Tulip

| Tulip | |

|---|---|

| |

| Cultivated tulip – Floriade 2005, Canberra | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Monocots |

| Order: | Liliales |

| Family: | Liliaceae |

| Subfamily: | Lilioideae |

| Genus: | Tulipa L. |

| Type species | |

| Tulipa gesneriana L. | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

| |

The tulip is a Eurasian and North African genus of herbaceous, perennial, bulbous plants in the lily family,[1] with showy flowers. About 75 wild species are currently accepted.[2]

The genus's native range extends west to the Iberian Peninsula, through North Africa to Greece, the Balkans, Turkey, throughout the Levant (Syria, Israel, Palestinian Territories, Lebanon, Jordan) and Iran, north to Ukraine, southern Siberia and Mongolia, and east to the Northwest of China.[1][2] The tulip's centre of diversity is in the Pamir, Hindu Kush, and Tien Shan mountains.[3] It is a common element of steppe and winter-rain Mediterranean vegetation.

A number of species and many hybrid cultivars are grown in gardens or as potted plants.

Description

Tulips are spring-blooming perennials that grow from bulbs. Depending on the species, tulip plants can be between 4 inches (10 cm) and 28 inches (71 cm) high. The tulip's flowers usually bloom on scapes with leaves in a rosette at ground level and a single flowering stalk arising from amongst the leaves. Tulip stems have few leaves. Larger species tend to have multiple leaves. Plants typically have two to six leaves, some species up to 12. The tulip's leaf is strap-shaped, with a waxy coating, and the leaves are alternately arranged on the stem; these fleshy blades are often bluish green in colour. Most tulips produce only one flower per stem, but a few species bear multiple flowers on their scapes (e.g. Tulipa turkestanica). The generally cup or star-shaped tulip flower has three petals and three sepals, which are often termed tepals because they are nearly identical. These six tepals are often marked on the interior surface near the bases with darker colourings. Tulip flowers come in a wide variety of colours, except pure blue (several tulips with "blue" in the name have a faint violet hue).[4][5]

The flowers have six distinct, basifixed stamens with filaments shorter than the tepals. Each stigma has three distinct lobes, and the ovaries are superior, with three chambers. The tulip's seed is a capsule with a leathery covering and an ellipsoid to globe shape. Each capsule contains numerous flat, disc-shaped seeds in two rows per chamber.[6] These light to dark brown seeds have very thin seed coats and endosperm that does not normally fill the entire seed.[7]

Phytochemistry

Tulipanin is an anthocyanin found in tulips. It is the 3-rutinoside of delphinidin. The chemical compounds named tuliposides and tulipalins can also be found in tulips and are responsible for allergies.[8] Tulipalin A, or α-methylene-γ-butyrolactone, is a common allergen, generated by hydrolysis of the glucoside tuliposide A. It induces a dermatitis that is mostly occupational and affects tulip bulb sorters and florists who cut the stems and leaves.[9] Tulipanin A and B are toxic to horses, cats and dogs.[10]

Taxonomy

The genus Tulipa was traditionally divided into two sections, Eriostemones and Tulipa (as Leiostemones),[11] and comprises ca. 76 species.[2]

In 1997, the two sections were raised to subgenera and subgenus Tulipa was divided into five sections:

- Clusianae

- Eichleres

- subdivided into eight series

- Kopalkowskiana

- Tulipanum

- Tulipa

Subgenus Eriostemones was divided into the sections:

- Biflores

- Sylvestres

- Saxatiles

In 2009, two other subgenera were proposed, Clusianae and Orithyia,[12] and this total of four subgenera was corroborated by a recent study (Christenhusz et al. 2013[2]). That study did not find support for any of the previous sections proposed, and since hybridisation is relatively common, it is probably better to refrain from subdividing the subgenera any further. Some species formerly classified as Tulipa are now considered as the separate genus Amana, including Amana edulis (Tulipa edulis). These species are more closely allied to Erythronium.[13]

Species

The classification into four subgenera below is based on Christenhusz et al. (2013).[2]

This list was used as the basis for The Genus Tulipa. Tulips of the World.[14]

Subgenus Clusianae

- Tulipa clusiana Redouté (lady tulip) - Greece, Iran, Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan, W Himalayas

- Tulipa harazensis Rech.f. - Iran

- Tulipa linifolia Regel (Bokhara tulip) - Iran, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan

- Tulipa montana Lindl. - Turkmenistan, Iran

Subgenus Orithyia

- Tulipa heteropetala Ledeb. - Altay Krai, Kazakhstan, Xinjiang

- Tulipa heterophylla (Regel) Baker - Kazakhstan, Xinjiang, Kyrgyzstan

- Tulipa sinkiangensis Z.M.Mao - Xinjiang

- Tulipa uniflora (L.) Besser ex Baker (Siberian tulip) - Siberia, Mongolia, Xinjiang, Inner Mongolia, Kazakhstan

Subgenus Tulipa

- Tulipa agenensis Redouté (eyed tulip) - Greece, Middle East

- Tulipa albanica Kit Tan & Shuka (Albanian tulip) - Albania

- Tulipa alberti Regel (Albert's tulip) - - Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan

- Tulipa aleppensis Boiss. ex Regel (Aleppo tulip)- Turkey, Syria, Lebanon

- Tulipa altaica Pall. ex Spreng. (Altai tulip) - Altai Krai, Western Siberia, Kazakhstan, Xinjiang

- Tulipa anisophylla Vved. - Tajikistan

- Tulipa armena Boiss. (Armenian tulip) - Turkey, Iran, South Caucasus

- Tulipa banuensis Grey-Wilson (Afghan tulip) - Afghanistan

- Tulipa borszczowii Regel - Kazakhstan

- Tulipa botschantzevae S.N.Abramova & Zakal. - Turkmenistan, Iran

- Tulipa butkovii Botschantz. - Uzbekistan

- Tulipa carinata Vved. (Pamir tulip) - Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Afghanistan

- Tulipa cypria Stapf ex Turrill (Cyprian tulip) - Cyprus

- Tulipa dubia Vved. - Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan

- Tulipa faribae Ghahr., Attar & Ghahrem.-Nejad - Iran

- Tulipa ferganica Vved. - Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan

- Tulipa foliosa - Turkey

- Tulipa fosteriana W.Irving - Afghanistan, Central Asia

- Tulipa × gesneriana L. (garden tulip)

- Tulipa greigii Regel (maculate tulip) - Iran, Central Asia

- Tulipa heweri Raamsd. - Afghanistan

- Tulipa hissarica Popov & Vved. - Tajikistan, Uzbekistan

- Tulipa hoogiana B.Fedtsch. - Turkmenistan, Iran

- Tulipa hungarica Borbás (Rhodope tulip) - Hungary, Serbia, Bulgaria

- Tulipa iliensis Regel - Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Xinjiang

- Tulipa ingens (Tubergen's tulip) - Tajikistan, Uzbekistan

- Tulipa julia K.Koch (Julia tulip) - Turkey, South Caucasus, Syria, Lebanon

- Tulipa kaufmanniana Regel (waterlily tulip) - Central Asia

- Tulipa kolpakowskiana Regel (sun tulip)[15] - Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Xinjiang, Afghanistan

- Tulipa korolkowii Regel - Central Asia

- Tulipa kosovarica Kit Tan, Shuka & Krasniqi - Kosovo

- Tulipa kuschkensis B.Fedtsch. - Turkmenistan, Afghanistan, Iran

- Tulipa lanata Regel - Tajikistan, Afghanistan, Pakistan, W Himalayas

- Tulipa lehmanniana Merckl. (Lehmann's tulip) - Afghanistan, Iran, Central Asia

- Tulipa lemmersii - Kazakhstan

- Tulipa ostrowskiana Regel - Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan

- Tulipa persica (Lindl.) Sweet (Persian tulip) - Iran

- Tulipa platystemon Vved. - Kyrgyzstan

- Tulipa praestans H.B.May (multiflowered tulip) - Tajikistan

- Tulipa scardica Bornm. (Balkan tulip) - Kosovo, Greece

- Tulipa scharipovii Tojibaev - Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan

- Tulipa schmidtii Fomin - Iran, South Caucasus

- Tulipa serbica Tatic & Krivošej - Kosovo, Serbia

- Tulipa sosnowskyi Achv. & Mirzoeva - South Caucasus

- Tulipa suaveolens (= Tulipa schrenkii) Roth (Scented or Crimean tulip, Schrenck's tulip) - Ukraine, Crimea, Russia and south of Siberia, Caucasus, Iran, Kazakhastan

- Tulipa subquinquefolia Vved. - Tajikistan, Uzbekistan

- Tulipa systola Stapf - Middle East

- Tulipa talassica Lazkov - Kyrgyzstan

- Tulipa tetraphylla Regel - Xinjiang, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan

- Tulipa × tschimganica Botschantz. - Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan

- Tulipa ulophylla Wendelbo - Iran

- Tulipa undulatifolia Boiss. (Eichler's tulip) - Greece, Balkans, Caucasus, Middle East, Iran, Central Asia

- Tulipa uzbekistanica Botschantz. & Sharipov - Uzbekistan

- Tulipa vvedenskyi Botschantz. - Tajikistan

Subgenus Eriostemones

- Tulipa biflora Pall. (two-flowered tulip) - Macedonia, Egypt, Crimea, Russia, Asia from Saudi Arabia to Xinjiang + Western Siberia

- Tulipa bifloriformis Vved. - Central Asia

- Tulipa cinnabarina K.Perss. - Turkey

- Tulipa cretica Boiss. & Heldr. (Cretan tulip) - Crete

- Tulipa dasystemon (Regel) Regel - Central Asia, Xinjiang

- Tulipa humilis Herb. (rainbow tulip) - Caucasus, Middle East

- As of May 2015, the World Checklist of Selected Plant Families accepts some species which other sources include in T. humilis:[16]

- Tulipa aucheriana Baker – E. Turkey to Afghanistan

- Tulipa kurdica Wendelbo – N. Iraq

- Tulipa pulchella (Regel) Baker – S. & S.E. Turkey to N. Iran

- Tulipa violacea Boiss. & Buhse – S.E. Transcaucasus

- Tulipa kolbintsevii Zonn. - Kazakhstan

- Tulipa koyuncui Eker & Babaç - Turkey

- Tulipa orithyioides Vved. - Central Asia

- Tulipa orphanidea Boiss. & Heldr. (green or orange wild tulip) - Greece, Bulgaria, Turkey

- Tulipa regelii Krassn. (licate or Regel's tulip) - Kazakhstan

- Tulipa saxatilis Sieber ex Spreng. (rock tulip) - Greece, Turkey

- Tulipa sprengeri Baker - Turkey

- Tulipa sylvestris L. (wild tulip) - Eurasia from Portugal to Xinjiang

- Tulipa turkestanica (Regel) Regel - Central Asia, Xinjiang

- Tulipa urumiensis Stapf (tarda tulip) - Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Iran

Unplaced

- The horned tulip is often offered in the trade as "Tulipa acuminata", but is in fact a cultivar, unknown from the wild, and should be distributed under its correct cultivar name: Tulipa 'Cornuta'.[2]

- Tulipa boettgeri Regel – Central Asia; accepted by the World Checklist of Selected Plant Families as of May 2015,[16] but regarded as unplaced by Christenhusz et al.[2]

Species not belonging to the genus Tulipa; classified in other genera

- Tulipa anhuiensis X.S.Shen, now: Amana anhuiensis (X.S.Shen) Christenh.

- Tulipa breyniana L., now: Moraea collina Thunb. (Iridaceae).

- Tulipa edulis (Miq.) Baker, now: Amana edulis (Miq.) Honda.

- Tulipa erythronioides Baker, now: Amana erythronioides (Baker) D.Y.Tan & D.Y.Hong.

- Tulipa graminifolia Baker ex S.Moore, now: Amana edulis (Miq.) Honda.

- Tulipa latifolia (Makino) Makino, now: Amana erythronioides (Baker) D.Y.Tan & D.Y.Hong

- Tulipa ornithogaloides Fisch. ex Besser, now: Gagea triflora (Ledeb.) Schult. & Schult.f.

- Tulipa pudica (Pursh) Raf., now: Fritillaria pudica (Pursh) Spreng.

- Tulipa sibthorpiana Sm., now: Fritillaria sibthorpiana (Sm.) Baker.

"Species tulips"

The terms "species tulips" and "botanical tulips" refer to wild species in contrast to hybridised varieties.[17] As a group they have been described as being less ostentatious but more reliably vigorous as they age.[18][19]

Etymology

The word tulip, first mentioned in western Europe in or around 1554 and seemingly derived from the "Turkish Letters" of diplomat Ogier Ghiselin de Busbecq, first appeared in English as tulipa or tulipant, entering the language by way of French: tulipe and its obsolete form tulipan or by way of Modern Latin tulīpa, from Ottoman Turkish tülbend ("muslin" or "gauze"), and may be ultimately derived from the Persian: دلبند delband ("Turban"), this name being applied because of a perceived resemblance of the shape of a tulip flower to that of a turban.[20] This may have been due to a translation error in early times, when it was fashionable in the Ottoman Empire to wear tulips on turbans. The translator possibly confused the flower for the turban.[2]

Distribution and habitat

Tulips are indigenous to mountainous areas with temperate climates and need a period of cool dormancy, known as vernalisation. They thrive in climates with long, cool springs and dry summers. Tulip bulbs imported to warm-winter areas are often planted in autumn to be treated as annuals.

Ecology

Botrytis tulipae is a major fungal disease affecting tulips, causing cell death and eventually the rotting of the plant.[21] Other pathogens include anthracnose, bacterial soft rot, blight caused by Sclerotium rolfsii, bulb nematodes, other rots including blue molds, black molds and mushy rot.[22]

The fungus Trichoderma viride can infect tulips, producing dried leaf tips and reduced growth, although symptoms are usually mild and only present on bulbs growing in glasshouses.

Variegated tulips admired during the Dutch tulipomania gained their delicately feathered patterns from an infection with the tulip breaking virus, a mosaic virus that was carried by the green peach aphid, Myzus persicae. While the virus produces fantastically streaked flowers, it also weakens plants and reduces the number of offsets produced. Tulips affected by mosaic virus are called "broken"; while such plants can occasionally revert to a plain or solid colouring, they will remain infected and have to be destroyed. Today the virus is almost eradicated from tulip growers' fields. The multicoloured patterns or modern varieties result from breeding; they normally have solid, not feathered borders between the colours.

Cultivation

History

Islamic World

Cultivation of the tulip began in Persia, probably in the 10th century.[2] Early cultivars must have emerged from hybridisation in gardens from wild collected plants, which were then favoured, possibly due to flower size or growth vigour. The tulip is not mentioned by any writer from antiquity,[24] therefore it seems probable that tulips were introduced into Anatolia only with the advance of the Seljuks.[24] In the Ottoman Empire, numerous types of tulips were cultivated and bred,[25] and today, 14 species can still be found in Turkey.[24] Tulips are mentioned by Omar Kayam and Celaleddin Rûmi.[24]

In 1574, Sultan Selim II. ordered the Kadi of A‘azāz in Syria to send him 50,000 tulip bulbs. However, Harvey points out several problems with this source, and there is also the possibility that tulips and hyacinth (sümbüll), originally Indian spikenard (Nardostachys jatamansi) have been confused.[26] Sultan Selim also imported 300,000 bulbs of Kefe Lale (also known as Cafe-Lale, from the medieval name Kaffa, probably Tulipa schrenkii) from Kefe for his gardens in the Topkapı Sarayı in Istanbul.[27]

Sultan Ahmet III maintained famous tulip gardens in the summer highland pastures (Yayla) at Spil Dağı above the town of Manisa.[28] They seem to have consisted of wild tulips. However, from the 14 tulip species known from Turkey, only four are considered to be of local origin,[29] so wild tulips from Iran and Central Asia may have been brought into Turkey during the Seljuk and especially Ottoman periods. Sultan Ahmet also imported domestic tulip bulbs from the Netherlands.

The gardening book Revnak'ı Bostan (Beauty of the Garden) by Sahibül Reis ülhaç Ibrahim Ibn ülhaç Mehmet, written in 1660 does not mention the tulip at all, but contains advice on growing hyacinths and lilies.[30] However, there is considerable confusion of terminology, and tulips may have been subsumed under hyacinth, a mistake several European botanists were to perpetuate. In 1515, the scholar Qasim from Herat in contrast had identified both wild and garden tulips (lale) as anemones (shaqayq al-nu'man), but described the crown imperial as laleh kakli.[30]

In a Turkic text written before 1495, the Chagatay Husayn Bayqarah mentions tulips (lale).[31] Babur, the founder of the Mughal Empire, also names tulips in the Baburnama.[32] He may actually have introduced them from Afghanistan to the plains of India, as he did with other plants like melons and grapes.[33]

In Moorish Andalus, a "Makedonian bulb" (basal al-maqdunis) or "bucket-Narcissus" (naryis qadusi) was cultivated as an ornamental plant in gardens. It was supposed to have come from Alexandria and may have been Tulipa sylvestris, but the identification is not wholly secure.[34]

Introduction to Western Europe

Although it is unknown who first brought the tulip to Northwestern Europe, the most widely accepted story is that it was Oghier Ghislain de Busbecq, an ambassador for Emperor Ferdinand I to Suleyman the Magnificent. According to a letter, he saw "an abundance of flowers everywhere; Narcissus, hyacinths and those in Turkish called Lale, much to our astonishment because it was almost midwinter, a season unfriendly to flowers."[35][36] However, in 1559, an account by Conrad Gessner describes tulips flowering in Augsburg, Swabia in the garden of Councillor Heinrich Herwart. In Central and Northern Europe, tulip bulbs are generally removed from the ground in June and must be replanted by September for the winter. It is doubtful that Busbecq could have had the tulip bulbs harvested, shipped to Germany and replanted between March 1558 and Gessner's description the following year. Pietro Andrea Mattioli illustrated a tulip in 1565 but identified it as a narcissus, however.

Carolus Clusius is largely responsible for the spread of tulip bulbs in the final years of the sixteenth century. He planted tulips at the Vienna Imperial Botanical Gardens in 1573. He finished the first major work on tulips in 1592, and made note of the variations in colour. After he was appointed director of the Leiden University's newly established Hortus Botanicus, he planted both a teaching garden and his private garden with tulips in late 1593. Thus, 1594 is considered the date of the tulip's first flowering in the Netherlands, despite reports of the cultivation of tulips in private gardens in Antwerp and Amsterdam two or three decades earlier. These tulips at Leiden would eventually lead to both the Tulip mania and the tulip industry in the Netherlands.[37] In 1596 and 1598, over a hundred bulbs were stolen from his garden in a single raid.

Between 1634 and 1637, the enthusiasm for the new flowers triggered a speculative frenzy now known as the tulip mania. Tulip bulbs became so expensive that they were treated as a form of currency, or rather, as futures. Around this time, the ceramic tulipiere was devised for the display of cut flowers stem by stem. Vases and bouquets, usually including tulips, often appeared in Dutch still-life painting. To this day, tulips are associated with the Netherlands, and the cultivated forms of the tulip are often called "Dutch tulips." The Netherlands have the world's largest permanent display of tulips at the Keukenhof.

Tulip cultivars have usually several species in their direct background, but most have been derived from Tulipa suaveolens, often erroneously listed as Tulipa schrenkii. Tulipa gesneriana is in itself an early hybrid of complex origin and is probably not the same taxon as was described by Conrad Gessner in the 16th century.[2]

Introduction to the United States

It is believed the first tulips in the United States were grown near Spring Pond at the Fay Estate in Lynn and Salem, Massachusetts. From 1847 to 1865, Richard Sullivan Fay, Esq., one of Lynn's wealthiest men, settled on 500 acres (2.0 km2) located partly in present-day Lynn and partly in present-day Salem. Mr. Fay imported many different trees and plants from all parts of the world and planted them among the meadows of the Fay Estate.[38]

Propagation

Tulips can be propagated through bulb offsets, seeds or micropropagation.[39] Offsets and tissue culture methods are means of asexual propagation for producing genetic clones of the parent plant, which maintains cultivar genetic integrity. Seeds are most often used to propagate species and subspecies or to create new hybrids. Many tulip species can cross-pollinate with each other, and when wild tulip populations overlap geographically with other tulip species or subspecies, they often hybridise and create mixed populations. Most commercial tulip cultivars are complex hybrids, and often sterile.

Offsets require a year or more of growth before plants are large enough to flower. Tulips grown from seeds often need five to eight years before plants are of flowering size. Commercial growers usually harvest the tulip bulbs in late summer and grade them into sizes; bulbs large enough to flower are sorted and sold, while smaller bulbs are sorted into sizes and replanted for sale in the future. The Netherlands are the world's main producer of commercial tulip plants, producing as many as 3 billion bulbs annually, the majority for export.[40]

Horticultural classification

In horticulture, tulips are divided up into fifteen groups (Divisions) mostly based on flower morphology and plant size.[41][42]

- Div. 1: Single early – with cup-shaped single flowers, no larger than 8 cm across (3 inches). They bloom early to mid season. Growing 15 to 45 cm tall.

- Div. 2: Double early – with fully double flowers, bowl shaped to 8 cm across. Plants typically grow from 30–40 cm tall.

- Div. 3: Triumph – single, cup shaped flowers up to 6 cm wide. Plants grow 35–60 cm tall and bloom mid to late season.

- Div. 4: Darwin hybrid – single flowers are ovoid in shape and up to 8 cm wide. Plants grow 50–70 cm tall and bloom mid to late season. This group should not be confused with older Darwin tulips, which belong in the Single Late Group below.

- Div. 5: Single late – cup or goblet-shaded flowers up to 8 cm wide, some plants produce multi-flowering stems. Plants grow 45–75 cm tall and bloom late season.

- Div. 6: Lily-flowered – the flowers possess a distinct narrow 'waist' with pointed and reflexed petals. Previously included with the old Darwins, only becoming a group in their own right in 1958.[43]

- Div. 7: Fringed (Crispa)

- Div. 8: Viridiflora

- Div. 9: Rembrandt

- Div. 10: Parrot

- Div. 11: Double late – Large, heavy blooms. They range from 18 to 22 inches tall.

- Div. 12: Kaufmanniana – Waterlily tulip. Medium-large creamy yellow flowers marked red on the outside and yellow at the center. Stems 6 in. tall.

- Div. 13: Fosteriana (Emperor)

- Div. 14: Greigii – Scarlet flowers 6 in. across, on 10 in. stems. Foliage mottled with brown.[44]

- Div. 15: Species (Botanical)

- Div. 16: Multiflowering – not an official division, these tulips belong in the first 15 divisions but are often listed separately because they have multiple blooms per bulb.

They may also be classified by their flowering season:[45]

- Early flowering: Single Early Tulips, Double Early Tulips, Greigii Tulips, Kaufmanniana Tulips, Fosteriana Tulips, § Species tulips

- Mid-season flowering: Darwin Hybrid Tulips, Triumph Tulips, Parrot Tulips

- Late season flowering: Single Late Tulips, Double Late Tulips, Viridiflora Tulips, Lily-flowering Tulips, Fringed Tulips, Rembrandt Tulips

Neo-tulipae

A number of names are based on naturalised garden tulips, and are usually referred to as neo-tulipae. These are often difficult to trace back to their original cultivar, and in some cases have been occurring in the wild for many centuries. The history of naturalisation is unknown, but populations are usually associated with agricultural practices and are possibly linked to saffron cultivation . Some neo-tulipae have been brought into cultivation, and are often offered as botanical tulips. These cultivated plants can be classified into two Cultivar Groups: 'Grengiolensis Group', with picotee tepals, and the 'Didieri Group' with unicolourous tepals.

Horticulture

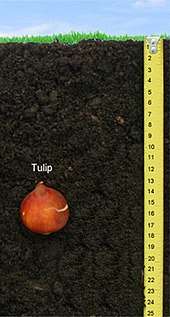

Tulip bulbs are typically planted around late summer and fall, in well-drained soils. Tulips should be planted 4 to 6 inches (10 to 15 cm) apart from each other. The recommended hole depth is 4 to 8 inches (10 to 20 cm) deep, and is measured from the top of the bulb to the surface. Therefore, larger tulip bulbs would require deeper holes.[46] Species tulips are normally planted deeper.

Culture

_(5282772890).jpg)

The tulip was a topic for Persian poets from the thirteenth century. In the poem Gulistan by Musharrifu'd-din Saadi, described a visionary garden paradise with "The murmur of a cool stream / bird song, ripe fruit in plenty / bright multicoloured tulips and fragrant roses..."[47] The gift of a red or yellow tulip was a declaration of love, the flower's black center representing a heart burned by passion.[48] In recent times, tulips have featured in the poems of Simin Behbahani.

Tulips are called lale in Turkish (from Persian: "lale" لاله). When written in Arabic letters, "lale" has the same letters as Allah, which is why the flower became a holy symbol. It was also associated with the House of Osman, resulting in tulips being widely used in decorative motifs on tiles, mosques, fabrics, crockery, etc. in the Ottoman Empire.[2] The tulip was seen as a symbol of abundance and indulgence. The era during which the Ottoman Empire was wealthiest is often called the Tulip era or Lale Devri in Turkish.

The shape of emblem of Iran is chosen to resemble a tulip, in memory of the people who died for Iran.

Tulips became popular garden plants in east and west, but, whereas the tulip in Turkish culture was a symbol of paradise on earth and had almost a divine status, in the Netherlands it represented the briefness of life.[2]

The Black Tulip is a historical romance by Alexandre Dumas, père. The story takes place in the Dutch city of Haarlem, where a reward is offered to the first grower who can produce a truly black tulip.

The Tulip is also viewed prominently in a number of the Major Arcana cards of the Oswald Wirth Tarot deck. Specifically: Arcanas Zero, One, Four, and Fifteen.

Today, Tulip festivals are held around the world, for example in the Netherlands and Spalding, England. There is also a popular festival in Morges, Switzerland. Every spring, there are tulip festivals in North America, including the Tulip Time Festival in Holland, Michigan, the Skagit Valley Tulip Festival in Skagit Valley, Washington, the Tulip Time Festival in Orange City and Pella, Iowa, and the Canadian Tulip Festival in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. Tulips are also popular in Australia and several festivals are held in September and October, during the Southern Hemisphere's spring.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Kew World Checklist of Selected Plant Families

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Christenhusz, Maarten J.M.; Govaerts, Rafaël; David, John C.; Hall, Tony; Borland, Katherine; Roberts, Penelope S.; Tuomisto, Anne; Buerki, Sven; Chase, Mark W.; Fay, Michael F. (2013). "Tiptoe through the tulips – cultural history, molecular phylogenetics and classification of Tulipa (Liliaceae)". Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society. 172 (3): 280–328. doi:10.1111/boj.12061.

- ↑ King, Michael (2005). Gardening with Tulips. Portland, OR: Timber Press. p. 16. ISBN 0-88192-744-9.

- ↑ King (2005), p. 164

- ↑ Tenenbaum, Frances, ed. (2003). Taylor's Encyclopedia of Garden Plants. Houghton Mifflin. p. 395. ISBN 0-618-22644-3.

- ↑ Flora of North America Editorial Committee. 2002. Flora of North America. North of Mexico Vol. 26, orchidales. New York: Oxford University Press. Page 199

- ↑ Botschantzeva, Z. P. (1982). Tulips: taxonomy, morphology, cytology, phytogeography and physiology. CRC Press. p. 120. ISBN 90-6191-029-3.

- ↑ Christensen, L. P.; Kristiansen, K. (1999). "Isolation and quantification of tuliposides and tulipalins in tulips (Tulipa) by high-performance liquid chromatography". Contact dermatitis. 40 (6): 300–9. PMID 10385332. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1999.tb06080.x.

- ↑ Sasseville, D (2009). "Dermatitis from plants of the new world". European Journal of Dermatology. 19 (5): 423–30. PMID 19487175. doi:10.1684/ejd.2009.0714.

- ↑ "Tulip". ASPCA. Retrieved 2013-04-01.

- ↑ Southern, David I. (1967). "Species relationships in the genus Tulipa". Chromosoma. 23: 80. doi:10.1007/BF00293313.

- ↑ Zonneveld, Ben J. M. (2009). "The systematic value of nuclear genome size for "all" species of Tulipa L. (Liliaceae)". Plant Systematics and Evolution. 281: 217. doi:10.1007/s00606-009-0203-7.

- ↑ Clennett et al 2012.

- ↑ Everett, D. (2013). The genus Tulipa. Tulips of the World. Kew Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84246-481-6.

- ↑ "Kolpakowski Tulip, aka Sun Tulip". www.paghat.com. Retrieved 24 July 2014.

- 1 2 3 "Search for Tulipa". World Checklist of Selected Plant Families. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Retrieved 2015-05-05.

- ↑ Eyster, William H. (1950). "The 'Species' Tulips". Organic Gardening. 16–17: 22. Retrieved 31 May 2017.

- ↑ Bales, Suzanne F. (1992). Bulbs. Macmillan General Reference. p. 74. ISBN 9780671863920.

- ↑ Fell, Derek (1990). The Easiest Flowers to Grow. Ortho Books. p. 97. ISBN 9780897212205.

- ↑ "Tulip". Etymplogy Online. Retrieved July 24, 2017.

- ↑ Reyes, A. Leon; Prins, T. P.; van Empel, J.-P.; van Tuyl, J. M. "Differences in Epicuticular Wax Layer in Tulip Can Influence Resistance to Botrytis Tulipae". Acta Horticulturae. 673: 457–46. doi:10.17660/ActaHortic.2005.673.59.

- ↑ Westcott, Cynthia; Horst, R. Kenneth (1979). Westcott's Plant disease handbook. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold. p. 709. ISBN 0-442-23543-7.

- ↑ Illustration of Tulipa sylvestris subsp. australis, as Tulipa breyniana (Cape tulip). Date: 1804. Source Curtis's botanical magazine vol. 19 plate. 717 (http://www.botanicus.org/page/471019). Artists: Sydenham Edwards (1768-1819) & F. Sansom

- 1 2 3 4 Mathew, Brian; Baytop, Turhan (1984). The Bulbous Plants of Turkey. Frome: Batsford. p. 100. ISBN 978-0713445176.

- ↑ Eken, Ahmet (2002). Artık Göremediğimiz Bir Çiçek İstanbul Lâlesi, Hedef, Nisan p. 83

- ↑ Harvey, John H. (1976). "Turkey as a Source of Garden Plants". Garden History. 4 (3): 24. JSTOR 1586521. doi:10.2307/1586521.

- ↑ Pavord, Anna (1999). The Tulip. London: Bloomsbury. p. 41.

- ↑ Harvey (1976), pp. 21ff.

- ↑ Wilford, Richard. Tulips. Species and hybrids for the gardener. Portland: Timber Press. p. 53.

- 1 2 Harvey (1976), p. 26

- ↑ Harvey (1976), p. 25

- ↑ Harvey (1976), p. 22

- ↑ Annette Susanne Beveridge, Babur-nama (Memoirs of Babur). Translated from the original Turki text of Zahiru'd-din Muhammad Babur Padsha Ghazo. Delhi 1921 (Reprint Low Price Publications 1989 in einem Band, ISBN 81-85395-07-1, 686

- ↑ Hernández Bermejo, J. Esteban; García Sánchez, Expiración (2009). "Tulips: An Ornamental Crop in the Andalusian Middle Ages". Economic Botany. 63 (1): 60–66. JSTOR 40390435.

- ↑ Blunt, Wilfrid. Tulipomania. p. 7.

- ↑ Forster, E. S. (trans. et ed.) (1927). The Turkish Letters of Ogier Ghiselin de Busbecq. Oxford.

- ↑ "How A Turkish Blossom Enflamed the Dutch Landscape". The New York Times. 2001-03-04. Retrieved 2012-03-14.

- ↑ The Daily Item, Lynn, Mass. Independent Newspaper, January 24, 1952

- ↑ Nishiuchi, Y. (1986). "Multiplication of Tulip Bulb by Tissue Culture in vitro". ISHS Acta Horticulturae. 177: 279–284. doi:10.17660/ActaHortic.1986.177.40.

- ↑ "Tulipa spp". Floridata. Retrieved 2009-12-07.

- ↑ Brickell, Christopher; Zuk, Judith D. (1997). The American Horticultural Society A–Z encyclopedia of garden plants. New York, N.Y.: DK Pub. p. 1028. ISBN 0-7894-1943-2.

- ↑ "Tulips". The Plant Expert. 2008-10-15. Retrieved 2012-03-14.

- ↑ Pavord, A. (1999). The Tulip. Bloomsbury. p. 352. ISBN 0-7475-4296-1.

- ↑ The Western Garden Book (Third ed.). Menlo Park, CA: Lane Magazine & Book Company. 1972. p. 448.

- ↑ Jauron, Richard. "Tulip Classes". Iowa State University. Retrieved 2012-03-14.

- ↑ "How To Grow The Perfect Tulip".

- ↑ Pavord (1999), p. 31

- ↑ "Meaning of flowers". Retrieved 2012-05-01.

Bibliography

Books

- Blunt, Wilfrid. Tulipomania

- Clusius, Carolus. A Treatise on Tulips

- Dash, Mike. Tulipomania

- Everett, Diana. The genus Tulipa. Tulips of the World

- Goldgar, Anne (2007). Tulipmania: money, honor, and knowledge in the Dutch golden age. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226301303. Retrieved 21 February 2015.

- King, Michael. Gardening with Tulips (London, Frances Lincoln 2005)

- Pavord, Anna, The tulip (London, Bloomsbury 1999)

- Pollan, Michael. The Botany of Desire

- Papiomitoglou, Vaggelis. Wild flowers of Greece (Mediterraneo Editions 2006), ISBN 960-8227-74-7

Articles

- Christenhusz, Maarten J.M.; Govaerts, Rafaël; David, John C.; Hall, Tony; Borland, Katherine; Roberts, Penelope S.; Tuomisto, Anne; Buerki, Sven; Chase, Mark W.; Fay, Michael F. (2013). "Tiptoe through the tulips – cultural history, molecular phylogenetics and classification of Tulipa (Liliaceae)". Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society. 172 (3): 280–328. doi:10.1111/boj.12061.

- Eker, İsmail; Babaç, Mehmet Tekin; Koyuncu, Mehmet (29 January 2014). "Revision of the genus Tulipa L. (Liliaceae) in Turkey". Phytotaxa. 157 (1): 001. doi:10.11646/phytotaxa.157.1.1.

- Tan, Dun-Yan; Zhang, Zhen; Li, Xin-Rong; Hong De-Yuan, De-Yuan (2005). "Restoration of the genus Amana Honda (Liliaceae) based on a cladistic analysis of morphological characters" (PDF). Acta Phytotaxonomica Sinica (in Chinese). 43 (3): 262–270. doi:10.1360/aps040106. Retrieved 14 September 2015.

- Clennett, John C. B.; Chase, Mark W.; Forest, Félix; Maurin, Olivier; Wilkin, Paul (December 2012). "Phylogenetic systematics of Erythronium (Liliaceae): morphological and molecular analyses". Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society. 170 (4): 504–528. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8339.2012.01302.x.

- Turktas, Mine; Metin, Özge Karakaş; Baştuğ, Berk; Ertuğrul, Fahriye; Saraç, Yasemin Izgi; Kaya, Erdal (July 2013). "Molecular phylogenetic analysis of Tulipa (Liliaceae) based on noncoding plastid and nuclear DNA sequences with an emphasis on Turkey". Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society. 172 (3): 270–279. doi:10.1111/boj.12040.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tulip. |

| Wikisource has the text of The New Student's Reference Work article Tulip. |

- Canadian National Capital Commission: The Gift of Tulips

- Bulb flower production » Tulip, International Flower Bulb Centre

- Tulip Picture Book, International Flower Bulb Centre

- Veldkamp, J. F.; Zonneveld, B. J. M. (2011). "The infrageneric nomenclature of Tulipa (Liliaceae)". Plant Systematics and Evolution. 298: 87. doi:10.1007/s00606-011-0525-0.