing Dynasty junk.

Units

U-Tapao is the main flying base for the Royal Thai Navy. Squadrons based there include:

- No 101 Squadron flying Dornier DO-228-212 (seven aircraft)

- No 102 Squadron flying Lockheed P-3T/UP-3T (three aircraft) and Fokker F-27-200ME aircraft (a total of three, at least one of which is in store)

- No 103 Squadron flying Cessna 337 H-SP (10 aircraft, some may be stored)

- No 201 Squadron flying Canadair CL-215 (one aircraft), GAF Nomad N-24A (three aircraft, a fourth aircraft is in store) and Fokker F-27-400M (two aircraft)

- No 202 Squadron flying Bell 212 helicopters (approximately six)

- No 203 Squadron flying Bell 214SP helicopters (recently grounded after a fatal crash killing nine crew members on 23 March 2007), Sikorsky S-76B (six helicopters) and Super Lynx Mk.110 (two helicopters)

- No 302 Squadron flying Sikorsky S-70B Seahawk anti-submarine helicopters (six in service)

Two squadrons are dormant

- No 104 Squadron which flew 14 A-7E and 4 TA-7C Corsair strike aircraft

- No 301 Squadron which flew AV-8S and TAV-8S (two aircraft)

Current military use

For several years, beginning in 1981, U-Tapao has hosted parts of Cobra Gold, the largest US military peacetime exercise in the Pacific, jointly involving US, Singaporean, and Thai armed forces, and designed to build ties between the nations and promote interoperability between their military components.

Thailand is an important element in The Pentagon's strategy of "forward positioning". Despite Thailand's neutrality on the 2003 invasion of Iraq, the Thai government allowed U-Tapao to be used by American warplanes flying into combat in Iraq, as it had earlier done during the war in Afghanistan. In addition, U-Tapao may be where Al Qaeda operative Abu Zubaydah was interrogated, according to some retired American intelligence officials.[3]

A multinational force headquarters was established at U-Tapao to coordinate humanitarian aid for the Sumatran tsunami of 26 December 2004.

On 7 May 2008, in the aftermath of Cyclone Nargis, Thai C-130 transports were permitted to land at Yangon International Airport in Burma, carrying drinking water and construction material.[4]

From 12–20 May, USAID and the U.S. Department of Defense (DOD) coordinated the delivery of nearly US$1.2 million of relief commodities to Yangon on 36 DOD C-130 flights, with supplies sufficient to provide assistance to more than 113,000 beneficiaries. The DOD efforts were under the direction of Joint Task Force Caring Response.[5]

As of 26 June 2008, United States assistance directed by the USAID DART (Disaster Assistance Response Team) stationed in Thailand, had totaled US$41,169,769.[6] Units involved were the 36th Airlift Squadron (36 AS) of the 374th Airlift Wing (374 AW) from Yokota Air Base, Japan, flying C-130H Hercules; and Marine Aerial Refueler Transport Squadron 152 (VMGR-152) from Marine Corps Air Station Futenma, Okinawa, Japan, flying the Lockheed Martin KC-130R and the newer KC-130J.

In 2012, a proposal for the United States National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) to use U-Tapao to support weather research was rejected by the Thai government.[7]

In 2015, a Politico article reported that the United States Government rented space at U Tapao from a private contractor for use as a "major logistics hub for the Iraq and Afghanistan wars." Because the lease was technically with a private contractor, this allowed "U.S. and Thai officials to insist there's no U.S. 'base' and no inter-governmental basing agreement."[8]

US use of U-Tapao during the Vietnam War

Prior to 1965, the base at U-Tapao was a small Royal Thai Navy airfield. At Don Muang Air Base near Bangkok, the USAF had stationed KC-135 air-refuelling tanker aircraft from the Strategic Air Command (SAC) to refuel combat aircraft over the skies of Indochina. Although Thailand was an active participant in the Vietnam War, with a token ground force deployed to the Republic of Vietnam (South Vietnam) as well as involved in the largely-secret civil war in Laos, the presence and the visibility of US Air Force tanker aircraft near its capital city was causing a fair degree of political embarrassment for Thailand's military government.

In June 1965, the B-52F was first used in the Vietnam War. B-52F aircraft from the 7th and 320th Bomb Wings were sent to bomb suspected Viet Cong enclaves in South Vietnam. The B-52Fs were stationed at Andersen AFB on Guam, the operation being supported by KC-135As stationed at Kadena AB on Okinawa. By November 1965, B-52s supported the 1st Air Cavalry Division in mopping up operations near Pleiku.

The Seventh Air Force (PACAF) wanted additional B-52s missions flown in the war zone. B-52 missions from Andersen and Kadena AB, Okinawa, however, required long mission times and aerial refuelling en route. Having the aircraft based in South Vietnam made them vulnerable to attack. It was decided that, as the base at U-Tapao was being established as a KC-135 tanker base, to move them all out of Don Muang and to also base B-52s at U-Tapao where they could fly without refuelling over both North and South Vietnam.

The construction of U-Tapao Royal Thai Navy Airfield began in October 1965. The runway was built in eight months[9] and the base was completed slightly more than two years later.[10][11][12] The 11,500-foot (3,505 m) runway was opened on 6 July 1966 and the first aircraft to land was a Royal Thai Air Force HH-16 helicopter, then a USAF C-130 Hercules cargo aircraft.

With the completion of U-Tapao, most US forces were transferred from Don Muang, and U-Tapao RTNAF became a front-line facility of the United States Air Force in Thailand from 1966 to 1975.

The USAF forces at U-Tapao were under the command of the United States Pacific Air Forces (PACAF), with the Strategic Air Command (SAC) units being a tenant unit. The APO for U-Tapao was APO San Francisco, 96330

4258th Strategic Wing

The 4258th Strategic Wing (SAC) was activated in June 1966 at U-Tapao under the 3rd Air Division, Andersen AFB, Guam. The wing was charged with the responsibility of supporting refueling requirements of USAF fighter aircraft in Southeast Asia, plus conducting bombing missions on a daily basis.

Steadily progressing and adding to the mission, U-Tapao welcomed its first complement of KC-135 tankers in August 1966. By September, the base was supporting 15 tankers. From 1966 to 1970, 4258th wing tankers flew over 50,000 sorties from U-Tapao.

On 10 April 1967, three B-52 bombers landed at U-Tapao following a bombing mission over Vietnam. The next day, B-52 operations were initiated at U-Tapao. Under the operational nickname "Arc Light", wing bombers flew over 35,000 strikes against the enemy from 1967 to 1970.

B-52 missions from U-Tapao

Although the B-52F carried out the first B-52 missions in Southeast Asia, less than six months later, the Air Force decided to convert most of its B-52Ds to conventional warfare capability for service in Southeast Asia. Modifications were needed to give the B-52D the ability to carry a significantly larger load of conventional bombs, which led to the Big Belly project that was begun in December 1965. The project increased the internal bomb capacity from 27 weapons to a maximum of 84 500-lb Mk 82 or 42 750 lb M117 conventional bombs. This was done by rearrangement of internal equipment, and did not change the outside of the aircraft. In addition, a further 24 bombs of either type could be carried on modified under-wing bomb racks (originally designed to carry AGM-28 Hound Dog cruise missiles and fitted with I-beam rack adapters and a pair of multiple ejection racks), bringing the maximum payload to 60,000 pounds (27,000 kg) of bombs, about 22,000 pounds (10,000 kg) more than the capacity of the B-52F.

Between 1966 and 1975, SAC B-52 squadrons (mostly B-52D, but some B-52G) were rotated to combat duty in Southeast Asia. SAC crews who ordinarily would have been assigned to the B-52G or H models were sent through an intensive two-week course, mostly on the B-52D, making them eligible for duty in Southeast Asia. Camouflage paint in tan and two shades of green, still with white undersides, was applied to B-52s when other USAF aircraft were adopting camouflage. B-52Ds assigned to combat duty in Vietnam were painted in a modified camouflage scheme with the undersides, lower fuselage, and both sides of the vertical fin being painted in a glossy black. The USAF serial number was painted in red on the fin.

In early-October 1968, a KC-135A tanker (55-3138)[13] lost power in the outside right engine (#4) on takeoff at U-Tapao and crashed, killing all four crew members.[14][15]

Known SAC units at U-Tapao

U-Tapao was initially more of a forward field than it was a main operating base, with responsibility for scheduling missions still remaining at Andersen AFB. Small numbers of aircraft were drawn from each SAC B-52D unit to support the effort in Thailand. Known squadrons which deployed B-52 and KC-135 aircraft and crews to U-Tapao were:

- 9th Bombardment Squadron, 7th Bombardment Wing (Heavy), Carswell AFB, Texas

- 2nd Bombardment Squadron, 22nd Bombardment Wing (Heavy), March AFB, California

- 77th Bombardment Squadron, 28th Bombardment Wing (Heavy), Ellsworth AFB, South Dakota

- 6th Bombardment Squadron, 70th Bombardment Wing (Heavy), Clinton-Sherman AFB, Oklahoma

- 322nd Bombardment Squadron, 91st Bombardment Wing (Heavy), Glasgow AFB, Montana

- 325th Bombardment Squadron, 92nd Bombardment Wing (Heavy), Fairchild AFB, Washington

- 328th & 329th Bombardment Squadrons, 93rd Bombardment Wing (Heavy), Castle AFB, California

- 337th Bombardment Squadron, 96th Strategic Aerospace Wing, Dyess AFB, Texas

- 346th & 348th Bombardment Squadrons, 99th Bombardment Wing, Westover AFB, Massachusetts

- 367th Bombardment Squadron, 306th Bombardment Wing (Heavy), McCoy AFB, Florida

- 486th Bombardment Squadron 1966–1970, 22d Bombardment Wing (Heavy), March AFB, California

- 528th Bombardment Squadron 1969, 380th Strategic Aerospace Wing (Heavy), Plattsburgh AFB, New York

- 716th Bombardment Squadron, 449th Bombardment Wing (Heavy), Kincheloe AFB, Michigan

- 736th Bombardment Squadron, 454th Bombardment Wing (Heavy), Columbus AFB, Mississippi

- 764th Bombardment Squadron, 461st Bombardment Wing, Amarillo AFB, Texas

- 393rd Bombardment Squadron, 509th Bombardment Wing (Heavy), Pease AFB, New Hampshire

- 912th Air Refueling Squadron, 19th Bombardment Wing, Robins AFB, Georgia

- 920th Air Refueling Squadron, 379th Bombardment Wing, Wurtsmith AFB, Michigan

- 69th Bombardment Squadron, 42nd Bombardment Wing, Loring AFB, Maine

These units deployed usually on 90 days tours.

Sapper attack

On 24 December in 1971, a small group of enemy insurgents, most likely from the communist People's Liberation Army of Thailand (the PLAT, which was the Communist Party of Thailand's armed wing), attempted to destroy USAF B-52 bomber aircraft with sappers and military engineers using satchel charges and dynamite-filled packages (in a similar fashion to that of a sabotage mission). While it remains unclear and uncertain regarding the size of the attacking insurgent group, a rough estimate of the number of attackers vary from three to more than 10, with off-base fire support (from mortars). Gunfire and firefights between the insurgents and the defending US Air Force base security forces were exchanged and there were a number of explosions that occurred simultaneously. This still remains as the only officially-reported enemy attack against U-Tapao air base.

Khe Sanh

One of the most important actions of the B-52 in the Vietnam War was during the siege of Khe Sanh in early 1968. The North Vietnamese surrounded an isolated US Marine outpost there and began conducting a methodical siege, building trenches that crept closer to the outpost while the two sides traded fire.

Concentrated bombardments by B-52s with unbroken waves of six aircraft, attacking every three hours, dropped bombs as close as 900 feet (270 m) from the perimeter of the outpost, cratered the North Vietnamese entrenchments and inflicted heavy casualties, forcing them to give up the siege. 2,548 B-52 sorties were flown under the appropriately-named OPERATION NIAGARA in support of the defense of Khe Sanh, dropping a total of 54,129 tonnes (59,542 tons) of bombs.

Raids were not only flown out of Andersen AFB and U-Tapao, but from Kadena Air Base on Okinawa, where B-52Ds had been sent to counter aggressive North Korean moves. The fact that Kadena was performing raids on Southeast Asia was kept secret to avoid inflaming Japanese public opinion.

While the bombers were formally restricted from dropping their bombs any closer than a kilometer from the Khe Sanh base perimeter, the Marines lied to the aircrews and sometimes put them at 500 metres (1,600 ft) or even closer. When the enemy finally withdrew, US forces scouting the abandoned North Vietnamese positions found a moonscape of craters with no trees standing, littered with hundreds of enemy dead.

Raids in Cambodia

Beginning in March 1969, B-52s were raiding not only South Vietnam and Laos, but Cambodia as well. The Nixon Administration had approved this expansion of the war not long after entering office in the spring of 1969. Cambodian bombing raids were initially kept secret, and both SAC and Defense Department records were falsified to report that the targets were in South Vietnam.

The Cambodian raids were carried out at night under the direction of ground units using the MSQ-77 radar, which guided the bombers to their release points and indicated the precise moment of bomb release. This made deception easier, as even crew members aboard the bombers did not have to know what country they were bombing. However, the specific flight coordinates (longitude and latitude) of the points of bomb release were noted in the navigator's logs at the end of each mission, and a simple check of the map could tell the crews which country they were bombing.

The Cambodian effort would eventually turn out to be something of a fiasco. It is unclear how much damage was done to North Vietnamese Army in their enclaves there, but it is clear that the raids did much to destabilize the Cambodian government, eventually leading to the downfall of the Norodom Sihanouk government and the rise of the savage Khmer Rouge regime.

Raids in North Vietnam

U-Tapao based B-52s carried out Operation Arc Light attacks on North Vietnam, although at first only the very southernmost part near the Demilitarized Zone was hit. The B-52s generally avoided North Vietnamese airspace at this stage in the war lest one of them fall victim to a Surface-to-air missile (SAM), which would have been a propaganda coup for North Vietnam (they could thus claim to be a victim of US aggression and gain a degree of international support).

307th Strategic Wing

On 21 January 1970, the 4258th SW was redesignated as the 307th Strategic Wing. The 307th was the only regular Air Force SAC Wing stationed in Southeast Asia. The 307th was under the command and control of Eighth Air Force, based at Andersen AFB, Guam.

Four provisional squadrons were organized under the 307th:

- Bombardment Squadron (Provisional), 364, 1973–1975

- Bombardment Squadron (Provisional), 365, 1973–1974. Disbanded 7/17/74

- Bombardment Squadron (Provisional),486, 1970–1971

- Air Refueling Squadron (Provisional), 901, 1974–1975

In addition, two four-digit bomb squadrons (4180th, 4181st) were assigned, but were not operational.

Operation Linebacker

The Vietnamization of the Vietnam war was put to the test in the spring of 1972, when the North Vietnamese launched a full-scale offensive across the Vietnamese Demilitarized Zone (DMZ), supported by tanks and heavy artillery. By this time, the US was no longer in the forefront of the ground war, with South Vietnamese units taking the lead. However, the US was still providing air power, and US combat planes flew vast numbers of strikes. Although there had been no campaign of strikes into North Vietnam since the end of Rolling Thunder, the Nixon Administration ordered a new air offensive, initially code named Freedom Train, later becoming Linebacker, with relatively few restrictions on targets that could be hit.

The B-52s conducted a limited number of strikes against North Vietnam as part of the spring 1972 invasion, though most of their sorties were on Arc Light missions elsewhere. The North Vietnamese offensive was crushed, but the strikes on North Vietnam continued, only winding down in October, ahead of the United States presidential election, 1972, which resulted in Richard Nixon being re-elected and the attacks quickly ramped up again in November.

In late 1972, B-52s were confronted with surface-to-air missile (SAM) defenses. On 22 November 1972, a B-52D was damaged by an SA-2 SAM in a raid on Vinh, an important rail center in the southern part of North Vietnam. The bomber's pilot managed to get the burning aircraft back to Thailand before the crew bailed out, leaving the aircraft to crash. All the crew were recovered safely.

Operation Linebacker II

Since 1967, the US had been negotiating with North Vietnam to allow a peaceful withdrawal and repatriate prisoners of war (POWs). The negotiations had been frustrating and quarrelsome. In late-1972 the Nixon Administration ran out of patience and ordered an all-out air offensive against North Vietnam.

The bombing raids began on 18 December 1972. The new campaign, codenamed Linebacker II, involved heavy attacks by almost every strike aircraft the US had in theater, with the B-52 playing a prominent role. The initial plan scheduled attacks for three days. Along with heavy strikes by Air Force and Navy tactical aircraft, 129 B-52s in three waves (approximately four hours apart) from the 307th Strategic Wing at U-Tapao RTNAF and B-52Ds and B−52Gs of both wings based at Andersen AFB, the 43d Strategic Wing and the 72 Strategic Wing (Provisional). These went into battle on the night of 18 December, with the crews under strict orders to fly straight and level on approach and not release bombs unless they were sure they were on target.

The B-52s were assisted by F-4 Phantoms laying down corridors of chaff and providing Barrier Combat air patrol (BARCAP) against North Vietnamese MiG-17s. Lockheed EC-121 College Eye radar aircraft tracked the comings and goings of enemy fighters. F-105 Thunderchiefs performed "Wild Weasel" attacks on surface-to-air missile (SAM) sites. EB-66 Destroyer jamming aircraft blinded enemy radar and communications.

Three B-52s were lost on 18 December. Ninety-three flew raids on 19 December, with no losses, but the strike plan was basically the same as it had been the day before. Though radar jamming denied SAM crews targeting data, North Vietnamese noticed a pattern. Ninety-nine B-52s flew strikes on 20 December, and SAM sites fired their missiles in a shotgun pattern. Six aircraft were destroyed.

The Andersen AFB-based B-52Gs were taking a disproportionate share of the losses. The "wet wing" of the B-52G made it more vulnerable to battle damage, as did the fact that not all of the B-52Gs had the same level of countermeasures fitted as the B-52D. This was made all the more ironic because the B-52G, with no capability of carrying bombs on its external pylons, could only carry about a quarter the conventional bomb load of the B-52D. The B-52G could carry one rack with 27 MK-82 500 pound bombs, where the B-52D could carry three racks for a total of 84 500-lb Mk 82 or 42 750 lb M117 conventional bombs internal and 24 external bombs made for a total of 108 bombs. All Andersen Linebacker II missions required at least one (and some missions required two) aerial refuelings, supported by the 376th Strategic Wing based at Kadena AB.

The B-52Gs were ordered to stand down for two days while fixes were hurriedly implemented. Thirty B-52Ds out of U-Tapao flew strikes on 21 December with two more bombers lost. The next night, 22 December, 30 B-52Ds came back again, but this time their attacks were performed from unpredictable directions, and there were no losses. Strikes were made on SAM sites to help wear down the defenses for later.

The same approach, 30 bombers using unpredictable tactics, was repeated on the 23 and 24 December, once again with no losses.

On 26 December, a total of 120 B-52s performed raids, with 113 reaching their targets nearly simultaneously, all dropping their bombs within a space of 15 minutes, overwhelming the defenses. Two B-52s were lost, but the North Vietnamese were beginning to run out of SAMs and their air defenses were wobbly. Sixty B-52s came back on 27 December, with two lost, but this was the last gasp of the defenders. Sixty bombers hit again on the 28 and 29 December with no losses. The North Vietnamese agreed to negotiate on 29 December, and the B-52s halted strikes against North Vietnam.

In 11 days of concentrated bombing, B-52s had completed 729 sorties and dropped 13,640 tonnes (15,000 tons) of bombs. The North Vietnamese claimed that almost 1,400 civilians were killed.

The campaign was expensive, and not merely in financial terms. Sixteen B-52s were lost and nine others suffered heavy damaged, with 33 aircrew killed or missing in action. While the air force justifiably regarded the B-52 losses as severe, North Vietnamese SAMs had been ineffective, with a hit rate of eight percent (334 SA-2 missile were fired). North Vietnamese MiG interceptors proved ineffective at taking on the B-52s. According to US statistics, the MiGs scored no kills and two of them were claimed shot down by the "quad-fifties" in B-52 tail turrets. However, North Vietnamese records insist that two of the B-52s shot down were MiG kills.

Although the unrestricted bombing campaign was referred to by critics as "an attempt to pillage and burn the enemy to the conference table", LINEBACKER II, sometimes called the "Eleven-Day War", was believed by many as devastatingly successful in achieving its goals. Henry Kissinger contrasted the extremely uncooperative attitude of North Vietnamese negotiators before the raids with the great willingness to talk after them, and concluded, "These facts have to be analyzed by each person for himself." The North Vietnamese account was that the operation did not achieve its goals. Vo Nguyen Giap's claimed that the US had boycotted the negotiations, and Operation Linebacker II was an attempt to force the Vietnamese to accept a "peace solution". He attributed the small number of civilian deaths, not to the bombing's accuracy, but the fact that Hanoi was almost emptied. In the end, the Paris Peace Accord was signed with terms favorable to North Vietname, and Nixon had to force Thieu, President of South Vietnam into signing it the accord, with the threat of a coup against him.

A cease-fire was signed on 23 January 1973, with US POWs being flown out of Hanoi beginning on 18 March. However, the B-52's war was not quite over, with Arc Light strikes on Laos continuing into April and on Cambodia into August. The 307th SW ended all combat operations on 14 August 1973.

1973 – 1975 premiership of Judge Sanya

A succession of staunchly pro-American and anti-Communist military dictatorships had ensured massive US economic and financial aid, and oft-repeated allegations of high-level corruption, frequently countered by suppression of public opinion. The 1973 uprising was largely due to actions by the student body of Thammasat University and directed against the "Three Tyrants": Field Marchall Thanom Kittikachorn, his son, and his son's father-in-law; the US military presence was not an issue.

On 14 October 1973, the "Three Tyrants" mistook the popular uprising — the first of its kind — as a coup d'état and fled the country, leaving it leaderless. As it had in fact not been a Thai military coup d'état, no military faction was positioned to assume control. Thus, on 14 October, former Supreme Court Judge Sanya Dharmasakti, then chancellor and dean of the faculty of law at Thammasat, was appointed prime minister by royal decree. (This established a precedent subsequently exercised only three times, for appointment of Prime Ministers of Thailand.) On 22 May 1974, Judge Sanya tendered his resignation. On 27 May, a House of Representatives resolution called on him to serve a second consecutive term, for a combined total of one year and 124 days.

The US military presence became an issue following collapse of the Khmer Republic of Marshall Lon Nol, the subsequent fall of Phnom Penh; and the 1975 South Vietnamese collapse, when many aircraft provided by the US, fled to U-Tapao.

The US had no interest in aircraft considered obsolete, but did undertake to recover a single Vietnamese F-5 Tiger II. The attempt to lift the F-5 off by helicopter failed when the harness broke. When Judge Sanya learned of it, he ordered further recovery efforts to cease until ownership of the aircraft could be determined in accordance with international law. Several C-7 Caribou were repainted with US markings, but were not then evacuated.

Judge Sanya's tenure also extended to the May 1975 Mayagüez incident. Judge Sanya, again in consideration of international law, denied use of U-Tapao as a staging area, but was ignored.

1975 South Vietnamese collapse

In the two years following the 1973 Paris Peace Accords and the War Powers Act, the North Vietnamese army underwent a massive rebuilding to recoup the losses suffered during their failed 1972 Easter Offensive. By the spring of 1975, the North Vietnamese Army had grown to be the fifth largest in the world, and in late-December 1974 began their drive towards Saigon. By the end of March 1975, North Vietnamese troops had captured several key cities, either because the ARVN forces were unequipped and undermanned, or because the outnumbered troops had fled at the approach of the enemy.

By the second week of April, the situation had deteriorated to the point that most of South Vietnam was under the control of the North Vietnamese Army. A congressional delegation had visited South Vietnam but was unable to convince President Ford to provide more aid. President Ford stated in a speech on 23 April that for the United States the Vietnam War "... was finished".

An estimated 8,000 U.S. and third-country nationals needed to be evacuated from Saigon and the shrinking government-controlled region of South Vietnam, along with thousands of Vietnamese who had worked for the United States during the war who would be in dire straits under the communists. The evacuation of Saigon was originally code-named "Talon Vice" and called for the evacuation of personnel via commercial aircraft from Tan Son Nhut Airport and other locations. The plan called for the ARVN to provide crowd control and to secure the evacuation areas. However, as the situation deteriorated rapidly in South Vietnam, the plan was changed to use rooftops as helicopter landing pads for evacuating personnel.

The evacuation plans were completed by 18 April and the name was changed to Operation Frequent Wind. U-Tapao Airfield was used as a jumping-off point by the USAF with eight CH-53 and two HH-53 "Sea Stallion" helicopters. Additional helicopters were standing by on board the USS Midway, and at the Nakhon Phanom and Ubon air bases. Korat placed a force of F-4s, A-7s, and AC-130s on alert. Udon discontinued its training flights and put its F-4 fighters on alert for combat missions over South Vietnam to support the evacuation.

On 25 April South Vietnamese President Thieu fled the country, and the final collapse of the South Vietnamese government was imminent. Aircraft started to arrive at U-Tapao in South Vietnamese markings. They arrived that day and the next several days. C-119s, C-130s, C-47s were filled to capacity with men, women and children. After their arrival, the Vietnamese were sequestered in tents near the runway. The adjacent parking ramps and grassy areas were being filled to capacity with South Vietnamese helicopters and aircraft, including many F-5E/F aircraft which had just been delivered to South Vietnam a few months earlier.

By 29 April the North Vietnamese had brought anti-aircraft artillery (AAA) and mobile surface-to-air missiles (SAM) to the Saigon area. Mortar and artillery rounds were impacting Tan Son Nhut Air Base, severely disrupting the evacuation activities. Marine guards at the US Embassy, Saigon shut off the electricity to the elevators and exploded tear gas canisters as they went to the roof to join the evacuees. The last helicopter left the embassy at 07:53 on 29 April. Douglas VC-47A 084 of Air America crashed on landing. The aircraft was on a flight from Tan Son Nhut International Airport.[16]

On 30 April the South Vietnamese government surrendered. The handful of South Vietnamese Air Force planes that had been performing last-ditch air strikes completed their missions and flew to U-Tapao. The last air rescue helicopters returned to Nakhon Phanom on 2 May. The war between North and South Vietnam was over.

Mayagüez incident

On 12 May 1975, less than two weeks after the fall of Saigon, a unit of the Cambodian Khmer Rouge navy seized the American-flagged container ship SS Mayaguez, taking the crew hostage. On 13 May, Seventh Air Force commander Lieutenant General John J. Burns and his staff developed a contingency plan for volunteers of the Nakhon Phanom Royal Thai Air Force Base 56th Security Police (SP) Squadron to be dropped onto the containers on the decks of the Mayaguez. The next morning, 75 SPs from the 56th boarded helicopters of 21st Special Operations Squadron to proceed to U-Tapao for staging. A CH-53 (AF Serial No 68-10933) crashed,[17] killing 18 SPs and the five-man flight crew. The hasty attempt to effect recovery of the vessel and her crew using only Air Force resources was abandoned; U-Tapao then served as a staging point for U.S. Marines[18] to deploy aboard the remaining CH-53s of the 21st SOS and HH-53s of the 40th Aerospace Rescue and Recovery Squadron, and assault Koh Tang Island. 15 May at sunrise, they hit the beach in the Air Force's first-ever helicopter assault operation.

Everything that could go wrong did. The Marines and helicopter crews never received good intelligence available about the island's defenders. They went in expecting 18 to 40 lightly armed militiamen but instead found a reinforced battalion of elite Khmer Rouge naval infantry. The Cambodians shot down three of the first four CH-53 helicopters to approach the island, one of them carrying the Marine forward air controller (FAC) team. The fourth was badly damaged and forced to abort. For hours, air force A-7s sent from Korat RTAFB to provide fire support failed to find the Marines, let alone support them. The Marines hung on while the remaining helicopters of the assault wave fed in reinforcements; the enemy badly shot up most of the remaining seven helicopters and only three landed in commission at U-Tapao. A boarding party, transferred to the USS Harold E. Holt (FF-1074) by helicopter, seized the Mayaguez, only to find the ship deserted. The Cambodians had taken its crew to the mainland two days earlier.

When the extraction began, only five helicopters were available, and one was quickly damaged and put out of commission. Maintenance provided one more as the rescue proceeded, providing a razor-thin margin of success.

USAF withdrawal

With the fall of both Cambodia and South Vietnam in the spring of 1975,[19] the political climate between Washington and the government of PM Sanya had become very sour, and the USAF was wanted out of Thailand by the end of the year. The USAF implemented Palace Lightning, the plan to withdraw its aircraft and personnel from Thailand. The SAC units left in December 1975;[20] however, the base remained under American control until it formally handed to the Thai government on 13 June 1976.[21]

USAF major units at U-Tapao

- 4258th Strategic Wing (1966–1970)

- 307th Strategic Wing (1970–1975)

- Young Tiger Tanker Force (1966–1975)

- Strategic Wing (Provisional), 310 (1972)

- Consolidated Aircraft Maintenance Wing (Provisiona), 340 (1972)

- 99th Strategic Reconnaissance Squadron (1972–1976)

- Air Division (Provisional), 310th (1972)

- 11th USAF Hospital

- 635th Combat Support Group

- 1985th Communications Squadron

- 554 CES (Red Horse - Combat Engineers)

U-Tapao USAF unit emblem gallery

Strategic Air Command

Strategic Air Command

1966–1975 3d Air Division

3d Air Division

1966–1970 8th Air Force

8th Air Force

1970–1975 7th Bomb Wing

7th Bomb Wing 22d Bomb Wing

22d Bomb Wing 28th Bomb Wing

28th Bomb Wing 70th Bomb Wing

70th Bomb Wing 91st Bomb Wing

91st Bomb Wing 92d Bomb Wing

92d Bomb Wing 93d Bomb Wing

93d Bomb Wing 96th Bomb Wing

96th Bomb Wing 99th Bomb Wing

99th Bomb Wing 306th Bomb Wing

306th Bomb Wing 454th Bomb Wing

454th Bomb Wing 461st Bomb Wing

461st Bomb Wing 509th Bomb Wing

509th Bomb Wing

See also

- United States Air Force in Thailand

- United States Pacific Air Forces

- Strategic Air Command

- Eighth Air Force

References

- ↑ Airport information for VTBU at World Aero Data. Data current as of October 2006.Source: DAFIF.

- ↑ Airport information for UTP at Great Circle Mapper. Source: DAFIF (effective October 2006).

- ↑ EXCLUSIVE: Sources Tell ABC News Top Al Qaeda Figures Held in Secret CIA Prisons – ABC News

- ↑ (in Thai) ต้นโพธิ์ทรงปลูกรอดพายุ พระเทพฯ ทรงห่วงพม่า, Thai Rath, 9 May 2008

- ↑ JTF Caring Response News Story

- ↑ USAID Burma: Cyclone Nargis Archived 8 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Thailand rejects Nasa base request". News24. Reuters. 2012-06-26. Retrieved 20 January 2017.

- ↑ http://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2015/06/us-military-bases-around-the-world-119321

- ↑ "Thai airfield is dedicated, built by U.S.". The Morning Record. Meriden, CT. Associated Press. 11 August 1966. p. 10.

- ↑ Yared, Antoine (17 August 1966). "Thais quiet about U.S. use of bases". Eugene Register-Guard. Associated Press. p. 6B.

- ↑ "Bomber move sought by U.S.". Beaver County Times. Beaver, PA. UPI. 15 October 1970. p. A11.

- ↑ "Thailand: A Plum". Reading Eagle. Associated Press. 11 September 1966. p. 20.

- ↑ "1955 USAF serial numbers". Joseph F. Baugher. Retrieved 1 August 2014.

- ↑ Accident description for 55-3138 at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 1 August 2014.

- ↑ "USAF tanker crashes on way to war planes". Virgin Islands Daily News. Associated Press. 3 October 1968. p. 4.

- ↑ "084 Accident description". Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved 21 August 2010.

- ↑ "year 1975 accidents". Helicopter Accidents. 23 December 2013.

1975 CH-53C 65-262 US Air Force 68-10933 : USAF; 21st SOS w/o 13may75 Udorn, Thailand

- ↑ Marks, Frederick H. (14 May 1975). "Thai leaders protest arrival of U.S. marines". Bryan Times. Bryan, Ohio. UPI. p. 1.

- ↑ "U.S. to begin pullout of troops from Thailand". Miami News. 5 May 1975. p. 2A.

- ↑ "Many Thais saddened by U.S. military withdrawals". Nashua Telegraph. UPI. 3 December 1975. p. 42.

- ↑ Dawson, Alan (21 June 1976). "U.S. out of Thailand". Beaver County Times. Beaver, Pennsylvania. UPI. p. A3.

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from the Air Force Historical Research Agency website http://www.afhra.af.mil/.

This article incorporates public domain material from the Air Force Historical Research Agency website http://www.afhra.af.mil/.

- Endicott, Judy G. (1999) Active Air Force wings as of 1 October 1995; USAF active flying, space, and missile squadrons as of 1 October 1995. Maxwell AFB, Alabama: Office of Air Force History. CD-ROM.

- Glasser, Jeffrey D. (1998). The Secret Vietnam War: The United States Air Force in Thailand, 1961–1975. McFarland & Company. ISBN 0-7864-0084-6.

- Martin, Patrick (1994). Tail Code: The Complete History of USAF Tactical Aircraft Tail Code Markings. Schiffer Military Aviation History. ISBN 0-88740-513-4.

- Ravenstein, Charles A. (1984). Air Force Combat Wings Lineage and Honors Histories 1947–1977. Maxwell AFB, Alabama: Office of Air Force History. ISBN 0-912799-12-9.

- USAAS-USAAC-USAAF-USAF Aircraft Serial Numbers—1908 to present

- The Royal Thai Air Force (English Pages)

- Royal Thai Air Force – Overview

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to U-Tapao Royal Thai Navy Airfield. |

- Utapao Royal Thai Airbase mid-summer 1971 unit history

- U-Tapao Royal Thai Navy Airfield history

- 635 Supply Chain Operations Wing fact sheet — successor to 635 Combat Support Group

- U-Tapao – history, photos, maps, etc.

- YouTube.com – video – U-Tapao 1969

- YouTube.com – video – U-Tapao Buff Launch – (early 1970s)

- The short film STAFF FILM REPORT 66-17A (1966) is available for free download at the Internet Archive