Tyrol

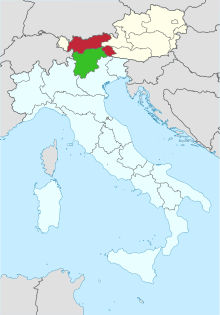

Tyrol (historically the Tyrole,[1][2][3] German: Tirol, Italian: Tirolo) is a historical region in the Alps; in northern Italy and western Austria.

Etymology

According to Egon Kühebacher, the name Tyrol derives from a root word meaning terrain (i.e. area, ground or soil; compare Latin: terra and Old Irish: tir); first from the village of Tirol, and its castle; from which the County of Tyrol grew.[4] According to Karl Finsterwalder, the name Tyrol derives from Teriolis, a late-Roman fort and travellers' hostel in Zirl, Tyrol.[5] There seems to be no scholarly consensus.

History

Prehistory

The earliest archaeological records of human settlement in Tyrol have been found in the Tischofer Cave. They date from the Palaeolithic, about 28,000-27,000 BP. The same cave has also yielded evidence of human occupation during the Bronze Age (very roughly, 4000-3000 BP (2000-1000 BC)).

In 1991, the mummified remains of a man who had died around 3300-3100 BC were discovered in a glacier in the Ötztal Alps, in Tyrol. Researchers have called him Ötzi (and also other names, including "The Iceman"). He lived during the Chalcolithic or Copper Age, after man had learned how to exploit copper but before man had learned how to make bronze. His body and belongings were very well-preserved, and have been subjected to detailed scientific study. They are preserved in the South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology, Bolzano, South Tyrol, Italy.

There is evidence that Tyrol was a centre for copper mining in the 4th millennium BC; for example, at Brixlegg. There is also evidence of the Urnfield culture (roughly 1300-750 BC).

Evidence of the La Tène culture (roughly 450-100 BC, during the Iron Age) has also been found; as has evidence of the Fritzens-Sanzeno culture from about the same period. Towards the end of that time, Tyrol began to be noted in Roman written records. The inhabitants may have been Illyrians, in the process of being displaced by Celts (perhaps themselves displaced from Noricum by Slavs). There are also indications that Adriatic Veneti may have been present in the south of the region. The Romans called them Rhaetians; although it is not clear whether that then meant a specific tribe or confederation of tribes, or was a broader term for the inhabitants of the area. They made wine barrels (an idea which the Romans took from them), and had their own alphabet.

Roman times

In 15 BC, Tyrol was conquered by Roman forces commanded by Drusus and Tiberius. The Romans established Raetia and Noricum as provinces of the Roman Empire. Raetria included Vinschgau, Burggrafenamt, Eisacktal, Wipptal, Oberinntal and parts of the Unterinntal. Noricum included Pustertal, Defereggen and parts of the Unterinntal to the right of the Ziller and the Inn. Bolzano and the extreme south of Tyrol belonged to the province of Venetia et Histria.

The inhabitants adopted vulgar Latin, and combined it with their own languages. The result was Romansh, which is still spoken today and is one of the official languages of Switzerland.

The Romans constructed metalled roads guarded by forts through Tyrol to connect the Italian peninsula and the lands beyond; notably the Via Claudia Augusta and the Via Raetia. The Romans did not seem to find Tyrol an attractive area in which to build new towns, because there are few of them. One town they did build was Aguntum, near modern Lienz.

In late antiquity (from 476 AD), Tyrol belonged to the Ostrogoths, and it was included in the Ostrogothic Kingdom. In 534, the Ostrogoths lost Merrano, Val Venosta and Passer to the Franks. The Ostrogothic Kingdom collapsed in 553, after being overrun by Bajuvarians from the north and Lombards from the south. The Lombards established the Duchy of Tridentum (or, Trent; roughly corresponding to modern Trentino) in south Tyrol. Slavic peoples, who had recently taken Carinthia from the Bajuvarians, settled in east Tyrol.

Middle Ages

Most of Tyrol came under the control of the Duchy of Bavaria (created c. 555). The southern parts, including Bolzano, Salorno, and the right bank of the Adige (including Eppan and Kaltern) remained under the Lombards. Tyrol was christianised through the bishoprics of Brixen and Triento. The frontier remained the same though Carolingian and Ottonian times. The area was subject to Stammensgerechte (Ancient Germanic laws), such as Lex Romana Curiensis (see Raetia Curiensis), Lex Alamannorum, Lex Baiuvariorum and Leges Langobardorum.

In 1027, Emperor Conrad II, in order to secure the important route through the Brenner Pass, allotted the left bank of the Adige (from Lana to Mezzocorona) to the Duchy of Bavaria. During the 12th century, the local nobility went further: they built Tyrol Castle in the modern comune of Tirol in South Tyrol, near modern Merano; and around 1140, established the County of Tyrol as a state within the Holy Roman Empire.

The Counts of Tyrol were at first Vogt (underlords) subject to the Bishoprics of Brixen and Triento; but they had other ideas. They expanded their holdings at those bishoprics' expense. They displaced competing nobles like the House of Eppan, and declared their independence from the Duchy of Bavaria; though not without dispute. In 1228, they conceded the Saalforste to the House of Wittelsbach, rulers of Bavaria; as a result, that area remains part of Bavaria to this day.

In 1253, rulership of the County passed by inheritance to the Meinhardiner family. In 1335, the last male heir to the Meinhardiner lands, Henry of Bohemia, died. His daughter, Margaret, thereupon became Countess of Tyrol; but her title was in doubt because of different laws in different lands as to what a woman could or could not inherit. She navigated her way between the competing claims of the Houses of Wittelsbach, Luxembourg and Habsburg by, in 1342, marrying Louis of Wittelsbach. Louis died in 1361. Margaret died in 1369, and bequeathed Tyrol to Rudolf of Habsburg. The various dynastic squabbles were resolved that same year by the Treaty of Schärding, under which (for suitable compensation) the Wittelsbachs agreed to relinquish their claims to Tyrol in favour of the Habsburgs.

When the Habsburgs took control of Tyrol, it had roughly its modern size. However, the Unterinntal downstream from Schwaz still belonged to Bavaria; the Zillertal and Brixental to Salzburg; Brixen and the Pustertal were episcopal territories, or part of the County of Gorizia. Therefore, the Montafon and the Unterengadin were Tyrolean.

Tyrol was of great strategic importance to the Habsburgs. It controlled several important Alpine passes. It connected their landholdings in Further Austria. In 1406, as the Habsburg lands were split up by inheritance, Tyrol once again became a separate entity (a Landstand), in which the greater landowners had the right to be consulted (Mitspracherecht). During a confusing succession of events, in 1420 Frederick IV, Duke of Austria moved the capital of Tyrol from Meran to Innsbruck, and Meran lost its earlier importance.

Heraldry

- See Coat of arms of Tyrol

Although the details of the arms of Tyrol have changed over the centuries, one feature has remained more-or-less constant: argent, an eagle displayed gules, armed (and sometimes crowned) or.[6]

References

- ↑ , p. PA159, at Google Books

- ↑ "PressReader.com - Zeitungen aus der ganzen Welt". pressreader.com (in German). Retrieved 2017-07-19.

- ↑ , p. PA1, at Google Books

- ↑ Kühebacher, Egon (1991). Die Ortsnamen Südtirols und ihre Geschichte. Die geschichtlich gewachsenen Namen der Gemeinden, Fraktionen und Weiler (in German). Bolzano: Athesia. pp. 470–471. ISBN 88-7014-634-0.

- ↑ Finsterwalder, Karl (1990). "Besprechung zu C. Battisti – G. Giacomelli, I nomi locali del Burgraviato di Merano". Tiroler Ortsnamenkunde. Gesammelte Aufsätze und Arbeiten (in German). 3. Innsbruck: Wagner. p. 1127. ISBN 3-7030-0279-4.

- ↑ Fox-Davies, A. C. (1909). A Complete Guide to Heraldry. Thomas Nelson and Sons Ltd. pp. 234–235.