Twa

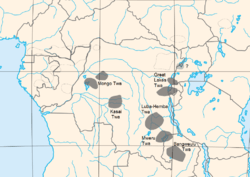

.png) Twa populations according to Hewlett & Fancher. From west to east: Ntomba, Kasai, [unidentified], Great Lakes, Nsua [not clear if Nsua is Twa]. .png) Twa populations according to Stokes. Only a few groups are shown, but these include several between the Kasai and Great Lakes Twa.  Twa/pygmoid populations according to Cavalli-Sforza. Several southern groups are added. _small.png) Twa populations scattered through shaded area, according to Blench. Several southern Twa areas are shown. | |

| Languages | |

|---|---|

| Bantu, French | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Pygmies |

| Twa | |

|---|---|

| Person | Mutwa |

| People | Batwa |

| Language | (NA) |

| Country | Butwa |

The Twa (also Cwa[1]) are any of several African hunting peoples or castes who live interdependently with agricultural Bantu populations, and who generally hold a socially subordinate position: They provide the farming population with game in exchange for agricultural products.

Name

Abatwa/Abathwa/Batwa is a derivative root word common to the Bantu language group. It is often supposed that the Pygmies were the aboriginal inhabitants of the forest before the advent of agriculture. Vansina argues that the original meaning of the (Proto-Bantu) word *Twa was "hunter-gatherer, bushpeople", and that this became conflated with another root for Twa/Pygmy, *Yaka (as in Ba-Yaka).[2] As the Twa caste developed into full-time hunter-gatherers, the words were conflated, and the ritual role of the absorbed aboriginal peoples was transferred to the Twa.[3][4]

Relation to the Bantu populations

There is no Pygmy or Twa population that live independently of agriculture; all live near or in agricultural villages. Agricultural Bantu peoples have settled a number of ecotones next to an area that has game but will not support agriculture, such as the edges of the rainforest, open swamp, and desert, and the Twa spend part of the year in the otherwise uninhabited region hunting game, being provided with agricultural food by the farmers while they do so.

Roger Blench has proposed that Twa (Pygmies) originated as a caste like they are today, much like the Numu blacksmith castes of West Africa, economically specialized groups which became endogamous and consequently developed into separate ethnic groups, sometimes, as with the Ligbi, with their own languages. A mismatch in language between patron and client could later occur from population displacements. The short stature of the "forest people" could have developed in the few millennia since the Bantu expansion, as also happened with Bantu domestic animals in the rainforest, especially if there was additional selective pressure from farmers taking the tallest women back to the village as wives. However, that is incidental to the social identity of the Pygmy/Twa.[4]

Congo

Twa live scattered throughout the Congo. In addition to the Great Lakes Twa of the dense forests under the Ruwenzoris, there are notable populations in the swamp forest around Lake Tumba in the west (about 14,000 Twa, more than the Great Lakes Twa in all countries), in the forest–savanna swamps of Kasai in the south-center, and in the savanna swamps scattered throughout Katanga in the south-east, as in the Upemba Depression with its floating islands, and around Kiambi on the Luvua River.

Arab and colonial accounts speak of Twa on either side of the Lomami River southwest of Kisangani, and on the Tshuapa River and its tributary the "Bussera".

Among the Mongo, on the rare occasions of caste mixing, the child is raised as Twa. If this is a common pattern with Twa groups, it may explain why the Twa are less physically distinct from their patrons than the Mbenga and Mbuti, where village men take Pygmy women out of the forest as wives.[5]

The Congolese variant of the name, at least in Mongo, Kasai, and Katanga, is Cwa.[1]

Uganda

The Batwa of Uganda were forest dwellers who lived by gathering and hunting as the main source of food. They are believed to have lived in the Bwindi Impenetrable and Mgahinga National parks that border Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and Rwanda living mainly in areas bordering other Bantu Tribes.

In 1992, the lives of the Batwa pygmies changed forever. The Bwindi Impenetrable Forest became a national park and World Heritage Site to protect the 350 endangered mountain gorillas within its boundaries. The Batwa were evicted from the park. Since they had no title to land, they were given no compensation. The Batwa became conservation refugees in an unfamiliar, unforested world. Poverty, drug and alcohol abuse, lack of education facilities, HIV as well as gender-based violence and discrimination are higher among Batwa communities than among the neighboring, Bantu communities.[6]

Angola and Namibia

Southern Angola through central Namibia had Twa populations when Europeans first arrived in the 16th century. Estermann writes,

The southern Twa today live in close economic symbiosis with the tribes among which they are scattered—Ngambwe, Havakona, Zimba and Himba. None of the individuals I have observed differs physically from the neighboring Bantu.[7]

These peoples live in desert environments. Accounts are limited and tend to confuse the Twa with the San.[4]

Zambia and Botswana

The Twa of these countries live is swampy areas, such as the Twa fishermen of the Bangweulu Swamps, Lukanga Swamp, and Kafue Flats of Zambia; only the Twa fish in Southern Province, where the swampy terrain means that large-scale crops cannot be planted near the best fishing grounds.[8]

Cavalli-Sforza also shows Twa near Lake Mweru on the Zambia–Congo border. There are two obvious possibilities: the Luapula Swamps, and the swamps of Lake Mweru Wantipa. The latter is Taabwa territory, and the Twa are reported to live among the Taabwa.[9] The former is reported to be the territory of Bemba-speaking Twa.[10]

See also

References

- 1 2 A local variant of Twa in Congo. Pronounced {IPA-xx|tʃwa|}.

- ↑ Vansina, Jan. 1990. Paths in the Rainforests: Toward a history of political tradition in equatorial Africa.

- ↑ Scattered small hunter-gatherer populations survive in out-of-the-way places, some, such as the Hadza, with their original languages intact.

- 1 2 3 Blench, Roger. 1999. "Are the African Pygmies an Ethnographic Fiction?". Pp 41–60 in Biesbrouck, Elders, & Rossel (eds.) Challenging Elusiveness: Central African Hunter-Gatherers in a Multidisciplinary Perspective. Leiden.

- ↑ Jean Hiernaux, 1977. "Adaptation of the African to the rain forest", in Harrison (ed.) Population Structure and Human Variation

- ↑ Vice news, Forced Out of the Forest: The Lost Tribe of Uganda, https://www.youtube.com/watch?t=824&v=ITzWIBHEPqA

- ↑ Estermann, Carlos. 1976. [Gibson, ed. and trans.] The ethnography of southwestern Angola, vol. I. Africana Publishing Company.

- ↑ Lehmann, D. 1977. "The Twa: People of the Kafue Flats". In Williams & Howard (eds.) Development and Ecology in the Lower Kafue Basin in the Nineteen Seventies, 41–46. University of Zambia.

- ↑ Ntole Kazadi, 1981. "Méprisés et admirés: l'ambivalence des relations entre le Bacwa (Pygmées) et les Bahemba (Bantu)." Africa 51-4.

- ↑ John Desmond Clark. 1970. The stone age cultures of Northern Rhodesia

- Francis, Michael(2009) ‘Silencing the past: Historical and archaeological colonisation of the Southern San [Abatwa] KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa’. Anthropology Southern Africa Vol 32 (3 & 4).

- Francis, Michael (2009) ‘Abatwa–The Eland Ceremony’ in Encyclopaedia of Social Movement Media. Sage Publications.

- Francis, Michael (2007) PhD Thesis University of KwaZulu-Natal: ‘Explorations in ethnicity and social change among San descendents of the Drakensberg Mountains, KwaZulu-Natal’.