Turbojet

| Part of a series on |

| Aircraft propulsion |

|---|

|

Shaft engines: driving propellers, rotors, ducted fans or propfans |

| Reaction engines |

| Others |

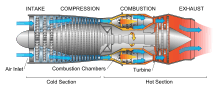

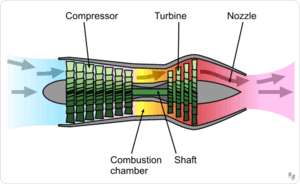

The turbojet is an airbreathing jet engine, usually used in aircraft. It consists of a gas turbine with a propelling nozzle. The gas turbine has an air inlet, a compressor, a combustion chamber, and a turbine (that drives the compressor). The compressed air from the compressor is heated by the fuel in the combustion chamber and then allowed to expand through the turbine. The turbine exhaust is then expanded in the propelling nozzle where it is accelerated to high speed to provide thrust.[1] Two engineers, Frank Whittle in the United Kingdom and Hans von Ohain in Germany, developed the concept independently into practical engines during the late 1930s.

Turbojets have been replaced in slower aircraft by turboprops because they have better range-specific fuel consumption. At medium speeds, where the propeller is no longer efficient, turboprops have been replaced by turbofans. The turbofan is quieter and has better range-specific fuel consumption than the turbojet. Turbojets are still common in medium range cruise missiles, due to their high exhaust speed, small frontal area, and relative simplicity.

Turbojets have poor efficiency at low vehicle speeds, which limits their usefulness in vehicles other than aircraft. Turbojet engines have been used in isolated cases to power vehicles other than aircraft, typically for attempts on land speed records. Where vehicles are 'turbine powered' this is more commonly by use of a turboshaft engine, a development of the gas turbine engine where an additional turbine is used to drive a rotating output shaft. These are common in helicopters and hovercraft.

History

The first patent for using a gas turbine to power an aircraft was filed in 1921 by Frenchman Maxime Guillaume.[2] His engine was to be an axial-flow turbojet, but was never constructed, as it would have required considerable advances over the state of the art in compressors.

In 1928, RAF College Cranwell cadet[3] Frank Whittle formally submitted his ideas for a turbojet to his superiors. In October 1929 he developed his ideas further.[4] On 16 January 1930 in England, Whittle submitted his first patent (granted in 1932).[5] The patent showed a two-stage axial compressor feeding a single-sided centrifugal compressor. Practical axial compressors were made possible by ideas from A.A.Griffith in a seminal paper in 1926 ("An Aerodynamic Theory of Turbine Design"). Whittle would later concentrate on the simpler centrifugal compressor only, for a variety of practical reasons. Whittle had the first turbojet to run, the Power Jets WU on 12 April 1937. It was liquid-fuelled, and included a self-contained fuel pump. Whittle's team experienced near-panic when the engine would not stop, accelerating even after the fuel was switched off. It turned out that fuel had leaked into the engine and accumulated in pools, so the engine would not stop until all the leaked fuel had burned off. Whittle was unable to interest the government in his invention, and development continued at a slow pace.

In Germany, Hans von Ohain patented a similar engine in 1935.[6]

On 27 August 1939 the Heinkel He 178 became the world's first aircraft to fly under turbojet power with test pilot Erich Warsitz at the controls,[7] thus becoming the first practical jet plane. The Gloster E.28/39, (also referred to as the "Gloster Whittle", "Gloster Pioneer", or "Gloster G.40") was the first British jet-engined aircraft to fly. It was designed to test the Whittle jet engine in flight, leading to the development of the Gloster Meteor.

The first two operational turbojet aircraft, the Messerschmitt Me 262 and then the Gloster Meteor entered service in 1944 towards the end of World War II.

Air is drawn into the rotating compressor via the intake and is compressed to a higher pressure before entering the combustion chamber. Fuel is mixed with the compressed air and burns in the combustor. The combustion products leave the combustor and expand through the turbine where power is extracted to drive the compressor. The turbine exit gases still contain considerable energy that is converted in the propelling nozzle to a high speed jet.

The first jet engines were turbojets, with either a centrifugal compressor (as in the Heinkel HeS 3), or Axial compressors (as in the Junkers Jumo 004) which gave a smaller diameter, although longer, engine. By replacing the propeller used on piston engines with a high speed jet of exhaust higher aircraft speeds were attainable.

One of the last applications for a turbojet engine was the Concorde which used the Olympus 593 engine. At the time of its design the turbojet was still seen as the optimum for cruising at twice the speed of sound despite the advantage of turbofans for lower speeds. For the Concorde less fuel was required to produce a given thrust for a mile at Mach 2.0 than a modern high-bypass turbofan such as General Electric CF6 at its Mach 0.86 optimum speed.

Turbojet engines had a significant impact on commercial aviation. Aside from giving faster flight speeds turbojets had greater reliability than piston engines, with some models demonstrating dispatch reliability rating in excess of 99.9%. Pre-jet commercial aircraft were designed with as many as 4 engines in part because of concerns over in-flight failures. Overseas flight paths were plotted to keep planes within an hour of a landing field, lengthening flights. The increase in reliability that came with the turbojet enabled three and two-engine designs, and more direct long-distance flights.[8]

High-temperature alloys were a reverse salient, a key technology that dragged progress on jet engines. Non-UK jet engines built in the 1930s and 1940s had to be overhauled every 10 or 20 hours due to creep failure and other types of damage to blades. British engines however utilised Nimonic alloys which allowed extended use without overhaul, engines such as the Rolls-Royce Welland and Rolls-Royce Derwent,[9] and by 1949 the de Havilland Goblin, being type tested for 500 hours without maintenance.[10] It was not until the 1950s that superalloy technology allowed other countries to produce economically practical engines.[11]

Early designs

Early German turbojets had severe limitations on the amount of running they could do due to the lack of suitable high temperature materials for the turbines. British engines such as the Rolls-Royce Welland used better materials giving improved durability. The Welland was type-certified for 80 hours initially, later extended to 150 hours between overhauls, as a result of an extended 500-hour run being achieved in tests.[12] A few of the original fighters still exist with their original engines, but many have been re-engined with more modern engines with greater fuel efficiency and a longer time between overhaul (such as the reproduction Me-262 powered by General Electric J85s).

General Electric in the United States was in a good position to enter the jet engine business due to its experience with the high-temperature materials used in their turbosuperchargers during World War II.[13]

Water injection was a common method used to increase thrust, usually during takeoff, in early turbojets that were thrust-limited by their allowable turbine entry temperature. The water increased thrust at the temperature limit, but prevented complete combustion, often leaving a very visible smoke trail.

Allowable turbine entry temperatures have increased steadily over time both with the introduction of superior alloys and coatings, and with the introduction and progressive effectiveness of blade cooling designs. On early engines, the turbine temperature limit had to be monitored, and avoided, by the pilot, typically during starting and at maximum thrust settings. Automatic temperature limiting was introduced to reduce pilot workload and reduce the liklehood of turbine damage due to overtemperature.

Design

Air intake

An intake, or tube, is needed in front of the compressor to help direct the incoming air smoothly into the moving compressor blades. Older engines had stationary vanes in front of the moving blades. These vanes also helped to direct the air onto the blades. The air flowing into a turbojet engine is always subsonic, regardless of the speed of the aircraft itself.

The intake has to supply air to the engine with an acceptably small variation in pressure (known as distortion) and having lost as little energy as possible on the way (known as pressure recovery). The ram pressure rise in the intake is the inlets contribution to the propulsion system overall pressure ratio and thermal efficiency.

The intake gains prominence at high speeds when it transmits more thrust to the airfame than the engine does. Well-known examples are the Concorde and Lockheed SR-71 Blackbird propulsion systems where the intake and engine contributions to the total powerplant were 63%/8%[14] at Mach 2 and 54%/17%[15] at Mach 3+.

Intakes have ranged from 'zero-length'[16] on the Pratt & Whitney TF33 installation in the Lockheed C-141 Starlifter to the twin, 65 feet-long, intakes on the North American XB-70 Valkyrie each feeding three engines with an intake airflow of about 800 lb/sec.

Compressor

The compressor is driven by the turbine. It rotates at high speed, adding energy to the airflow and at the same time squeezing (compressing) it into a smaller space. Compressing the air increases its pressure and temperature. The smaller the compressor, the faster it turns. At the large end of the range, the GE-90-115 fan rotates at about 2,500 RPM, while a small helicopter engine compressor rotates around 50,000 RPM.

Turbojets supply bleed air from the compressor to the aircraft for the environmental control system, anti-icing, and fuel tank pressurization, for example. The engine itself needs air at various pressures and flow rates to keep it running. This air comes from the compressor, and without it, the turbines would overheat, the lubricating oil would leak from the bearing cavities, the rotor thrust bearings would skid or be overloaded, and ice would form on the nose cone. The air from the compressor, called secondary air, is used for turbine cooling, bearing cavity sealing, anti-icing, and ensuring that the rotor axial load on its thrust bearing will not wear it out prematurely. Supplying bleed air to the aircraft decreases the efficiency of the engine because it has been compressed, but then does not contribute to producing thrust. Bleed air for aircraft services is no longer needed on the turbofan-powered Boeing 787.

Compressor types used in turbojets were typically axial or centrifugal. Early turbojet compressors had low pressure ratios up to about 5:1. Aerodynamic improvements including splitting the compressor into two separately rotating parts, incorporating variable blade angles for entry guide vanes and stators, and bleeding air from the compressor enabled later turbojets to have overall pressure ratios of 15:1 or more. For comparison, modern civil turbofan engines have overall pressure ratios of 44:1 or more. After leaving the compressor, the air enters the combustion chamber.

Combustion chamber

The burning process in the combustor is significantly different from that in a piston engine. In a piston engine, the burning gases are confined to a small volume, and as the fuel burns, the pressure increases. In a turbojet, the air and fuel mixture burn in the combustor and pass through to the turbine in a continuous flowing process with no pressure build-up. Instead, a small pressure loss occurs in the combustor.

The fuel-air mixture can only burn in slow-moving air, so an area of reverse flow is maintained by the fuel nozzles for the approximately stoichiometric burning in the primary zone. Further compressor air is introduced which completes the combustion process and reduces the temperature of the combustion products to a level which the turbine can accept. Less than 25% of the air is typically used for combustion, as an overall lean mixture is required to keep within the turbine temperature limits.

Turbine

Hot gases leaving the combustor expand through the turbine. Typical materials for turbines include inconel and Nimonic.[17] The hottest turbine vanes and blades in an engine have internal cooling passages. Air from the compressor is passed through these to keep the metal temperature within limits. The remaining stages do not need cooling.

In the first stage, the turbine is largely an impulse turbine (similar to a pelton wheel) and rotates because of the impact of the hot gas stream. Later stages are convergent ducts that accelerate the gas. Energy is transferred into the shaft through momentum exchange in the opposite way to energy transfer in the compressor. The power developed by the turbine drives the compressor and accessories, like fuel, oil, and hydraulic pumps that are driven by the accessory gearbox.

Nozzle

After the turbine, the gases expand through the exhaust nozzle producing a high velocity jet. In a convergent nozzle, the ducting narrows progressively to a throat. The nozzle pressure ratio on a turbojet is high enough at higher thrust settings to cause the nozzle to choke.

If, however, a convergent-divergent de Laval nozzle is fitted, the divergent (increasing flow area) section allows the gases to reach supersonic velocity within the divergent section. Additional thrust is generated by the higher resulting exhaust velocity.

Thrust augmentation

Thrust was most commonly increased in turbojets with water/methanol injection or afterburning. Some engines used both at the same time.

Liquid injection was tested on the Power Jets W.1 in 1941 initially using ammonia before changing to water and then water/methanol. A system to trial the technique in the Gloster E.28/39 was devised but never fitted.[18]

Afterburner

An afterburner or "reheat jetpipe" is a combustion chamber added to reheat the turbine exhaust gases. The fuel consumption is very high, typically four times that of the main engine. Afterburners are used almost exclusively on supersonic aircraft, most being military aircraft. Two supersonic airliners, Concorde and the Tu-144, also used afterburners as does Scaled Composites White Knight, a carrier aircraft for the experimental SpaceShipOne suborbital spacecraft.

Reheat was flight-trialled in 1944 on the W.2/700 engines in a Gloster Meteor I.[19]

Net thrust

The net thrust of a turbojet is given by:[20][21]

where:

| is the rate of flow of air through the engine | |

| is the rate of flow of fuel entering the engine | |

| is the speed of the jet (the exhaust plume) and is assumed to be less than sonic velocity | |

| is the true airspeed of the aircraft | |

| represents the nozzle gross thrust | |

| represents the ram drag of the intake |

If the speed of the jet is equal to sonic velocity the nozzle is said to be choked. If the nozzle is choked the pressure at the nozzle exit plane is greater than atmospheric pressure, and extra terms must be added to the above equation to account for the pressure thrust.[22]

The rate of flow of fuel entering the engine is very small compared with the rate of flow of air.[20] If the contribution of fuel to the nozzle gross thrust is ignored, the net thrust is:

The speed of the jet must exceed the true airspeed of the aircraft if there is to be a net forward thrust on the airframe. The speed can be calculated thermodynamically based on adiabatic expansion.[23]

Cycle improvements

The operation of a turbojet is modelled approximately by the Brayton cycle.

The efficiency of a gas turbine is increased by raising the overall pressure ratio, requiring higher-temperature compressor materials, and raising the turbine entry temperature, requiring better turbine materials and/or improved vane/blade cooling. It is also increased by reducing the losses as the flow progresses from the intake to the propelling nozzle. These losses are quantified by compressor and turbine efficiencies and ducting pressure losses. When used in a turbojet application, where the output from the gas turbine is used in a propelling nozzle, raising the turbine temperature increases the jet velocity. This reduces the propulsive efficiency, giving a loss in overall efficiency, as reflected by the higher fuel consumption, or SFC.[24]

See also

- Air start system

- Exoskeletal engine

- Jet dragster

- Turbojet development at the RAE

- Turbine engine failure

- Variable cycle engine

References

- ↑ "Turbojet Engine". NASA Glenn Research Center. Retrieved 2009-05-06.

- ↑ Maxime Guillaume,"Propulseur par réaction sur l'air," French patent FR 534801 (filed: 3 May 1921; issued: 13 January 1922)

- ↑ "Chasing the Sun - Frank Whittle". PBS. Retrieved 2010-03-26.

- ↑ "History - Frank Whittle (1907 - 1996)". BBC. Retrieved 2010-03-26.

- ↑ Frank Whittle, "Improvements relating to the propulsion of aircraft and other vehicles," British patent no. 347,206 (filed: 16 January 1930). Available on-line at: http://v3.espacenet.com/origdoc?DB=EPODOC&IDX=GB347206&F=0&QPN=GB347206 .

- ↑ Experimental & Prototype US Air Force Jet Fighters, Jenkins & Landis, 2008

- ↑ Warsitz, Lutz: THE FIRST JET PILOT - The Story of German Test Pilot Erich Warsitz (p. 125), Pen and Sword Books Ltd., England, 2009 ISBN 978-1-84415-818-8

- ↑ Larson, George C. (April–May 2010), "Old Faithful", "Air & Space", 25 (1): 80

- ↑ "World Encyclopedia of Aero Engines - 5th edition" by Bill Gunston, Sutton Publishing, 2006, p.192

- ↑ sir alec | flame tubes | marshal sir | 1949 | 0598 | Flight Archive

- ↑ Sims, C.T., Chester, A History of Superalloy Metallurgy, Proc. 5th Symp. on Superalloys, 1984.

- ↑ "Rolls-Royce Derwent | 1945". Flight. Flightglobal.com: 448. 1945-10-25. Retrieved 2013-12-14.

- ↑ Robert V. Garvin, "Starting Something Big", ISBN 978-1-56347-289-3, p.5

- ↑ "Test Pilot" Brian Trubshaw, Sutton Publishing 1999, ISBN 0 7509 1838 1, Appendix VIIIb

- ↑ http://www.enginehistory.org/Convention/2013/HowInletsWork8-19-13.pdf Fig.26

- ↑ "Trade-offs in Jet Inlet Design" Sobester, Journal of Aircraft Vol.44, No.3, May–June 2007, Fig.12

- ↑ 1960 | Flight | Archive

- ↑ 1947 | 1359 | Flight Archive

- ↑ "World Encyclopedia of Aero Engines - 5th edition" by Bill Gunston, Sutton Publishing, 2006, p.160

- 1 2 Cumpsty, Nicholas (2003). "3.1". Jet Propulsion (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-54144-1.

- ↑ "Turbojet Thrust". NASA Glenn Research Center. Retrieved 2009-05-06.

- ↑ Cumpsty, Jet Propulsion, Section 6.3

- ↑ MIT.EDU Unified: Thermodynamics and Propulsion Prof. Z. S. Spakovszky - Turbojet Engine

- ↑ "Gas Turbine Theory" Cohen, Rogers, Saravanamuttoo, ISBN 0 582 44927 8, p72-73, fig 3.11

Further reading

- Springer, Edwin H. (2001). Constructing A Turbocharger Turbojet Engine. Turbojet Technologies.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Turbojet engines. |

- Erich Warsitz, the world's first jet pilot: includes rare videos (Heinkel He 178) and audio commentaries

- NASA Turbojet Engine Description: includes a software model

- Possibilities of Jet Propulsion: 1941 survey with discussion of experimental designs of the 1920s and 1930s.

- Whittle Power Jet Papers - Correspondence from the archives of Peterhouse College relating to the development of Whittle's Turbojet engine in Cambridge Digital Library