Toxicodendron radicans

| Poison ivy | |

|---|---|

| | |

| Poison ivy during autumn | |

| |

| Poison ivy in spring, Ottawa, Ontario | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| (unranked): | Angiosperms |

| (unranked): | Eudicots |

| (unranked): | Rosids |

| Order: | Sapindales |

| Family: | Anacardiaceae |

| Genus: | Toxicodendron |

| Species: | T. radicans |

| Binomial name | |

| Toxicodendron radicans (L.) Kuntze | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Toxicodendron radicans, commonly known as eastern poison ivy[1] or poison ivy, is a poisonous Asian and North American flowering plant that is well known for causing Urushiol-induced contact dermatitis, an itchy, irritating, and sometimes painful rash in most people who touch it. It is caused by urushiol, a clear liquid compound in the plant's sap.[2] The species is variable in its appearance and habit, and despite its common name it is not a true ivy (Hedera), but rather a member of the cashew and pistachio family. Toxicodendron radicans is commonly eaten by many animals, and the seeds are consumed by birds,[3] but poison ivy is most often thought of as an unwelcome weed.

Description

There are numerous subspecies and/or varieties of T. radicans,[4] which can be found growing in any of the following forms; all of which have woody stems:

- as a climbing vine that grows on trees or some other support

- as a shrub up to 1.2 metres (3 ft 11 in) tall

- as a trailing vine that is 10–25 centimetres (3.9–9.8 in) tall

- Subspecies and varieties[5]

- Toxicodendron radicans subsp. eximum (Greene) Gillis

- Toxicodendron radicans subsp. hispidum (Engl.) Gillis

- Toxicodendron radicans subsp. negundo (Greene) Gillis[6]

- Toxicodendron radicans var. negundo (Greene) Reveal

- Toxicodendron radicans var. pubens (Engelm. ex S. Watson) Reveal

- Toxicodendron radicans subsp. radicans

- Toxicodendron radicans var. radicans

- Toxicodendron radicans subsp. rydbergii (Small ex Rydb.) Á. Löve & D. Löve

- Toxicodendron radicans var. rydbergii (Small ex Rydb.) Erskine[7]

- Toxicodendron radicans subsp. verrucosum (Scheele) Gillis

The deciduous leaves of T. radicans are trifoliate with three almond-shaped leaflets.[8] Leaf color ranges from light green (usually the younger leaves) to dark green (mature leaves), turning bright red in fall; though other sources say leaves are reddish when expanding, turn green through maturity, then back to red, orange, or yellow in the fall. The leaflets of mature leaves are somewhat shiny. The leaflets are 3–12 cm (1.2–4.7 in) long, rarely up to 30 cm (12 in). Each leaflet has a few or no teeth along its edge, and the leaf surface is smooth. Leaflet clusters are alternate on the vine, and the plant has no thorns. Vines growing on the trunk of a tree become firmly attached through numerous aerial rootlets.[9] The vines develop adventitious roots, or the plant can spread from rhizomes or root crowns. The milky sap of poison ivy darkens after exposure to the air.

The urushiol compound in poison ivy is not a defensive measure; rather, it helps the plant to retain water. It is frequently eaten by animals such as deer and bears.[10]

Toxicodendron radicans spreads either vegetatively or sexually. It is dioecious; flowering occurs from May to July. The yellowish- or greenish-white flowers are typically inconspicuous and are located in clusters up to 8 cm (3.1 in) above the leaves. The berry-like fruit, a drupe, mature by August to November with a grayish-white colour.[8] Fruits are a favorite winter food of some birds and other animals. Seeds are spread mainly by animals and remain viable after passing through the digestive tract.

Toxicodendron radicans vine with typical reddish "hairs." Like the leaves, the vines are poisonous to humans.

Toxicodendron radicans vine with typical reddish "hairs." Like the leaves, the vines are poisonous to humans. Toxicodendron radicans in Perrot State Park, Trempealeau County, Wisconsin

Toxicodendron radicans in Perrot State Park, Trempealeau County, Wisconsin Flower detail, with bee

Flower detail, with bee Poison ivy on a roadside

Poison ivy on a roadside

Distribution and habitat

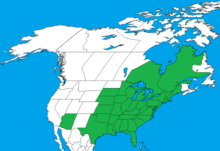

Toxicodendron radicans grows throughout much of North America, including the Canadian Maritime provinces, Quebec, Ontario, Manitoba, and all U.S. states east of the Rocky Mountains,[11] as well as in the mountainous areas of Mexico up to around 1,500 m (4,900 ft). Caquistle or caxuistle is the Nahuatl term for the species. It is normally found in wooded areas, especially along edge areas where the tree line breaks and allows sunshine to filter through. It also grows in exposed rocky areas, open fields and disturbed areas.

It may grow as a forest understory plant, although it is only somewhat shade-tolerant.[8] The plant is extremely common in suburban and exurban areas of New England, the Mid-Atlantic, and the Southeastern United States. The similar species T. diversilobum (western poison oak) and T. rydbergii (western poison ivy) are found in western North America.

Toxicodendron radicans rarely grows at altitudes above 1,500 m (4,900 ft), although the altitude limit varies in different locations.[8] The plants can grow as a shrub up to about 1.2 metres (3.9 ft) tall, as a groundcover 10–25 cm (3.9–9.8 in) high, or as a climbing vine on various supports. Older vines on substantial supports send out lateral branches that may be mistaken for tree limbs at first glance.

It grows in a wide variety of soil types, and soil pH from 6.0 (acidic) to 7.9 (moderately alkaline). It is not particularly sensitive to soil moisture, although it does not grow in desert or arid conditions. It can grow in areas subject to seasonal flooding or brackish water.[8]

It is more common now than when Europeans first arrived in North America. The development of real estate adjacent to wild, undeveloped land has engendered "edge effects", enabling poison ivy to form vast, lush colonies in these areas. It is listed as a noxious weed in the US states of Minnesota and Michigan and in the Canadian province of Ontario.

Outside North America, T. radicans is also found in the temperate parts of Asia, in Japan, Taiwan, the Russian islands of Sakhalin and the Kuriles, and in parts of China.[12]

A study by researchers at the University of Georgia found that poison ivy is particularly sensitive to carbon dioxide levels, greatly benefiting from higher concentrations in the atmosphere. Poison ivy's growth and potency has already doubled since the 1960s, and it could double again once carbon dioxide levels reach 560 ppm.[10]

Aids to identification

The following four characteristics are sufficient to identify poison ivy in most situations: (a) clusters of three leaflets, (b) alternate leaf arrangement, (c) lack of thorns, and (d) each group of three leaflets grows on its own stem, which connects to the main vine.

The appearance of poison ivy can vary greatly between environments, and even within a large area. Identification by experienced people is often made difficult by leaf damage, the plant's leafless condition during winter, and unusual growth forms due to environmental or genetic factors.

Various mnemonic rhymes describe the characteristic appearance of poison ivy:[13]

- "Leaflets three; let it be" is the best known and most useful cautionary rhyme. It applies to poison oak, as well as to poison ivy, but other, non-harmful plants have similar leaves.[14]

- "Hairy vine, no friend of mine."[15]

- "Berries white, run in fright" and "Berries white, danger in sight."[15]

Effects on the body

Urushiol-induced contact dermatitis is the allergic reaction caused by poison ivy. In extreme cases, a reaction can progress to anaphylaxis. Around 15% to 25% of people have no allergic reaction to urushiol, but most people will have a greater reaction with repeated or more concentrated exposure.[16][17]

Over 350,000 people are affected by poison ivy annually in the United States.[18]

The pentadecylcatechols of the oleoresin within the sap of poison ivy and related plants causes the allergic reaction; the plants produce a mixture of pentadecylcatechols, which collectively is called urushiol. After injury, the sap leaks to the surface of the plant where the urushiol becomes a blackish lacquer after contact with oxygen.[2][19]

Urushiol binds to the skin on contact, where it causes severe itching that develops into reddish inflammation or non-coloured bumps, and then blistering. These lesions may be treated with Calamine lotion, Burow's solution compresses, dedicated commercial poison ivy itch creams, or baths to relieve discomfort,[20] though recent studies have shown some traditional medicines to be ineffective.[21][22] Over-the-counter products to ease itching—or simply oatmeal baths and baking soda—are now recommended by dermatologists for the treatment of poison ivy.[23] A plant-based remedy cited to counter urushiol-induced contact dermatitis is jewelweed, and a jewelweed mash made from the living plant was effective in reducing poison ivy dermatitis, supporting ethnobotanical use, while jewelweed extracts had no positive effect in clinical studies.[24][25][26][27] Others argue that prevention of lesions is easy if one practices effective washing, using plain soap, scrubbing with a washcloth, and rinsing three times within two to eight hours of exposure.[28]

The oozing fluids released by scratching blisters do not spread the poison. The fluid in the blisters is produced by the body and it is not urushiol itself.[29] The appearance of a spreading rash indicates that some areas received more of the poison and reacted sooner than other areas or that contamination is still occurring from contact with objects to which the original poison was spread. Those affected can unknowingly spread the urushiol inside the house, on phones, door knobs, couches, counters, desks, and so on, thus in fact repeatedly coming into contact with poison ivy and extending the length of time of the rash. If this has happened, wipe down the surfaces with bleach or a commercial urushiol removal agent. The blisters and oozing result from blood vessels that develop gaps and leak fluid through the skin; if the skin is cooled, the vessels constrict and leak less.[30] If poison ivy is burned and the smoke then inhaled, this rash will appear on the lining of the lungs, causing extreme pain and possibly fatal respiratory difficulty.[31] If poison ivy is eaten, the mucus lining of the mouth and digestive tract can be damaged.[32] A poison ivy rash usually develops within a week of exposure and can last anywhere from one to four weeks, depending on severity and treatment. In rare cases, poison ivy reactions may require hospitalization.[33]

Urushiol oil can remain active for several years, so handling dead leaves or vines can cause a reaction. In addition, oil transferred from the plant to other objects (such as pet fur) can cause the rash if it comes into contact with the skin.[34][35] Clothing, tools, and other objects that have been exposed to the oil should be washed to prevent further transmission.

People who are sensitive to poison ivy can also experience a similar rash from mangoes. Mangoes are in the same family (Anacardiaceae) as poison ivy; the sap of the mango tree and skin of mangoes has a chemical compound similar to urushiol.[36] A related allergenic compound is present in the raw shells of cashews.[37] Similar reactions have been reported occasionally from contact with the related Fragrant Sumac (Rhus aromatica) and Japanese lacquer tree. These other plants are also in the Anacardiaceae family.

Treatment of poison ivy rash

Immediate washing with soap and cold water or rubbing alcohol may help prevent a reaction. Hot water should not be used, as it causes one's pores to open up and admit the oils from the plant.[38] During a reaction, calamine lotion or diphenhydramine may help mitigate symptoms. Corticosteroids, either applied to the skin or taken by mouth, may be appropriate in extreme cases. An astringent containing aluminum acetate (such as Burow's solution) may also provide relief and soothe the uncomfortable symptoms of the rash.[39]

"A wise old man told me that the water in a quench bucket (which is the bucket a blacksmith uses to cool iron rapidly by dunking the hot iron in it) was the best cure-all for poison ivy that he had ever used. When a friend came down with a bad case of poison ivy and told me that calamine lotion wasn't working, I shared the wise man's story. She promptly filled a plastic spray bottle with my dirty quench water and coated her arms and legs. A day later she returned to the shop wanting to sell the "magic elixir" to the public. The theory? Heavy concentrations of iron in the water accelerated the drying up of poison ivy blisters."[40]

By using a detergent, the urushoil can be emulsified to break it down so that it can be washed away more easily. Adding sand or a gritty substance to the detergent, will exfoliate the skin, taking the emulsified oil with it. Mix the abrasive with a dish washing liquid such as Dawn, and rubbing it briskly over the effected areas for several minutes, will mix the urushoil into the detergent, allowing it to be flushed away.

Similar-looking plants

- Virgin's bower (Clematis virginiana) (also known as Devil's Darning Needles, Devil's Hair, Love Vine, Traveller's Joy, Virginia Virgin's Bower, Wild Hops, and Woodbine; syn. Clematis virginiana L. var. missouriensis (Rydb.) Palmer & Steyermark [1]) is a vine of the Ranunculaceae family native to the United States. This plant is a vine that can climb up to 10–20 ft tall. It grows on the edges of the woods, moist slopes, and fence rows and in thickets and streambanks. It produces white, fragrant flowers about an inch in diameter between July and September.

- Box-elder (Acer negundo) saplings have leaves that can look very similar to those of poison ivy, although the symmetry of the plant itself is very different. While box-elders often have five or seven leaflets, three leaflets are also common, especially on smaller saplings. The two can be differentiated by observing the placement of the leaves where the leaf stalk meets the main branch (where the three leaflets are attached). Poison ivy has alternate leaves, which means the three-leaflet leaves alternate along the main branch. The maple (which the box-elder is a species of) has opposite leaves; another leaf stalk directly on the opposite side is characteristic of box-elder.

- Virginia creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia) vines can look like poison ivy. The younger leaves can consist of three leaflets but have a few more serrations along the leaf edge, and the leaf surface is somewhat wrinkled. However, most Virginia creeper leaves have five leaflets. Virginia creeper and poison ivy very often grow together, even on the same tree. Even those who do not get an allergic reaction to poison ivy may be allergic to the oxalate crystals in Virginia creeper sap.

- Western poison oak (Toxicodendron diversilobum) leaflets also come in threes on the end of a stem, but each leaflet is shaped somewhat like an oak leaf. Western poison oak grows only in the western United States and Canada, although many people will refer to poison ivy as poison oak. This is because poison ivy will grow in either the ivy-like form or the brushy oak-like form depending on the moisture and brightness of its environment. The ivy form likes shady areas with only a little sun, tends to climb the trunks of trees, and can spread rapidly along the ground.

- Poison sumac (Toxicodendron vernix) has compound leaves with 7–15 leaflets. Poison sumac never has only three leaflets.

- Kudzu (Pueraria lobata) is a non-toxic edible vine that scrambles extensively over lower vegetation or grows high into trees. Kudzu is an invasive species in the southern United States. Like poison ivy, it has three leaflets, but the leaflets are bigger than those of poison ivy and are pubescent underneath with hairy margins.

- Blackberries and raspberries (Rubus spp.) can resemble poison ivy, with which they may share territory; however, blackberries and raspberries almost always have thorns on their stems, whereas poison ivy stems are smooth. Also, the three-leaflet pattern of some blackberry and raspberry leaves changes as the plant grows: Leaves produced later in the season have five leaflets rather than three. Blackberries and raspberries have many fine teeth along the leaf edge, the top surface of their leaves is very wrinkled where the veins are, and the bottom of the leaves is light minty-greenish white. Poison ivy is all green. The stem of poison ivy is brown and cylindrical, while blackberry and raspberry stems can be green, can be squared in cross-section, and can have prickles. Raspberries and blackberries are never truly vines; that is, they do not attach to trees to support their stems.

- The thick vines of riverbank grape (Vitis riparia), with no rootlets visible, differ from the vines of poison ivy, which have so many rootlets that the stem going up a tree looks furry. Riverbank grape vines are purplish in colour, tend to hang away from their support trees, and have shreddy bark; poison ivy vines are brown, attached to their support trees, and do not have shreddy bark.

- Fragrant sumac (Rhus aromatica) has a very similar appearance to poison ivy. While both species have three leaflets, the center leaflet of poison ivy is on a long stalk, while the center leaflet of fragrant sumac does not have an obvious stalk. When crushed, fragrant sumac leaves have a fragrance similar to citrus while poison ivy has little or no distinct fragrance. Fragrant sumac produces flowers before the leaves in the spring, while poison ivy produces flowers after the leaves emerge. Flowers and fruits of fragrant sumac are at the end of the stem, but occur along the middle of the stem of poison ivy. Fragrant sumac fruit ripens to a deep reddish color and is covered with tiny hairs while poison ivy fruit is smooth and ripens to a whitish color.

- Hoptree (Ptelea trifoliata) has leaves that are remarkably similar. It is, however, a much larger plant so confusion is unlikely for any but the smallest specimens. The flowers and seeds are also easily distinguished from those of poison ivy.

Similar allergenic plants

- Toxicodendron rydbergii (Western poison ivy)

- Smodingium argutum (African poison ivy)

- Toxicodendron pubescens (Poison oak – Eastern)

- Toxicodendron diversilobum (Poison oak – Western)

- Toxicodendron vernix (Poison sumac)

- Gluta spp (Rengas tree)

- Toxicodendron vernicifluum (Japanese lacquer tree)

- Lithraea molleoides (Aruera - South America)

References

- ↑ "Toxicodendron radicans". Natural Resources Conservation Service PLANTS Database. USDA. Retrieved 11 December 2015.

- 1 2 Donald G. Barceloux (2008). Medical Toxicology of Natural Substances: Foods, Fungi, Medicinal Herbs, Plants, and Venomous Animals. John Wiley and Sons. pp. 681–. ISBN 978-0-471-72761-3. Retrieved 26 July 2010.

- ↑ Department of Biology Hamilton College Ernest H. Williams Jr. Professor (26 April 2005). The Nature Handbook: A Guide to Observing the Great Outdoors: A Guide to Observing the Great Outdoors. Oxford University Press. pp. 57–. ISBN 978-0-19-972075-0.

- ↑ Sally S. Weeks; Harmon P. Weeks, Jr. (1 January 2012). Shrubs and Woody Vines of Indiana and the Midwest: Identification, Wildlife Values, and Landscaping Use. Purdue University Press. pp. 356–. ISBN 978-1-55753-610-5.

- ↑ The Plant List, Toxicodendron radicans (L.) Kuntze

- ↑ "Tropicos – Name – Toxicodendron radicans subsp. negundo (Greene) Gillis". tropicos.org.

- ↑ "Toxicodendron radicans var. rydbergii (Small ex Rydberg) Erskine". canadensys.net.

- 1 2 3 4 5 USDA Fire Effects Information System: SPECIES: Toxicodendron radicans, T. rydbergii

- ↑ Petrides, George A. A Field Guide to Trees and Shrubs (Peterson Field Guides), Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1986, p. 130.

- 1 2 David Templeton (July 22, 2013). "Climate change is making poison ivy grow bigger and badder". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved July 23, 2013.

- ↑ Biota of North America Program 2014 county distribution map

- ↑ "Toxicodendron radicans – Distribution Range". www. ars-grin.gov. Retrieved 7 April 2013.

- ↑ "Poison Ivy Treatment Guide, Getting Rid of the Plants: Identifying Poison Ivy".

- ↑ Donald G. Crosby (2004). The Poisoned Weed: Plants Toxic to Skin. Oxford University Press. pp. 32–. ISBN 978-0-19-515548-8.

- 1 2 Neil L. Jennings (2010). In Plain Sight: Exploring the Natural Wonders of Southern Alberta. Rocky Mountain Books Ltd. pp. 105–. ISBN 978-1-897522-78-3.

- ↑ "How Poison Ivy Works". HowStuffWorks.

- ↑ Michael Rohde. "Contact-Poisonous Plants of the World". mic-ro.com.

- ↑ Chaker, Anne Marie; Athavaley, Anjali (June 22, 2010). "Least-Welcome Sign of Summer". The Wall Street Journal. p. D1.

- ↑ Robert L. Rietschel; Joseph F. Fowler; Alexander A. Fisher (2008). Fisher's contact dermatitis. PMPH-USA. pp. 408–. ISBN 978-1-55009-378-0. Retrieved 26 July 2010.

- ↑ Wilson, W. H. & Lowdermilk, P. (2006). Maternal Child Nursing Care (3rd edition). St. Louis: Mosby Elsevier.

- ↑ "American Topics. An Outdated Notion, That Calamine Lotion". Archived from the original on 2007-06-19. Retrieved 2007-07-19.

- ↑ Appel, L.M. Ohmart; Sterner, R.F. (1956). "Zinc oxide: A new, pink, refractive microform crystal". AMA Arch Dermatol. 73 (4): 316–324. PMID 13301048.

- ↑ "American Academy of Dermatology – Poison Ivy, Oak & Sumac".

- ↑ Long, D.; Ballentine, N. H.; Marks, J. G. (1997). "Treatment of poison ivy/oak allergic contact dermatitis with an extract of jewelweed.". Am. J. Contact. Dermat. 8 (3): 150–3. PMID 9249283. doi:10.1097/01206501-199709000-00005.

- ↑ Gibson, MR; Maher, FT (1950). "Activity of jewelweed and its enzymes in the treatment of Rhus dermatitis.". Journal of the American Pharmaceutical Association. American Pharmaceutical Association. 39 (5): 294–6. PMID 15421925. doi:10.1002/jps.3030390516.

- ↑ Guin, J. D.; Reynolds, R. (1980). "Jewelweed treatment of poison ivy dermatitis.". Contact Dermatitis. 6 (4): 287–8. PMID 6447037. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1980.tb04935.x.

- ↑ Zink, B. J.; Otten, E. J.; Rosenthal, M.; Singal, B. (1991). "The effect of jewel weed in preventing poison ivy dermatitis.". Journal of Wilderness Medicine. 2 (3): 178–182. doi:10.1580/0953-9859-2.3.178.

- ↑ Extreme Deer Habitat (2014-06-22), How to never have a serious poison ivy rash again, retrieved 2016-07-26

- ↑ "Facts about Poison Ivy: Is it contagious?".

- ↑ Editors of Prevention (2 March 2010). The Doctors Book of Home Remedies: Quick Fixes, Clever Techniques, and Uncommon Cures to Get You Feeling Better Fast. Rodale. pp. 488–. ISBN 978-1-60529-866-5.

- ↑ "Facts about Poison Ivy: How do you get poison ivy?".

- ↑ Robert Alan Lewis (1998). Lewis' dictionary of toxicology. CRC Press. pp. 901–. ISBN 978-1-56670-223-2. Retrieved 18 August 2010.

- ↑ "Facts about Poison Ivy: How long does the rash last?, What can you do once the itching starts?, How do you get poison ivy?".

- ↑ "404 Error: Page not found". aad.org.

- ↑ "Facts about Poison Ivy: How do you get poison ivy?, Pets and Poison Ivy, How long does the oil last?".

- ↑ Mangos and Poison Ivy (New England Journal of Medicine Web Article)

- ↑ Rosen, T.; Fordice, D. B. (April 1994). "Cashew Nut Dermatitis". Southern Medical Journal. 87 (4): 543–546. PMID 8153790. doi:10.1097/00007611-199404000-00026. Retrieved 2011-01-13.

- ↑ "Misconceptions About Treating Poison Ivy and Oak Rash". teclabsinc.com.

- ↑ Gladman, Aaron C. (June 2006). "Toxicodendron Dermatitis: Poison Ivy, Oak, and Sumac". Wilderness & Environmental Medicine. 17 (2): 120–128. PMID 16805148. doi:10.1580/PR31-05.1. Retrieved 18 July 2016.

- ↑ Sims, Lorelei (2006). The Backyard Blacksmith Traditional Techniques for the Modern Smith. United States of America: Quarry Books. p. 38. ISBN 1-59253-251-9.

- ↑ "Botanical Dermatology – ALLERGIC CONTACT DERMATITIS – ANACARDIACEAE AND RELATED FAMILIES". The Internet Dermatology Society, Inc. Retrieved 22 Sep 2014.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Rhus radicans. |

- Contact-Poisonous Plants of the World

- Toxicodendron radicans images at bioimages. vanderbilt.edu

- Poison Oak at Wayne's Word

- Poison Ivy Plant and Rash Images, advice, plant identification

- Poison Ivy, Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs

- Common weeds of the northern United States and Canada: Western poison oak, poison ivy and poison sumac. (Anacardiaceae-family)

- Poison ivy effects and identification

- How to recognize Eastern Poison Ivy, and more

- Poison ivy rash treatment