Instant-runoff voting

| Part of the Politics series |

| Electoral systems |

|---|

|

Plurality/majoritarian |

|

|

|

Other

|

|

|

Instant-runoff voting (IRV), also known as the alternative vote (AV) or transferable vote, is a voting method used in single-seat elections with more than two candidates. (It is also sometimes referred to as "ranked-choice voting" (RCV) and "preferential voting", although there are other preferential voting methods that use ranked-choice ballots.)

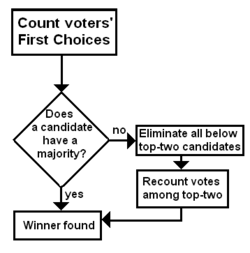

Instead of voting only for a single candidate, voters in IRV elections can rank the candidates in order of preference. Ballots are initially counted for each elector's top choice. If a candidate secures more than half of these votes, that candidate wins. Otherwise, the candidate in last place is eliminated and removed from consideration. The top remaining choices on all the ballots are then counted again. This process repeats until one candidate is the top remaining choice of a majority of the voters. When the field is reduced to two, it has become an "instant runoff" that allows a comparison of the top two candidates head-to-head.

IRV has the effect of avoiding split votes when multiple candidates earn support from like-minded voters. For example, suppose there are two similar candidates A & B, and a third opposing candidate C, with first-preference totals of 35% for candidate A, 25% for B and 40% for C. In a plurality voting method, candidate C may win with 40% of the votes, even though 60% of electors prefer both A and B over C. Alternatively, voters are pressured to choose the seemingly stronger candidate of either A or B, despite personal preference for the other, in order to help ensure the defeat of C. With IRV, the electors backing B as their first choice can rank A second, which means candidate A will win by 60% to 40% over C despite the split vote in first choices.

Instant-runoff voting is used in national elections in several countries. For example, it is used to elect: members of the Australian House of Representatives and most Australian state legislatures;[1] the President of India and members of legislative councils in India; the President of Ireland;[2] members of Congress in Maine in the United States;[3] and the parliament in Papua New Guinea. The method is also used in local elections around the world, as well as by some political parties (to elect internal leaders) and private associations, for various voting purposes such as that for choosing the Academy Award for Best Picture. IRV is described in Robert's Rules of Order Newly Revised under the name "preferential voting".[4]

Terminology

Instant-runoff voting derives its name from the way the ballot count simulates a series of runoffs, similar to a two-round system, except that voter preferences do not change between rounds.[5] It is also known as the alternative vote, transferable vote, ranked-choice voting (RCV), single-seat ranked-choice voting, or preferential voting.[6] Britons and Canadians[7] generally call IRV the "Alternative Vote" (AV). Australians, who use IRV for most single winner elections, call IRV "preferential voting," as does Robert's Rules of Order. IRV occasionally is referred to as Ware's method after its inventor, American William Robert Ware. Americans generally call IRV "ranked choice voting," including in jurisdictions using it such as San Francisco, California; Maine; and Minneapolis, Minnesota.

When the single transferable vote (STV) method is applied to a single-winner election it becomes IRV. Some Irish observers mistakenly call IRV "proportional representation" based on the fact that the same ballot form is used to elect its president by IRV and parliamentary seats by STV, but IRV is a winner-take-all election method.

North Carolina law uses "instant runoff" to describe the contingent vote or "batch elimination" form of IRV in one-seat elections. A single second round of counting produces the top two candidates for a runoff election. [8] Election officials in Hendersonville, North Carolina use "instant runoff" to describe a multi-seat election method that simulates in a single round of voting their previous method of multi-seat runoffs.[9] State law in South Carolina[10] and Arkansas[11] use "instant runoff" to describe the practice of having certain categories of absentee voters cast ranked-choice ballots before the first round of a runoff and counting those ballots in any subsequent runoff elections.

Variations

There are a number of variations in IRV. IRV methods in use in different countries vary both as to ballot design and as to whether or not voters are obliged to provide a full list of preferences.

In an optional preferential voting system, voters can give a preference to as many candidates as they wish. They may make only a single choice, known as "bullet voting", and some jurisdictions accept an "X" as valid for the first preference. This may result in ballot exhaustion, where all the voters' preferences are eliminated before a candidate is elected with a majority. Optional preferential voting is used for elections for the President of Ireland and the Western Australian Legislative Assembly.

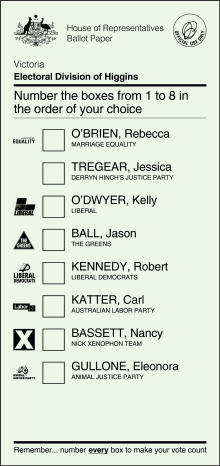

In a full preferential voting method, voters are required to mark a preference for every candidate standing.[12] Ballots that do not contain a complete ordering of all candidates are in some jurisdictions considered spoilt or invalid, even if there are only two candidates standing. This can become burdensome in elections with many candidates and can lead to "donkey voting", in which some voters simply choose candidates at random or in top-to-bottom order, or a voter may order his or her preferred candidates and then fill in the remainder on a donkey basis. Full preferential voting is used for elections to the Australian federal parliament and for most State parliaments.

Other methods only allow marking a preference for the voter's top three favorites.[13]

History

Instant-runoff voting was devised in 1871 by American architect William Robert Ware,[14] although it is, in effect, a special case of the single transferable vote method, which emerged independently in the 1850s. Unlike the single transferable vote in multi-seat elections, however, the only ballot transfers are from backers of candidates who have been eliminated.

The first known use of an IRV-like method in a governmental election was in the 1893 general election in the Colony of Queensland (in present-day Australia).[15] The variant used for this election was a "contingent vote". IRV in its true form was first used in Western Australia, in the 1908 state election. The Hare-Clark system was introduced for the Tasmanian House of Assembly at the 1909 state election.

IRV was introduced for federal (nationwide) elections in Australia after the Swan by-election in October 1918, in response to the rise of the conservative Country Party, representing small farmers. The Country Party split the non-Labor vote in conservative country areas, allowing Labor candidates to win without a majority of the vote. The conservative government of Billy Hughes introduced IRV (in Australia called "preferential voting") as a means of allowing competition between the Coalition parties without putting seats at risk. It was first used at the Corangamite by-election on 14 December 1918, and at a national level at the 1919 election.[16] IRV continued to benefit the Coalition until the 1990 election, when for the first time Labor obtained a net benefit from IRV.[17]

Election procedure

Process

In instant-runoff voting, as with other ranked election methods, each voter ranks the list of candidates in order of preference. Under a common ballot layout, the voter marks a '1' beside the most preferred candidate, a '2' beside the second-most preferred, and so forth, in ascending order. This is shown in the example Australian ballot above.

The mechanics of the process are the same regardless of how many candidates the voter ranks, and how many are left unranked. In some implementations, the voter ranks as many or as few choices as they wish, while in other implementations the voter is required to rank either all candidates, or a prescribed number of them.

In the initial count, the first preference of each voter is counted and used to order the candidates. Each first preference counts as one vote for the appropriate candidate. Once all the first preferences are counted, if one candidate holds a majority, that candidate wins. Otherwise the candidate who holds the fewest first preferences is eliminated. If there is an exact tie for last place in numbers of votes, various tie-breaking rules determine which candidate to eliminate. Some jurisdictions eliminate all low-ranking candidates simultaneously whose combined number of votes is fewer than the number of votes received by the lowest remaining candidates.

Ballots assigned to eliminated candidates are recounted and assigned to one of the remaining candidates based on the next preference on each ballot. The process repeats until one candidate achieves a majority of votes cast for continuing candidates. Ballots that 'exhaust' all their preferences (all its ranked candidates are eliminated) are set aside.

In Australian elections the allocation of preferences is performed efficiently at the polling booth by having the returning officer pre-declare the two likely winners. (In the event that the returning officer is wrong the votes need to be recounted.)

Candidate order on the ballot paper

The common way to list candidates on a ballot paper is alphabetically or by random lot. In some cases, candidates may also be grouped by political party. Alternatively, Robson Rotation involves randomly changing candidate order for each print run.

Party strategies

Where preferential voting is used for the election of an assembly or council, parties and candidates often advise their supporters on their lower preferences, especially in Australia where a voter must rank all candidates to cast a valid ballot. This can lead to "preference deals", a form of pre-election bargaining, in which smaller parties agree to direct their voters in return for support from the winning party on issues critical to the small party. However, this relies on the assumption that supporters of a minor party will mark preferences for another party based on the advice that they have been given.

Counting logistics

Most IRV elections historically have been tallied by hand, including in elections to Australia's House of Representatives and most state governments. In the modern era, voting equipment can be used to administer the count either partially or fully.

In Australia, the returning officer now usually declares the two candidates that are most likely to win each seat. The votes are always counted by hand at the polling booth monitored by scrutineers from each candidate. The first part of the count is to record the first choice for all candidates. Votes for candidates other than the two likely winners are then allocated to them in a second pass. The whole process of counting the votes by hand and allocating preferences is typically completed within two hours on election night at a cost of $7.68 per elector in 2010 to run the entire election.[18]

(The declaration by the returning officer is simply to optimize the counting process. In the unlikely event that the returning officer is wrong and a third candidate wins, then the votes would simply have to be counted a third time.)[19]

Ireland in its presidential elections has several dozen counting centers around the nation. Each center reports its totals and receives instructions from the central office about which candidate or candidates to eliminate in the next round of counting based on which candidate is in last place. The count typically is completed the day after the election, as in 1997.[20]

In the United States, some Californian cities, e.g. Oakland and San Francisco, administer IRV elections on voting machines, with optical scanning machines recording preferences and software tallying the IRV algorithm as soon as ballots are tallied.[21] Cary, North Carolina's pilot program in 2007 tallied first choices on optical scan equipment at the polls and then used a central hand-count for the IRV tally.[22] Portland, Maine in 2011 used its usual voting machines to tally first choice at the polls, then a central scan with different equipment if an IRV tally was necessary.[23]

Examples

Some examples of IRV elections are given below. The first two (fictional elections) demonstrate the principle of IRV. The others offer examples of the results of real elections.

Five voters, three candidates

A simple example is provided in the accompanying table. Three candidates are running for election, Bob, Bill and Sue. There are five voters, "a" through "e". The voters each have one vote. They rank the candidates first, second and third in the order they prefer them. To win, a candidate must have a majority of vote; that is, three or more.

In Round 1, the first-choice rankings are tallied, with the results that Bob and Sue both have two votes and Bill has one. No candidate has a majority, so a second "instant runoff" round is required. Since Bill is in bottom place, he is eliminated. The ballot ranking him first is added to the totals of the candidate listed second. This results in the Round 2 votes as seen below. This gives Sue 3 votes, which is a majority.

| Round 1 | Round 2 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Candidate | a | b | c | d | e | Votes | a | b | c | d | e | Votes |

| Bob | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Sue | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Bill | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | ||||||

Tennessee capital election

Most instant-runoff voting elections are won by the candidate who leads in first-choice rankings. In such cases, IRV chooses the same winner as first-past-the-post voting. Some IRV elections are won by a candidate who finishes second after the first-round count. In this case, IRV chooses the same winner as a two-round system if all voters were to vote again and maintain their same preferences. A candidate may also win who is in third place or lower after the first count, but gains majority support in the final round. In such cases, IRV would choose the same winner as a multi-round method that eliminated the last-place candidate before each new vote, assuming all voters kept voting and maintained their same preferences. Here is an example of this last case.

Imagine that Tennessee is having an election on the location of its capital. The population of Tennessee is concentrated around its four major cities, which are spread throughout the state. For this example, suppose that the entire electorate lives in these four cities and that everyone wants to live as near to the capital as possible.

The candidates for the capital are:

- Memphis, the state's largest city, with 42% of the voters, but located far from the other cities

- Nashville, with 26% of the voters, near the center of the state

- Knoxville, with 17% of the voters

- Chattanooga, with 15% of the voters

The preferences of the voters would be divided like this:

| 42% of voters (close to Memphis) |

26% of voters (close to Nashville) |

15% of voters (close to Chattanooga) |

17% of voters (close to Knoxville) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

In the first round no city gets a majority:

| Votes in round/ City Choice | 1st |

|---|---|

| Memphis | 42% |

| Nashville | 26% |

| Knoxville | 17% |

| Chattanooga | 15% |

If one of the cities had achieved a majority vote (more than half), the election would end there. If this were a first-past-the-post election, Memphis would win because it received the most votes. But IRV does not allow a candidate to win on the first round without having an absolute majority of the vote. While 42% of the electorate voted for Memphis, 58% of the electorate voted against Memphis in this first round.

So we move to the second round of tabulation to determine which of the front-running cities had broader support. Chattanooga received the lowest number of votes in the first round, so it is eliminated. The ballots that listed Chattanooga as "first-choice" are added to the totals of the second-choice selection on each ballot. Everything else stays the same.

Chattanooga's 15% of the total votes are added to the second choices selected by the voters for whom that city was first-choice (in this example Knoxville):

| Votes in round/ City Choice | 1st | 2nd |

|---|---|---|

| Memphis | 42% | 42% |

| Nashville | 26% | 26% |

| Knoxville | 17% | 32% |

| Chattanooga | 15% |

In the first round, Memphis was first, Nashville was second and Knoxville was third. With Chattanooga eliminated and its votes redistributed, the second round finds Memphis still in first place, followed by Knoxville in second and Nashville has moved down to third place. No city yet has secured a majority of votes, so we move to the third round with the elimination of Nashville, and it becomes a contest between Memphis and Knoxville.

As in the second round with Chattanooga, all of the ballots currently counting for Nashville are added to the totals of Memphis or Knoxville based on which city is ranked next on that ballot. In this example the second-choice of the Nashville voters is Chattanooga, which is already eliminated. Therefore, the votes are added to their third-choice: Knoxville.

The third round of tabulation yields the following result:

| Votes in round/ City Choice | 1st | 2nd | 3rd |

|---|---|---|---|

| Memphis | 42% | 42% | 42% |

| Nashville | 26% | 26% | |

| Knoxville | 17% | 32% | 58% |

| Chattanooga | 15% |

Result: Knoxville, which was running third in the first tabulation, has moved up from behind to take first place in the third and final round. The winner of the election is Knoxville. However, if 6% of voters in Memphis were to put Nashville first, the winner would be Nashville, a preferable outcome for voters in Memphis. This is an example of potential tactical voting, though one that would be difficult for voters to carry out in practice. Also, if 17% of voters in Memphis were to stay away from voting, the winner would be Nashville. This is an example of IRV failing the participation criterion.

For comparison, note that traditional first-past-the-post voting would elect Memphis, even though most citizens consider it the worst choice, because 42% is larger than any other single city. As Nashville is a Condorcet winner, Condorcet methods would elect Nashville. A two-round method would have a runoff between Memphis and Nashville where Nashville would win, too.

2006 Burlington mayoral election

| Candidate | Round 1 | Round 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bob Kiss | 3,809 | (38.9%) | 4,761 | (48.6%) |

| Hinda Miller | 3,106 | (31.7%) | 3,986 | (40.7%) |

| Kevin Curley | 2,609 | (26.7%) | — | |

| Other | 254 | (2.6%) | — | |

| Exhausted ballots | 10 | (0.1%) | 1,041 | (10.5%) |

| Total | 9,778 | (100%) | 9,778 | (100%) |

In 2006, the U.S. city of Burlington, Vermont, held a mayoral election using instant-runoff voting. Progressive Bob Kiss won in two rounds. He won a majority of the vote among voters who ranked either him or Democrat Hinda Miller and 48.6% of those who participated in the first round. Miller earned 40.7% of first round voters, while 10.6% (1,031) of first round voters (largely backers of Republican candidate Kevin Curley) offered no preference between Miller and Kiss.[24]

After the first round, all but the top two candidates were eliminated, as their combined vote total (2,863) was less than Miller's, so that none could pull ahead of Miller, even by receiving every vote from the other minor candidates. The votes for these eliminated candidates were added to the totals of Kiss and Miller based on which one was ranked next on each ballot. After the second round count, Kiss was declared the winner as he had obtained a majority (54.4%) of the remaining unexhausted ballots.

1990 Irish presidential election

| Irish presidential election, 1990[25] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Candidate | Round 1 | Round 2 | ||

| Mary Robinson | 612,265 | (38.9%) | 817,830 | (51.6%) |

| Brian Lenihan | 694,484 | (43.8%) | 731,273 | (46.2%) |

| Austin Currie | 267,902 | (16.9%) | — | |

| Exhausted ballots | 9,444 | (0.6%) | 34,992 | (2.2%) |

| Total | 1,584,095 | (100%) | 1,584,095 | (100%) |

The result of the 1990 Irish presidential election provides an example of how instant-runoff voting can produce a different result from first-past-the-post voting. The three candidates were Brian Lenihan of the traditionally dominant Fianna Fáil party, Austin Currie of Fine Gael, and Mary Robinson, nominated by the Labour Party and the Worker's Party. After the first round, Lenihan had the largest share of the first-choice rankings (and hence would have won a first-past-the-post vote), but no candidate attained the necessary majority. Currie was eliminated and his votes reassigned to the next choice ranked on each ballot; in this process, Robinson received 82% of Currie's votes, thereby overtaking Lenihan.

Voting method criteria

Scholars rate voting methods using mathematically-derived voting method criteria, which describe desirable features of a method. No ranked-preference method can meet all of the criteria, because some of them are mutually exclusive, as shown by statements such as Arrow's impossibility theorem and the Gibbard–Satterthwaite theorem.

Many of the mathematical criteria by which voting methods are compared were formulated for voters with ordinal preferences. If voters vote according to the same ordinal preferences in both rounds, criteria can be applied to two-round systems of runoffs, and in that case, each of the criteria failed by IRV is also failed by the two-round system as they relate to automatic elimination of trailing candidates. Partial results exist for other models of voter behavior in the two-round method: see the two-round system article's criterion compliance section for more information.

The criteria that IRV meets, and those that it does not, are listed below.

Majority criterion The majority criterion states that "if one candidate is preferred by an absolute majority of voters, then that candidate must win". IRV meets this criterion.

Mutual majority criterion The mutual majority criterion states that "if an absolute majority of voters prefer every member of a group of candidates to every candidate not in that group, then one of the preferred group must win". IRV meets this criterion.

Later-no-harm criterion The later-no-harm criterion states that "if a voter alters the order of candidates lower in his/her preference (e.g. swapping the second and third preferences), then that does not affect the chances of the most preferred candidate being elected". IRV meets this criterion.

Resolvability criterion The resolvability criterion states that "the probability of an exact tie must diminish as more votes are cast". IRV meets this criterion.

Condorcet winner criterion The Condorcet winner criterion states that "if a candidate would win a head-to-head competition against every other candidate, then that candidate must win the overall election". It is incompatible with the later-no-harm criterion, so IRV does not meet this criterion.

IRV is more likely to elect the Condorcet winner than plurality voting and traditional runoff elections. The California cities of Oakland, San Francisco and San Leandro in 2010 provide an example; there were a total of four elections in which the plurality voting leader in first choice rankings was defeated, and in each case the IRV winner was the Condorcet winner, including a San Francisco election in which the IRV winner was in third place in first choice rankings.[26]

Condorcet loser criterion The Condorcet loser criterion states that "if a candidate would lose a head-to-head competition against every other candidate, then that candidate must not win the overall election". IRV meets this criterion.

Consistency criterion The consistency criterion states that if dividing the electorate into two groups and running the same election separately with each group returns the same result for both groups, then the election over the whole electorate should return this result. IRV, like all preferential voting methods which are not positional, does not meet this criterion.

Monotonicity criterion

The monotonicity criterion states that "a voter can't harm a candidate's chances of winning by voting that candidate higher, or help a candidate by voting that candidate lower, while keeping the relative order of all the other candidates equal." IRV does not meet this criterion. Allard[27] claims failure is unlikely, at a less than 0.03% chance per election. Some critics[28] argue in turn that Allard's calculations are wrong and the probability of monotonicity failure is much greater, at 14.5% under the impartial culture election model in the three-candidate case, or 7–10% in the case of a left-right spectrum. Lepelley et al. find a 2%–5% probability of monotonicity failure under the same election model as Allard.[29]

Participation criterion The participation criterion states that "the best way to help a candidate win must not be to abstain".[30] IRV does not meet this criterion: in some cases, the voter's preferred candidate can be best helped if the voter does not vote at all.[31] Depankar Ray finds a 50% probability that, when IRV elects a different candidate than Plurality, some voters would have been better off not showing up.[32]

Reversal symmetry criterion The reversal symmetry criterion states that "if candidate A is the unique winner, and each voter's individual preferences are inverted, then A must not be elected". IRV does not meet this criterion: it is possible to construct an election where reversing the order of every ballot paper does not alter the final winner.[31]

Independence of irrelevant alternatives criterion The independence of irrelevant alternatives criterion states that "the election outcome remains the same even if a candidate who cannot win decides to run." IRV does not meet this criterion; in the general case, instant-runoff voting can be susceptible to strategic nomination: whether or not a candidate decides to run at all can affect the result even if the new candidate cannot themselves win.[33] This is much less likely to happen than under plurality.

Independence of clones criterion The independence of clones criterion states that "the election outcome remains the same even if an identical candidate who is equally preferred decides to run." IRV meets this criterion.[34]

Comparison to other voting methods

Comparison of mechanics

Instant-runoff voting is one of many ranked ballot methods. For example, the elimination of the candidate with the most last-place rankings, rather than the one with the fewest first-place rankings, is called Coombs' method, and universal assignment of numerical values to each rank is used in the Borda count method. A chart in the article on the Schulze method compares various ranked ballot methods.

Comparison to first-past-the-post

At the Australian federal election for 2013, in September 2013, 135 out of the 150 House of Representatives seats (or 90 percent) were won by the candidate who led on first preferences. The other 15 seats (10 percent) were won by the candidate who placed second on first preferences.[35]

Resistance to tactical voting

The Gibbard–Satterthwaite theorem demonstrates that no (deterministic, non-dictatorial) voting method using only the preference rankings of the voters can be entirely immune from tactical voting. This implies that IRV is susceptible to tactical voting in some circumstances.

Scholarly research conclude that IRV is one of the less-manipulable voting methods, with theorist Nicolaus Tideman noting that, "alternative vote is quite resistant to strategy"[36] and Australian political analyst Antony Green dismissing suggestions of tactical voting.[37] James Green-Armytage tested four ranked-choice methods, and found the alternative vote to be the second-most-resistant to tactical voting, though it was beaten by a class of AV-Condorcet hybrids, and did not resist strategic withdrawal by candidates well.[38] Some simulations of several classes of voting methods in non-scholarly publications found IRV performed as badly as plurality when voters are strategic and fully informed about other voter's full preferences, and was out-performed by Range, Approval, and Borda.[39]

By not meeting the monotonicity, Condorcet winner, and participation criteria, IRV permits forms of tactical voting when voters have sufficient information about other voters' preferences, such as from accurate pre-election polling.[40] FairVote mentions that monotonicity failure can lead to situations where "Having more voters rank [a] candidate first, can cause [them] to switch from being a winner to being a loser."[41] That assessment is accurate, although it only happens in particular situations. The change in lower candidates is important: whether votes are shifted to the leading candidate, shifted to a fringe candidate, or discarded altogether is of no importance.

Tactical voting in IRV seeks to alter the order of eliminations in early rounds, to ensure that the original winner is challenged by a stronger opponent in the final round. For example, in a three-party election where voters for both the left and right prefer the centrist candidate to stop the "enemy" candidate winning, those voters who care more about defeating the "enemy" than electing their own candidate may cast a tactical first preference vote for the centrist candidate.

The 2009 mayoral election in Burlington, Vermont provides an example in which strategy theoretically could have worked but would have been unlikely in practice. In that election, most supporters of the candidate who came in second (a Republican who led in first choices) preferred the Condorcet winner, a Democrat, to the IRV winner, the Progressive Party nominee. If 371 (12.6%) out of the 2951 backers of the Republican candidate (those who also preferred the Democrat over the Progressive candidate for mayor) had insincerely raised the Democrat from their second choice to their first (not changing their rankings relative to their least favorite candidate, the IRV winner), the Democrat would then advance to the final round (instead of their favorite), defeated any opponent, and have won the IRV election.[40] This is an example of potential voter regret in that these voters who sincerely ranked their favorite candidate as first, find out after the fact that they caused the election of their least favorite candidate, which can lead to the voting tactic of compromising. Yet because the Republican led in first choices and only narrowly lost the final instant runoff, his backers would have been highly unlikely to pursue such a strategy.

Spoiler effect

The spoiler effect is when a difference is made to the anticipated outcome of an election due to the presence on the ballot paper of a candidate who (predictably) will lose. Most often this is when two or more politically similar candidates divide the vote for the more popular end of the political spectrum. That is, each receives fewer votes than a single opponent on the unpopular end of the spectrum who is disliked by the majority of voters but who wins from the advantage that, on that unpopular side, he or she is unopposed.

Proponents of IRV claim that IRV eliminates the spoiler effect,[42][43][44][45] since IRV makes it safe to vote honestly for marginal parties: Under a plurality method, voters who sympathize most strongly with a marginal candidate are strongly encouraged to instead vote for a more popular candidate who shares some of the same principles, since that candidate has a much greater chance of being elected and a vote for the marginal candidate will not result the marginal candidate's election. An IRV method reduces this problem, since the voter can rank the marginal candidate first and the mainstream candidate second; in the likely event that the fringe candidate is eliminated, the vote is not wasted but is transferred to the second preference.

However, when the third party candidate is more competitive, they can still act as a spoiler under IRV,[46][47][48][49] by taking away first-choice votes from the more mainstream candidate until that candidate is eliminated, and then that candidate's second-choice votes helping a more-disliked candidate to win. In these scenarios, it would have been better for the third party voters if their candidate had not run at all (spoiler effect), or if they had voted dishonestly, ranking their favorite second rather than first (favorite betrayal).[50]

For example, in the 2009 Burlington, Vermont mayoral election, if the Republican candidate who lost in the final instant runoff had not run, the Democratic candidate would have defeated the winning Progressive candidate. In that sense, the Republican candidate was a spoiler even though leading in first choice support.[40][51]

In practice, IRV does not seem to discourage candidacies. In Australia's House of Representatives elections in 2007, for example, the average number of candidates in a district was seven, and at least four candidates ran in every district; notwithstanding the fact that Australia only has two major political parties. Every seat was won with a majority of the vote, including several where results would have been different under plurality voting.[52] A study of ballot image data found that all of the 138 RCV elections held in four Bay Area cities in California elected the Condorcet winner, including many with large fields of candidates and 46 where multiple rounds of counting were required to determine a winner.[53]

Proportionality

IRV is not a proportional voting method. Like all winner-take-all voting methods, IRV tends to exaggerate the number of seats won by the largest parties; small parties without majority support in any given constituency are unlikely to earn seats in a legislature, although their supporters will be more likely to be part of the final choice between the two strongest candidates.[54] A simulation of IRV in the 2010 UK general election by the Electoral Reform Society concluded that the election would have altered the balance of seats among the three main parties, but the number of seats won by minor parties would have remained unchanged.[55]

Australia, a nation with a long record of using IRV for the election of legislative bodies, has had representation in its parliament broadly similar to that expected by plurality methods. Medium-sized parties, such as the National Party of Australia, can co-exist with coalition partners such as the Liberal Party of Australia, and can compete against it without fear of losing seats to other parties due to vote splitting.[56] IRV is more likely to result in legislatures where no single party has an absolute majority of seats (a hung parliament), but does not generally produce as fragmented a legislature as a fully proportional method, such as is used for the House of Representatives of the Netherlands or the New Zealand House of Representatives, where coalitions of numerous small parties are needed for a majority.

Costs

The costs of printing and counting ballot papers for an IRV election are no different from those of any other method using the same technology. However, the more-complicated counting system may encourage officials to introduce more advanced technology, such as software counters or electronic voting machines. Pierce County, Washington election officials outlined one-time costs of $857,000 to implement IRV for its elections in 2008, covering software and equipment, voter education and testing.[57]

Because it does not require two separate votes, IRV is assumed to cost less than two-round primary/general or general/runoff election methods.[58] However, in 2009, the auditor of Washington counties reported that the ongoing costs of the system were not necessarily balanced by the costs of eliminating runoffs for most county offices, because those elections may be needed for other offices not elected by IRV.[59] Other jurisdictions have reported immediate cost savings.[22]

Australian elections are counted by hand. The 2010 federal election cost a total of $7.68 per elector of which only a small proportion is the actual counting of votes.[18] Counting is now normally performed in a single pass at the polling center as described above.

The perceived costs or cost savings of adopting an IRV method are commonly used by both supporters and critics. In the 2011 referendum on the Alternative Vote in the UK, the NOtoAV campaign was launched with a claim that adopting the method would cost £250 million; commentators argued that this headline figure had been inflated by including £82 million for the cost of the referendum itself, and a further £130 million on the assumption that the UK would need to introduce electronic voting systems, when ministers had confirmed that there was no intention of implementing such technology, whatever the outcome of the election.[60] Automated vote counting is seen by some to have a greater potential for election fraud;[61] IRV supporters counter these claims with recommended audit procedures,[62] or note that automated counting is not required for the method at all.

Negative campaigning

John Russo, Oakland City Attorney, argued in the Oakland Tribune on 24 July 2006 that "Instant runoff voting is an antidote to the disease of negative campaigning. IRV led to San Francisco candidates campaigning more cooperatively. Under the method, their candidates were less likely to engage in negative campaigning because such tactics would risk alienating the voters who support 'attacked' candidates", reducing the chance that they would support the attacker as a second or third choice.[63][64]

In 2013–2014, the Rutgers-Eagleton Poll surveyed more than 4,800 likely voters in 21 cities after their local city elections—half in cities with IRV elections and 14 in control cities selected by project leaders Caroline Tolbert of the University of Iowa and Todd Donovan of Western Washington University. Among findings, respondents in IRV cities reported candidates spent less time criticizing opponents than in cities that did not use IRV. In the 2013 survey, for example, 5% of respondents said that candidates criticized each other "a great deal of the time" as opposed to 25% in non-IRV cities. An accompanying survey of candidates reported similar findings.[65]

Internationally, Benjamin Reilly suggests instant-runoff voting eases ethnic conflict in divided societies.[66] This feature was a leading argument for why Papua New Guinea adopted instant-runoff voting.[67] However, Lord Alexander's objections to the conclusions of the British Independent Commission on the Voting System's report[68] cites the example of Australia saying "their politicians tend to be, if anything, more blunt and outspoken than our own".

Plural voting

In Ann Arbor, Michigan arguments over IRV in letters to newspapers included the belief that IRV "gives minority candidate voters two votes", because some voters' ballots may count for their first choice in the first round and a lesser choice in a later round.[69] The argument that IRV represents plural voting is sometimes used in arguments over the "fairness" of the method, and has led to several legal challenges in the United States. The argument was addressed and rejected by a Michigan court in 1975; in Stephenson v. the Ann Arbor Board of City Canvassers, the court held "majority preferential voting" (as IRV was then known) to be in compliance with the Michigan and United States constitutions, writing:[70]

Under the "M.P.V. System", however, no one person or voter has more than one effective vote for one office. No voter's vote can be counted more than once for the same candidate. In the final analysis, no voter is given greater weight in his or her vote over the vote of another voter, although to understand this does require a conceptual understanding of how the effect of a "M.P.V. System" is like that of a run-off election. The form of majority preferential voting employed in the City of Ann Arbor's election of its Mayor does not violate the one-man, one-vote mandate nor does it deprive anyone of equal protection rights under the Michigan or United States Constitutions.

Invalid ballots and exhausted ballots

Because the ballot marking is more complex, there can be an increase in spoiled ballots. In Australia, voters are required to write a number beside every candidate, and error rates can be five times higher than plurality voting elections[71] Since Australia has compulsory voting, however, it is difficult to tell how many ballots are deliberately spoiled.[72] Most jurisdictions with IRV do not require complete rankings and may use columns to indicate preference instead of numbers. In American elections with IRV, more than 99% of voters typically cast a valid ballot.[73]

A 2015 study of four local U.S. elections that used IRV found that ballot exhaustion occurred often enough in each of them that the winner of each election did not receive a majority of votes cast in the first round. The rate of ballot exhaustion in each election ranged from a low of 9.6% to a high of 27.1%.[74] As one point of comparison, the number of votes cast in the 190 regularly scheduled primary runoff elections for the U.S House and U.S. Senate from 1994 to 2016 decreased from the initial primary on average by 39%, according to a 2016 study by FairVote.[75]

Robert's Rules of Order

The sequential elimination method used by IRV is described in Robert's Rules of Order Newly Revised[4] as an example of "preferential voting", a term covering "any of a number of voting methods by which, on a single ballot when there are more than two possible choices, the second or less-preferred choices of voters can be taken into account if no candidate or proposition attains a majority. While it is more complicated than other methods of voting in common use, and is not a substitute for the normal procedure of repeated balloting until a majority is obtained, preferential voting is especially useful and fair in an election by mail if it is impractical to take more than one ballot. In such cases, it makes possible a more representative result than under a rule that a plurality shall elect ... Preferential voting has many variations. One method is described ... by way of illustration."[76] And then the instant runoff voting method is detailed.[77]

Robert's Rules continues: "The system of preferential voting just described should not be used in cases where it is possible to follow the normal procedure of repeated balloting until one candidate or proposition attains a majority. Although this type of preferential ballot is preferable to an election by plurality, it affords less freedom of choice than repeated balloting, because it denies voters the opportunity of basing their second or lesser choices on the results of earlier ballots, and because the candidate or proposition in last place is automatically eliminated and may thus be prevented from becoming a compromise choice."[78] Two other books on parliamentary procedure take a similar stance, disapproving of plurality voting and describing preferential voting as an option, if authorized in the bylaws, when repeated balloting is impractical: The Standard Code of Parliamentary Procedure[79] and Riddick's Rules of Procedure.[80]

Global use

Australia

Instant-runoff voting has been used to elect members of the Australian House of Representatives since the 1919 federal election, where it was implemented by the Hughes Government. The Australian Senate uses a modified form, combining it with a proportional representation method. Counting of the paper ballot papers proceeds and when no candidate receives 50% plus one vote of the 1st preference vote (candidates with a number 1), the candidate with the least number of 1st preference votes is eliminated and that candidate's votes are distributed to the 2nd preferred candidate. The process continues until a candidate accumulates 50% plus 1 vote, or a simple majority. Counting will continue to finality, which results in what is referred to as the two-party preferred vote, which expresses the electorate's voting preference equivalent to a 2-person election of the 2 most popular candidates. A normal Federal Senate election see 6 Senators elected from each of the 6 States (plus one from the Federal Territories of the Northern Territory and the Australian Capital territory). To win a Senate seat candidates must accumulate a quota of the votes according to a formula.[1] Most state and council (local government) elections also use the method.

Canada

Also called the Alternative Vote in Canada,[81] IRV has never been used for federal elections but was used for provincial elections in British Columbia (1952 and 1953), Alberta (1926), and Manitoba (1927–1953).[82]

IRV is used in whole or in part to elect the leaders of the three largest federal political parties in Canada, the Liberal Party of Canada,[83] the Conservative Party of Canada, and the New Democratic Party of Canada, albeit the New Democratic Party uses a mixture of IRV and exhaustive voting, depending on the member. Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper won an IRV election to become party leader in the 2004 leadership election. In 2013, the Liberal Party of Canada membership elected Justin Trudeau as party leader through IRV in a national leadership election.[84] In the 2017 Conservative Party of Canada leadership election, the party membership used IRV with weighted voting to elect Andrew Scheer as party leader.

The province of Ontario has announced that they will allow municipalities the option to use instant-runoff voting for local elections starting in 2018.[85]

Czech Republic

IRV is used to elect leaders of the Green party.[86]

Hong Kong

IRV is used to elect a small number of functional constituencies of the Legislative Council, all of which have very small electorates.

India

IRV is used in numerous electoral college environments, including the election of the President of India by the members of the Parliament of India and of the Vidhan Sabhas – the state legislatures.[87]

Ireland

While most elections in the Republic of Ireland use the single transferable vote (STV),[88] in single-winner contests this reduces to IRV.[89] This is the case in all Presidential elections[89] and Seanad panel by-elections,[90] and most Dáil by-elections[89] In the rare event of multiple simultaneous vacancies in a single Dáil constituency, a single STV by-election may be held;[91] for Seanad panels, multiple IRV by-elections are held.[90]

New Zealand

IRV is used in the elections of mayors and councillors in single-member wards in some New Zealand cities, such as Dunedin and Wellington. Multi-member wards in these cities use STV.[92]

IRV, under the name Alternative Vote, was one of the four alternative methods available (alongside MMP, STV and SM) in the 1992 referendum on the voting method to elect MP's to the New Zealand House of Representatives. It came third of the alternative methods (ahead of SM) with 6.6% of the vote. IRV, under the name Preferential Vote, was one of the four alternative methods choices presented in the 2011 voting method referendum, but the referendum resulted in New Zealanders choosing to keep their proportional method of representation instead, while IRV came last with 8.34%.

IRV (again under the name Preferential Vote[93]) was used on the initial ballot of the 2015–2016 New Zealand flag referendums for voters to rank their preferences about the five new flag options.

Papua New Guinea

Since 2003, the national parliament of Papua New Guinea has been elected using an IRV variant called Limited Preferential Voting, where voters are limited to ranking three candidates.[94][95]

United Kingdom

In the United Kingdom the method is commonly known as the alternative vote. It is used to elect the leaders of the Labour Party and the Liberal Democrats. (The leader of the Conservative Party is elected under a similar method, a variant of the exhaustive ballot.) It is also used for by-elections to the British House of Lords, in which hereditary peers are selected for that body.[96] AV is also used by members of parliament to elect the chairmen of select committees and the Speaker of the House of Lords. The Speaker of the House of Commons is elected by the exhaustive ballot.

In 2010, the Conservative—Liberal Democrat coalition government agreed to hold a national referendum on the alternative vote,[97] held on 5 May 2011.[98] The proposal would have affected the way in which Members of Parliament are elected to the British House of Commons at Westminster. The result of the referendum was a vote against adoption of the alternative vote by a margin of 67.9 percent to 32.1 percent.[99]

United States

IRV is used by several municipalities and other jurisdictions in the United States, including San Francisco[100] and Oakland, California,[101] and Minneapolis and Saint Paul, Minnesota.[100] United States private associations that use IRV[102] include the Hugo Awards for science fiction,[103] the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in selection of the Oscar for Best Picture,[104] and more than fifty colleges and universities for student elections.[105] Starting with its 2018 elections, Maine was expected to become the first state to use instant-runoff voting for its primary and general elections for governor, U.S. Senate, U.S. House and state legislature, but the Maine Supreme Judicial Court said that the voting system violated the state constitution.[106][107]

Similar methods

Runoff voting

The term instant runoff voting is derived from the name of a class of voting methods called runoff voting. In runoff voting voters do not rank candidates in order of preference on a single ballot. Instead a similar effect is achieved by using multiple rounds of voting. All multi-round runoff voting methods allow voters to change their preferences in each round, incorporating the results of the prior round to influence their decision. This is not possible in IRV, as participants vote only once, and this prohibits certain forms of tactical voting that can be prevalent in 'standard' runoff voting.

Exhaustive ballot

A method closer to IRV is the exhaustive ballot. In this method—one familiar to fans of the television show American Idol—one candidate is eliminated after each round, and many rounds of voting are used, rather than just two.[108] Because holding many rounds of voting on separate days is generally expensive, the exhaustive ballot is not used for large-scale, public elections.

Two-round methods

The simplest form of runoff voting is the two-round system, which typically excludes all but two candidates after the first round, rather than gradually eliminating candidates over a series of rounds. Eliminations can occur with or without allowing and applying preference votes to choose the final two candidates. A second round of voting or counting is only necessary if no candidate receives an overall majority of votes. This method is used in Mali, France and the Finnish presidential election.

Contingent vote

The contingent vote, also known as Top-two IRV, or batch-style, is the same as IRV except that if no candidate achieves a majority in the first round of counting, all but the two candidates with the most votes are eliminated, and the second preferences for those ballots are counted. As in IRV, there is only one round of voting.

Under a variant of contingent voting used in Sri Lanka, and the elections for Mayor of London in the United Kingdom, voters rank a specified maximum number of candidates. In London, the Supplementary Vote allows voters to express first and second preferences only. Sri Lankan voters rank up to three candidates for the President of Sri Lanka.

While similar to "sequential-elimination" IRV, top-two can produce different results. Excluding more than one candidate after the first count might eliminate a candidate who would have won under sequential elimination IRV. Restricting voters to a maximum number of preferences is more likely to exhaust ballots if voters do not anticipate which candidates will finish in the top two. This can encourage voters to vote more tactically, by ranking at least one candidate they think is likely to win.

Conversely, a practical benefit of 'contingent voting' is expediency and confidence in the result with only two rounds. Particularly in elections with few (e.g., fewer than 100) voters, numerous ties can destroy confidence. Heavy use of tie-breaking rules leaves uncomfortable doubts over whether the winner might have changed if a recount had been performed.

Larger runoff process

IRV may also be part of a larger runoff process:

- Some jurisdictions that hold runoff elections allow absentee (only) voters to submit IRV ballots, because the interval between votes is too short for a second round of absentee voting. IRV ballots enable absentee votes to count in the second (general) election round if their first choice does not make the runoff. Arkansas, South Carolina and Springfield, Illinois adopt this approach.[109] Louisiana uses it only for members of the United States Service or who reside overseas.[110]

- IRV can quickly eliminate weak candidates in early rounds of an exhaustive ballot runoff, using rules to leave the desired number of candidates for further balloting.

- IRV allows an arbitrary victory threshold in a single round of voting, e.g., 60%. In such cases a second vote may be held to confirm the winner.[111]

- IRV elections that require a majority of cast ballots but not that voters rank all candidates may require more than a single IRV ballot due to exhausted ballots.

- Robert's Rules recommends preferential voting for elections by mail and requiring a majority of cast votes to elect a winner, giving IRV as their example. For in-person elections, they recommend repeated balloting until one candidate receives an absolute majority of all votes cast. Repeated voting allows voters to turn to a candidate as a compromise who polled poorly in the initial election.[4]

The common feature of these IRV variations is that one vote is counted per ballot per round, with rules that eliminate the weakest candidate(s) in successive rounds. Most IRV implementations drop the "majority of cast ballots" requirement.[112]

See also

- Alternative Vote Plus (AV+) or Alternative Vote Top-up proposed by the Jenkins Commission (UK)

- First-past-the-post voting

- None of the above (NOTA) or Re-Open Nominations (RON)

- Outline of democracy

- Single transferable vote, AV method for elections with multiple positions to be filled

References

- 1 2 "Australian Electoral Commission". Aec.gov.au. 2014-04-23. Retrieved 2014-04-30.

- ↑ "Ireland Constitution, Article 12(2.3)". International Constitutional Law. 1995. Retrieved 15 February 2008.

- ↑ Seely, Katharine Q. (2016-12-03). "Maine Adopts Ranked-Choice Voting. What Is It, and How Will It Work?". The New York Times. Retrieved 9 April 2017.

- 1 2 3 Robert, Henry (2011). Robert's Rules of Order Newly Revised (11th ed.). Da Capo Press. pp. 425–428. ISBN 978-0-306-82020-5.

- ↑ "Second Report: Election of a Speaker". House of Commons Select Committee on Procedure. 15 February 2001. Retrieved 18 February 2008.

- ↑ Cary, David (2011-01-01). "Estimating the Margin of Victory for Instant-runoff Voting". Proceedings of the 2011 Conference on Electronic Voting Technology/Workshop on Trustworthy Elections. EVT/WOTE'11. Berkeley, CA, USA: USENIX Association: 3–3.

- ↑ "The Alternative Vote: No Solution to the Democratic Deficit" (PDF). Fair Vote Canada. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 April 2014. Retrieved 23 April 2014.

- ↑ "S.L. 2006-192". Ncleg.net. Retrieved 6 May 2010.

- ↑ "CITIZEN-TIMES: Capital Letters – Post details: No instant runoff in Hendersonville". Blogs.citizen-times.com. Retrieved 6 May 2010.

- ↑ "South Carolina General Assembly : 116th Session, 2005–2006". Scstatehouse.gov. Retrieved 2015-03-01.

- ↑ "Bill Information". Arkleg.state.ar.us. Retrieved 2015-01-28.

- ↑ "Electoral Systems". Electoral Council of Australia. Archived from the original on 9 March 2008. Retrieved 15 February 2008.

- ↑ "Ranked-Choice Voting". Registrar of Voters, Alameda County. Retrieved 2016-12-15.

This format allows a voter to select a first-choice candidate in the first column, a second-choice candidate in the second column, and a third-choice candidate in the third column.

- ↑ Benjamin Reilly. "The Global Spread of Preferential Voting: Australian Institutional Imperialism" (PDF). FairVote.org. Retrieved 17 April 2011.

- ↑ McLean, Iain (October 2002). "Australian electoral reform and two concepts of representation" (PDF). p. 11. Retrieved 22 February 2008.

- ↑ "Australian Electoral History: Voting Methods". Australianpolitics.com. Archived from the original on 19 March 2011. Retrieved 17 April 2011.

- ↑ "The Origin of Senate Group Ticket Voting, and it didn't come from the Major Parties".

- 1 2 26, corporateName=Australian Electoral Commission; address=Queen Victoria Terrace, Parkes ACT 2600; contact=13 23. "Electoral Pocketbook 2011 – 3 The electoral process".

- ↑ "Antony Green's Election Blog: How the Alternative Vote Works". Blogs.abc.net.au. 2011-02-20. Retrieved 2014-04-30.

- ↑ "Declaration of Robert Richie in Support of Petition for Writ of Mandate" (PDF). Archive.fairvote.org. Retrieved 2015-03-01.

- ↑ FairVote (2008-06-25). "Ranked Voting and Election Integrity". FairVote.org. Retrieved 2014-04-30.

- 1 2 "Wake County Answers on IRV Election Administration". FairVote. Retrieved 2014-04-30.

- ↑ "Maine Public Broadcasting Network, Maine News & Programming". Mpbn.net. Archived from the original on 19 March 2014. Retrieved 2014-04-30.

- ↑ "2006 Burlington mayoral election". Voting Solutions. 7 March 2006. Retrieved 22 February 2008.

- ↑ "Presidential Election November 1990". ElectionsIreland.org. Retrieved 23 November 2009.

- ↑ FairVote. "Understanding the RCV Election Results in District 10". FairVote.org. Archived from the original on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 17 April 2011.

- ↑ Crispin Allard (January 1996). "Estimating the Probability of Monotonicity Failure in a UK General Election". Retrieved 4 May 2011.

- ↑ Warren D. Smith. "Monotonicity and Instant Runoff Voting". Retrieved 4 May 2011.

- ↑ Lepelley, Dominique; Chantreuil, Frederic; Berg, Sven (1996). "The likelihood of monotonicity paradoxes in run-off elections". Mathematical Social Sciences. 31 (3): 133–146. doi:10.1016/0165-4896(95)00804-7.

- ↑ More precisely, submitting a ballot that ranks A ahead of B should never change the winner from A to B.

- 1 2 Smith, Warren D. "Lecture 'Mathematics and Democracy'". Retrieved 12 May 2011.

- ↑ Ray, Depankar. "On the practical possibility of a 'no show paradox' under the single transferable vote". Mathematical Social Sciences. 11 (2): 183–189. doi:10.1016/0165-4896(86)90024-7.

- ↑ "Burlington Vermont 2009 IRV mayoral election". RangeVoting.org. Retrieved 17 April 2011.

- ↑ Green-Armytage, James (2004). "A Survey of Basic Voting Methods". Archived from the original on 3 June 2013.

- ↑ Antony Green (8 September 2015). Preferences, Donkey Votes and the Canning By-Election – Antony Green's Election Blog (Australian Broadcasting Corporation). Retrieved 8 September 2015.

- ↑ Bartholdi III, John J.; Orlin, James B. (1991). "Single transferable vote resists strategic voting" (PDF). Social Choice and Welfare. 8 (4): 341–354. doi:10.1007/bf00183045.

- ↑ "How to Vote Guide". Antony Green's Election Blog. Retrieved 2017-01-29.

What is the best way to vote strategically? The best strategic vote is to number the candidates in the order you would like to see them elected. ... in electorate of more than 90,000 voters, and without perfect knowledge, such a strategy is not possible.

- ↑ Green-Armytage, James. "Four Condorcet-Hare Hybrid Methods for Single-Winner Elections" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 June 2013. Retrieved 31 May 2011.

- ↑ Poundstone, William (2008-02-05). Gaming the Vote: Why Elections Aren't Fair (and What We Can Do About It). Macmillan. p. 239. ISBN 978-0-8090-4893-9.

IRV can perform better than plurality voting provided there are many honest voters. (In the unlikely case that everyone votes strategically, the two methods are tied.)

- 1 2 3 Warren Smith (2009) "Burlington Vermont 2009 IRV mayor election; Thwarted-majority, non-monotonicity & other failures (oops)"

- ↑ "Monotonicity and IRV – Why the Monotonicity Criterion is of Little Import". Archive.fairvote.org. Retrieved 17 April 2011.

- ↑ "Instant Run-Off Voting". archive.fairvote.org. Retrieved 2017-01-29.

IRV removes the "spoiler effect" whereby minor party or independent candidates knock off major party candidates, increasing the choices available to the voters.

- ↑ "Cal IRV FAQ". www.cfer.org. Retrieved 2017-01-29.

IRV completely eliminates the 'spoiler' effect – that is, votes split between a weak and a strong candidate won't cause the strong candidate to lose if s/he is the second choice of the weak candidate's voters.

- ↑ "OP-ED | No More Spoilers? Instant Runoff Voting Makes Third Parties Viable, Improves Democracy | CT News Junkie". CT News Junkie. Retrieved 2017-04-20.

Instant-runoff voting ends the spoiler effect forever

- ↑ CGP Grey (2011-04-06), The Alternative Vote Explained, retrieved 2017-04-20

- ↑ "The Spoiler Effect". The Center for Election Science. 2015-05-20. Retrieved 2017-01-29.

- ↑ "The Problem with Instant Runoff Voting | minguo.info". minguo.info. Retrieved 2017-01-29.

After a minor party is strong enough to win, on the other hand, a vote for them could have the same spoiler effect that it could have under the current plurality system

- ↑ "Example to demonstrate how IRV leads to 'spoilers,' 2-party domination". RangeVoting.org. Retrieved 2017-01-29.

IRV means betraying your true favorite third party candidate pays off. Voting third party can mean wasting your vote under IRV, just like under plurality.

- ↑ The Center for Election Science (2013-12-02), Favorite Betrayal in Plurality and Instant Runoff Voting, retrieved 2017-01-29

- ↑ Comments. "The False Promise of Instant Runoff Voting". Cato Unbound. Retrieved 2017-01-29.

They'll have a strategic incentive to falsify their preferences.

- ↑ "2009 Burlington Mayor IRV Failure". bolson.org. Retrieved 2017-01-29.

- ↑ "House of Representatives Results". Results.aec.gov.au. Retrieved 2015-03-01.

- ↑ "Every RCV Election in the Bay Area So Far Has Produced Condorcet Winners". fairvote.org. Retrieved 2017-02-13.

- ↑ "Types of Voting Systems". Mtholyoke.edu. 8 April 2005. Retrieved 6 May 2010.

- ↑ Travis, Alan (10 May 2010). "Electoral reform: Alternative vote system would have had minimal impact on outcome of general election". London: The Guardian. Retrieved 1 April 2011.

- ↑ History of Preferential Voting in Australia, Australian Broadcasting Corporation, 2004 Election Guide. "Such a long lasting Coalition would not have been possible under first part the post voting"

- ↑ "Pierce County RCV Overview – City of LA Briefing" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 6 May 2010.

- ↑ Archived 18 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "County auditor sees savings from scrapping ranked choice voting". Blogs.thenewstribune.com. 30 August 2006. Retrieved 6 May 2010.

- ↑ "No to AV campaign reject rivals' 'scare stories' claim". Bbc.co.uk. 24 February 2011. Retrieved 17 April 2011.

- ↑ "Nc Voter". Nc Voter. Retrieved 6 May 2010.

- ↑ "Ranked Choice Voting and Election Integrity". FairVote. 25 June 2008. Retrieved 6 May 2010.

- ↑ Murphy, Dean E. (30 September 2004). "New Runoff System in San Francisco Has the Rival Candidates Cooperating". The New York Times.

- ↑ Oakland Tribune, John Russo Archived 6 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Ranked Choice Voting in Practice: Candidate Civility in Ranked Choice Elecitons" (PDF). fairvote.org. FairVote. Retrieved 2 December 2015.

- ↑ "Project MUSE". Muse.jhu.edu. Retrieved 6 May 2010.

- ↑ "Papua New Guinea: Leaflet on Limited Preferential Voting System, Electoral Knowledge Network

- ↑ "Recommendations and Conclusions". The Report of the Independent Commission on the Voting System.

- ↑ Walter, Benjamin. "History of Preferential Voting in Ann Arbor". Archived from the original on 8 February 2012.

- ↑ "Ann Arbor Law Suit". FairVote. Retrieved 10 May 2011.

- ↑ "Busting the Myths of AV". No2av.org. 25 October 2010. Archived from the original on 8 February 2011. Retrieved 17 April 2011.

- ↑ "Informal Voting – Two Ways of Allowing More Votes to Count". ABC Elections. 28 February 2011. Retrieved 15 August 2011.

- ↑ "Instant Runoff Voting and Its Impact on Racial Minorities" (PDF). New America Foundation. 1 August 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 June 2011. Retrieved 15 August 2011.

- ↑ Burnett, Craig M.; Kogan, Vladimir (March 2015). "Ballot (and voter) 'exhaustion' under Instant Runoff Voting: An examination of four ranked-choice elections". Electoral Studies. 37: 41–49. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2014.11.006.

- ↑ https://fairvote.app.box.com/v/federalprimaryrunoffs2016

- ↑ Robert 2011, p. 426

- ↑ Robert 2011, pp. 426–428

- ↑ Robert 2011, p. 428

- ↑ Sturgis, Alice (2001). The Standard Code of Parliamentary Procedure, 4th ed.

- ↑ Riddick & Butcher (1985). Riddick's Rules of Procedure, 1985 ed.

- ↑ "Alternative voting of mixed-member proportional: What can we expect? Louis Massicotte, University of Montreal". Policy Options. July–August 2001. Archived from the original on 24 April 2014. Retrieved 23 April 2014.

- ↑ "The Political Consequences of the Alternative Vote: Lessons from Western Canada. Harold J. Jansen, University of Lethbridge". Canadian Journal of Political Science Vol. 37, Issue 03. pp 647–669. September 2004. Retrieved 23 April 2014.

- ↑ "Liberals vote overwhelmingly in favour of one-member, one-vote". Liberal.ca. 2 May 2009. Archived from the original on 4 May 2011. Retrieved 17 April 2011.

- ↑ "What Comes Next in the Liberal Vote". Maclean's. 5 April 2013. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- ↑ "Ranked ballot a priority for 2018 civic elections, Kathleen Wynne says". The Toronto Star. 30 Sep 2014. Retrieved 30 Sep 2014.

- ↑ Václav Novák (28 February 2013). "Zelení otestovali volební systém bez ztracených hlasů, který podporuje širokou shodu". data.blog.ihned.cz. Retrieved 30 December 2013.

- ↑ swapnil (29 October 2010). "IAS OUR DREAM: Presidents of India, Rashtrapati Bhavan, Trivia". Swapsushias.blogspot.com. Retrieved 3 December 2010.

- ↑ Franchise Section (February 2011). "Guide to Ireland's PR-STV Electoral System" (PDF). Department of the Environment, Heritage and Local Government. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2011. Retrieved 29 April 2011.

- 1 2 3 Muckerras, Malcolm; William Muley (1998). "Preferential Voting in Australia, Ireland and Malta" (PDF). Griffith Law Review. 7 (2): 225–248.

- 1 2 Seanad Electoral (Panel Members) Act, 1947 §58: Provision applicable where more than one casual vacancy. Irish Statute Book

- ↑ Electoral Act, 1992 §39(3) Irish Statute Book

- ↑ "Elections – 2007 Final Results". Wellington city council. 2007.

- ↑ "Referendums on the New Zealand Flag > Voting in the first referendum > How Preferential Voting works". www.elections.org.nz. New Zealand Electoral Commission. Retrieved 5 December 2015.

- ↑ "Center for Voting and Democracy". Archive.fairvote.org. Retrieved 17 April 2011.

- ↑ "Limited Preferential Voting" (PDF). Aceproject.org. Retrieved 3 October 2010.

- ↑ "Notice of Conservative Hereditary Peers' By-Election to the House of Lords" (PDF). House of Lords.

- ↑ "BBC's Q&A: The Conservative-Lib Dem coalition". BBC. 13 May 2010. Retrieved 3 October 2010.

- ↑ Norman Smith Chief political correspondent, BBC Radio 4 (2 July 2010). "Voting reform referendum planned for next May". BBC. Retrieved 3 October 2010.

- ↑ The Electoral Commission Referendum result

- 1 2 "Instant runoff voting exercises election judge fingers" Minnesota Public Radio, 10 May 2009

- ↑ "Oakland Rising:Instant Runoff Voting". oaklandrising.com. 2010. Archived from the original on 27 July 2011. Retrieved 23 December 2010.

- ↑ "Organizations & Corporations". FairVote. 17 March 2001. Retrieved 6 May 2010.

- ↑ "Oscars Copy Hugos". The Hugo Awards. Retrieved 6 May 2010.

- ↑ "Preferential Voting Extended to Best Picture on Final Ballot for 2009 Oscars". Oscars.org. Retrieved 6 May 2010.

- ↑ instantrunoff.com

- ↑ "Maine became the first state in the country Tuesday to pass ranked choice voting". 10 November 2016.

- ↑ "Opinion of the Justices of the Supreme Judicial Court". 23 May 2017.

- ↑ "Glossary: Exhaustive ballot". Securevote.com.au. Retrieved 6 May 2010.

- ↑ "Initiatives – Pew Center on the States" (PDF). Electionline.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 May 2008. Retrieved 6 May 2010.

- ↑ IRV for Louisiana's Overseas Voters (web page), FairVote IRV America, retrieved June 16, 2013

- ↑ For example, in 2006, the Independence Party of Minnesota used IRV for its endorsement elections, requiring 60% to win, and exhaustive balloting to follow if needed.

- ↑ Vermont S.22 1(c)3 Sec. 7. (6) ... if neither of the last two remaining candidates in an election ... received a majority, the report and the tabulations performed by the instant runoff count committee shall be forwarded to the Washington superior court, which shall issue a certificate of election to whichever of the two remaining candidates received the greatest number of votes at the conclusion of the instant runoff tabulation, and send a certified copy of the tabulation and results to the secretary of state.

External links

- 2010 articles from the Constitution Society and Electoral Reform Society summarizing the proposed change in the United Kingdom to IRV/Alternative Vote

Practice

- Advantages and disadvantages of AV from the ACE Project Electoral Design Reference Materials

- A Handbook of Electoral System Design from International IDEA

- Australian Electoral Commission Web Site

- Preferential Voting in Australia from Australian Politics.com

- San Francisco Department of Elections, California

- Alameda County Registrar of Voters, California

- City of Minneapolis, Minnesota

- Ranked Choice Voting Resource Center

Demos and simulations

- The Star Tribune: How ranked-choice voting works – an interactive graphic

- AmericanQuorum.com A ranked-choice ballot tool from the Indaba Application Network, including the animated display of an instant runoff.

- BBC: Would the alternative vote have changed history?, illustration of how the results of the last six general elections might have looked had the 'alternative vote' system been in place.

- OpenSTV – Open source software for computing IRV and STV

- Favourite Futurama Character Poll

- Voting System Visualizations – 2-dimensional plots of results of various methods, with assumptions of sincere voting behavior.

- Simulation Of Various Voting Models for Close Elections Opposition article by Brian Olson.

Advocacy groups and positions

- Yes to Fairer Votes campaign site for the Yes side of the United Kingdom Alternative Vote referendum, 2011

- Washington Post

- Ranked Choice Voting at FairVote

- League of Women Voters of Vermont

- Ranked Choice Voting at [Represent.Us]

- InstantRunoff.com

- Ranked Ballot Initiative of Toronto, rabit.ca

- Roosevelt Institution

- Citizens for Voter Choice :: Massachusetts

- FairVote Minnesota

- Common Cause Massachusetts

- Brookings Institution's "Empowering Moderate Voters" paper

- Does the Alternative Vote Bring Tyranny to Australia? – Antony Green ABC

Opposition groups and positions

- Fair Vote Canada paper on the Alternative Vote

- IRV page at the Center for Range Voting

- Instant Runoff Voting Report Values and Risks Report by the N.C. Coalition for Verified Voting