2017 Atlantic hurricane season

| 2017 Atlantic hurricane season | |

|---|---|

|

Season summary map | |

| Seasonal boundaries | |

| First system formed | April 19, 2017 |

| Last system dissipated | Season ongoing |

| Strongest storm | |

| Name | Franklin |

| • Maximum winds |

85 mph (140 km/h) (1-minute sustained) |

| • Lowest pressure | 981 mbar (hPa; 28.97 inHg) |

| Seasonal statistics | |

| Total depressions | 7 |

| Total storms | 6 |

| Hurricanes | 1 |

| Major hurricanes (Cat. 3+) | 0 |

| Total fatalities | 5 total |

| Total damage | ≥ $3.1 million (2017 USD) |

| Related articles | |

The 2017 Atlantic hurricane season is an ongoing event in the annual formation of tropical cyclones in the Atlantic basin. The season officially began on June 1, and will end on November 30, 2017. These dates historically describe the period of year when most tropical cyclones form in the Atlantic basin and are adopted by convention. However, as shown by Tropical Storm Arlene in April, the formation of tropical cyclones is possible at any time of the year.

For the third consecutive year activity began early, with the formation of Tropical Storm Arlene on April 19, nearly a month and a half before the official start of the season. It is only the second named storm on record to exist in the month in April, with the first being Ana in 2003, as well as the strongest overall for the month of April. In mid-June, Tropical Storm Bret struck the island of Trinidad, which is rarely impacted by tropical cyclones due to its low latitude. Tropical Storm Cindy struck the state of Louisiana a few days later, becoming the first tropical cyclone to strike the state since Hurricane Isaac in 2012.

Beginning this year, the National Hurricane Center has the option to issue advisories, and thus allow watches and warnings to be issued, on disturbances that are not yet tropical cyclones but have a high chance to become one, and are expected to bring tropical storm or hurricane conditions to landmasses within 48 hours. Such systems are termed "potential tropical cyclones". Advisories on these storms contain the same content, including track forecasts and cyclone watches and warnings, as advisories on active tropical cyclones.[1] This was first demonstrated on June 18 with the designation of Potential Tropical Cyclone Two—which later developed into Tropical Storm Bret—east-southeast of the Windward Islands.[2]

Seasonal forecasts

| Source | Date | Named storms |

Hurricanes | Major hurricanes | |

| Average (1981–2010[3]) | 12.1 | 6.4 | 2.7 | ||

| Record high activity | 28 | 15 | 7 | ||

| Record low activity | 4 | 2† | 0† | ||

| ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– | |||||

| TSR[4] | December 13, 2016 | 14 | 6 | 3 | |

| TSR[5] | April 5, 2017 | 11 | 4 | 2 | |

| CSU[6] | April 6, 2017 | 11 | 4 | 2 | |

| TWC[7] | April 17, 2017 | 12 | 6 | 2 | |

| NCSU[8] | April 18, 2017 | 11–15 | 4–6 | 1–3 | |

| TWC[9] | May 20, 2017 | 14 | 7 | 3 | |

| NOAA[10] | May 25, 2017 | 11–17 | 5–9 | 2–4 | |

| TSR[11] | May 26, 2017 | 14 | 6 | 3 | |

| CSU[12] | June 1, 2017 | 14 | 6 | 2 | |

| UKMO[13] | June 1, 2017 | 13* | 8* | N/A | |

| TSR[14] | July 4, 2017 | 17 | 7 | 3 | |

| CSU[15] | July 5, 2017 | 15 | 8 | 3 | |

| CSU[16] | August 4, 2017 | 16 | 8 | 3 | |

| TSR[17] | August 4, 2017 | 17 | 7 | 3 | |

| NOAA[18] | August 9, 2017 | 14–19 | 5–9 | 2–5 | |

| ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– | |||||

| Actual activity |

6 | 1 | 0 | ||

| * June–November only. † Most recent of several such occurrences. (See all) | |||||

Ahead of and during the season, several national meteorological services and scientific agencies forecast how many named storms, hurricanes and major (Category 3 or higher on the Saffir–Simpson scale) hurricanes will form during a season and/or how many tropical cyclones will affect a particular country. These agencies include the Tropical Storm Risk (TSR) Consortium of the University College London, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and Colorado State University (CSU). The forecasts include weekly and monthly changes in significant factors that help determine the number of tropical storms, hurricanes, and major hurricanes within a particular year.[4] Some of these forecasts also take into consideration what happened in previous seasons and the dissipation of the 2014–16 El Niño event. On average, an Atlantic hurricane season between 1981 and 2010 contained twelve tropical storms, six hurricanes, and two major hurricanes, with an Accumulated Cyclone Energy (ACE) index of between 66 and 103 units.[3]

Pre-season outlooks

The first forecast for the year was issued by TSR on December 13, 2016.[4] They anticipated that the 2017 season would be a near-average season, with a prediction of 14 named storms, 6 hurricanes, and 3 major hurricanes. They also predicted an ACE index of around 101 units.[4] On December 14, CSU released a qualitative discussion detailing five possible scenarios for the 2017 season, taking into account the state of the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation and the possibility of El Niño developing during the season.[19] TSR lowered their forecast numbers on April 5, 2017 to 11 named storms, 4 hurricanes, and 2 major hurricanes, based on recent trends favoring the development of El Niño.[5] The next day, CSU released their prediction, also predicting a total of 11 named storms, 4 hurricanes, and 2 major hurricanes.[6] On April 17, The Weather Company released their forecasts, calling for 2017 to be a near-average season, with a total of 12 named storms, 6 hurricanes, and 2 major hurricanes.[7] The next day, on April 18, North Carolina State University released their prediction, also predicting a near-average season, with a total of 11–15 named storms, 4–6 hurricanes, and 1–3 major hurricanes.[8] On May 20, The Weather Company issued an updated forecast, raising their numbers to 14 named storms, 7 hurricanes, and 3 major hurricanes to account for Tropical Storm Arlene as well as the decreasing chance of El Niño forming during the season.[9] On May 25, NOAA released their prediction, citing a 70% chance of an above average season due to "a weak or nonexistent El Niño", calling for 11–17 named storms, 5–9 hurricanes, and 2–4 major hurricanes.[10] On May 26, TSR updated its prediction to around the same numbers as its December 2016 prediction, with only a minor change in the expected ACE index amount to 98 units.[11]

Mid-season outlooks

CSU updated their forecast on June 1 to include 14 named storms, 6 hurricanes and 2 major hurricanes to include Tropical Storm Arlene.[12] It was based on the current status of the North Atlantic Oscillation, which was showing signs of leaning towards a negative phase, favoring a warmer tropical Atlantic; and the chances of El Niño forming were significantly lower. However, they stressed on the uncertainty that the El Niño–Southern Oscillation could be in a warm-neutral phase or weak El Niño conditions by the peak of the season.[12] On the same day, the United Kingdom Met Office (UKMO) released its forecast of a very slightly above-average season. It predicted 13 named storms with a 70% chance that the number would be in the range 10 to 16 and 8 hurricanes with a 70% chance that the number would be in the range 6 to 10. It also predicted an ACE index of 145 with a 70% chance that the index would be between 92 and 198.[13] On July 4, TSR released their fourth forecast for the season, increasing their predicted numbers to 17 named storms, 7 hurricanes, and 3 major hurricanes, due to the fact that El Niño conditions would no longer develop by the peak of the season and the warming of sea-surface temperatures across the basin. Additionally, they predicted a revised ACE index of 116 units.[14] During August 9, NOAA released their final outlook for the season, raising their predictions to 14-19 named storms, though retaining 5-9 hurricanes and 2-5 major hurricanes. They also stated that the season has the potential to be extremely active, possibly the most active since 2010.[18]

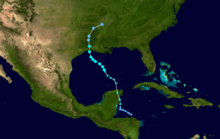

Seasonal summary

The Atlantic hurricane season officially began on June 1, 2017, although activity began earlier for the third consecutive year, the first being 2015. Roughly a month or so before the official start, the first storm, Arlene, developed on April 19 in the northern Atlantic Ocean. It was the first named storm to develop in the month of April since Ana in 2003. Activity quieted down during May and for the first half of June. Shortly afterwards, by June 20, two more storms had developed; the first was Bret, which was an unusual and rare storm that affected areas in the southeastern Caribbean Sea, including Trinidad and Tobago. The second, Cindy, formed in the Gulf of Mexico less than a day after Bret had developed, the first such occurrence on record. In early July, a tropical depression developed in the Main Development Region (MDR), the second tropical cyclone to develop in the MDR before the month of August; the previous was Bret. Ten days elapsed before the development of the next named storm, Don, on July 17. In late July, a cold front was stalled over the Gulf of Mexico and portions of the southeastern United States, which is typically rare on such occassion. On July 31, The front later became Tropical Depression Six, forming just south off the Florida Panhandle. Within just two hours, the depression later transtioned into Tropical Storm Emily. About a week later, Tropical Storm Franklin formed, later becoming the first hurricane of the season in the Bay of Campeche.

The accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) index for the 2017 Atlantic hurricane season, as of 03:00 UTC on August 10, is 6.985 units.[nb 1] With an ACE value under 4 units following the dissipation of Emily, 2017 set the record for lowest ACE produced by a season's first five named storms.[20]

Systems

Tropical Storm Arlene

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | April 19 – April 21 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min) 990 mbar (hPa) |

An extratropical cyclone formed along a cold front well to the southeast of Newfoundland on April 15, producing waves as high as 40 feet (12 m) over subsequent days.[21] The system initially failed to organize appreciably; by April 17, however, sporadic convection began to coalesce around an increasingly well defined circulation. This process continued with the formation of a curved banding feature near the center on April 19, prompting the National Hurricane Center (NHC) to upgrade the low to Subtropical Depression One at 15:00 UTC that day.[22] At this time, the system was situated 890 mi (1,435 km) southwest of the Azores.[23] Little change in strength occurred throughout the day.[24]

Convection became more concentrated and the system's wind field contracted during the early morning hours of April 20, and the system transitioned to a fully tropical cyclone at 15:00 UTC that day.[25] Six hours later, despite forecasts predicting it would dissipate, the storm unexpectedly strengthened into Tropical Storm Arlene.[26] Revolving around a low to its west, Arlene defied forecasts again and attained a peak intensity of 50 mph (85 km/h) at 03:00 UTC on April 21, despite a deteriorating satellite presentation.[27] Twelve hours later, however, Arlene became embedded within the aforementioned larger extratropical cyclone, and lost its identity as a tropical cyclone.[28] Arlene's remnants continued to persist through the next day, executing a counterclockwise loop around the larger extratropical cyclone, while in the process of merging with it.[29] Early on April 23, the remnants of Arlene fully merged into the larger extratropical system.[30]

Upon its formation as a subtropical depression on April 19, Arlene was the sixth known subtropical or tropical cyclone to form in the month of April in the Atlantic basin; the other instances were Ana in 2003, a subtropical storm in April 1992, and three tropical depressions in 1912, 1915, and 1973, respectively. When Arlene became a tropical storm on April 20, this marked only the second such occurrence on record, after Ana in 2003.[31][nb 2] Furthermore, it had the lowest central pressure of any Atlantic storm recorded in the month of April, with a central pressure of 990 mbar (hPa; 29.23 inHg), again surpassing Ana.[32] [33]Additionally, unrelated to Arlene, Tropical Storm Adrian in the Eastern Pacific basin also formed before the corresponding hurricane season was set to officially begin, being the earliest named storm in the Eastern Pacific proper. The last time where the first storms in both basins were pre-season storms was in 2012.[34]

Tropical Storm Bret

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | June 19 – June 20 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 45 mph (75 km/h) (1-min) 1007 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave moved off the coast of Africa on June 13 and was first monitored by the National Hurricane Center shortly afterwards.[35] Development, however, was expected to be slow due to its low latitude and relatively fast motion. As it moved swiftly across the Main Development Region of the Atlantic Ocean, the disturbance began to gradually organize, and the NHC raised development chances slightly on June 16.[36] Little change in organization occurred until June 18, at which point a burst of convection near the center of the disturbance prompted the NHC to designate the system as Potential Tropical Cyclone Two at 21:00 UTC. This was the agency's first designation of a disturbance that had not yet developed into a tropical cyclone.[37] The storm continued to organize as it accelerated towards Venezuela and Trinidad and Tobago throughout the night, with banding features becoming evident. Later on June 19, the system developed a closed low-level circulation and was upgraded to Tropical Storm Bret at 21:00 UTC.[38] One day later, at 21:00 UTC on June 20, the last advisory on Bret was issued following its degeneration into a tropical wave.[39]

According to Phil Klotzbach of Colorado State University, Bret was the earliest storm to form in the Main Development Region on record, surpassing a record set by Tropical Storm Ana in 1979.[40] Bret was also the lowest latitude named storm in the month of June since 1933 at 9.4°N.[41] In Trinidad, one person died after he slipped and fell while running across a makeshift bridge; the fatality is considered indirectly related to Bret.[42][43] Another fatality occurred in Tobago after a man's house collapsed on him; he eventually succumbed to his injuries a week later.[44]

Tropical Storm Cindy

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | June 20 – June 23 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min) 992 mbar (hPa) |

The NHC first began monitoring the potential for tropical cyclone formation over the northwestern Caribbean Sea on June 13.[45] A large area of disturbed weather developed within the region three days later,[46] and it slowly organized while entering the central Gulf of Mexico, prompting the NHC to begin advisories on a potential tropical cyclone on June 19. The structure of the system was initially sprawling, with tropical storm-force winds well displaced from a broad area of low pressure with embedded swirls.[47] A reconnaissance aircraft investigating the system around 18:00 UTC the following day was able to pinpoint a well-defined center, indicating the formation of Tropical Storm Cindy.[48] Despite the presence of dry air and strong wind shear, the cyclone still managed to attain peak winds of 60 mph (95 km/h) before weakening on approach to the Louisiana coastline.[49] It made landfall between Port Arthur, Texas and Cameron, Louisiana early on June 22 and weakened while progressing inland.[50]

A state of emergency was declared for Biloxi, Mississippi in anticipation of flooding. A ten-year-old boy died from injuries sustained during the storm in Fort Morgan, Alabama.[51] A second fatality later occurred in Bolivar Peninsula, Texas.[52]

Tropical Depression Four

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | July 6 – July 7 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 30 mph (45 km/h) (1-min) 1008 mbar (hPa) |

Early on June 29, the NHC began tracking a tropical wave embedded within a large envelope of deep moisture across the coastline of western Africa.[53] The disturbance was introduced as a potential contender for tropical cyclone formation two days later, as environmental conditions were expected to favor slow organization.[54] It began to show signs of organization over the central Atlantic early on July 3,[55] but the chances for development began to decrease two days later as the system moved toward a more stable environment.[56] Having already acquired a well-defined circulation, the development of a persistent mass of deep convection around 03:00 UTC the following day prompted the NHC to upgrade the wave to Tropical Depression Four, located about 1,545 miles (2,485 km) east of the Lesser Antilles.[57] Despite wind shear being low, the nascent depression struggled to intensify due to a dry environment caused by a Saharan Air Layer to its east, causing the low-level circulation to weaken, and resulting in the tropical depression degenerating into an open trough late the next day.[58]

Tropical Storm Don

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | July 17 – July 19 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min) 1007 mbar (hPa) |

Late on July 15, the NHC highlighted a low-pressure trough over the central Atlantic as having the potential to develop into a tropical cyclone in the coming days.[59] The disturbance began to show signs of organization early on July 17,[60] and data from a reconnaissance aircraft investigating the system confirmed the development of Tropical Storm Don around 21:00 UTC that day.[61] The storm's overall appearance improved over subsequent hours up until around 09:00 UTC, as a central dense overcast, accompanied by significant clusters of lightning, became pronounced.[62] Don attained its peak intensity at this time, characterised by winds of approximately 50 mph (85 km/h).[62] The next plane to investigate the cyclone a few hours later, however, found that the system's center had become less defined, and that sustained wind speeds had decreased to about 40 mph (65 km/h).[63] A combination of reconnaissance data and surface observations from the Windward Islands indicated that Don opened up into a tropical wave around 03:00 UTC on July 19 as it entered the eastern Caribbean Sea.[64]

Tropical Storm Emily

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | July 31 – August 2 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 45 mph (75 km/h) (1-min) 1005 mbar (hPa) |

In late July, a dissipating cold front extended into the northeastern Gulf of Mexico, where the NHC began forecasting the development of an area of low pressure over the next day on July 30. Any development was expected to be slow due to land proximity and marginal upper-level winds.[65] Contrary to predictions, a rapid period of organization occurred over the next 24 hours and the system was deemed as Tropical Depression Six at 09:00 UTC on July 31,[66] strengthening into Tropical Storm Emily just two hours later. After attaining its peak intensity with winds of 45 mph (75 km/h) and a minimum pressure of 1,005 mbar (29.7 inHg),[67] Emily made landfall on Anna Maria Island around 14:45 UTC. Weakening quickly ensued, and later that day the circulation of Emily became elongated as it was downgraded to a tropical depression.[68] The increasingly disrupted system later moved off the First Coast of Florida into the western Atlantic early the next day, accelerating northeastwards before becoming embedded within a frontal zone early on August 2.[69]

Following the classification of Tropical Storm Emily, Florida Governor Rick Scott declared a state of emergency for 31 counties to ensure residents were provided with the necessary resources.[70] The storm spawned an EF0 tornado near Bradenton. The tornado was on the ground for about 1.3 mi (2.1 km) and destroyed two barns and a few greenhouses, while an engineered wall collapsed, leaving about $96,000 in damage.[71] On August 1, torrential rains related to Emily impacted parts of Miami Beach, with accumulations reaching 6.97 in (177 mm) in 3.5 hours, of which 2.17 in (55 mm) fell in just 30 minutes.[72] Coinciding with high tide the deluge overwhelmed flood pumps, with three of them shutting down due to lightning-induced power outages, and resulted in significant flash floods. Multiple buildings suffered water damage, with some having 2.5 ft (0.76 m) of standing water. One person was hospitalized after becoming stuck in flood waters.[73][74] Portions of Downtown Miami, such as Brickell, were also heavily affected; numerous vehicles became stranded in flooded roadways.[75]

Hurricane Franklin

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 7 – August 10 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 85 mph (140 km/h) (1-min) 981 mbar (hPa) |

The NHC began tracking a tropical wave in the southeastern Caribbean Sea for possible development on August 3.[76] After organizing for a few days, advisories were initiated on Potential Tropical Cyclone Seven at 21:00 UTC on August 6.[77] The disturbance became Tropical Storm Franklin at 03:00 UTC on August 7.[78] After strengthening into a moderate tropical storm, Franklin made its first landfall near Pulticub, Mexico at 03:00 UTC on August 8.[79] The cyclone weakened considerably while over the peninsula, however its satellite presentation remained well-defined, with the inner core tightening up considerably.[80] Later that day, Franklin emerged into the Bay of Campeche, and immediately began strengthening again.

Immediately upon classification of Franklin as a potential tropical cyclone, tropical storm warnings were issued for much of the eastern side of the Yucatan Peninsula on August 6;[77] a small portion of the coastline was upgraded to a hurricane watch with the possibility of Franklin nearing hurricane intensity as it approached the coastline the next night. Approximately 330 people were reported as going into storm shelters, and around 2,200 relocated from the islands near the coastline to farther inland in advance of the storm.[81] In the Mexican part of the peninsula, damage was reported as having being minimal, mainly in Belize as the storm tracked slightly more northwards then expected, lessening impacts.[81] Some areas received up to a foot of rain though.[82]

Hurricane Franklin made landfall near Lechuguillas, Veracruz in Mexico around 12:30 A.M. CST on August 10, 2017 as a Category 1 hurricane with winds of 85 mph. After emerging on the Pacific side of Mexico, Franklin's remnants contributed to the formation of Tropical Storm Jova in the East Pacific.[83]

Storm names

The following list of names will be used for named storms that form in the North Atlantic in 2017. Retired names, if any, will be announced by the World Meteorological Organization in the spring of 2018. The names not retired from this list will be used again in the 2023 season.[84] This is the same list used in the 2011 season, with the exception of the name Irma, which replaced Irene. The usage of the name "Don" in July garnered some negative attention relating to United States President Donald Trump. Max Mayfield, former director of the National Hurricane Center, clarified that the name had no relation to Trump and was chosen in 2006 as a replacement for Dennis. Regardless, some outlets such as the Associated Press "poked fun" at the name and Trump.[85][86]

|

|

Season effects

This is a table of all the storms that have formed in the 2017 Atlantic hurricane season. It includes their duration, names, landfall(s), denoted in parentheses, damages, and death totals. Deaths in parentheses are additional and indirect (an example of an indirect death would be a traffic accident), but were still related to that storm. Damage and deaths include totals while the storm was extratropical, a wave, or a low, and all the damage figures are in 2017 USD.

| Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale | ||||||

| TD | TS | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 |

| Storm name |

Dates active | Storm category

at peak intensity |

Max 1-min wind mph (km/h) |

Min. press. (mbar) |

Areas affected | Damage (millions USD) |

Deaths | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arlene | April 19 – 22 | Tropical storm | 50 (85) | 990 | None | None | None | |||

| Bret | June 19 – 20 | Tropical storm | 45 (75) | 1007 | Guyana, Venezuela, Trinidad and Tobago, Windward Islands | ≥3 | 1 (1) | |||

| Cindy | June 20 – 23 | Tropical storm | 60 (95) | 992 | Honduras, Belize, Yucatán Peninsula, Cuba, Southern United States, Eastern United States | Unknown | 2 (1) | |||

| Four | July 6 – 7 | Tropical depression | 30 (45) | 1008 | None | None | None | |||

| Don | July 17 – 19 | Tropical storm | 50 (85) | 1007 | Windward Islands, Barbados, Trinidad and Tobago | None | None | |||

| Emily | July 31 – August 2 | Tropical storm | 45 (75) | 1005 | Florida | 0.096 | None | |||

| Franklin | August 7 – 10 | Category 1 hurricane | 85 (140) | 981 | Nicaragua, Honduras, Guatemala, Belize, Yucatán Peninsula, Mexico | Unknown | None | |||

| Season Aggregates | ||||||||||

| 7 systems | April 19 – Season ongoing |

85 (140) | 981 | ≥3.096 | 3 (2) | |||||

See also

- List of Atlantic hurricane seasons

- 2017 Pacific hurricane season

- 2017 Pacific typhoon season

- 2017 North Indian Ocean cyclone season

- South-West Indian Ocean cyclone seasons: 2016–17, 2017–18

- Australian region cyclone seasons: 2016–17, 2017–18

- South Pacific cyclone seasons: 2016–17, 2017–18

Footnotes

- ↑ The totals represent the sum of the squares for every (sub)tropical storm's intensity of over 33 knots (38 mph, 61 km/h), divided by 10,000. Calculations are provided at Talk:2017 Atlantic hurricane season/ACE calcs.

- ↑ It should be noted that Arlene would likely not have been detected without the help of satellites, and there may well have been other similar storms this early in the year in the pre-satellite era (1966 and before).[26]

References

- ↑ "Update on National Hurricane Center Products and Services for 2017" (PDF). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved March 12, 2017.

- ↑ "Potential Tropical Cyclone Two". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Retrieved 2017-06-20.

- 1 2 "Background Information: The North Atlantic Hurricane Season". Climate Prediction Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. August 9, 2012. Retrieved December 13, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 Mark Saunders; Adam Lea (December 13, 2016). Extended Range Forecast for Atlantic Hurricane Activity in 2017 (PDF) (Report). London, United Kingdom: Tropical Storm Risk.

- 1 2 Mark Saunders; Adam Lea (April 5, 2017). April Forecast Update for Atlantic Hurricane Activity in 2017 (PDF) (Report). London, United Kingdom: Tropical Storm Risk.

- 1 2 Phillip J. Klotzbach; William M. Gray (April 6, 2017). "Extended Range Forecast of Atlantic Seasonal Hurricane Activity and Landfall Strike Probability for 2017" (PDF). Colorado State University. Retrieved April 6, 2017.

- 1 2 "2017 Atlantic Hurricane Season Forecast Calls For a Near-Average Number of Storms, Less Active Than 2016". weather.com. Retrieved 20 April 2017.

- 1 2 WRAL (18 April 2017). "NCSU researchers predict 'normal' hurricane season :: WRAL.com". wral.com. Retrieved 20 April 2017.

- 1 2 "2017 Atlantic Hurricane Season Forecast Update Calls For An Above-Average Number Of Storms". weather.com. Retrieved 20 May 2017.

- 1 2 "Above-normal Atlantic hurricane season is most likely this year". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. May 25, 2017.

- 1 2 Mark Saunders; Adam Lea (May 26, 2017). Pre-Season Forecast for North Atlantic Hurricane Activity in 2017 (PDF) (Report). London, United Kingdom: Tropical Storm Risk.

- 1 2 3 Phillip J. Klotzbach; William M. Gray (June 1, 2017). "Extended Range Forecast of Atlantic Seasonal Hurricane Activity and Landfall Strike Probability for 2017" (PDF). Colorado State University. Retrieved June 1, 2017.

- 1 2 "North Atlantic tropical storm seasonal forecast 2017". Met Office. June 1, 2017. Retrieved July 21, 2017.

- 1 2 Mark Saunders; Adam Lea (July 4, 2017). July Forecast Update for Atlantic Hurricane Activity in 2017 (PDF) (Report). Tropical Storm Risk.

- ↑ Phillip J. Klotzbach; William M. Gray (July 5, 2017). "FORECAST OF ATLANTIC SEASONAL HURRICANE ACTIVITY AND LANDFALL STRIKE PROBABILITY FOR 2017" (PDF). Colorado State University. Retrieved July 5, 2017.

- ↑ Phillip J. Klotzbach; William M. Gray (August 4, 2017). "FORECAST OF ATLANTIC SEASONAL HURRICANE ACTIVITY AND LANDFALL STRIKE PROBABILITY FOR 2017" (PDF). Colorado State University. Retrieved August 4, 2017.

- ↑ Mark Saunders; Adam Lea (August 4, 2017). August Forecast Update for Atlantic Hurricane Activity in 2017 (PDF) (Report). Tropical Storm Risk.

- 1 2 "Early-season storms one indicator of active Atlantic hurricane season ahead". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. August 9, 2017.

- ↑ Phillip J. Klotzbach (December 14, 2016). "Qualitative Discussion of Atlantic Basin Seasonal Hurricane Activity for 2017" (PDF). Colorado State University. Retrieved December 24, 2016.

- ↑ Philip Klotzbach [@philklotzbach] (August 1, 2017). "#Emily is post-tropical. 1st 5 Atlantic TCs of 2017 combined for least ACE of 1st 5 TCs for any Atlantic season on record. 1988 old record" (Tweet). Retrieved August 2, 2017 – via Twitter.

- ↑ "@NWSOPC on Twitter: "W Atlantic rapid cyclogenesis produced #hurricane force winds, seas to 40 ft -- 2day satellite loop via GOES16 non-op and preliminary data"". Ocean Prediction Center. April 17, 2017. Retrieved April 20, 2017 – via Twitter.

- ↑ Lixion Avila (April 19, 2017). "Subtropical Depression One Discussion Number 1". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved April 19, 2017.

- ↑ Lixion Avila (April 19, 2017). Subtropical Depression One Advisory Number 1 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved April 22, 2017.

- ↑ "Subtropical Depression One Discussion Number 3". National Hurricane Center. April 19, 2017. Retrieved April 19, 2017.

- ↑ Lixion Avila (April 20, 2017). "Tropical Depression One Discussion Number 5". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved April 20, 2017.

- 1 2 Lixion Avila (April 20, 2017). "Tropical Storm Arlene Discussion Number 6". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved April 20, 2017.

- ↑ Lixion Avila (April 20, 2017). "Tropical Storm Arlene Discussion Number 7". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved April 20, 2017.

- ↑ Lixion Avila (April 21, 2017). "Post-Tropical Cyclone Arlene Discussion Number 9". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved April 21, 2017.

- ↑ Mike Tichacek (April 22, 2017). "Atlantic Tropical Weather Discussion: 2:04 PM EDT Sat Apr 22 2017". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved April 23, 2017.

- ↑ Formosa (April 23, 2017). "Atlantic Tropical Weather Discussion: 6:28 AM EDT Sun Apr 23 2017". National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on April 23, 2017. Retrieved April 23, 2017.

- ↑ "Tropical Storm Arlene Forms in the Atlantic; No Threat to Land". The Weather Channel. April 20, 2017. Retrieved April 20, 2017.

- ↑ Phillip Klotzbach (April 20, 2017). "The current central pressure of TS #Arlene of 990 mb is the lowest pressure for any April Atlantic TC or subtropical TC on record.". Twitter. Retrieved April 21, 2017.

- ↑ John P. Cangialosi (July 5, 2017). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Arlene (PDF) (Technical report). National Hurricane Center. p. 13. Retrieved July 21, 2017.

- ↑ Henson, Bob (May 11, 2017). "Adios, Adrian: Earliest Tropical Storm in East Pacific Annals Dissipates". Wunderground. Retrieved May 11, 2017.

- ↑ "NHC Graphical Outlook Archive". www.nhc.noaa.gov.

- ↑ "NHC Graphical Outlook Archive". National Hurricane Center. June 16, 2017. Retrieved June 18, 2017.

- ↑ "Potential Tropical Cyclone Two Discussion Number 1". National Hurricane Center. June 18, 2017. Retrieved June 18, 2017.

- ↑ "Tropical Storm Bret Discussion Number 5". National Hurricane Center. June 19, 2017. Retrieved June 19, 2017.

- ↑ Lixion A. Avila (June 20, 2017). "Remnants of Bret Advisory Number 9". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 23, 2017.

- ↑ Phil Klotzbach. "@philklotzbach on twitter: Tropical Storm #Bret has formed - earliest Atlantic MDR (<20°N, E of 70°W) named storm on record - prior record was Ana on 6/22/1979.". Twitter. Retrieved 19 June 2017.

- ↑ Phil Klotzbach. "@philklotzbach on twitter: Tropical Storm #Bret's named storm formation latitude of 9.4°N is the lowest latitude June named storm formation since 1933.". Twitter. Retrieved 20 June 2017.

- ↑ "Tropical Storm Bret blamed for at least one death". RJR News. June 21, 2017. Retrieved June 21, 2017.

- ↑ Gyasi Gonzales (June 20, 2017). "Man dies after slipping off makeshift bridge*". Daily Express. Retrieved June 22, 2017.

- ↑ Williams, Elizabeth (June 30, 2017). "Man injured when Bret destroyed home, has died". Trinidad Express. Retrieved July 1, 2017.

- ↑ John P. Cangialosi (June 13, 2017). "Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 22, 2017.

- ↑ John L. Beven II (June 16, 2017). "Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 22, 2017.

- ↑ Michael J. Brennan (June 19, 2017). Potential Tropical Cyclone Three Discussion Number 1 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 22, 2017.

- ↑ Michael J. Brennan (June 20, 2017). Tropical Storm Cindy Intermediate Advisory Number 4A (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 22, 2017.

- ↑ Stacy R. Stewart (June 21, 2017). Tropical Storm Cindy Discussion Number 6 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 22, 2017.

- ↑ Richard J. Pasch (June 22, 2017). Tropical Storm Cindy Discussion Number 11 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 22, 2017.

- ↑ Eryn Taylor (June 21, 2017). "Tropical Storm Cindy blamed in 10-year-old’s death". Fort Morgan, Alabama: WREG. Retrieved June 21, 2017.

- ↑ Wilborn P. Nobles III (June 22, 2017). "Death of man on Texas beach attributed to Tropical Storm Cindy: report". NOLA. Retrieved June 22, 2017.

- ↑ Evelyn Rivera-Acevedo (June 29, 2017). "Tropical Weather Discussion". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 5, 2017.

- ↑ Stacy R. Stewart (July 1, 2017). "Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 5, 2017.

- ↑ John P. Cangialosi (July 3, 2017). "Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 5, 2017.

- ↑ John P. Cangialosi (July 5, 2017). "Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 5, 2017.

- ↑ John L. Beven II (July 5, 2017). Tropical Depression Four Discussion Number 1 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 5, 2017.

- ↑ Lixion Avila (July 7, 2017). Remnants of Four Discussion Number 8 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 7, 2017.

- ↑ Eric S. Blake (July 15, 2017). "Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 18, 2017.

- ↑ Stacy R. Stewart (July 17, 2017). "Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 18, 2017.

- ↑ Daniel P. Brown (July 17, 2017). Tropical Storm Don Discussion Number 1 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 18, 2017.

- 1 2 Stacy R. Stewart (July 18, 2017). Tropical Storm Don Discussion Number 3 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 18, 2017.

- ↑ Daniel P. Brown (July 18, 2017). Tropical Storm Don Discussion Number 4 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 18, 2017.

- ↑ Robbie J. Berg (July 18, 2017). Remnants of Don Discussion Number 6 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 18, 2017.

- ↑ Stacy R. Stewart (July 30, 2017). "Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- ↑ "Tropical Depression Six Discussion Number 1". National Hurricane Center. July 31, 2017. Retrieved August 2, 2017.

- ↑ "Tropical Storm Emily Special Discussion Number 2". National Hurricane Center. July 31, 2017. Retrieved August 2, 2017.

- ↑ "Tropical Depression Emily Discussion Number 5". National Hurricane Center. July 31, 2017. Retrieved August 2, 2017.

- ↑ "Post-Tropical Cyclone Emily Discussion Number 9". National Hurricane Center. August 2, 2017. Retrieved August 2, 2017.

- ↑ "Gov. Scott declares a State of Emergency for Tropical Storm Emily". WLTV. July 31, 2017. Retrieved July 31, 2017.

- ↑ Dan Noah (August 1, 2017). Public Information Statement (Report). National Weather Service Tampa, Florida. Retrieved August 1, 2017.

- ↑ Preliminary Local Storm Report (Report). Iowa Environmental Mesonet. National Weather Service Weather Forecast Office in Miami, Florida. August 1, 2017. Retrieved August 2, 2017.

- ↑ Vanessa Borge (August 2, 2017). "Pump Outage To Blame In Miami Beach Flooding". CBS Miami. Retrieved August 2, 2017.

- ↑ "Miami Beach Drying Out After Tuesday’s Torrential Downpours". CBS Miami. August 2, 2017. Retrieved August 2, 2017.

- ↑ Preliminary Local Storm Report (Report). Iowa Environmental Mesonet. National Weather Service Weather Forecast Office in Miami, Florida. August 1, 2017. Retrieved August 2, 2017.

- ↑ "NHC Graphical Outlook Archive". National Hurricane Center. August 3, 2017. Retrieved August 7, 2017.

- 1 2 Richard Pasch (August 6, 2017). "Potential Tropical Cyclone Seven Discussion Number 1". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 7, 2017.

- ↑ Daniel Brown (August 7, 2017). "Tropical Storm Franklin Discussion Number 2". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 7, 2017.

- ↑ Stacy Stewart (August 8, 2017). "Tropical Storm Franklin Tropical Cyclone Update". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 9, 2017.

- ↑ Stacy Stewart (August 8, 2017). "Tropical Storm Franklin Discussion Number 7". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 9, 2017.

- 1 2 http://7newsbelize.com/sstory.php?nid=41443

- ↑ https://www.upi.com/Top_News/World-News/2017/08/08/Tropical-Storm-Franklin-enters-gulf-waters-expected-to-strengthen/4651502101786/

- ↑ http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/text/refresh/MIATCPAT2+shtml/100541.shtml

- ↑ "Tropical Cyclone Names#Atlantic". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved December 24, 2016.

- ↑ Erik Ortiz (July 18, 2017). "Tropical Storm Don Develops in Atlantic, but Its Name Is Not a Political Jab". NBC News. Retrieved July 19, 2017.

- ↑ "Tropical Storms ‘Don’ And ‘Hilary’ Bring Out Political Jokes On Twitter". WBZ-TV. July 19, 2017. Retrieved July 19, 2017.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to 2017 Atlantic hurricane season. |

- National Hurricane Center's website

- National Hurricane Center's Atlantic Tropical Weather Outlook

- Tropical Cyclone Formation Probability Guidance Product