Triptychs by Francis Bacon

The Irish-born artist Francis Bacon (1909–1992) painted 28 known[1] triptychs between 1944 and 1986.[2] He began to work in the format in the mid-1940s with a number of smaller scale formats before graduating in 1962 to large examples. He followed the larger style for 30 years, although he painted a number of smaller scale triptychs of friend's heads, and after the death of his former lover George Dyer in 1971, the three Black Triptychs.

Overview

Bacon was a highly mannered artist often preoccupied with forms, themes, images and modes of expression that he would rework for sustained periods, often across decades. When asked about his tendency for sequential paintings, he explained how, in his mind, images revealed themselves "in series. And I suppose I could go long beyond the triptych and do five or six together, but I find the triptych is a more balanced unit."[3] His career began with the 1944 triptych Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion, an instant critical and popular success. The format appealed to him; he said, "I see images in series", according to Bacon images suggested other images and series became his dominant motif. He moved past the triptych format, and from the late 40s to the late 50s produced works in series of up to 10 works, many of which rank amongst his finest, including his series of Popes, heads and men in suits.

Bacon fell from critical favour in the late 1950s having been a darling for the previous 10 years. He later admitted he had lost his voice and was seeking a new way to express himself which involved a lot of transitional work, much of which he destroyed, and much of which he preferred not to be included in his cannon. His 1962 Three Studies for a Crucifixion, painted to coincide with his first retrospective at the Tate, marked a return to form and has been highly praised by critics and historians such as David Sylvester, Michel Leiris and Michael Peppiatt as a key turning point in his career.

He told critics that his usual practice with triptychs was to begin with the left panel and work across. Typically he completed each frame before beginning the next. As the work as a whole progressed, he would sometimes return to an earlier panel to make revisions, though this practice was generally carried out late in the overall work's completion.[4]

Works

During the late 1940s and 1950s, Bacon worked on several series, such as his screaming heads, popes, animals in prey and men in blue suits. The use of reworked and revisited imagery transferred into regular use of a triptych format in the early 1960s.[4] In interviews, Bacon said that when he daydreamed, images occurred in "hundreds at a time, some link up with one another." The triptych format was attractive, he believed, because it physically broke the images and prevented forced or constructed narrative interpretation; a tendency in painting to which he was particularly opposed and found banal.[4]

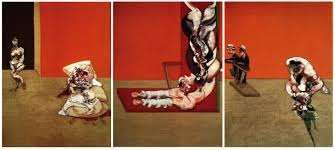

Bacon began his first large triptych Three Studies for a Crucifixion in February 1962. Although he often completed a major canvas in a day, this work was not finished until the following March. At 194 cm x 145 cm,[2] it is four times the size of his previous triptych and his first major work, the 1944 Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion, with which the 1962 work shares both theme and title.[3] In 1964, he extended the standard width of each canvas by 2.5 cm, and discounting the mid-1960s heads and early-mid "Black Triptychs", retained the larger, monumental scale for all triptychs painted in the remaining thirty years of his life.[2]

In 2000, the art critic David Sylvester categorised Bacon's large triptychs into three groupings: 18 showing a dramatic or erotic event, six showing three full-length seated portraits, and four containing single nude figures. 36 contain a single nude figure, 24 a single clothed figure. Five show a biomorph,[a 1] 4 contain still lives.[2] 28 are large, generally five times bigger than the small format works. Bacon was highly self-critical and destroyed a great many canvases.[a 2] It is known that at least five were destroyed, while two or three were likely split by dealers and sold as individual canvasses.[2]

Crucifixions

As well as being Bacon's first large format triptych, Three Studies for a Crucifixion introduced the later and often repeated visual motif a human body turned inside out. This idea was drawn from a long tradition in art history, and was influenced strongly by Rembrandt's Side of beef and Chaim Soutine's Carcass of Beef.[5]

Although the idea of torn flesh was present in early work such as his Painting (1946), in the 1960s triptychs and the two versions of the Lying figure with Hypodermic Syringe (1963 & 1968), Bacon inverts the epidermis and guts of human torsos to create imagery, according to Sylvester, nearing the grotesque and horror of Rubens's Descent from the Cross, and the Crucifix panel of Cimabue.[5] His first three major triptychs were of crucifixion scenes, and all bear debt to Rubens's The Descent from the Cross, a work the normally reticent Bacon praised time and again to critics.

Heads

After 1965 Bacon's focus generally narrowed, and he became obsessed with close-up portraiture. On the opening day of his first Tate retrospective, he received word that his former lover Peter Lacey had died; news that had a devastating impact on him personally, and led him to produce his first triptych in the style to his heads of the mid-1950s, which had brought him to wider attention.[6]

The 1962 Study for Three Heads opened a dramatically new arena for the artist and was followed by similar scaled triptychs for a series of works which can loosely be seen to be painted after his "Colony Room associates, including Dyer, Lucian Freud (for a period), Muriel Belcher and Henrietta Moraes. From the 1970s, as the artist himself approached later life, associates and drinking friends began to die, lending many of the portraits an added urgency and poignancy.

Voyeur

.jpg)

In Triptych Inspired by T. S. Eliot's poem "Sweeney Agonistes", Bacon shows a couple erotically entwined in the right-hand panel, while a clothed male figure stands looking at them. The left-hand panel shows another couple, in full view, lying in Post-coital tristesse. Here Bacon is looking at the notion of voyeurism being an ideal prelude to participation; a notion held by his former lover Peter Lacy. The idea is revisited in both versions of Triptych - Studies from the Human Body (1970), and is informed by Henri Matisse's Red Studio of 1911.[7]

Bacon's triptychs show ten separate couples on beds, of which eight are erotically interacting, while in two others figures are shown sleeping side by side.[2]

The Black Triptychs

Two days before the opening of Bacon's retrospective at the Grand Palais, George Dyer, his former lover and principal model for the past seven years, took his own life in the hotel room they were sharing.[8] Bacon's acute sense of mortality and awareness of the fragility of life were heightened by Dyer's death. During the following three years he painted many images of Dyer, including the series of three "Black triptychs" (or "Black paintings") which have come to be seen as among his best work. They are so named because they share common black backgrounds emblematic of death or mourning .[8]

A number of characteristics bind the "Black triptychs" together. The form of a monochromatically rendered doorway features centrally in all, and each is framed by flat and shallow walls.[9] In each, Dyer is stalked by a broad shadow; which takes the form of pools of blood or flesh in the first and third panels, and the wings of the angel of death in the second and first.[10] In its display caption for the Triptych–August 1972 the Tate gallery wrote, "What death has not already consumed seeps incontinently out of the figures as their shadows."[11]

Bacon's work from the 1970s has been described by the art critic Hugh Davies as the "frenzied momentum of a struggle against death". He admitted during a 1974 interview that he thought the most difficult aspect of aging was "losing your friends". This was a bleak period in his life, and though he was to live for another seventeen years, he felt that his life was almost over, "and all the people I've loved are dead". His concern is reflected in the darkened flesh and background tones of these three triptychs.[9]

Themes

Motion

Bacon's interest in sequential images came from his interest in photography, in particular his fascination with the work of the English pioneer Eadweard Muybridge (1830–1904). He also was impressed with Michelangelo's The Three Labours of Hercules (c. 1528). These works captured movement in a series of frozen moments, shown in separate plates recorded or captured in quick succession, allowing the viewer to witness multiple perspectives.[12]

Footnotes

References

- ↑ Bacon was a ruthless self-editor, likely many more were destroyed

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Sylvester, 107

- 1 2 Sylvester, 100

- 1 2 3 Davies & Yard, 114

- 1 2 3 Sylvester, 108

- ↑ Sylvester, 111

- ↑ Sylvester, 121-22

- 1 2 "Triptych - August 1972". Tate. Retrieved February 13, 2010.

- 1 2 Davies; Yard, 65

- ↑ Davies & Yard, 67–76.

- ↑ "Triptych - August 1972". Tate. Retrieved on February 11, 2010.

- ↑ Zielinski, Siegfried. Audiovisions: cinema and television as entr'actes in history. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 1999. 58. ISBN 90-5356-313-X

Bibliography

- Baldassari, Anne. Bacon and Picasso. Flammarion, 2005. ISBN 2-08-030486-0

- Davies, Hugh; Yard, Sally. Francis Bacon. New York: Cross River Press, 1986. ISBN 0-89659-447-5

- Dawson, Barbara; Sylvester, David. Francis Bacon in Dublin. London: Thames & Hundson, 2002. ISBN 0-500-28254-4

- Farr, Dennis; Peppiatt, Michael; Yard, Sally. Francis Bacon: A Retrospective. Harry N Abrams, 1999. ISBN 0-8109-2925-2

- Russell, John. Francis Bacon (World of Art). Norton, 1971. ISBN 0-500-20169-2

- Sylvester, David. Looking back at Francis Bacon. London: Thames and Hudson, 2000. ISBN 0-500-01994-0