Rood

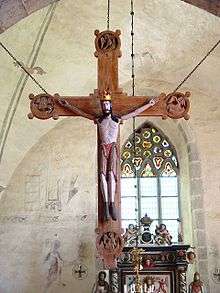

A rood or rood cross, sometimes known as a triumphal cross,[1] is a cross or crucifix, especially the large Crucifixion set above the entrance to the chancel of a medieval church.[2] Alternatively, it is a large sculpture or painting of the crucifixion of Jesus.

Derivation

Rood is an archaic word for pole, from Old English rōd "pole", specifically "cross", from Proto-Germanic *rodo, cognate to Old Saxon rōda, Old High German ruoda "rod".[3]

Rood was originally the only Old English word for the instrument of Jesus Christ's death. The words crúc and in the North cros (from either Old Irish or Old Norse) appeared by late Old English; "crucifix" is first recorded in English in the Ancrene Wisse of about 1225.[4] More precisely, the Rood was the True Cross, the specific wooden cross used in Christ's crucifixion. The word remains in use in some names, such as Holyrood Palace and the Old English poem The Dream of the Rood. The phrase "by the rood" was used in swearing, e.g. "No, by the rood, not so" in Shakespeare's Hamlet (Act 3, Scene 4).

The alternative term triumphal cross (Latin: crux triumphalis, German: Triumphkreuz), which is more usual in Europe, signifies the triumph that the resurrected Jesus Christ (Christus triumphans) won over death.[5]

Position

In church architecture the rood, or rood cross, is a life-sized crucifix displayed on the central axis of a church, normally at the chancel arch. The earliest roods hung from the top of the chancel arch (rood arch), or rested on a plain "rood beam" across it, usually at the level of the capitals of the columns. This original arrangement is still found in many churches in Germany and Scandinavia, although many other surviving crosses now hang on walls.

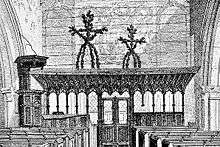

If the choir is separated from the church interior by a rood screen, the rood cross is placed on, or more rarely in front of, the screen.[6][7] Under the rood is usually the altar of the Holy Cross.

History

Numerous near life-size crucifixes survive from the Romanesque period or earlier, with the Gero Cross in Cologne Cathedral (AD 965–970) and the Volto Santo of Lucca the best known. The prototype may have been one known to have been set up in Charlemagne's Palatine Chapel in Aachen, apparently in gold foil worked over a wooden core in the manner of the Golden Madonna of Essen,[8] though figureless jeweled gold crosses are recorded in similar positions in Hagia Sophia in Constantinople in the 5th century. Many figures in precious metal are recorded in Anglo-Saxon monastic records, though none now survive. Notables sometimes gave their crowns (Cnut the Great at Winchester Cathedral), necklaces (Lady Godiva to the Virgin accompanying the rood at Evesham Abbey), or swords (Tovi the Proud, Waltham Abbey) to decorate them.[9] The original location and support for the surviving figures is often unclear but a number of northern European churches preserve the original setting in full — they are known as a Triumphkreuz in German, from the "triumphal arch" (or "chancel arch") of Early Christian architecture. As in later examples the Virgin and Saint John often flank the cross, and cherubim and other figures are sometimes seen. A gilt rood in the 10th-century Mainz Cathedral was only placed on a beam on special feast days.[10]

Components

Image of Christ

In the Romanesque era the crucified Christ was presented as ruler and judge. Instead of a crown of thorns he wears a crown or a halo, on his feet he wears "shoes" as a sign of the ruler. He is victorious over death. His feet are parallel to each other on the wooden support ("Four nail type") and not one on top of the other.[11] The perizoma (loincloth) is highly stylized and falls in vertical folds.

In the transition to the Gothic style, the triumphant Christ becomes suffering Christ, the pitiful Man of Sorrows. Instead of the ruler's crown, he wears the crown of thorns, his feet are placed one above the other and are pierced with a single nail. His facial expression and posture express his pain. The wounds of the body are often dramatically portrayed. The loincloth is no longer so clearly stylized. The attendant figures Mary and John show signs of grief.[12]

Attendant figures

A triumphal cross may be surrounded by a group of people. These people may include Mary and John, the "beloved disciple" (based on John's Gospel (John 19:25-27, Matthew 27:25f, Mark 15;40f and Luke 23:49)), but also apostles, angels and the benefactor.

- The triumphal cross of Öja Church in Öja on Gotland stands on a transverse beam beneath the triumphal arch and is flanked by two people: Mary and John.

- The triumphal cross in the abbey church of Wechselburg stands in an elevated position on the rood screen and also has the same pair of attendant figures.

- The triumphal cross in Schwerin Cathedral is also flanked by Mary and John. At the end of the cross' beam the Evangelist's symbols may be seen.

- In St. Mary's Church in Osnabrück there are only the empty stone pedestals of the attendant figures.

- The triumphal cross above the screen in Halberstadt Cathedral is not flanked by Mary and John, but by two angels.

- On the supporting beam of the triumphal cross in Lübeck Cathedral there is also a bishop, presumably the benefactor of the cross.

Rood screens

Rood screens developed in the 13th century, as a wooden or stone screens, also usually separating the chancel or choir from the nave, upon which the rood now stood. The screen may be elaborately carved and was often richly painted and gilded. Rood screens were found in Christian churches in most parts of Europe by the end of the Middle Ages, though in Catholic countries the great majority were gradually removed after the Council of Trent, and most were removed or drastically cut down in areas controlled by Calvinists and Anglicans. The best medieval examples are now mostly in the Lutheran countries such as Germany and Scandinavia, where they were often left undisturbed in country churches.

Rood screens are the Western equivalent of the Byzantine templon beam, which developed into the Eastern Orthodox iconostasis. Some rood screens incorporate a rood loft, a narrow gallery or just flat walkway which could be used to clean or decorate the rood or cover it up in Lent, or in larger examples by singers or musicians. An alternative type of screen is the Pulpitum, as seen in Exeter Cathedral, which is near the main altar of the church.

The rood itself provided a focus for worship, most especially in Holy Week, when worship was highly elaborate. During Lent the rood was veiled; on Palm Sunday it was revealed before the procession of palms and the congregation knelt before it. The whole Passion story would then be read from the rood loft, at the foot of the crucifix, by three ministers.

No original medieval rood now survives in a church in the United Kingdom.[13] Most were deliberately destroyed as acts of iconoclasm during the English Reformation and the English Civil War, when many rood screens were also removed. Today, in many British churches, the "rood stair" that gave access to the gallery is often the only remaining sign of the former rood screen and rood loft.

In the nineteenth century, under the influence of the Oxford Movement, roods and screens were again added to many Anglican churches.

Representative examples

Cross from Linde Church on Gotland (today in the Swedish History Museum) also displays the symbol of a ruler, demonstrating the origin of the name.

Cross from Linde Church on Gotland (today in the Swedish History Museum) also displays the symbol of a ruler, demonstrating the origin of the name. Triumphal cross of Notke in Lübeck Cathedral

Triumphal cross of Notke in Lübeck Cathedral.jpg) Triumphal cross (Christ's side) in Doberan Minster

Triumphal cross (Christ's side) in Doberan Minster The "plate cross" (Scheibenkreuz) in St. Mary's (Hohnekirche) in Soest (around 1200)

The "plate cross" (Scheibenkreuz) in St. Mary's (Hohnekirche) in Soest (around 1200) Forked cross in St. Peter's at Merzig

Forked cross in St. Peter's at Merzig

Germany

- the Gero Cross in Cologne Cathedral

- the Ottonian Cross in Kollegiatskirche St. Peter und Alexander, Aschaffenburg

- the Helmstedt Cross in the treasure chamber of Werden Abbey

- the triumphal cross in Lübeck Cathedral from the workshop of Bernt Notke, 1477, height 17 m

- in St. Catherine's Church, Lübeck, around 1450

- in Halberstadt Cathedral

- in Wechselburg Abbey, Holy Cross basilica

- in Naumburg Cathedral

- in Doberan Minster

- in Schwerin Cathedral (from St. Mary's, Wismar)

- in Osnabrück in St. Mary's and in St. Peter's Cathedral

- in Alfeld (Leine) in St. Nicholas' Church, around 1250

- in Havelberg Cathedral, 1270/80

- in Soest, St. Maria zur Höhe, the so-called plate cross (Scheibenkreuz)

- in Haseldorf, St. Gabriel's

- in Dinslaken, St. Vincent around 1310

Sweden

- On Gotland in several of the medieval churches, including Alskog, Alva, Bro, Fide, Fröjel, Grötlingbo, Hamra, Hemse, Klinte, Lye, Öja, Rute, Stenkumla and Stenkyrka. The one at Öja is particularly lavish.

United Kingdom

- Church of the Annunciation, Marble Arch, London

- St Augustine's, Kilburn, London

- St Gabriel's, Warwick Square, London

- Grosvenor Chapel, Mayfair, London

- St Mary-le-Bow, London

- St Matthew's Church, Sheffield

- Peterborough Cathedral

- Church of St Protus and St Hyacinth, Blisland

The Charlton-on-Otmoor Garland

A unique rood exists at St Mary's parish church, Charlton-on-Otmoor, near Oxford, England, where a large wooden cross, solidly covered in greenery, and known as the Garland, stands on the early 16th-century rood screen (said by Sherwood and Pevsner to be the finest in Oxfordshire).[14] The cross is redecorated twice a year, on 1 May and 19 September (the patronal festival, calculated according to the Julian Calendar), when children from the local primary school, carrying small crosses decorated with flowers, bring a long, flower-decorated, rope-like garland. The cross is dressed or redecorated with locally obtained box foliage. The rope-like garland is hung across the rood screen during the "May Garland Service".[15]

An engraving from 1823 shows the dressed rood cross as a more open, foliage-covered framework, similar to certain types of corn dolly, with a smaller attendant figure of similar appearance. Folklorists have commented on the garland crosses' resemblance to human figures, and noted that they replaced statues of St Mary and Saint James the Great which had stood on the rood screen until they were destroyed during the Reformation. Until the 1850s, the larger garland cross was carried in a May Day procession, accompanied by morris dancers, to the former Benedictine Studley priory (as the statue of St Mary had been, until the Reformation). Meanwhile, the women of the village used to carry the smaller garland cross through Charlton,[15] though it seems that this ceased some time between 1823 and 1840, when an illustration in J.H. Parker's A Glossary of Terms Used in Grecian, Roman, Italian, and Gothic Architecture shows only one garland cross, centrally positioned on the rood screen.[16]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Gothic Sculpture, 1140-1300 by Paul Williamson (1998). Retrieved 26 Oct 2014.

- ↑ Curl, James Stevens (2006). Oxford Dictionary of Architecture and Landscape Architecture, 2nd ed., OUP, Oxford and New York, p. 658. ISBN 978-0-19-860678-9.

- ↑ Oxford English Dictionary, "Rood"

- ↑ Oxford English Dictionary, "Cross", and "Crucifix"

- ↑ Margarete Luise Goecke-Seischab / Jörg Ohlemacher: Kirchen erkunden, Kirchen erschließen, Ernst Kaufmann, Lahr 1998, p. 232

- ↑ E.g. in the abbey church of Wechselburg

- ↑ In England the name "rood screen" indicates that there is a (monumental) cross, even if the original cross has not survived.

- ↑ Schiller, 141–146

- ↑ Dodwell, 210–215

- ↑ Schiller, 140

- ↑ Torsten Droste: Romanische Kunst in Frankreich, DuMont Kunstreiseführer, Cologne, 1992(2), pp. 32f

- ↑ Formen der Kunst. Teil II. Die Kunst im Mittelalter, bearbeitet von Wilhelm Drixelius, Verlag M. Lurz, Munich, o.J. p. 71 and p. 88

- ↑ Duffy, 1992, page not cited

- ↑ Sherwood & Pevsner, 1974, page 530

- 1 2 Hole, 1978, pages 113–114

- ↑ Parker, 1840, page not cited

References

- Dodwell, C.R. (1985) [1982]. Anglo-Saxon Art, A New Perspective. Manchester University Press / Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-7190-0926-X.

- Duffy, Eamon (1992). The Stripping of the Altars: Traditional Religion in England, 1400-1580. Yale: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-06076-9.

- Hole, Christina (1978). A Dictionary of British Folk Customs. Granada Publishing Ltd / Paladin Press. pp. 113–114. ISBN 0-586-08293-X.

- Parker, J.H. (1840). A Glossary of Terms Used in Grecian, Roman, Italian, and Gothic Architecture. Oxford.

- Sherwood, Jennifer; Pevsner, Nikolaus (1974). Oxfordshire. The Buildings of England. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. p. 530. ISBN 0-14-071045-0.

- Schiller, G. (1972). Iconography of Christian Art. II. London: Lund Humphries. pp. not stated; figures 471–75. ISBN 0-85331-324-5.

- Simpson, Jacqueline; Roud, Steve (2000). A Dictionary of English Folklore. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-210019-X.

Further reading

- Manuela Beer: Triumphkreuze des Mittelalters. Ein Beitrag zu Typus und Genese im 12. und 13. Jahrhundert. Mit einem Katalog der erhaltenen Denkmäler ("Rood Crosses of the Middle Ages. An Article on the Typology and Genesis in the 12th and 13th Centuries. With a catalogue of surviving monuments"). Schnell & Steiner, Regensburg, 2005, ISBN 3-7954-1755-4

- Der Erlöser am Kreuz: Das Kruzifix ("The Saviour on the Cross: the Crucifix"), rescissions in the portrayal of the Crucifix or Rood Cross.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Rood screens. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Rood cross. |

- Archbishops' Council. "St. Mary's, Charlton-on-Otmoor". A Church Near You. Church of England. Retrieved 4 November 2007.

- "Rood". Catholic Encyclopedia.