Type 56 assault rifle

| Chinese Norinco Type 56 | |

|---|---|

|

The Type 56 with a spike bayonet | |

| Type | Assault rifle |

| Place of origin | China |

| Service history | |

| In service | 1956–present |

| Used by | See Users |

| Wars |

Indo pakistani warsVietnam War Cambodian Civil War Soviet–Afghan War Iran–Iraq War Sri Lankan Civil War Croatian War Bosnian War Kosovo War Syrian Civil War |

| Production history | |

| Designed | 1947 |

| Manufacturer |

|

| Produced | 1956–present |

| No. built | 10–15 million[1] |

| Variants | Type 56 Assault Rifle, Type 56-1 Assault Rifle, Type 56-2 Assault Rifle, Type 56-4 Assault Rifle QBZ-56C Assault Rifle, Type 56S, Type 84S rifle |

| Specifications | |

| Weight |

Type 56: 4.03 kg (8.88 lb) Type 56-1: 3.70 kg (8.16 lb) Type 56-2/56-4: 3.9 kg (8.60 lb) QBZ-56C: 2.85 kg (6.28 lb) |

| Length |

Type 56: 874 mm (34.4 in) Type 56-1/56-2: 874 mm (34.4 in) w/ stock extended,654 mm (25.7 in) w/ stock folded. QBZ-56C: 764 mm (30.1 in) w/ stock extended,557 mm (21.9 in) w/ stock folded. |

| Barrel length |

Type 56, Type 56-I, Type 56-II: 414 mm (16.3 in) QBZ-56C: 280 mm (11.0 in) |

|

| |

| Cartridge | 7.62×39mm |

| Caliber | 7.62mm |

| Action | Gas-operated, rotating bolt |

| Rate of fire | 650 rounds/min [2] |

| Muzzle velocity |

Type 56, Type 56-I, Type 56-II: 735 m/s (2,411 ft/s) QBZ-56C: 665 m/s (2182 ft/s) |

| Effective firing range | 100–800 m sight adjustments. Effective range 300-400 meters |

| Feed system | 20, 30, or 40-round detachable box magazine |

| Sights | Adjustable Iron sights |

The Chinese Norinco Type 56 is a Chinese 7.62×39mm assault rifle. It is a variant of the Soviet-designed AK-47 and AKM assault rifles.[3] Production started in 1956 at State Factory 66, and since then it has been produced by Norinco, who continue to produce the rifle primarily for export.

Service history

During the Cold War period, the Type 56 was exported to many countries and guerrilla forces throughout the world. Many of these rifles found their way to battlefields in Africa, Southeast Asia, and the Middle East and were used alongside other Kalashnikov pattern weapons from both the Soviet Union as well the Warsaw Pact nations of Eastern Europe.

Chinese support for the Democratic Republic of Vietnam before the mid-1960s meant that the Type 56 was frequently encountered by American soldiers in the hands of either Vietcong guerrillas or PAVN soldiers during the Vietnam war. The Type 56 was discovered in enemy hands far more often than standard Russian-made AK-47s or AKMs.[4]

When relations between China and the North Vietnam crumbled in the 1970s and the Sino-Vietnamese War began, the Vietnamese government still had large numbers of Type 56 rifles in its arsenals, while the People's Liberation Army still used the Type 56 as its standard weapon. Thus, Chinese and Vietnamese forces fought each other using the same Type 56 rifles.

The Type 56 was used extensively by Iranian forces during the Iran–Iraq War of the 1980s, with Iran purchasing large quantities of weapons from China for their armed forces. During the war, Iraq also purchased a small quantity, despite them being a major recipient of Soviet weapons and assistance during the war. This was done in conjunction with their purchasing of large number of AKMs from the USSR and Eastern Europe. Consequently, the Iran–Iraq War became another conflict in which both sides used the Type 56.

Since the end of the Cold War, the Type 56 has been used in many conflicts by various military forces. During the Croatian War of Independence and the Yugoslav Wars, it was used by the armed forces of Croatia. During the late 1990s, the Kosovo Liberation Army in Kosovo were also major users of the Type 56, with the vast majority of the weapons originating from People's Socialist Republic of Albania, which received Chinese support during much of the Cold War.

In the United Kingdom and the United States, the Type 56 and its derivatives are frequently used in the filming of movies and television shows, standing in for Russian-made AK-47s due to the rarity of original AK-47s, with some even being visually modified to resemble other AK-series rifles. Versions of this weapon that have the full-auto firing ability deleted (referred to as "sporter" rifles) are also available for civilian ownership in most parts of the United States.

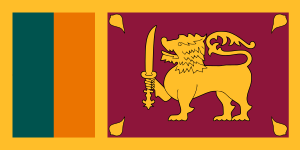

In the mid-1980s, Sri Lanka started to replace their L1A1 Self-Loading Rifles (SLR) and HK G3s with the Type 56. Currently, they use the fixed stock, under-folding stock and side-folding stock variants.

The Type 81, Type 95 and Type 03 replaced Type 56 in PLA front line service, but the Type 56 remains in use with reserve and militia service. Type 56s are still in production by Norinco for export customers.

During the Soviet war in Afghanistan in the 1980s, many Chinese Type 56 rifles were supplied to Afghan Mujahideen guerrillas to fight Soviet forces by the China, Pakistan and the US who obtained them from third party arms dealers.[5]

_during.jpg)

Use of the Type 56 in Afghanistan also continued well into the 1990s and the early 21st century as the standard rifle of the Taliban. When Taliban forces seized control of Kabul in 1996 (a majority of the Chinese small arms used by the Taliban were provided by Pakistan).[4]

Since the overthrow of the Taliban by U.S.-led Coalition forces in late 2001, the Chinese Type 56 assault rifle has been utilized by the Afghan National Army, with many rifles serving alongside other AK-47 and AKM variant rifles.

The Type 56 has been seen regularly in the hands of militants from the Izz ad-Din al-Qassam Brigades, the armed wing of Hamas in the Palestinian territories.

The Type 56 has been used by the Janjaweed in the Darfur region of Sudan with pictures and news footage showing members of the Janjaweed carrying Type 56 rifles (most of them provided by the Sudanese government).

In 1987, Michael Ryan used a legally owned Type 56 rifle, and two other firearms, in the Hungerford massacre in the United Kingdom, in which he shot 32 people, 17 of whom died. The attack led to the passage of Firearms (Amendment) Act 1988, which bans ownership of semi-automatic centre-fire rifles and restricts the use of shotguns.[6]

In the United States, a Type 56 rifle, purchased in Oregon under a false name,[7] was used in the 1989 Stockton schoolyard shooting in which Patrick Purdy fired over 100 rounds to shoot one teacher and 34 children, killing five. The shooting led to the passage of California's Roberti-Roos Assault Weapons Control Act of 1989.[8] A Type 56, along with a Type 56 S-1, were used by Larry Phillips, Jr. and Emil Mătăsăreanu during the North Hollywood shootout.[9]

In the Syrian Civil War of 2011 to the present, the Type 56 assault rifles are seen being used by the Free Syrian Army.

Compared to AK-47 and AKM

Originally, the Type 56 was a direct copy of the AK-47, and featured a milled receiver, but starting in the mid-1960s, the guns were manufactured with stamped receivers much like the Soviet AKM. Visually, most versions of the Type 56 are distinguished from the AK-47 and AKM by the fully enclosed hooded front sight (all other AK pattern rifles, including those made in Russia, have a partially open front sight). Many versions also feature a folding bayonet attached to the barrel just aft of the muzzle. There are three different types of bayonets made for Type 56 rifles. The first type 56s were near identical copies of the Soviet milled AK-47. It is speculated that the Chinese had to reverse engineer a copy of the AKM with the stamped receiver as they were not given a licence to produce the AKM and RPK by the Soviets because of failing relations after the Sino-Soviet split.

- The Type 56 has a 1.5mm stamped receiver (like the RPK, although it lacks the reinforced trunnion of the RPK) versus the 1mm stamping of the AKM.

- The barrel on the Type 56 is similar to the AK-47 and heavier than that of the AKM.

- The front sights are fully enclosed, compared to the AKM and AK-47 which are partially opened.

- Has the double hook disconnector of the AK-47 rather than the single hook disconnector of the AKM.

- Has a smooth dust cover like the AK-47 and unlike the ribbed dust cover of the AKM.

- May have a folding spike bayonet (nicknamed the "pig sticker") as opposed to the detachable knife bayonets of the AK-47 and AKM. There are three different types of spike bayonets made for Type 56 rifles. Type 56 assault rifles are the only AK-pattern assault rifles that use spike bayonets.

- Military issued versions of the Type 56 lack the threaded muzzle found on the AK-47 and AKM, this means they cannot use an AKM compensator or blank-firing device. Commercial versions of the Type 56 may or may not have a threaded muzzle.

- Has a blued finish like the AK-47 and unlike the AKM, which has a black oxide finish or a parkerized finish.

- Has "in the white" bolt carrier, while the AKM bolt carrier is blued.

- Like the AK-47, sights will only adjust to 800 metres, whereas AKM sights adjust to 1000 metres.

- Nearly all Type 56's lack the side mount plate that was featured on many variations of the AK-47 and AKM.

- Lacks the hammer release delay device of the AKM. The lack of hammer retarder is perhaps due to a preference of a slightly higher rate of fire, and simplicity. And did not have anything to do with thickness of the receiver, as the RPK included the hammer retarder also.

- The gas relief ports are located on the gas tube like the AK-47, unlike the AKM which had the gas relief ports relocated forward to the gas block.

- The fixed stock of a Type 56 has a less in-line stock like the AK-47, opposed to the AKM which has a straighter stock.

Variants

- Type 56 – Basic variant introduced in 1956. Copy of the AK-47 with a fixed wooden stock and permanently attached spike bayonet. In the mid-1960s production switched from machined to stamped receivers, mimicking the improved (and cheaper) Russian AKM, while the permanently attached bayonet became optional. Still used by Chinese reserve and militia units.

- Type 56-I – Copy of the AKS, with an under-folding steel shoulder stock and the bayonet removed to make the weapon easier to carry. As with the original Type 56, milled receivers were replaced by stamped receivers in the mid-1960s, making the Type 56-1 an equivalent to the Russian AKMS.

- Type 56-II – Improved variant and copy of AKM. Introduced in 1980, with a side-folding stock. Mainly manufactured for export and rare in China.

- Type 56-4 – Under folding stock copy of Type 56-1 in 5.56×45mm NATO. 1/12 barrel twist to stabilize the M193 NATO cartridge. Under folding spike bayonet. Chrome-plated bore and chamber. Selective fire. Barrel is extended past front sight 3 3⁄4 inches. Threaded flush muzzle cap. English fire control markings "S" and "F" for export version. No marking on the full-auto selection. Rear sight calibrated to 800 metres. Stamped receiver. Serial number marked on bolt carrier, bolt, receiver cover, receiver.

- Type 56C (QBZ-56C) – Short-barrel version, introduced in 1991 for the domestic and export market. The QBZ-56C as it is officially designated in China, is a carbine variant of the Type 56-II and supplied in limited quantities to some PLA units. The Chinese Navy is now the most prominent user. Development began in 1988, after it was discovered that the Type 81 assault rifle was too difficult to shorten. In order to further reduce weight the bayonet lug was removed. The QBZ-56C is often carried with a twenty-round box magazine, although it is capable of accepting a standard Type 56 thirty-round magazine.[10]

- Type 56S or Type 56 Sporter, also known as the MAK-90 (Model of the AK)-1990 – civilian version with only semiautomatic mode.[11]

- NHM 91 – Sporterized RPK-style version with a stamped receiver and 20" heavy barrel.

- Type 84S – A civilian version of the Type 56 rifle chambered for the 5.56×45mm NATO round.

- KL-7.62 – An unlicensed, reverse-engineered Iranian copy of the Type 56. The original version of the KL-7.62 was indistinguishable from the Type 56, but in recent years DIO appears to have made some improvements to the Type 56 design, adding a plastic stock and handguards (rather than wood) and a ribbed receiver cover (featured on most AKM variants, but missing from the Type 56) as well as picatinny rails on even newer versions.

- MAZ – Sudanese licensed copy of the Type 56 made by Military Industry Corporation.

Other Type 56 weapons

The "Type 56" designation was also used for Chinese versions of the SKS and of the RPD, known as the Type 56 carbine and Type 56 light machine gun respectively. However, unlike the popular Type 56 rifle, all Type 56 carbines have been removed from military service, except a few used for ceremonial purposes and by local Chinese militia. The Type 56 light machine gun is still used by the Cambodian Army and Sri Lankan Army.

AME-74-KA

The AME-74-KA appears to be an Iranian copy using locally manufactured parts. Manufactured of pressed mild steel and chambered for 7.62×39mm, it is a curious mix of design features. It has the gas block and sights of a Type 56, but the left-folding stock of an AK-102. The flash hider is of a more western design that appears to be inspired by the Heckler & Koch G36 open cage flash hider, but with large threading that suggests an intended muzzle attachment such as a grenade launcher or possibly a suppressor. No provision is made for a bayonet. Furniture is of a modern polymer material, but the foregrip is not equipped with heat shields internally, which would almost certainly cause issues in sustained fire. Magazines are identical to those used on a Type 56. Fit and finish is particularly bad, even for Iranian weapons, and it is thought that production was very limited due to scarcity. Examples have been recovered in Somalia, Iraq, and Yemen, all in poor condition. Markings on the right side of the weapon are conventional and in western characters. On the left side of the weapon appears AME-74-KA in both western and Farsi script, with no other markings. No manufacturer stamp appears anywhere on the weapon.

Users

Afghanistan[12]

Afghanistan[12] Albania - Uses the Type 56 and various copies of the AK-47/AKM, including domestic-built examples.[13]

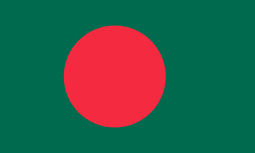

Albania - Uses the Type 56 and various copies of the AK-47/AKM, including domestic-built examples.[13] Bangladesh - Built under license by Bangladesh Ordnance Factories and used by the Bangladesh Navy, Special Warfare Diving And Salvage.[14]

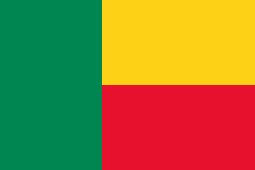

Bangladesh - Built under license by Bangladesh Ordnance Factories and used by the Bangladesh Navy, Special Warfare Diving And Salvage.[14] Benin[15]

Benin[15] Bolivia[16]

Bolivia[16] Burkina Faso[17]

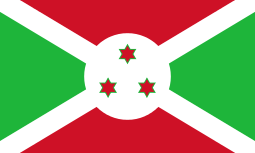

Burkina Faso[17] Burundi[18]

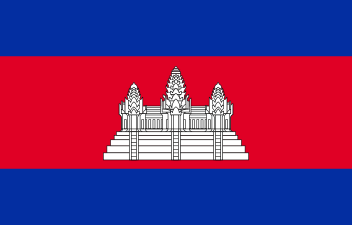

Burundi[18] Cambodia - Used extensively by the Khmer Rouge during the Cambodian Civil War. In service with the Royal Cambodian Armed Forces (the Type 56, Type 56-I, and Type 56-II).[19][20]

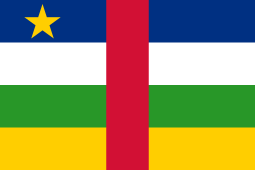

Cambodia - Used extensively by the Khmer Rouge during the Cambodian Civil War. In service with the Royal Cambodian Armed Forces (the Type 56, Type 56-I, and Type 56-II).[19][20] Central African Republic: Used by Central African Gendarmerie.[21]

Central African Republic: Used by Central African Gendarmerie.[21] China - The Chinese Type 56 was the standard issue assault rifle of the Chinese military from the late 1950s until the 1980s when it was replaced by the newer Type 81 assault rifle in front line units.Chinese reserve, militia, People's Armed Police units, Border Defense Troops, Customs Ministry security forces and Ministry of justice Bureau of Prison Administration guards are still issued the Type 56 rifle and Type 56 carbine SKS.[3]

China - The Chinese Type 56 was the standard issue assault rifle of the Chinese military from the late 1950s until the 1980s when it was replaced by the newer Type 81 assault rifle in front line units.Chinese reserve, militia, People's Armed Police units, Border Defense Troops, Customs Ministry security forces and Ministry of justice Bureau of Prison Administration guards are still issued the Type 56 rifle and Type 56 carbine SKS.[3] Congo-Brazzaville[22]

Congo-Brazzaville[22] Congo-Kinshasa[23]

Congo-Kinshasa[23] Estonia - Type 56-2 used by some units of the Estonia Land Forces.[24]

Estonia - Type 56-2 used by some units of the Estonia Land Forces.[24] East Timor - Type 56-2 used by units of Naval Component of the Timor Leste Defence Force.[25]

East Timor - Type 56-2 used by units of Naval Component of the Timor Leste Defence Force.[25] Finland - Type 56-2 known as 7.62 RK 56 TP used by Finnish reserves.[26]

Finland - Type 56-2 known as 7.62 RK 56 TP used by Finnish reserves.[26] Gambia: Used by Gambian Peacekeepers in Darfur.[27]

Gambia: Used by Gambian Peacekeepers in Darfur.[27] Iran - Imported during the 1980s.

Iran - Imported during the 1980s. Iraq [28][29]

Iraq [28][29]

Ivory Coast[31]

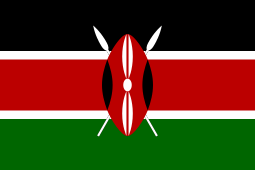

Ivory Coast[31] Kenya - Type 56-2 seen being used by Kenyan police responding to the 2013 Westgate shopping mall shooting[32][33]

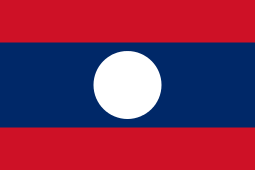

Kenya - Type 56-2 seen being used by Kenyan police responding to the 2013 Westgate shopping mall shooting[32][33] Laos[13]

Laos[13] Mali[13]

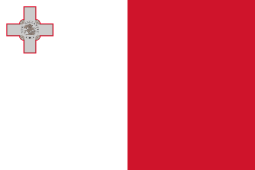

Mali[13] Malta[13]

Malta[13] Namibia[34]

Namibia[34] Niger[35]

Niger[35] Nigeria[36]

Nigeria[36] North Korea[13]

North Korea[13] Pakistan - Used by the Pakistan Army,[13] Pakistan Rangers, Frontier Corps & Police.

Pakistan - Used by the Pakistan Army,[13] Pakistan Rangers, Frontier Corps & Police.-

Rhodesia - Captured rifles were issued primarily to helicopter crews.[37]

Rhodesia - Captured rifles were issued primarily to helicopter crews.[37]  Rwanda - Imported through Zaire in defiance of trade sanctions, 1994.[38]

Rwanda - Imported through Zaire in defiance of trade sanctions, 1994.[38] Senegal[39]

Senegal[39] Sierra Leone[40]

Sierra Leone[40] Somalia[41]

Somalia[41]

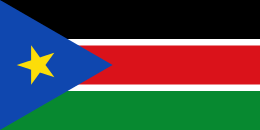

South Sudan - Seen being used by South Sudanese government soldiers during the 2013 South Sudanese coup d'état attempt[44]

South Sudan - Seen being used by South Sudanese government soldiers during the 2013 South Sudanese coup d'état attempt[44] Sri Lanka[13]

Sri Lanka[13] Syria

Syria Sudan - Produced under license.[45]

Sudan - Produced under license.[45] Tajikistan[46]

Tajikistan[46] Tanzania: Used by Tanzanian Peacekeepers in Darfur.[47]

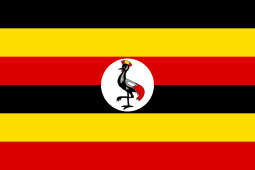

Tanzania: Used by Tanzanian Peacekeepers in Darfur.[47] Uganda[48]

Uganda[48] Vietnam - Used extensively by the NVA during the Vietnam War.[3]

Vietnam - Used extensively by the NVA during the Vietnam War.[3] Yemen[49]

Yemen[49] Zimbabwe - Used by Zimbabwe Presidential Guard[50]

Zimbabwe - Used by Zimbabwe Presidential Guard[50]

See also

References

- ↑ "NORINCO Type 56 (AK47) Assault Rifle / Assault Carbine".

- ↑ world.guns.ru on Type 56. Retrieved 29 April 2013.

- 1 2 3 Miller, David (2001). The Illustrated Directory of 20th Century Guns. Salamander Books Ltd. ISBN 1-84065-245-4.

- 1 2 Gordon Rottman (24 May 2011). The AK-47: Kalashnikov-series assault rifles. Osprey Publishing. pp. 47–49. ISBN 978-1-84908-835-0. Retrieved 16 July 2013.

- ↑ Bobi Pirseyedi (1 January 2000). The Small Arms Problem in Central Asia: Features and Implications. United Nations Publications UNIDIR. p. 16. ISBN 978-92-9045-134-1. Retrieved 16 July 2013.

- ↑ Warlow, Tom (2004). Firearms, the Law, and Forensic Ballistic (2nd ed.). CRC Press. pp. 26–27, 47. ISBN 9780203568224.

- ↑ King, Wayne (January 19, 1989). "Weapon Used by Deranged Man Is Easy to Buy". The New York Times. Retrieved 21 November 2014.

- ↑ Ingram, Carl (May 25, 1989). "Governor Signs Assault Weapon Legislation". Los Angeles Times. p. 1. Retrieved 21 November 2014.

- ↑ Smith, This story was reported by Times staff writers Doug. "Chilling Portrait of Robber Emerges" – via LA Times.

- ↑ "详解中国首款QBZ56C型短突击步枪(组图)" (in Chinese). Sina.com. 2007-08-28. Retrieved 2008-08-26.

- ↑ Norinco. Chicom47.net. Retrieved on 2012-05-20.

- ↑ 070317-A-LI455-010. Defenseimagery.mil. Retrieved on 2012-05-20.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Jones, Richard D. Jane's Infantry Weapons 2009/2010. Jane's Information Group; 35 edition (January 27, 2009). ISBN 978-0-7106-2869-5.

- ↑ "Bangladesh Military Forces - BDMilitary.com". Bangladesh Military Forces - BDMilitary.com. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- ↑ http://www.marines.mil/unit/marforaf/PublishingImages/090616-M-3107S-0461.jpg

- ↑ Bolivia Land Forces military equipment and vehicles Bolivian Army. Armyrecognition.com. Retrieved on 2012-05-20.

- ↑ Staff Sgt. Candace Mundt (2016-05-16). "Intel officer provides oversight for Western Accord 2016 camp security". US Army Africa. Retrieved 2017-06-20.

- ↑ Nzosaba Jean Bosco and Yvan Rukundo (2017-01-26). "Army major shot dead in eastern Burundi". Anadolu Agency. Retrieved 2017-06-25.

- ↑ Working Papers. Small Arms Survey (2011-12-01). Retrieved on 2012-05-20.

- ↑ Unwin, Charles C.; Vanessa U., Mike R., eds. (2002). 20th Century Military Uniforms (2nd ed.). Kent: Grange Books. ISBN 0760730946.

- ↑ UN Mission in the Central African Republic MINUSCA (2017-06-12). "BF6V3771". UNMINUSCA. Retrieved 2017-06-19.

- ↑ Abel Kavanagh (2010-07-15). "Congo forces armées congolaises 14 juillet 2010". MONUSCO Photos. Retrieved 2017-06-22.

- ↑ Army Recognition (2015-02-25). "Aveba, district de l’Ituri, Province Orientale, DR Congo : Des militaires FARDC en patrouille.". armyrecognition.com. Retrieved 2017-06-22.

- ↑ "56-2式冲锋枪(原版)详解 – 铁血网".

- ↑ "ForumDefesa.com". Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- ↑ "散布在世界各个角落里的中国轻兵器!(图片) – 铁血网".

- ↑ Albert Gonzalez Farran (2014-05-26). "Launch of the DIDC Committee". UNAMID. Retrieved 2017-06-04.

- ↑ "070606-F-7418E-005". Flickr - Photo Sharing!.

- ↑ https://fbcdn-sphotos-g-a.akamaihd.net/hphotos-ak-xpa1/v/t1.0-9/10245327_10152105933328568_8847179887157629928_n.jpg?oh=84a3eb47558415fc4698e41e17dce5eb&oe=5522ADAC&__gda__=1432114362_65baac937fdbc07aa7a3aabb6f8f2467 flickr.com/photos/familymwr

- ↑ Eduardo Gonzalez (2015-09-06). "Iraqi Kurdish Peshmerga: Divided from Within". Ekurd Daily. Retrieved 2017-06-22.

- ↑ Richelle Carey (2017-01-08). "Behind Ivory Coast's army mutiny". Al Jazeera News. Retrieved 2017-06-14.

- ↑ "Gunmen Kill Dozens in Terror Attack at Kenyan Mall". New York Times.com. 2013-09-21. Retrieved 2013-09-22.

- ↑ "Gunmen attack mall in Kenya". NBS News.com. Retrieved 2013-09-22.

- ↑ Elena Torreguitar. National Liberation Movements in Office: Forging Democracy with African Adjectives in Namibia (2009 ed.). Peter Lang GMBH. p. 159. ISBN 978-3-631-57995-4.

- ↑ THE ASSOCIATED PRESS (2015-04-27). "Boko Haram attacks Niger Army base". arab news. Retrieved 2017-06-14.

- ↑ Olisa TV (2017-02-22). "Nigerian Army confirms soldier missing after Lagos ambush". Premium Times. Retrieved 2017-06-14.

- ↑ Neil Grant (2015). Rhodesian Light Infantryman: 1961-1980. Osprey Publishing. pp. 21, 26. ISBN 1472809629.

- ↑ Rwanda

- ↑ Emanuelle Landais (2016-02-29). "IUS led Flintlock counter-terrorism exercises end in Senegal". dw.com. Retrieved 2017-06-15.

- ↑ U.S. Army Africa (2011-07-26). "Sierra Leone ACOTA, July 2011". US Army Africa. Retrieved 2017-06-28.

- ↑ Louis Charbonneau (2014-10-10). "Exclusive: Somalia army weapons sold on open market - U.N. monitors". Reuters. Retrieved 2017-06-22.

- ↑ (in Somali)Garoowe (2016-12-08). "Daawo Sawirada: Qaabka ay Ciidamada Puntland ula wareegen Qandala". Caasimada Online. Retrieved 2017-07-04.

- ↑ ansar (2013-05-26). "Somalia". World Military and Police Forces. Retrieved 2017-08-06.

- ↑ "S Sudan rebels 'control key state'". BBC News. 2013-12-21.

- ↑ "MAZ". Military Industry Corporation. Retrieved 2009-02-08.

- ↑ "DVIDS - Images - Tajik NCOs Learning New Responsibilities During U.S.-led Exchange [Image 8 of 10]". DVIDS. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- ↑ Albert Gonzalez Farran (2014-06-30). "UNAMID's protection of civilians". UNAMID. Retrieved 2017-06-04.

- ↑ Reuters (2013-05-27). "Ugandan army chief fired after leaked letter". Aljazeera. Retrieved 2017-06-05.

- ↑ Joseph Cox (2013-08-19). "Are American Drones Al Qaeda's Strongest Weapon in Yemen?". Vice. Retrieved 2017-06-22.

- ↑ World Armies (2008-04-25). "Zimbabwe Presidential Guard". flicker. Retrieved 2017-04-06.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Type 56. |

- Sino Defence

- Modern Firearms

- 56 at IMFDB – detailing this weapon's use in Western cinema