Old River Control Structure

The Old River Control Structure (ORCS) is a floodgate system in a branch of the Mississippi River in central Louisiana. It regulates the flow of water leaving the Mississippi into the Atchafalaya River, thereby preventing the Mississippi river from changing course. Completed in 1963, the complex was built by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in a side channel of the Mississippi known as "Old River," between the Mississippi's current channel and the Atchafalaya Basin, a former channel of the Mississippi.[1][2][3][4][5] The Old River Control Structure is actually a complex containing the original low-sill and overbank structures, as well as the auxiliary structure that was constructed after the low-sill structure was damaged during the Mississippi River Flood of 1973. The complex also contains a navigation lock and the Sidney A. Murray, Jr. Hydroelectric Station.[6]

Old River

Before the 15th century, the Red River and Mississippi River were entirely separate and more or less parallel to one another.[3] Beginning in the 15th century, the Mississippi River created a small westward loop, later called Turnbull's Bend, near present-day Angola, Louisiana. This loop eventually intersected the Red River, making the downstream part of the Red River a distributary of the Mississippi; this distributary came to be called the Atchafalaya River.[3]

In the heyday of steamboats along the Mississippi River, it would take a boat several hours to travel the 20 miles of Turnbull's Bend, after which it would have progressed only a mile or so from the entrance to the bend. To reduce travel time, Captain Henry M. Shreve, a river engineer and namesake of Shreveport, Louisiana, dug a canal in 1831 through the neck of Turnbull's Bend; this canal became known as Shreve's Cut. At the next high water, the Mississippi roared through this channel.[7] The upper portion of Turnbull's Bend became the smaller Upper Old River while the lower portion became the larger Lower Old River. At first, the Lower Old River would flow eastward, to the Mississippi, until 1839, when locals began removing a log jam that was obstructing the Atchafalaya River. The project was finished in 1840. After that, the Lower Old River would flow eastward to the Mississippi when the Red River was high and the Mississippi was low, and westward to the Atchafalaya when the Mississippi was high and the Red River was low. Over time, the number of days when the river flowed east to the Mississippi decreased and the number of days when the river flowed west increased, until eventually the Lower Old River flowed west over half the time. By 1880, it rarely flowed eastward and was now rapidly capturing more and more of the flow of the Mississippi. With this extra intake of water, the channel of the Atchafalaya River was worn deeper and wider throughout the 1800s and early 1900s.[7] Between 1850 and 1950, the flow increased from <10% of the Mississippi to 30%, and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers began work on the Old River Control Structure (ORCS) to prevent the Atchafalaya becoming the main channel of the Mississippi. In 1963, the The ORCS was completed, and it completely sealed off the Old river. However, a lock, a diversion channel, and flood spillway were installed to allow barges to pass between the Atchafalaya and Mississippi.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers measured the amount of water flowing through the Mississippi River and compared it to the amount entering the Atchafalaya Basin by monitoring "latitude flow" at the latitude of the Red River Landing, located five miles downstream of Old River. In this case, latitude flow is a combination of the flows of the Mississippi and Atchafalaya rivers as they cross an imaginary line at that latitude.[3]

Between 1850 and 1950, the percentage of latitude flow entering the Atchafalaya River had increased from less than 10 percent to about 30 percent. By 1953, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers concluded that the Mississippi River could change its course to the Atchafalaya River by 1990 if it were not controlled, since this alternative path to the Gulf of Mexico through the Atchafalaya River is much shorter and steeper.[3]

The Corps completed construction on the Old River Control Structure in 1964 to prevent the main channel flow of the Mississippi River from altering its current course to the Gulf of Mexico through the natural geologic process of avulsion.[3][8] Historically, this natural process has occurred about every 1,000 years, and is overdue. Some researchers believe the likelihood of this event increases each year, despite artificial control efforts.[9]

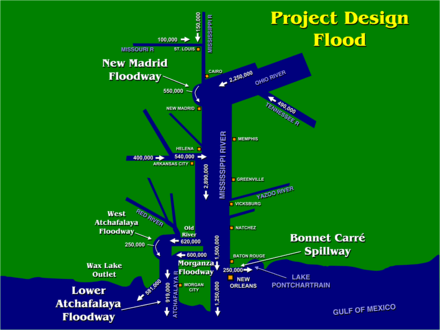

If the Mississippi diverts its main channel to the Atchafalaya Basin and the Atchafalaya River, it would develop a new delta south of Morgan City in southern Louisiana, greatly reducing water flow to its present channel through Baton Rouge and New Orleans.[4] The Mississippi Flood of 1973 almost caused the control structure to fail. Integrity of the Old River Control Structure, the nearby Morganza Spillway, and other levees in the area is essential to prevent such a diversion. Jeff Masters of Weather Underground noted that failure of that complex "would be a serious blow to the U.S. economy."[10]

Components

The present Old River Control Structure was completed in 1964 and expanded in 1990. The first two floodgates are the Low Sill Control Structure, which regulates routine flow in the waterway, and the Overbank Control Structure, in use only when the Mississippi exceeds its banks. A navigation channel and lock were also part of the original facility design. Subsequent expansion created what is now known as the Old River Control Complex, when the Auxiliary Structure, which became operational in 1986, was added to reduce pressure on the original floodgates after extensive damage caused by the flood of 1973. The Sidney A. Murray, Jr. Hydroelectric Station, completed in 1990, also provides an additional measure of control at the site.[3]

Operation

Water from the Mississippi is normally diverted into the Atchafalaya Basin only at Old River, where floodgates are routinely used to redirect the Mississippi's flow into the Atchafalaya River such that the volume of the two rivers is split 70%/30%, respectively, as measured at the latitude of Red River Landing.[11][12] This flow split was not based on science, but rather was based on the approximate flow allocation between the two rivers that existed at the time of construction.[6]

Water diverted at Old River flows into the Atchafalaya Basin, first entering the Red River, then continuing down the Atchafalaya River to the Gulf of Mexico, bypassing Baton Rouge and New Orleans (see diagram).

The Morganza Floodway, between the Mississippi and the Atchafalaya Basin nearby downstream, is normally closed, but can be opened in an emergency to relieve water levels and water-pressure stress on various levees and other flood-control structures, including the Old River Control Structure. The floodway can reduce stress by diverting additional water from the Mississippi into the Atchafalaya.[13] The Morganza Floodway was never used before the construction of ORCS, and has only been opened twice (as of 2016)[14] for flood control since completion of the ORCS.

See also

References

- ↑ McPhee, John (February 23, 1987). "The Control of Nature: Atchafalaya". The New Yorker. Retrieved May 12, 2011. Republished in McPhee, John (1989). The Control of Nature. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 0-374-12890-1.

- ↑ Angert, Joe and Isaac. "Old River Control". The Mighty Mississippi River. Archived from the original on May 15, 2009. Retrieved 2011-05-12.. Includes map and pictures.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Louisiana Old River Control Structure and Mississippi river flood protection". America's Wetland Resource Center. Loyola University's Center for Environmental Communication.

- 1 2 "Will the Mississippi River change its course in 2011 to the red line?". Mappingsupport. Retrieved May 8, 2011.

- ↑ Kemp, Katherine (January 6, 2000). "The Mississippi Levee System and the Old River Control Structure".

- 1 2 Piazza, Bryan P. (2014). The Atchafalaya River Basin: History and Ecology of an American Wetland. Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 978-1-62349-039-3.

- 1 2 "Simmesport, La.". The New York Times. Associated Press. May 3, 1987.

- ↑ "Mississippi Rising: Apocalypse Now?". Daily Impact. April 28, 2011. Retrieved May 10, 2011.

- ↑ Daniels, Ronald Joel (2006). On Risk and Disaster: Lessons from Hurricane Katrina. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 45.

- ↑ Masters, Jeff (May 9, 2011). "Mississippi River sets all-time flood records; 2nd major spillway opens". Weather Underground.

- ↑ "Mississippi River at Red River Landing (01120)". United States Army Corps of Engineers. May 7, 2011. Retrieved May 10, 2011.

- ↑ "Daily State and Discharge Data - Water Control - New Orleans District". U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Retrieved May 10, 2011.

- ↑ Rioux, Paul (May 14, 2011). "Morganza Floodway opens to divert Mississippi River away from Baton Rouge, New Orleans". NOLA.com.

- ↑ http://www.nola.com/weather/index.ssf/2016/01/morganza_floodway_will_not_be.html

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Old River Control Structure. |

- Weeks, John. "Old River Control Structure". Retrieved 2014-09-20.

Coordinates: 31°04′36″N 91°35′52″W / 31.0768°N 91.5979°W