Twenty-second Amendment to the United States Constitution

| This article is part of a series on the |

| Constitution of the United States of America |

|---|

|

|

Preamble and Articles of the Constitution |

| Amendments to the Constitution |

|

|

| Unratified Amendments |

| History |

| Full text of the Constitution and Amendments |

|

The Twenty-second Amendment (Amendment XXII) of the United States Constitution sets a term limit for election and overall time of service to the office of President of the United States. Congress passed the amendment on March 21, 1947. Ratification by the requisite 36 of the then-48 states was completed on February 27, 1951.

Text

Section 1. No person shall be elected to the office of the President more than twice, and no person who has held the office of President, or acted as President, for more than two years of a term to which some other person was elected President shall be elected to the office of the President more than once. But this article shall not apply to any person holding the office of President when this article was proposed by the Congress, and shall not prevent any person who may be holding the office of President, or acting as President, during the term within which this article becomes operative from holding the office of President or acting as President during the remainder of such term.Section 2. This article shall be inoperative unless it shall have been ratified as an amendment to the Constitution by the legislatures of three-fourths of the several states within seven years from the date of its submission to the states by the Congress.

History

Although the Twenty-second Amendment was clearly a reaction to Franklin D. Roosevelt's service as President for an unprecedented four terms, the notion of presidential term limits has long-standing roots in American politics. The Constitutional Convention of 1787 considered the issue extensively, although it ultimately declined to restrict the amount of time a person could serve as president. But following George Washington's decision to retire after his second elected term, numerous public figures subsequently argued he had established a "two-term tradition" that served as a vital check against any one person, or the presidency as a whole, accumulating too much power.[1]

In his Farewell Address, written near the end of his second term, Washington both reveals he considered not standing for reelection in 1792,[Note 1] and that his decision not to seek a third term in 1796 was due to age, not intention to set precedent. Eleven years later, Thomas Jefferson further contributed to the convention of a voluntary two-term limit when he wrote in 1807, "if some termination to the services of the chief Magistrate be not fixed by the Constitution, or supplied by practice, his office, nominally four years, will in fact become for life."[2] Three of the next four presidents after Jefferson—James Madison, James Monroe, and Andrew Jackson—served two terms, and each one adhered to the two-term principle.

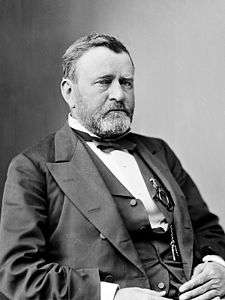

In spite of the strong two-term tradition, a few presidents prior to Franklin Roosevelt did attempt to secure a third term. Ulysses S. Grant, after having served as president from 1869 to 1877, sought nomination for another term at the 1880 Republican National Convention, but narrowly lost to James Garfield, who would go on to win the 1880 election. Given the Republican Party's dominance during that period, had Grant been nominated, he might well have won a third term.

Theodore Roosevelt succeeded to the presidency on September 14, 1901, following William McKinley's assassination (194 days into his second term), and was subsequently elected to a full term in 1904. While he declined to seek a third (second full) term in 1908, Roosevelt did seek one four years later, in the election of 1912, where he lost to Woodrow Wilson. Wilson himself sought nomination to a third term in 1920, at the Democratic National Convention;[3] he deliberately blocked the nomination of the former Secretary of the Treasury, his son-in-law William Gibbs McAdoo, the front-runner. Although seriously ill at the time, Wilson anticipated that the party would side with their sitting president were the convention deadlocked. Wilson was too unpopular even within his own party at the time, and James M. Cox was nominated. He would again contemplate running for a nonconsecutive third term in 1924, devising a strategy for his comeback, but again lacked any support and died at the beginning of the year.[4]

.jpg)

Franklin D. Roosevelt spent the months leading up to the 1940 Democratic National Convention refusing to state whether he would seek a third term. His Vice President, John Nance Garner, along with Postmaster General James Farley, announced their candidacies for the Democratic nomination. When the convention came, Roosevelt sent a message to the convention, saying he would run only if drafted, saying delegates were free to vote for whomever they pleased. The delegates issued 946 votes for Roosevelt, 72 for Farley, and 61 for Garner; they replaced Garner with Henry A. Wallace as the vice presidential nominee, and Farley resigned as postmaster general. In the 1940 general election, while Republican Wendell Willkie received six million more votes than the previous Republican candidate (Alfred Landon) had in 1936, Roosevelt still won decisively, taking 38 of 48 states. His supporters cited impending war as a reason for breaking with precedent, while Willkie had run against the principle of a third term. Roosevelt was the first president elected to a third term, and remains the only one to exceed eight years in office.

Four years later, in the election of 1944, Roosevelt defeated New York governor Thomas E. Dewey to win an unprecedented fourth term. While he effectively quelled rumors of his poor health during the campaign, Roosevelt's health was in reality deteriorating. On April 12, 1945, only 82 days after his fourth inauguration, he suffered a cerebral hemorrhage and died.

Near the end of the 1944 campaign, Thomas Dewey announced support of an amendment that would limit future presidents to two terms. According to Dewey, "four terms, or sixteen years (which is what Roosevelt would have served had he lived until 1949), is the most dangerous threat to our freedom ever proposed."[5] The Republican-controlled 80th Congress approved a Joint resolution "proposing an amendment to the Constitution relating to the terms of office of the president". in March 1947;[6] it was signed by Speaker of the House Joseph W. Martin and acting President pro tempore of the Senate William F. Knowland.[7] The ratification process for the 22nd Amendment was completed on February 27, 1951, 3 years, 343 days after it was sent to the states. The new amendment's 2-term limit did not apply (due to the grandfather clause in Section 1) to the incumbent president, Harry S. Truman. He remained eligible for election to more than two terms.[6]

On November 22, 1963, President John F. Kennedy was assassinated while riding through Dealey Plaza in downtown Dallas, Texas. Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson, who was also in the motorcade, three cars back, was unhurt. Shortly after Kennedy died, Johnson was sworn in as the nation's 36th president, and served out the remaining 1 year, 59 days of Kennedy's term. Under the terms of the 22nd Amendment, Johnson, who ran for and won a full four–year term in 1964 was eligible to run for another full term in 1968 (as he had served less than two years of Kennedy's term). He chose not to do so, announcing his intentions in a March 31, 1968, speech to the nation, saying, "I shall not seek, and I will not accept, the nomination of my party for another term as your president."[8] Had he done so and won, and served the full term (through January 20, 1973), the total length of his presidency would have been 9 years, 59 days.

Proposal and ratification

Congress proposed the Twenty-second Amendment on March 21, 1947.[9] The proposed amendment was adopted on February 27, 1951.

The following states ratified the amendment:

- Maine (March 31, 1947)

- Michigan (March 31, 1947)

- Iowa (April 1, 1947)

- Kansas (April 1, 1947)

- New Hampshire (April 1, 1947)

- Delaware (April 2, 1947)

- Illinois (April 3, 1947)

- Oregon (April 3, 1947)

- Colorado (April 12, 1947)

- California (April 15, 1947)

- New Jersey (April 15, 1947)

- Vermont (April 15, 1947)

- Ohio (April 16, 1947)

- Wisconsin (April 16, 1947)

- Pennsylvania (April 29, 1947)

- Connecticut (May 21, 1947)

- Missouri (May 22, 1947)

- Nebraska (May 23, 1947)

- Virginia (January 28, 1948)

- Mississippi (February 12, 1948)

- New York (March 9, 1948)

- South Dakota (January 21, 1949)

- North Dakota (February 25, 1949)

- Louisiana (May 17, 1950)

- Montana (January 25, 1951)

- Indiana (January 29, 1951)

- Idaho (January 30, 1951)

- New Mexico (February 12, 1951)

- Wyoming (February 12, 1951)

- Arkansas (February 15, 1951)

- Georgia (February 17, 1951)

- Tennessee (February 20, 1951)

- Texas (February 22, 1951)

- Nevada (February 26, 1951)

- Utah (February 26, 1951)

- Minnesota (February 27, 1951)

Ratification was completed on February 27, 1951. The amendment was subsequently ratified by the following states: - North Carolina (February 28, 1951)

- South Carolina (March 13, 1951)

- Maryland (March 14, 1951)

- Florida (April 16, 1951)

- Alabama (May 4, 1951)

In addition, the following states voted to reject the amendment:

- Oklahoma (June 1947)

- Massachusetts (June 9, 1949)

The following states took no action to consider the amendment:

- Arizona

- Kentucky

- Rhode Island

- Washington

- West Virginia

(Neither Alaska nor Hawaii had yet been admitted as states at the time.)

Attempts at repeal

According to historian Glenn W. LaFantasie of Western Kentucky University (who was opposed to repealing the amendment), "ever since 1985, when Ronald Reagan was serving in his second term as president, there have been repeated attempts to repeal the Twenty-second Amendment to the Constitution, which limits each president to two terms."[10] In early 1989, during an exit interview with Tom Brokaw of NBC, President Reagan stated his intention to fight for the amendment's repeal.[11] However, after being diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease in 1994, his post-presidential ambitions had to be scrapped.

In addition, several congressmen, including Democrats Rep. Barney Frank, Rep. José E. Serrano,[12] Rep. Howard Berman, and Sen. Harry Reid,[13] and Republicans Rep. Guy Vander Jagt,[14] Rep. David Dreier[15] and Sen. Mitch McConnell[16] have introduced legislation to repeal the Twenty-second Amendment, but each resolution died before making it out of its respective committee. Other alterations have been proposed, including replacing the absolute two term limit with a limit of no more than two consecutive terms and giving Congress the power to grant an exemption to a current or former president by way of a supermajority vote in both houses.

On January 4, 2013, Rep. José E. Serrano again introduced a resolution proposing an Amendment to repeal the Twenty-second Amendment, as he had done every two years since 1997; he did not do so during the 114th Congress.[17][18]

Interaction with the Twelfth Amendment

There is a point of contention regarding the interpretation of the Twenty-second Amendment as it relates to the Twelfth Amendment, ratified in 1804, which provides that "no person constitutionally ineligible to the office of President shall be eligible to that of Vice President of the United States".

While it is clear that under the Twelfth Amendment the original constitutional qualifications of age, citizenship, and residency apply to both the President and Vice President, it is unclear whether a two-term president could later serve as Vice President. Some argue that the Twenty-second Amendment and Twelfth Amendment bar any two-term president from later serving as Vice President as well as from succeeding to the presidency from any point in the United States presidential line of succession.[19] Others contend that the Twelfth Amendment concerns qualification for service, while the Twenty-second Amendment concerns qualifications for election, and thus a former two-term president is still eligible to serve as vice president.[20][21] The practical applicability of this distinction has not been tested, as no former president has ever sought the vice presidency, although in 1980, former president Gerald Ford was mentioned as a possible running mate for Republican presidential nominee Ronald Reagan and there were some negotiations between the two camps. Nothing ever became of the idea,[22] and had Ford been selected, it would not have violated the 22nd Amendment, as he had only served less than one full term in finishing out Richard Nixon's second term. During Hillary Clinton's 2016 candidacy, she jokingly said that she had considered naming Bill Clinton as her Vice President, but had been advised it would be unconstitutional.[23]

The Constitution does not restrict the number of terms a person can serve as Vice President.[24]

Affected individuals

The amendment explicitly did not apply to the sitting president (Harry S. Truman) at the time it was proposed by Congress. Truman, who had served nearly all of Franklin D. Roosevelt's unexpired fourth term and who had been elected to a full term in 1948, was thus eligible to seek re-election in 1952. However, after poor performance in the 1952 New Hampshire primary, Truman chose not to seek his party's nomination. He theoretically also would have been eligible in later elections.

Since the amendment's ratification, Dwight D. Eisenhower, Richard M. Nixon, Ronald Reagan, Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, and Barack Obama have been elected president twice. The same party has won the presidency in three consecutive elections only once since World War II, when Republican George H. W. Bush won in 1988 after two terms as Vice President with Republican Ronald Reagan. In all other cases, the opposing party's candidate has won after two terms with a single party: Dwight D. Eisenhower (R) in 1952, John F. Kennedy (D) in 1960, Richard Nixon (R) in 1968, Jimmy Carter (D) in 1976, George W. Bush (R) in 2000, Barack Obama (D) in 2008, and Donald Trump (R) in 2016. The only president who took office after the ratification of the Twenty-second Amendment and who could have served more than eight years was Lyndon B. Johnson.[25][26] He became President in 1963 when John F. Kennedy was assassinated, served the final 14 months (less than two years) of Kennedy's term, was elected president in 1964, and ran briefly for re-election in 1968 but chose to withdraw from the race. Gerald Ford became president on August 9, 1974, and served the final 29 months (more than two years) of Richard Nixon's unexpired term. Ford, who lost to Jimmy Carter in 1976, would have been eligible to be elected in his own right only once. As of 2017, the only former presidents who remain technically eligible to seek another term are Jimmy Carter and George H. W. Bush, who each served a single term decades ago; both are now in their 90s and neither has announced any plans to run again.

Notes

- ↑ See George Washington's Farewell Address, ¶ 3. Washington considered, but quickly chose to seek reelection on basis of international crises and the advice of his counsel.

References

- Constitution of the United States.

- Peabody, Bruce G.; Gant, Scott E. (February 1999). "The Twice and Future President: Constitutional Interstices and the Twenty-Second Amendment". Minnesota Law Review. 83 (3): 565–635. Archived from the original on January 15, 2013. Retrieved June 12, 2015.

- ↑ Peabody, Bruce. "Presidential Term Limit". The Heritage Foundation. Retrieved January 10, 2017.

- ↑ Thomas Jefferson: Reply to the Legislature of Vermont, 1807. ME 16:293

- ↑ Pietrusza, David (2007). The Year of the Six Presidents. New York: Carroll and Graf.

- ↑ Saunders, Robert M. (1998). In Search of Woodrow Wilson: Beliefs and Behavior. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 9780313305207.

- ↑ David M. Jordan, FDR, Dewey, and the Election of 1944 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2011, p. 290) ISBN 978-0-253-35683-3

- 1 2 "FDR’s third-term decision and the 22nd amendment". National Constitution Center. Retrieved June 29, 2014.

- ↑ "22nd Amendment". Stanley L. Klos. Retrieved June 30, 2014.

- ↑ "The 1968 Exhibit: LBJ's "I shall not seek, and I will not accept" televised speech, March 31, 1968". 1968 Blog. Minnesota Historical Society. Retrieved January 19, 2017.

- ↑ Mount, Steve (January 2007). "Ratification of Constitutional Amendments". Retrieved May 9, 2012.

- ↑ LaFantasie, Glenn (March 20, 2011) The erosion of the Civil War consensus, Salon

- ↑ "President Reagan Says He Will Fight to Repeal 22nd Amendment". archives.nbclearn.com. Retrieved June 14, 2015.

- ↑ H.J.Res. 5.Introduced January 6, 2009.

- ↑ S.J.Res. 36. Sponsored by Harry Reid. January 31, 1989.

- ↑ H.J.Res. 61

- ↑ H.J.Res. 51

- ↑ S.J.Res. 23

- ↑ "Proposing an amendment to the Constitution of the United States to repeal the twenty-second article of amendment, thereby removing the limitation on the number of terms an individual may serve as President. (2013; 113th Congress H.J.Res. 15) - GovTrack.us". GovTrack.us.

- ↑ "Jose E. Serrano | Congress.gov | Library of Congress". www.congress.gov. Retrieved June 14, 2015.

- ↑ Matthew J. Franck (July 31, 2007). "Constitutional Sleight of Hand". National Review. Archived from the original on June 13, 2008. Retrieved June 12, 2008.

- ↑ Michael C. Dorf (August 2, 2000). "Why the Constitution permits a Gore-Clinton ticket". CNN Interactive. Archived from the original on October 1, 2005.

- ↑ Scott E. Gant; Bruce G. Peabody (June 13, 2006). "How to bring back Bill". The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved June 12, 2008.

- ↑ Burr, Richard (April 7, 2017). "1980 convention launched 'Reagan Revolution'". The Detroit News. Retrieved May 26, 2017.

- ↑ 1339 GMT (2039 HKT) September 15, 2015 (September 15, 2015). "Hillary Clinton: Bill as VP has 'crossed her mind' - CNNPolitics.com". Edition.cnn.com. Retrieved October 29, 2015.

- ↑ "Who were FDR's Vice Presidents?". Docs.fdrlibrary.marist.edu. Retrieved October 29, 2015.

- ↑ "Johnson Can Seek Two Full Terms". The Washington Post. November 24, 1963. p. A2.

- ↑ Moore, William (November 24, 1963). "Law Permits 2 Full Terms for Johnson". The Chicago Tribune. p. 7.

External links

- National Archives: AMENDMENT XXII

- H.J.RES.5—The latest bill introduced in Congress proposing to repeal the Twenty-second Amendment. There have been many similar proposals introduced in previous Congresses, none of which has been acted on. This proposal remains in committee.

- CRS Annotated Constitution: Twenty-second Amendment