Breeches role

| Cross-dressing |

|---|

| History of cross-dressing |

| Key elements |

| Modern drag culture |

| Sexual aspects |

|

Sexual attraction to cross-dressers |

| Other aspects |

| Passing as male |

| Passing as female |

| Organizations |

| Books |

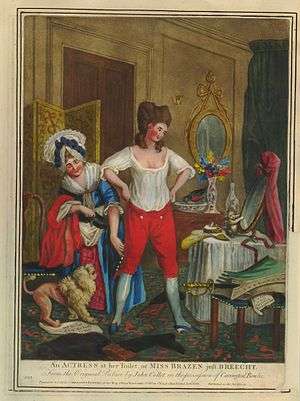

A breeches role (also pants role or trouser role, travesti or "Hosenrolle") is a role in which an actress appears in male clothing. Breeches (/ˈbrɪtʃᵻz/, also "britches"), tight-fitting knee-length pants, were the standard male garment at the time breeches roles were introduced.

In opera it also refers to any male character that is sung and acted by a female singer. Most often the character is an adolescent or a very young man, sung by a mezzo-soprano or contralto.[1] The operatic concept assumes that the character is male, and the audience accepts him as such, even knowing that the actor is not. Cross-dressing female characters (e.g., Leonore in Fidelio or Gilda in Act III of Rigoletto) are not considered breeches roles. The most frequently performed breeches roles are Cherubino (The Marriage of Figaro), Octavian (Der Rosenkavalier), Hansel (Hansel and Gretel) and Orpheus (Orpheus and Euridice), though the latter was originally written for a male singer, first a castrato and later, in the revised French version, an haute-contre.

Because non-musical stage plays generally have no requirements for vocal range, they do not usually contain breeches roles in the same sense as opera. Some plays do have male roles that were written for adult female actors, and (for other practical reasons) are usually played by women (e.g., Peter Pan); these could be considered modern-era breeches roles. However, in most cases, the choice of a female actor to play a male character is made at the production level; Hamlet is not a breeches role, but Sarah Bernhardt once played Hamlet as a breeches role. When a play is spoken of as "containing" a breeches role, this does mean a role where a female character pretends to be a man and uses male clothing as a disguise.

History

When the London theatres re-opened in 1660, the first professional actresses appeared on the public stage, replacing the boys in dresses of the Shakespeare era. To see real women speak the risqué dialogue of Restoration comedy and show off their bodies on stage was a great novelty, and soon the even greater sensation was introduced of women wearing male clothes on stage. Out of some 375 plays produced on the London stage between 1660 and 1700, it has been calculated that 89, nearly a quarter, contained one or more roles for actresses in male clothes (see Howe). Practically every Restoration actress appeared in trousers at some time, and breeches roles would even be inserted gratuitously in revivals of older plays.

Some critics, such as Jacqueline Pearson, have argued that these cross-dressing roles subvert conventional gender roles by allowing women to imitate the roistering and sexually aggressive behaviour of male Restoration rakes, but Elizabeth Howe has objected in a detailed study that the male disguise was "little more than yet another means of displaying the actress as a sexual object". The epilogue to Thomas Southerne's Sir Anthony Love (1690) suggests that it does not much matter if the play is dull, as long as the audience can glimpse the legs of the famous "breeches" actress Susanna Mountfort (also known as Susanna Verbruggen):

- You'l' hear with Patience a dull Scene, to see,

- In a contented lazy waggery,

- The Female Mountford bare above the knee.

Katharine Eisaman Maus also argues that as well as revealing the female legs and buttocks, the breeches role frequently contained a revelation scene where the character not only unpins her hair but as often reveals a breast as well. This is evidenced in the portraits of many of these actresses of the Restoration.

Breeches roles remained an attraction on the British stage for centuries, but their fascination gradually declined as the difference in real-life male and female clothing became less extreme. They played a part in Victorian burlesque and are traditional for the principal boy in pantomime.

Opera

Historically, the list of roles that are considered to be breeches roles is constantly changing, depending on the tastes of the opera-going public. In early Italian opera, many leading operatic roles were assigned to a castrato, a male castrated before puberty with a very strong and high voice. As the practice of castrating boy singers faded, composers created heroic male roles in the mezzo-soprano range, where singers such as Marietta Alboni and Rosamunda Pisaroni specialised in such roles.[1] (See Xerxes below.)

Currently, many castrato roles are being reclaimed by men. As the training and use of countertenors becomes more common, there are more men with these very high voices to sing these roles.

Casting directors are left with choices such as whether to cast the young Prince Orlofsky in Die Fledermaus for a woman or man; both commonly sing the role. When played by a mezzo, the prince looks like a woman, but sounds like a boy. When played by a counter-tenor, he looks like a man, but sings like a woman. This disparity is made even clearer if, as in this case, there is also spoken dialogue.

The term Travesty (from the Italian travesti, disguised) applies to any roles sung by the opposite sex.[2]

A closely related term is a skirt role, a female character to be played by a male singer, usually for comic or visual effect. These roles are often ugly stepsisters or very old women, and are not as common as trouser roles. As women were not allowed to sing on stage in the Papal States during the Baroque period, many female operatic roles which premiered in those areas were originally written as skirt roles for castrati (e.g. Mandane and Semira in Leonardo Vinci's Artaserse). Britten's Madwoman in Curlew River and the Cook in Prokofiev's The Love for Three Oranges are examples. The role of the witch in Humperdinck's Hänsel und Gretel, although written for a mezzo-soprano is now more regularly sung by a tenor, who sings the part an octave lower. In the same opera the "male" roles of Hänsel, the Sandman, and the Dewman are however meant to be sung by women.

Operas with breeches roles include:

- Adès's The Tempest: "Ariel" is sung by a soprano

- Arne's Artaxerxes: "Arbaces" is sung by a mezzo-soprano

- Adamo's Little Women: "Friedrich Bhaer" may be sung by a mezzo-soprano.

- Bellini's I Capuleti e i Montecchi: "Romeo" is sung by a mezzo-soprano

- Berlioz's Benvenuto Cellini: "Ascanio" is sung by a mezzo-soprano

- Catalani's La Wally: "Walter" is sung by a soprano

- Chabrier's L'étoile: "Lazuli" the peddler is sung by a soprano

- Chabrier's Une éducation manquée: "Gontran de Boismassif" is sung by a soprano

- Charpentier's David et Jonathas: "Jonathas" is sung by a soprano; La Pythonisse is sung by a haute-contre, which is a high-pitched male voice, similar to a Countertenor.

- Corigliano's "The Ghosts of Versailles": "Cherubino" (a recreation of the same character from Le nozze di Figaro) is sung by a mezzo-soprano

- Donizetti's Alahor in Granata: "Muley-Hassem" is sung by a contralto

- Donizetti's Anna Bolena: "Smeton" is sung by a mezzo-soprano

- Donizetti's Lucrezia Borgia: "Maffio Orsini" is sung by a contralto

- Dvořák's Rusalka: "The Kitchen Boy" is sung by a soprano

- Glinka's A Life for the Tsar: "Vanya" is sung by a contralto

- Glinka's Ruslan and Lyudmila: "Ratmir" is sung by a contralto

- Gluck's Orfeo ed Euridice: Originally written for a castrato, "Orfeo" is sung by a mezzo-soprano, contralto or counter-tenor

- Gounod's Faust: "Siebel" is sung by a contralto, a mezzo-soprano or a soprano

- Gounod's Romeo and Juliet: "Stefano" is sung by a soprano

- Hahn's Mozart: The title is sung by a soprano

- Händel's Alcina: "Ruggiero" is sung by a mezzo-soprano

- Händel's Ariodante: The role of "Ariodante" was premiered by a soprano-castrato and is performed today by a mezzo-soprano; "Lurcanio" was originally written for contralto, but later rewritten by Handel for tenor.[3] In modern performances it is generally left to the director to decide whether to use contralto (or countertenor) or a lyric tenor.

- Händel's Giulio Cesare: "Julius Caesar" was originally written for an alto-castrato and is today sung by a mezzo-soprano or countertenor; "Sesto" is sung by a soprano

- Händel's Xerxes: the title role "Xerxes", sung at its premiere by a castrato, is currently sung by a mezzo-soprano or a countertenor

- Haydn's La canterina: The role of "Don Ettore" is sung by a soprano

- Lecocq's Le petit duc: the title role is sung by a soprano

- Humperdinck's Hänsel und Gretel: "Hänsel" is sung by a mezzo-soprano; The Sand-Man and The Dew-Man sung by sopranos; The Witch often sung by a tenor

- Janáček's From the House of the Dead: Aljeja, a young Tartar is sung by a mezzo-soprano

- Massenet's Cendrillon: the role of "Le Prince Charmant" was written for a soprano (in some performances the role is taken by a tenor)

- Massenet's Chérubin: The title role is sung by a soprano

- Meyerbeer's Les Huguenots : "Urbain" the page is sung by a mezzo-soprano

- Monteverdi's L'incoronazione di Poppea: "Nero" is sung by a soprano (today the role is often sung by a male tenor or contratenor)

- Mozart's Le nozze di Figaro: "Cherubino" is sung by a mezzo-soprano

- Mozart's La clemenza di Tito : "Sesto" and "Annio" are sung by sopranos

- Mozart's Idomeneo: "Idamante" is sung by a mezzo-soprano

- Mozart's Il re pastore: "Amintas" was originally written for soprano-castrato, and in modern performances is sung by a lyric soprano

- Mozart's Mitridate, re di Ponto: "Farnace" is sung by a mezzo-soprano or contralto, and "Sifare" is sung by a soprano. However, "Farnace" is commonly done by a countertenor.

- Mozart's La finta giardiniera: "Ramiro" is sung by a mezzo-soprano

- Offenbach's Mesdames de la Halle: Croûte-au-pot (the kitchen boy) is sung by a soprano; Madame Poiretapée, Madame Madou, and Madame Beurrefondu are sung by a tenor and two baritones

- Offenbach's Geneviève de Brabant: "Drogan" the young baker is sung by a soprano

- Offenbach's Daphnis et Chloé: "Daphnis" is sung by a mezzo-soprano

- Offenbach's Le pont des soupirs: The page "Amoroso" is sung by a mezzo-soprano

- Offenbach's Les bavards: The young poet "Roland" is sung by a contralto

- Offenbach's La belle Hélène: "Oreste" is sung by a mezzo-soprano

- Offenbach's Robinson Crusoé: "Friday" is sung by a mezzo-soprano

- Offenbach's Les brigands: The farmer "Fragoletto" is sung by a mezzo-soprano

- Offenbach's La jolie parfumeuse: The young clerk "Bavolet" is sung by a soprano

- Offenbach's Madame l'archiduc: "Fortunato, captain of the archduke's dragoons" is sung by a mezzo-soprano

- Offenbach's Le voyage dans la lune: "Prince Caprice" is sung by a mezzo-soprano

- Offenbach's The Tales of Hoffmann: "Nicklausse" is sung by a mezzo-soprano

- Offenbach's Orphée aux enfers: "Cupidon" (Cupid) is sung by a soprano

- Pfitzner's Palestrina: Ighino is sung by a soprano; Silla by a mezzo-sporano

- Ravel's L'enfant et les sortilèges: the title role of The Boy is written for a mezzo-soprano; The Shepherd is sung by a mezzo-soprano

- Rossini's Tancredi: "Tancredi" and "Roggiero" are sung by mezzo-sopranos or contraltos

- Rossini's Bianca e Falliero: "Falliero" is sung by a mezzo-soprano

- Rossini's La donna del lago: "Malcolm" is sung by a contralto

- Rossini's Le comte Ory : "Isolier" is sung by a mezzo-soprano

- Rossini's Semiramide: "Arsace" is sung by a mezzo-soprano

- Rossini's Otello: the title role was written for a tenor, but also was sung by mezzo-soprano Maria Malibran

- Rossini's Guillaume Tell: Tell's son Jemmy is sung by a soprano

- Gil Shohat's The Child Dreams: "The Child" is sung by a soprano; "The Crippled Youth" (i.e. The Poet) by a mezzo-soprano

- Johann Strauss II's Die Fledermaus: "Prince Orlofsky" is sung by a mezzo-soprano (almost always)

- Richard Strauss's Salome: "The Page of Herodias" is sung by a contralto

- Richard Strauss's Ariadne auf Naxos: "The Composer" is sung by a mezzo-soprano

- Richard Strauss's Der Rosenkavalier: "Octavian" is sung by a mezzo-soprano

- Verdi's Un ballo in maschera: "Oscar", Gustavus III's page, is sung by a soprano

- Verdi's 'Don Carlos: The page Thibault (Tebaldo) is sung by a soprano

- Wagner's Rienzi: "Adriano" is sung by a mezzo-soprano

- Wagner's Tannhäuser: The Young Shepherd is sung by a soprano

- Wagner's Parsifal: Two novices in the all-male society of Knights of the Grail are sung by sopranos

- Wagner's Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg: Several apprentices are sung by women

See also

Footnotes

References

- Howe, Elizabeth (1992). The First English Actresses: Women and Drama 1660–1700. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Maus, Katharine Eisaman (1979). "'Playhouse Flesh and Blood': Sexual Ideology and the Restoration Actress". New York: Harcourt Brace Anthology of Drama (1996).

- Pearson, Jacqueline (1988). The Prostituted Muse: Images of Women and Women Dramatists 1642–1737. New York: St. Martin's Press.