Tsavo Man-Eaters

The Tsavo Man-Eaters were a pair of man-eating Tsavo lions responsible for the deaths of a number of construction workers on the Kenya-Uganda Railway from March through December 1898.

History

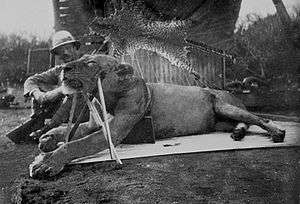

As part of the construction of a railway linking Uganda with the Indian Ocean at Kilindini Harbour, in March 1898 the British started building a railway bridge over the Tsavo River in Kenya. The project was led by Lieutenant-Colonel John Henry Patterson. During the next nine months of construction, two maneless male Tsavo lions stalked the campsite, dragging Indian workers from their tents at night and devouring them. Crews tried to scare off the lions and built campfires and bomas, or thorn fences, around their camp for protection to keep the man-eaters out, to no avail; the lions leaped over or crawled through the thorn fences. After the new attacks, hundreds of workers fled from Tsavo, halting construction on the bridge. Patterson set traps and tried several times to ambush the lions at night from a tree. After repeated unsuccessful attempts, he shot the first lion on 9 December 1898. Twenty days later, the second lion was found and killed. The first lion killed measured 9 feet 8 inches (2.95 m) from nose to tip of tail. It took eight men to carry the carcass back to camp. The construction crew returned and finished the bridge in February 1899. The exact number of people killed by the lions is unclear. Patterson gave several figures, overall claiming that there were 135 victims.[1][2]

Patterson writes in his account that he wounded the first lion with one bullet from a high-calibre rifle. This shot struck the lion in its back leg, but it escaped. Later, it returned at night and began stalking Patterson as he tried to hunt it. He shot it through the shoulder, penetrating its heart with a more powerful rifle and found it lying dead the next morning not far from his platform. The second lion was shot at most nine times, five with the same rifle, three with a second, and once with a third rifle.[3]

The first was fired from atop a scaffolding Patterson had built near goat kills done by the lion. Two, both from the second rifle were shot into it eleven days later as the lion was stalking Patterson and trying to flee. When they had found the lion the next day thereafter, Patterson shot it three more times with the same rifle, severely crippling it, and shot it three times with the third rifle, twice in the chest, and once in the head, which killed it. He claimed it died gnawing on a fallen tree branch, still trying to reach him.[3]

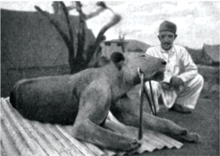

After 25 years as Patterson's floor rugs, the lions' skins were sold to the Chicago Field Museum in 1924 for a sum of $5,000. The skins arrived at the museum in very poor condition. The lions were then reconstructed and are now on permanent display along with their skulls.

Modern research

The two lion specimens in Chicago's Field Museum are known as FMNH 23970, the 'crouching' mount (killed 9 December 1898) and FMNH 23969, the 'standing' mount (killed 29 December 1898). Recent studies have been made upon the isotopic signature analysis of Δ13C and Nitrogen-15 in their bone collagen and hair keratin and published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. Using realistic assumptions on the consumable tissue per victim, lion energetic needs, and their assimilation efficiencies, researchers compared the man-eaters' Δ13C signatures to various reference standards: Tsavo lions with normal (wildlife) diets, grazers and browsers from Tsavo East and Tsavo West, and the skeletal remains of Taita people from the early 20th century. This analysis estimated that FMNH 23969 ate the equivalent of 10.5 humans and that FMNH 23970 ate 24.2 humans.[4]

This leads to the conclusion that the lower number of 35 victims is more likely and confirms the study published 8 years previously by Julian Kerbis Peterhans and Thomas Patrick Gnoske (2001) who estimated 28–31 victims. Although the scientific analysis does not differentiate between entire human corpses consumed, compared to parts of individual prey; as the attacks often raised alarm forcing the lions to slink back into the surrounding area. Many workers over the long construction period went missing, died in accidents, or simply left out of fear; so it is likely almost all of the builders, who stayed on, knew someone missing or supposedly eaten. It appears that Colonel Patterson may have exaggerated his claims as have subsequent investigators (e.g. "135 armed men", Neiburger and Patterson, 2000) (though none of these modern studies have taken into account the people who were killed but not eaten by the animals).[5] The diet of the victims would also affect their isotopic signature. A low meat diet would produce a signature more typical of herbivores in the victims, affecting the outcome of the test.[6] That fact is important to note since many of the workers at Tsavo were Hindus and may have had a vegetarian diet. This research also excludes, but does not disprove, the claims that the lions were not eating the victims they killed but merely killing just to kill. Similar claims have been made of other wildlife predators.

The earlier (2001) study by Tom Patrick Gnoske and Julian Kerbis Peterhans, published in the Journal of the East African Natural History Society (Kerbis Peterhans & Gnoske, 2001), contended that the proposed human toll of 100 or more was most likely an exaggeration and that the more likely total was 28–31 victims. This reduced total was based on their review of Colonel Patterson's original journal, courtesy of Alan Patterson (grandson of the Colonel, the Bodleian Library at Oxford University and Colonel Patterson's original publication (1907)).[7] This 2001 study systematically reviewed causes of man-eating behaviour among lions with particular attention to the Man-Eaters of Tsavo.

Possible causes of "man-eating" behaviour

Theories for the man-eating behaviour of lions have been reviewed by Kerbis Peterhans and Gnoske (2001) and Bruce D. Patterson (2004). Their discussions include the following:

- An outbreak of rinderpest (cattle plague) in 1898 devastated the lions' usual prey, forcing them to find alternative food sources.

- The Tsavo lions may have been accustomed to finding dead humans at the Tsavo River crossing. Slave caravans bound for Zanzibar routinely crossed the river there.

- "Ritual invitation", or abbreviated cremation of Hindu railroad workers, invited scavenging by the lions.

An alternative argument indicates that the first lion had a severely damaged tooth that would have compromised its ability to kill natural prey. Evidence for this is presented in a series of peer-reviewed papers by Neiburger and Patterson (2000, 2001, 2002) and in Bruce D. Patterson's (2004) book.[8] This theory has been generally disregarded by the general public and Colonel Patterson, who killed the lions, personally disclaimed it, saying that he damaged that tooth with his rifle while the lion charged him one night, prompting it to flee.[9]

Studies indicate the lions ate humans as a supplement to other food, not as a last resort. Eating humans was probably an alternative to hunting or scavenging caused by dental disease and/or a limited number of prey.[10][11]

In a recent study carried out by the team of Doctor Bruce Patterson, it has been found that one of the lions had an infection at the root of his canine tooth, having made it hard for the lion to hunt. Lions normally use their jaws to grab prey like zebras and wildebeests and suffocate them.[12]

Popular culture

In film

Patterson's book was the basis for several movies:

- Men Against the Sun (1952)

- Bwana Devil (1952)

- Killers of Kilimanjaro (1956)

- The Ghost and the Darkness a 1996 film in which Val Kilmer plays John Henry Patterson

- Prey (2007)

- Mrugaraju (2001)

The incidents were also used in Killers of Kilimanjaro (1959).

In games

- The lions appear as a difficulty to be overcome in the "Cape to Cairo" scenario of the video game Railroad Tycoon II.

- Tsavo'ka (translation: Ghost in the Darkness) is a rare tiger that can be found on the Timeless Isle in World of Warcraft.

- In Cabela's Dangerous Hunts 2011 the lions were mentioned by the character Mbeki to the main character Cole as he was telling him about mysterious animals that have been terrorizing local villages.

In print

- Ghosts of Tsavo: Stalking the Mystery Lions of East Africa (2002) by Philip Caputo[13]

- The Lions of Tsavo: Exploring the Legacy of Africa's Notorious Man-Eaters (2004)[14] by Field Museum of Natural History scientist Bruce D. Patterson[15]

- The plot of the Willard Price book Lion Adventure (1967) was inspired by the man-eaters of Tsavo, wherein Hal and Roger Hunt are hired to deal with a man-eating lion that's preying on railroad workers. At one point in the book, Hal recounts Colonel Patterson's original tale.

- The story of Patterson and the man-eating lions was also an inspiration for the book Three Weeks in December (2012) by Audrey Schulman.[16]

See also

References

- ↑ Patterson, Bruce D. (2004). The Lions of Tsavo: Exploring the Legacy of Africa's Notorious Man-Eaters. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-136333-5.

- ↑ "Field Museum uncovers evidence behind man-eating; revises legend of its infamous man-eating lions" (Press release). The FIeld Museum. January 14, 2003.

- 1 2 chapter IX The Death of the Second Man-Eater, The Man-Eaters of Tsavo and other East African Adventures by Lieut.-Col. J. H. Patterson, DSO publication date unknown as recorded on Amazon Kindle

- ↑ Yeakel, J. D.; Patterson, B. D.; Fox-Dobbs, K.; Okumura, M. M.; Cerling, T. E.; Moore, J. W.; Koch, P. L.; Dominy, N. J. (2009). "Cooperation and individuality among man-eating lions". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 106 (45): 19040–3. PMC 2776458

. PMID 19884504. doi:10.1073/pnas.0905309106.

. PMID 19884504. doi:10.1073/pnas.0905309106. - ↑ Janssen, Kim (2 November 2009). "Scientists restate Tsavo lions' taste for human flesh". Chicago Tribune.

- ↑ Krueger, Harold W.; Sullivan, Charles H. (1984). "Models for Carbon Isotope Fractionation Between Diet and Bone". Stable Isotopes in Nutrition. ACS Symposium Series. 258. p. 205. ISBN 0-8412-0855-7. doi:10.1021/bk-1984-0258.ch014.

- ↑ Caputo, Philip. Ghosts of Tsavo. p. 274. ISBN 0-7922-6362-6.

- ↑ Field Museum

- ↑ "The Tsavo Man-Eaters". lionlamb.us.

- ↑ "Why Man-Eating Lions Prey on People—New Evidence". 2017-04-19. Retrieved 2017-04-19.

- ↑ DeSantis, Larisa R. G.; Patterson, Bruce D. (2017-04-19). "Dietary behaviour of man-eating lions as revealed by dental microwear textures". Scientific Reports. 7 (1). ISSN 2045-2322. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-00948-5.

- ↑ https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-017-00948-5

- ↑ Philip Caputo (June 1, 2003). Ghosts of Tsavo: Stalking the Mystery Lions of East Africa (First ed.). National Geographic. ISBN 0792241002.

- ↑ Bruce Patterson (January 22, 2004). The Lions of Tsavo: Exploring the Legacy of Africa's Notorious Man-Eaters (1 ed.). McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0071363335.

- ↑ "Field Museum Scientist Bruce Patterson's Tsavo Lions Research Highlighted in Emirates Airline's 'Open Skies'". Field Museum website's About Us page. Archived from the original on 2013-11-10.

- ↑ Schulman, Audrey (2012). Three Weeks in December. New York: Europa Editions. p. 352. ISBN 978-1-60945-064-9.

Further reading

- "Field Museum uncovers evidence behind man-eating; revises legend of its infamous man-eating lions" (Press release). The FIeld Museum. January 14, 2003.*Neiburger, E.J.; Patterson, B.D. (2000). "Man eating lions…a dental link". Journal of the American Association of Forensic Dentists. 24 (7–9): 1–3.

- Neiburger, EJ; Patterson, BD (2000). "The man-eaters with bad teeth". The New York state dental journal. 66 (10): 26–9. PMID 11199522.

- Kerbis Peterhans, J.C.; Gnoske, T.P. (2001). "The science of 'Man-eating' among lions (Panthera leo) with a reconstruction of the natural history of the "Man-eaters of Tsavo". Journal of East African Natural History. 90: 1–40. doi:10.2982/0012-8317(2001)90[1:tsomal]2.0.co;2.

- Patterson, Bruce D.; Neiburger, Ellis J.; Kasiki, Samuel M. (2003). "Tooth Breakage and Dental Disease As Causes of Carnivore–Human Conflicts". Journal of Mammalogy. 84: 190–6. doi:10.1644/1545-1542(2003)084<0190:TBADDA>2.0.CO;2.

- Patterson, B.D. 2004. The lions of Tsavo: exploring the legacy of Africa’s notorious man-eaters. McGraw-Hill, New York, 231 pp.

- Patterson, B.D.; Kasiki, S.M.; Selempo, E.; Kays, R.W. (2004). "Livestock predation by lions (Panthera leo) and other carnivores on ranches neighbouring Tsavo National Parks, Kenya". Biological Conservation. 119 (4): 507–516. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2004.01.013.

- Patterson, B.D. (2005). "Living with lions in Tsavo, or notes on managing man-eaters". Travel News & Lifestyle (East Africa). 129: 28–31.

- Dubach, Jean; Patterson, B. D.; Briggs, M. B.; Venzke, K.; Flamand, J.; Stander, P.; Scheepers, L.; Kays, R. W. (2005). "Molecular genetic variation across the southern and eastern geographic ranges of the African lion, Panthera leo". Conservation Genetics. 6: 15–24. doi:10.1007/s10592-004-7729-6.

- Patterson, B. D.; Kays, R. W.; Kasiki, S. M.; Sebestyen, V. M. (2006). "Developmental Effects of Climate on the Lion's Mane (Panthera Leo)". Journal of Mammalogy. 87 (2): 193–200. doi:10.1644/05-MAMM-A-226R2.1.

- Gnoske, T. P.; Celesia, G. G.; Kerbis Peterhans, J. C. (2006). "Dissociation between mane development and sexual maturity in lions (Panthera leo): Solution to the Tsavo riddle?". Journal of Zoology. 270 (4): 551–60. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2006.00200.x.

- Peterhans, Julian C. Kerbis; Kusimba, Chapurukha M.; Gnoske, Thomas P.; Andanje, Samuel; Patterson, Bruce D. (1998). "Man-Eaters of Tsavo: Scientific detectives take up the search for an infamous 'lions' den,' lost for one hundred years". Natural History. 107 (9): 12–4.

- Patterson, B.D. 2004. The lions of Tsavo: exploring the legacy of Africa’s notorious man-eaters. McGraw-Hill, New York, 231 pp.

Sources

External links

- Chicago Field Museum – Tsavo Lion Exhibit

- Journal: man-eaters of Tsavo – Natural History, Nov. 1998 (via FindArticles.com)

- Man-Eating Lions Not Aberrant, Experts Say – National Geographic News, 4 Jan 2004