Natalizumab

| Monoclonal antibody | |

|---|---|

| Type | Whole antibody |

| Source | Humanized (from mouse) |

| Target | alpha-4 integrin |

| Clinical data | |

| Trade names | Tysabri |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a605006 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of administration | Intravenous infusion |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | n/a |

| Biological half-life | 11 ± 4 days |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider |

|

| UNII | |

| ChEMBL | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Molar mass | 149 g/mol |

| | |

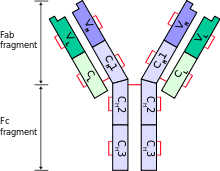

Natalizumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody against the cell adhesion molecule α4-integrin. Natalizumab is used in the treatment of multiple sclerosis and Crohn's disease. It is co-marketed by Biogen and Élan as Tysabri, and was previously named Antegren. Natalizumab is administered by intravenous infusion every 28 days. The drug is believed to work by reducing the ability of inflammatory immune cells to attach to and pass through the cell layers lining the intestines and blood–brain barrier. Natalizumab has proven effective in treating the symptoms of both diseases, preventing relapse, vision loss, cognitive decline and significantly improving quality of life in people with multiple sclerosis, as well as increasing rates of remission and preventing relapse in Crohn's disease.

Natalizumab was approved in 2004 by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). It was subsequently withdrawn from the market by its manufacturer after it was linked with three cases of the rare neurological condition progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) when administered in combination with interferon beta-1a, another immunosuppressive drug often used in the treatment of multiple sclerosis. After a review of safety information and no further deaths, the drug was returned to the US market in 2006 under a special prescription program. As of June 2009, ten cases of PML were known. However, twenty-four cases of PML had been reported since its reintroduction by October 2009, showing a sharp rise in the number of fatalities and prompting a review of the chemical for human use by the European Medicines Agency.[1][2][3] By January 2010, 31 cases of PML were attributed to natalizumab.[4] The FDA did not withdraw the drug from the market because its clinical benefits outweigh the risks involved.[5] In the European Union, it has been approved for human use only for the treatment of multiple sclerosis and only then as a monotherapy because the initial cases of PML, and later the fatalities, were said by the manufacturers to be linked to the use of previous medicines by the patients.

Biogen Idec announced the initiation of the first clinical trial of natalizumab as a potential cancer treatment as of September 5, 2008.[6]

Indications

Natalizumab is FDA-approved for the treatment of multiple sclerosis and Crohn's disease and approved for treatment of multiple sclerosis in Europe.[7][8] Pre-clinical evidence suggests that it could be also used in combination for the treatment of B-cell malignancies where it overcomes the resistance to rituximab.[9]

Multiple sclerosis

Natalizumab was evaluated in two randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials in people with multiple sclerosis. The studies enrolled individuals with MS who experienced at least one clinical relapse during the prior year and had a Kurtzke EDSS score between 0 and 5. In these trials natalizumab was shown to reduce relapses in individuals with MS by 68% vs. placebo, a margin far greater than had been seen for other approved MS therapies.[10] Natalizumab also slowed the progression of disability in patients with relapsing MS.[10][11] In combination with interferon beta-1a (IB1A), relapsing and disability progression were reduced more than IB1A alone.[12] Other benefits of natalizumab use by patients with relapsing MS included reduced visual loss,[13] a significant increase in the proportion of disease-free individuals,[14] significantly improved assessments of health-related quality of life in relapsing individuals,[15][16] reduced cognitive decline of a portion of individuals with MS,[17] reduced hospitalizations and steroid use,[18] and prevention of the formation of new lesions.[10][19] Approximately 6% of individuals receiving natalizumab have been found to develop persistent antibodies to the drug, which reduces its efficacy[12][20][21] and produce reactions during the infusion of the drug, as well as hypersensitivity.[12] Natalizumab is approved in the United States and the European Union. It is indicated as monotherapy (not combined with other drugs) for the treatment of highly active relapsing remitting MS in spite of prior treatments.[11] Natalizumab offers a limited improvement in efficacy compared to other treatments for MS, but due to the lack of information about long-term use, as well as potentially fatal adverse events, reservations have been expressed over the use of the drug outside of comparative research with existing medications.[12]

Crohn's disease

Several randomized controlled trials have demonstrated that natalizumab is effective in increasing rates of remission[22] and maintaining symptom-free status[23] in patients with Crohn's disease. Natalizumab may be appropriate in patients who do not respond to medications that block tumor necrosis factor-alpha such as infliximab,[24] with some evidence to support combination treatment of Crohn's disease with natalizumab and infliximab may be helpful in inducing remission.[25] Treatment of adolescent patients with natalizumab demonstrates an effectiveness similar to that of adult patients.[26]

In January 2008, the FDA approved natalizumab for both induction of remission and maintenance of remission for moderate to severe Crohn's disease,[27] though it has not been approved for this use in the European Union due to concerns over its risk/benefit ratio.[28]

Adverse effects

Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, an opportunistic infection caused by the JC virus, and that only occurs in patients who are immunocompromised, has affected an estimated 212 patients as of 2012, or 2.1 in every 1,000 using natalizumab.[29] It was first observed in seven patients who received natalizumab in late 2008;[30] three cases were noted in clinical trials in 2006[31] leading to the drug being temporarily pulled from the market; two cases were reported to the FDA in August 2008;[32] and, two cases were announced in December 2008.[30] By January 21, 2010 the FDA noted a total of 31 confirmed cases of PML, with the chance of developing the infection increasing as the number of infusions received by a patient increased. Because of this association, the drug label and package insert accompanying the drug will be updated to include this information.[33] As of February 29, 2012, there were 212 confirmed cases of PML among 99,571 patients treated with natalizumab (2.1 cases per 1000 patients). All 54 patients with PML for whom samples were available before the diagnosis were positive for anti–JC virus antibodies. When the risk of PML was evaluated according to three risk factors, it was lowest among the patients who had used natalizumab for the shortest periods, those who had used few if any immunosuppressant drugs to treat MS in the past, and lastly who were negative for anti–JC virus antibodies. The incidence of PML in the low risk group was estimated to be 0.09 cases, or less, per 1000 patients. Patients who had taken natalizumab for longer, from 25 to 48 months, who were positive for anti–JC virus antibodies, had taken immunosuppressants before the initiation of natalizumab therapy had the highest risk of developing PML. Their risk is fully 123 times higher than the low risk group. (incidence, 11.1 cases per 1000 patients [95% CI, 8.3 to 14.5]).[29] While none of them had taken the drug in combination with other disease-modifying treatments, previous use of MS treatments increases the risk of PML between 3 and 4-fold.[34]

Postmarketing surveillance in early 2008 revealed that 0.1% of people taking natalizumab experience clinically significant liver injury, leading to the FDA, EMEA and manufacturers recommending that the medication be discontinued in patients with jaundice or other evidence of significant liver damage.[35][36][37] This rate is comparable to other immune-suppressing drugs.[38] Evidence of hepatotoxicity in the form of elevated blood levels of bilirubin and liver enzymes can appear as soon as six days after an initial dose; reactions are unpredictable and may appear even if the patient does not react to previous treatment.[39] Such signs reoccur upon rechallenge in some patients, indicating that damage is not coincidental.[39] In the absence of any blockage these liver function tests are predictors of severe liver injury with possible sequelae of liver transplantation or death.[39]

Common adverse effects include fatigue and allergic reactions with a low risk of anaphylaxis,[40] headache, nausea, colds and exacerbation of Crohn's disease in a minority of patients with the condition.[25] Adolescents with Crohn's disease experience headache, fever and exacerbation of Crohn's disease.[26] Natalizumab is contraindicated for people with known hypersensitivity to the drug or its components and in patients with a history of PML (see interactions).

Natalizumab has also been linked to melanoma, though the association is unclear.[41] The long-term effects of the drug are unknown[42] and concern has been expressed over the risks of infection and cancer.[12]

Mechanism of action

Natalizumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody against alpha-4 (α4) integrin, the first drug developed in the class of selective adhesion molecule inhibitors. α4-integrin is required for white blood cells to move into organs, and natalizumab's mechanism of action is believed to be the prevention of immune cells from crossing blood vessel walls to reach affected organs.[43]

In multiple sclerosis

The symptom-causing lesions of MS are believed to be caused when inflammatory cells such as T-lymphocytes pass through the blood–brain barrier through interaction with receptors on the endothelial cells. Natalizumab appears to reduce the transmission of immune cells into the central nervous system by interfering with the α4β1-integrin receptor molecules on the surfaces of cells. The effect appears to occur on endothelial cells expressing the VCAM-1 gene, and in parenchymal cells expressing the osteopontin gene. In animals used to model MS and test therapies, repeated administration of natalizumab reduced migration of leukocytes into the brain's parenchyma, and also reduced lesioning, though it is uncertain if this is clinically significant for humans.[44]

Individuals with MS dosed with natalizumab demonstrated increased CD34-expressing cells, with research suggesting a peak in expression after 72 hours.[45]

In Crohn's disease

The interaction of the α4β7 integrin and the addressin (also known as MADCAM1) endothelial cell receptor is believed to contribute to the chronic bowel inflammation that causes Crohn's disease. Addressin is primarily expressed in the endothelium of venules in the small intestine and are critical in guiding T-lymphocytes to lymphatic tissues in Peyer's patches. In CD patients, sites of active inflammation of the bowel in CD patients have increased expression of addressin, suggesting a connection between the inflammation and the receptor. Natalizumab may block interaction between the α4β7 integrin and addressin at sites of inflammation. Animal models have found higher levels of VCAM-1 expression in mice with irritable bowel syndrome and the VCAM-1 gene may also play a part in CD but its role is not yet clear.[44]

Interactions

Natalizumab appears to interact with other immune-modulating drugs to increase the risk of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML), an often-fatal opportunistic infection caused by the JC virus. In 2005, two people taking natalizumab in combination with interferon beta-1a developed PML. One died, and the other recovered with disabling sequelae.[46][47] A third fatal case initially attributed to an astrocytoma was reported in a patient being treated for Crohn's disease.[48] Though the patient was being treated with natalizumab in combination with azathioprine, corticosteroids and infliximab, indications of PML infection appeared only after natalizumab monotherapy was re-introduced.[48] No deaths from progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy have been linked to natalizumab when it was not combined with other immune-modulating drugs[49] and other rates of opportunistic infections are not increased in patients taking natalizumab[50] possibly due to the drug’s mechanism of action.[51] Other than a prior history of PML, there is no known method to identify patients at risk of developing PML.[52] Natalizumab's label indicates that it is contraindicated for immunosuppressed individuals or those with a history of PML.[44] Due to the uncertain risk of PML, natalizumab is only available through a restricted distribution program.[44] As of June 2009, ten cases of PML associated with natalizumab have been reported.[3] At least one of them had not previously taken any other inmunomodulator therapy.[53] By January 21, 2010 the United States Food and Drug Administration reported a total of 31 confirmed cases of PML associated with natalizumab.[4]

Though the small number of cases precludes conclusion on the ability of natalizumab alone to induce PML, its black box warning states that the drug has only been linked to PML when combined with other immune-modulating drugs and natalizumab is contraindicated for use with other immunomodulators.[44] Corticosteroids may produce immunosuppression, and the Tysabri prescribing information recommends that people taking corticosteroids for the treatment of Crohn's disease have their doses reduced before starting natalizumab treatment.[44] The risk of developing PML was later estimated to be 1 in 1,000 (0.1%) over 18 months[20][50][54] though the longer term risks of PML are unknown.[20]

Legal status

Natalizumab was originally approved for treatment of multiple sclerosis in 2004, through the FDA's accelerated Fast Track program, due to the drug's efficacy in one-year clinical trials. In February 2005, four months after its approval, natalizumab was withdrawn voluntarily by the manufacturer after two cases of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Groups representing individuals with MS lobbied to have the drug returned to the US market[55] and in June, 2006, after recommendation by an advisory committee and a review of two years of safety and efficacy data, the FDA re-approved natalizumab for patients with all relapsing forms of MS (relapse-remitting, secondary-progressive, and progressive-relapsing) as a first-line or second-line therapy.[56][57] Patients taking natalizumab must enter into a registry for monitoring.[55] Natalizumab is the only drug after alosetron withdrawn for safety reasons that returned to the US market.

In April, 2006 the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use recommended authorizing natalizumab to treat relapsing-remitting MS, and several weeks later the European Medicines Agency approved natalizumab in the European Union for highly-active relapsing remitting MS.[8]

Health Canada added natalizumab to Schedule F of the Food and Drug Regulations on April 3, 2008 as a prescription drug requiring oversight from a physician.[58]

References

- ↑ "Meeting highlights from the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use" (pdf). European Medicines Agency. 2009-10-22. Retrieved 2010-08-31.

- ↑ Hirschler, B; Cowell D (2009-10-29). "EU agency reports 24th case of Tysabri infection". Reuters. Retrieved 2010-08-31.

- 1 2 Clarke T, Orlofsky S, Von Ahn L (2009-06-29). "Biogen reports 10th case of PML brain infection". Reuters. Retrieved 2010-08-31.

- 1 2 Jeffrey, S (2010-02-05). "PML Risk Increases With Repeated Natalizumab Infusions: FDA". Medscape. Retrieved 2010-08-31.

- ↑ Hitti, M (2008-08-01). "MS Drug Tysabri Tied to Brain Infection". WebMD. Retrieved 2010-08-31.

- ↑ "Biogen Idec testing Tysabri as a cancer treatment". The Boston Globe. 2008-09-05. Retrieved 2008-09-05.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2009-11-10.

- 1 2 "Press release - European Medicines Agency: Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use 24–27 April 2006" (PDF). European Medicines Agency. 2006-04-28. Retrieved 2008-04-02.

- ↑ Mraz, M.; Zent, C. S.; Church, A. K.; Jelinek, D. F.; Wu, X.; Pospisilova, S.; Ansell, S. M.; Novak, A. J.; Kay, N. E.; Witzig, T. E.; Nowakowski, G. S. (2011). "Bone marrow stromal cells protect lymphoma B-cells from rituximab-induced apoptosis and targeting integrin α-4-β-1 (VLA-4) with natalizumab can overcome this resistance". British Journal of Haematology. 155 (1): 53–64. PMC 4405035

. PMID 21749361. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.2011.08794.x.

. PMID 21749361. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.2011.08794.x. - 1 2 3 Polman CH, O'Connor PW, Havrdova E, et al. (2006). "A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of natalizumab for relapsing forms of multiple sclerosis". N. Engl. J. Med. 354 (9): 899–910. PMID 16510744. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa044397.

- 1 2 "TYSABRI: ANNEX I – SUMMARY OF PRODUCT CHARACTERISTICS" (PDF). European Medicines Agency. Retrieved 2008-03-09.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Natalizumab: new drug. Multiple sclerosis: risky market approval". Prescrire Int. 17 (93): 7–10. 2008. PMID 18354844.

- ↑ Balcer LJ, Galetta SL, Calabresi PA; et al. (2007). "Natalizumab reduces visual loss in patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis". Neurology. 68 (16): 1299–304. PMID 17438220. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000259521.14704.a8.

- ↑ Galetta, S; et al. (2008-04-18). "Natalizumab Increases the Proportion of Patients Free of Clinical or MRI Disease Activity in Relapsing Multiple Sclerosis". unpublished/unpresented conference poster. Retrieved 2008-03-11.; industry publication - "New TYSABRI Data to Be Presented at the European Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis". Élan. 2007-10-11. Archived from the original on 2007-10-29. Retrieved 2008-03-09.

- ↑ Rudick RA, Miller DM (2008). "Health-related quality of life in multiple sclerosis : current evidence, measurement and effects of disease severity and treatment". CNS Drugs. 22 (10): 827–39. PMID 18788835. doi:10.2165/00023210-200822100-00004.

- ↑ Rudick RA, Miller D, Hass S; et al. (2007). "Health-related quality of life in multiple sclerosis: effects of natalizumab". Ann. Neurol. 62 (4): 335–46. PMID 17696126. doi:10.1002/ana.21163.

- ↑ "New Data on Natalizumab Demonstrate Significant Improvement in Cognitive Function in Patients With Multiple Sclerosis". Doctor's Guide. 2006-09-28. Retrieved 2008-03-09.

- ↑ "New Pharmacoeconomic Data On TYSABRI Demonstrate Significant Reduction In Steroid Use And Hospitalizations In Patients With Multiple Sclerosis". webwire. 2006-10-06. Retrieved 2008-03-09.

- ↑ Miller DH, Soon D, Fernando KT; et al. (2007). "MRI outcomes in a placebo-controlled trial of natalizumab in relapsing MS". Neurology. 68 (17): 1390–401. PMID 17452584. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000260064.77700.fd.

- 1 2 3 Hutchinson M (2007). "Natalizumab: A new treatment for relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis". Ther Clin Risk Manag. 3 (2): 259–268. PMC 1936307

. PMID 18360634. doi:10.2147/tcrm.2007.3.2.259.

. PMID 18360634. doi:10.2147/tcrm.2007.3.2.259. - ↑ Calabresi PA, Giovannoni G, Confavreux C; et al. (2007). "The incidence and significance of anti-natalizumab antibodies: results from AFFIRM and SENTINEL". Neurology. 69 (14): 1391–403. PMID 17761550. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000277457.17420.b5.

- ↑ Ghosh S, Goldin E, Gordon F, Malchow H, Rask-Madsen J, Rutgeerts P, Vyhnálek P, Zádorová Z, Palmer T, Donoghue S (2003). "Natalizumab for active Crohn's disease". N. Engl. J. Med. 348 (1): 24–32. PMID 12510039. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa020732.

- ↑ Feagan BG, Sandborn WJ, Hass S, Niecko T, White J (2007). "Health-related quality of life during natalizumab maintenance therapy for Crohn's disease". Am. J. Gastroenterol. 102 (12): 2737–46. PMID 18042106. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01508.x.

- ↑ Michetti P, Mottet C, Juillerat P, et al. (2007). "Severe and steroid-resistant Crohn's disease". Digestion. 76 (2): 99–108. PMID 18239400. doi:10.1159/000111023.

- 1 2 Sands BE, Kozarek R, Spainhour J, et al. (2007). "Safety and tolerability of concurrent natalizumab treatment for patients with Crohn's disease not in remission while receiving infliximab". Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 13 (1): 2–11. PMID 17206633. doi:10.1002/ibd.20014.

- 1 2 Hyams JS, Wilson DC, Thomas A, et al. (2007). "Natalizumab therapy for moderate to severe Crohn disease in adolescents". J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 44 (2): 185–91. PMID 17255829. doi:10.1097/01.mpg.0000252191.05170.e7.

- ↑ "FDA Approves Tysabri to Treat Moderate-to-Severe Crohn's Disease". Food and Drug Administration. 2008-01-14. Retrieved 2008-03-09.

- ↑ "Refusal CHMP assessment report for natalizumab" (PDF). European Medicines Agency. 2007-11-15. Retrieved 2008-04-02. "lay-summary" (PDF). (78.5 KB)

- 1 2 Bloomgren, Gary; Richman, Sandra; Hotermans, Christophe; Subramanyam, Meena; Goelz, Susan; Natarajan, Amy; Lee, Sophia; Plavina, Tatiana; Scanlon, James V.; Sandrock, Alfred; Bozic, Carmen (2012). "Risk of Natalizumab-Associated Progressive Multifocal Leukoencephalopathy". New England Journal of Medicine. 366 (20): 1870–1880. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 22591293. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1107829.

- 1 2 Greene, Robert T. (December 15, 2008). "Biogen, Elan Report Brain Illness in Tysabri Patient". Bloomberg.com. Retrieved December 21, 2008.

- ↑ Van Assche G, Van Ranst M, Sciot R, et al. (July 2005). "Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy after natalizumab therapy for Crohn's disease". N. Engl. J. Med. 353 (4): 362–8. PMID 15947080. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa051586.

- ↑ U.S. Food and Drug Administration (August 2008). "Natalizumab Injection for Intraveneous {{sic}} Use (marketed as Tysabri)". Archived from the original on December 19, 2008. Retrieved December 22, 2008.

- ↑ "FDA Drug Safety Communication: Risk of Progressive Multifocal Leukoencephalopathy (PML) with the use of Tysabri (natalizumab)". FDA. 2010-05-02. Retrieved 2010-08-31.

- ↑ Kappos L, Bates D, Edan G, Eraksoy M, Garcia-Merino A, Grigoriadis N, Hartung HP, Havrdová E, Hillert J, Hohlfeld R, Kremenchutzky M, Lyon-Caen O, Miller A, Pozzilli C, Ravnborg M, Saida T, Sindic C, Vass K, Clifford DB, Hauser S, Major EO, O'Connor PW, Weiner HL, Clanet M, Gold R, Hirsch HH, Radü EW, Sørensen PS, King J (August 2011). "Natalizumab treatment for multiple sclerosis: updated recommendations for patient selection and monitoring.". Lancet neurology. 10 (8): 745–58. PMID 21777829. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70149-1.

- ↑ "FDA MedWatch - 2008 Safety Information Alerts". Food and Drug Administration. 2008-02-28. Retrieved 2008-04-05.

- ↑ "EMEA concludes new advice to doctors and patients for Tysabri (natalizumab) needed" (PDF). European Medicines Agency. 2008-03-20. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 18, 2009. Retrieved 2008-04-05.

- ↑ "Questions and answers on Tysabri and liver injury" (PDF). European Medicines Agency. 2008-03-20. Retrieved 2008-04-14. ; lay-summary Archived June 11, 2008, at the Wayback Machine., second summary Archived December 5, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Kenneth Gross, M.D. (2008-03-03). "Multiple Sclerosis - Natalizumab (Tysabri) Can Rarely Cause Liver Problems". Retrieved 2008-04-05.

- 1 2 3 Panzara, M; Francis V (2008-02-01). "Important safety information: Dear Healthcare Practitioner letter" (PDF). Biogen Idec and Élan. Retrieved 2008-04-11.; lay summary Archived June 11, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Horga A, Horga de la Parte JF (2007). "[Natalizumab in the treatment of multiple sclerosis]". Rev Neurol (in Spanish). 45 (5): 293–303. PMID 17876741.

- ↑ Mullen JT, Vartanian TK, Atkins MB (2008). "Melanoma complicating treatment with natalizumab for multiple sclerosis". N. Engl. J. Med. 358 (6): 647–8. PMID 18256405. doi:10.1056/NEJMc0706103.

- ↑ van Bronswijk H, Dubois EA, van Gerven JM, Cohen AF (2008). "[New drugs; natalizumab]". Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd (in Dutch and Flemish). 152 (9): 499–500. PMID 18389881.

- ↑ Rice GP, Hartung HP, Calabresi PA (2005). "Anti-alpha4 integrin therapy for multiple sclerosis: mechanisms and rationale". Neurology. 64 (8): 1336–42. PMID 15851719. doi:10.1212/01.WNL.0000158329.30470.D0.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Final TYSABRI PI" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on August 22, 2007. Retrieved 2008-03-13.

- ↑ Zohren F, Toutzaris D, Klarner V, Hartung HP, Kieseier B, Haas R (2008). "The monoclonal anti-VLA4 antibody natalizumab mobilizes CD34+ hematopoietic progenitor cells in humans". Blood. 111 (7): 3893–5. PMID 18235044. doi:10.1182/blood-2007-10-120329.

- ↑ Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK, Tyler KL (2005). "Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy complicating treatment with natalizumab and interferon beta-1a for multiple sclerosis". N. Engl. J. Med. 353 (4): 369–74. PMID 15947079. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa051782.

- ↑ Langer-Gould A, Atlas SW, Green AJ, Bollen AW, Pelletier D (2005). "Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in a patient treated with natalizumab". N. Engl. J. Med. 353 (4): 375–81. PMID 15947078. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa051847.

- 1 2 Van Assche G, Van Ranst M, Sciot R, et al. (2005). "Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy after natalizumab therapy for Crohn's disease". N. Engl. J. Med. 353 (4): 362–8. PMID 15947080. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa051586.

- ↑ Yousry TA, Major EO, Ryschkewitsch C; et al. (2006). "Evaluation of patients treated with natalizumab for progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy". N. Engl. J. Med. 354 (9): 924–33. PMC 1934511

. PMID 16510746. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa054693.

. PMID 16510746. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa054693. - 1 2 Berger JR (2006). "Natalizumab". Drugs Today. 42 (10): 639–55. PMID 17136224. doi:10.1358/dot.2006.42.10.1042190.

- ↑ Ransohoff RM (2007). ""Thinking without thinking" about natalizumab and PML". J. Neurol. Sci. 259 (1–2): 50–2. PMID 17521672. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2006.04.011.

- ↑ Aksamit AJ (2006). "Review of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy and natalizumab". Neurologist. 12 (6): 293–8. PMID 17122725. doi:10.1097/01.nrl.0000250948.04681.96.

- ↑ Goldstein, Jacob (2008-08-01). "Brain Infections Return for Multiple Sclerosis Drug Tysabri". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 2008-08-01.

- ↑ Kappos L, Bates D, Hartung HP, et al. (2007). "Natalizumab treatment for multiple sclerosis: recommendations for patient selection and monitoring". Lancet Neurol. 6 (5): 431–41. PMID 17434098. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70078-9.

- 1 2 Pollack, A (2006-03-09). "F.D.A. Panel Recommends M.S. Drug Despite Lethal Risk". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-03-13.

- ↑ "Errata to FDA Background document for the Tysabri (natalizumab) Advisory Committee on July 31, 2007" (PDF). Food and Drug Administration. 2007-07-20. Retrieved 2008-03-09.

- ↑ Fiore D (2007). "Multiple sclerosis and natalizumab". Am J Ther. 14 (6): 555–60. PMID 18090880. doi:10.1097/MJT.0b013e31804bfa6a.

- ↑ "SOR/2008-101: Food and Drug Act; Regulations Amending the Food and Drug Regulations (1528—Schedule F)" (PDF). Canada Gazette Part I. 142 (8): 649. 2008-04-16.