Tourmaline

| Tourmaline | |

|---|---|

| |

| General | |

| Category | Cyclosilicate |

| Formula (repeating unit) |

(Ca,K,Na,[])(Al,Fe,Li,Mg,Mn)3(Al,Cr, Fe,V)6 (BO3)3(Si,Al,B)6O18(OH,F)4 [1][2] |

| Crystal system | Trigonal |

| Crystal class |

Ditrigonal pyramidal (3m) H-M symbol: (3m) |

| Identification | |

| Color | Most commonly black, but can range from colorless to brown, red, orange, yellow, green, blue, violet, pink, or hues in between; can be bi-colored, or even tri-colored; rarely can be neon green or electric blue |

| Crystal habit | Parallel and elongated. Acicular prisms, sometimes radiating. Massive. Scattered grains (in granite). |

| Cleavage | Indistinct |

| Fracture | Uneven, small conchoidal, brittle |

| Tenacity | brittle |

| Mohs scale hardness | 7–7.5 |

| Luster | Vitreous, sometimes resinous |

| Streak | White |

| Diaphaneity | translucent to opaque |

| Specific gravity | 3.06 (+.20 -.06)[1] |

| Density | 2.82–3.32 |

| Polish luster | Vitreous[1] |

| Optical properties | Double refractive, uniaxial negative[1] |

| Refractive index | nω=1.635–1.675, nε=1.610–1.650 |

| Birefringence | -0.018 to −0.040; typically about .020 but in dark stones it may reach .040[1] |

| Pleochroism |

typically moderate to strong[1] Red Tourmaline: Definite; dark red, light red Green Tourmaline: Strong; dark green, yellow-green Brown Tourmaline: Definite; dark brown, light brown Blue Tourmaline: Strong; dark blue, light blue |

| Dispersion | .017[1] |

| Ultraviolet fluorescence | pink stones—inert to very weak red to violet in long and short wave[1] |

| Absorption spectra | a strong narrow band at 498 nm, and almost complete absorption of red down to 640nm in blue and green stones; red and pink stones show lines at 458 and 451nm as well as a broad band in the green spectrum[1] |

Tourmaline ( /ˈtʊərməliːn/ TOOR-mə-leen) is a crystalline boron silicate mineral compounded with elements such as aluminium, iron, magnesium, sodium, lithium, or potassium. Tourmaline is classified as a semi-precious stone and the gemstone comes in a wide variety of colors. The name comes from the Tamil and Sinhalese word "Turmali" (තුරමලි) or "Thoramalli" (තෝරමල්ලි), which applied to different gemstones found in Sri Lanka.

History

Brightly colored Sri Lankan gem tourmalines were brought to Europe in great quantities by the Dutch East India Company to satisfy a demand for curiosities and gems. At the time it was not realised that schorl and tourmaline were the same mineral (it was only about 1703 that it was discovered that some colored gems weren't zircons). Tourmaline was sometimes called the "Ceylonese [Sri Lankan] Magnet" because it could attract and then repel hot ashes due to its pyroelectric properties.[2][3]

Tourmalines were used by chemists in the 19th century to polarize light by shining rays onto a cut and polished surface of the gem.[4]

Species and varieties

Commonly encountered species and varieties:

Schorl species:

- Brownish black to black—schorl

Dravite species: from the Drave district of Carinthia

- Dark yellow to brownish black—dravite

Elbaite species: named after the island of Elba, Italy

- Red or pinkish-red—rubellite variety

- Light blue to bluish green—Brazilian indicolite variety (from indigo)

- Green—verdelite or Brazilian emerald variety

- Colorless—achroite variety (from the Greek "άχρωμος" meaning "colorless")

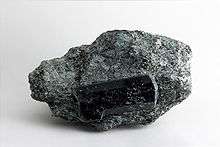

Schorl

The most common species of tourmaline is schorl, the sodium iron (divalent) endmember of the group. It may account for 95% or more of all tourmaline in nature. The early history of the mineral schorl shows that the name "schorl" was in use prior to 1400 because a village known today as Zschorlau (in Saxony, Germany) was then named "Schorl" (or minor variants of this name). This village had a nearby tin mine where, in addition to cassiterite, black tourmaline was found. The first description of schorl with the name "schürl" and its occurrence (various tin mines in the Saxony Ore Mountains) was written by Johannes Mathesius (1504–1565) in 1562 under the title "Sarepta oder Bergpostill".[5] Up to about 1600, additional names used in the German language were "Schurel", "Schörle", and "Schurl". Beginning in the 18th century, the name Schörl was mainly used in the German-speaking area. In English, the names shorl and shirl were used in the 18th century. In the 19th century the names common schorl, schörl, schorl and iron tourmaline were the English words used for this mineral.[5]

Dravite

Dravite, also called brown tourmaline, is the sodium magnesium rich tourmaline endmember. Uvite, in comparison, is a calcium magnesium tourmaline. Dravite forms multiple series, with other tourmaline members, including schorl and elbaite.

The name dravite was used for the first time by Gustav Tschermak (1836–1927), Professor of Mineralogy and Petrography at the University of Vienna, in his book Lehrbuch der Mineralogie (published in 1884) for magnesium-rich (and sodium-rich) tourmaline from Unterdrauburg in the Drava river area, Carinthia, Austro-Hungarian Empire. Today this tourmaline locality (type locality for dravite) at Dravograd (near Dobrova pri Dravogradu), is a part of the Republic of Slovenia.[6] Tschermak gave this tourmaline the name dravite, for the Drava river area, which is the district along the Drava River (in German: Drau, in Latin: Drave) in Austria and Slovenia. The chemical composition which was given by Tschermak in 1884 for this dravite approximately corresponds to the formula NaMg3(Al,Mg)6B3Si6O27(OH), which is in good agreement (except for the OH content) with the endmember formula of dravite as known today.[6]

Dravite varieties include the deep green chromium dravite and the vanadium dravite.

Elbaite

A lithium-tourmaline elbaite was one of three pegmatitic minerals from Utö, Sweden, in which the new alkali element lithium (Li) was determined in 1818 by Johan August Arfwedson for the first time.[7] Elba Island, Italy, was one of the first localities where colored and colorless Li-tourmalines were extensively chemically analysed. In 1850 Karl Friedrich August Rammelsberg described fluorine (F) in tourmaline for the first time. In 1870 he proved that all varieties of tourmaline contain chemically bound water. In 1889 Scharitzer proposed the substitution of (OH) by F in red Li-tourmaline from Sušice, Czech Republic. In 1914 Vladimir Vernadsky proposed the name Elbait for lithium-, sodium-, and aluminum-rich tourmaline from Elba Island, Italy, with the simplified formula (Li,Na)HAl6B2Si4O21.[7] Most likely the type material for elbaite was found at Fonte del Prete, San Piero in Campo, Campo nell'Elba, Elba Island, Province of Livorno, Tuscany, Italy.[7] In 1933 Winchell published an updated formula for elbaite, H8Na2Li3Al3B6Al12Si12O62, which is commonly used to date written as Na(Li1.5Al1.5)Al6(BO3)3[Si6O18](OH)3(OH).[7] The first crystal structure determination of a Li-rich tourmaline was published in 1972 by Donnay and Barton, performed on a pink elbaite from San Diego County, California, United States.

Chemical composition of the tourmaline group

The tourmaline mineral group is chemically one of the most complicated groups of silicate minerals. Its composition varies widely because of isomorphous replacement (solid solution), and its general formula can be written as

XY3Z6(T6O18)(BO3)3V3W,

where:[8]

X = Ca, Na, K, □ = vacancy

Y = Li, Mg, Fe2+, Mn2+, Zn, Al, Cr3+, V3+, Fe3+, Ti4+, vacancy

Z = Mg, Al, Fe3+, Cr3+, V3+

B = B, vacancy

W = OH, F, O

| Adachiite | CaFe2+3Al6(Si5AlO18)(BO3)3(OH)3OH |

| Bosiite | NaFe3+3(Al4Mg2)Si6O18(BO3)3(OH)3O |

| Chromium-dravite | NaMg3Cr6Si6O18(BO3)3(OH)3OH |

| Chromo-alumino-povondraite | NaCr3(Al4Mg2)Si6O18(BO3)3(OH)3O |

| Darrellhenryite | NaLiAl2Al6Si6O18(BO3)3(OH)3O |

| Dravite | NaMg3Al6Si6O18(BO3)3(OH)3OH |

| Elbaite | Na(Li1.5,Al1.5)Al6Si6O18(BO3)3(OH)3OH |

| Feruvite | CaFe2+3(MgAl5)Si6O18(BO3)3(OH)3OH |

| Fluor-buergerite | NaFe3+3Al6Si6O18(BO3)3O3F |

| Fluor-dravite | NaMg3Al6Si6O18(BO3)3(OH)3F |

| Fluor-elbaite | Na(Li1.5,Al1.5)Al6Si6O18(BO3)3(OH)3F |

| Fluor-liddicoatite | Ca(Li2Al)Al6Si6O18(BO3)3(OH)3F |

| Fluor-schorl | NaFe2+3Al6Si6O18(BO3)3(OH)3F |

| Fluor-tsilaisite | NaMn2+3Al6Si6O18(BO3)3(OH)3F |

| Fluor-uvite | CaMg3(Al5Mg)Si6O18(BO3)3(OH)3F |

| Foitite | □(Fe2+2Al)Al6Si6O18(BO3)3(OH)3OH |

| Lucchesiite | Ca(Fe2+)3Al6Si6O18(BO3)3(OH)3O |

| Luinaite-(OH) | (Na,□)(Fe2+,Mg)3Al6Si6O18(BO3)3(OH)3OH |

| Magnesio-foitite | □(Mg2Al)Al6Si6O18(BO3)3(OH)3OH |

| Maruyamaite | K(MgAl2)(Al5Mg)Si6O18(BO3)3(OH)3O |

| Olenite | NaAl3Al6Si6O18(BO3)3O3OH |

| Oxy-chromium-dravite | NaCr3(Mg2Cr4)Si6O18(BO3)3(OH)3O |

| Oxy-dravite | Na(Al2Mg)(Al5Mg)Si6O18(BO3)3(OH)3O |

| Oxy-foitite | □(Fe2+Al2)Al6Si6O18(BO3)3(OH)3O |

| Oxy-schorl | Na(Fe2+2Al)Al6Si6O18(BO3)3(OH)3O |

| Oxy-vanadium-dravite | NaV3(V4Mg2)Si6O18(BO3)3(OH)3O |

| Povondraite | NaFe3+3(Fe3+4Mg2)Si6O18(BO3)3(OH)3O |

| Rossmanite | □(LiAl2)Al6Si6O18(BO3)3(OH)3OH |

| Schorl | NaFe2+3Al6Si6O18(BO3)3(OH)3OH |

| Tsilaisite | NaMn2+3Al6Si6O18(BO3)3(OH)3OH |

| Uvite | CaMg3(Al5Mg)Si6O18(BO3)3(OH)3OH |

| Vanadio-oxy-chromium-dravite | NaV3(Cr4Mg2)Si6O18(BO3)3(OH)3O |

| Vanadio-oxy-dravite | NaV3(Al4Mg2)Si6O18(BO3)3(OH)3O |

A revised nomenclature for the tourmaline group was published in 2011.[9][10][11]

Physical properties

Crystal structure

Tourmaline is a six-member ring cyclosilicate having a trigonal crystal system. It occurs as long, slender to thick prismatic and columnar crystals that are usually triangular in cross-section, often with curved striated faces. The style of termination at the ends of crystals is sometimes asymmetrical, called hemimorphism. Small slender prismatic crystals are common in a fine-grained granite called aplite, often forming radial daisy-like patterns. Tourmaline is distinguished by its three-sided prisms; no other common mineral has three sides. Prisms faces often have heavy vertical striations that produce a rounded triangular effect. Tourmaline is rarely perfectly euhedral. An exception was the fine dravite tourmalines of Yinnietharra, in western Australia. The deposit was discovered in the 1970s, but is now exhausted. All hemimorphic crystals are piezoelectric, and are often pyroelectric as well.

Color

Tourmaline has a variety of colors. Usually, iron-rich tourmalines are black to bluish-black to deep brown, while magnesium-rich varieties are brown to yellow, and lithium-rich tourmalines are almost any color: blue, green, red, yellow, pink, etc. Rarely, it is colorless. Bi-colored and multicolored crystals are common, reflecting variations of fluid chemistry during crystallization. Crystals may be green at one end and pink at the other, or green on the outside and pink inside; this type is called watermelon tourmaline. Some forms of tourmaline are dichroic, in that they change color when viewed from different directions.

The pink color of tourmalines from many localities is the result of prolonged natural irradiation. During their growth, these tourmaline crystals incorporated Mn2+ and were initially very pale. Due to natural gamma ray exposure from radioactive decay of 40K in their granitic environment, gradual formation of Mn3+ ions occurs, which is responsible for the deepening of the pink to red color.[12]

Magnetism

Opaque black schorl and yellow tsilaisite are idiochromatic tourmaline species that have high magnetic susceptibilities due to high concentrations of iron and manganese respectively. Most gem-quality tourmalines are of the elbaite species. Elbaite tourmalines are allochromatic, deriving most of their color and magnetic susceptibility from schorl (which imparts iron) and tsilaisite (which imparts manganese).

Red and pink tourmalines have the lowest magnetic susceptibilities among the elbaites, while tourmalines with bright yellow, green and blue colors are the most magnetic elbaites. Dravite species such as green chromium dravite and brown dravite are diamagnetic. A handheld neodymium magnet can be used to identify or separate some types of tourmaline gems from others. For example, blue indicolite tourmaline is the only blue gemstone of any kind that will show a drag response when a neodymium magnet is applied. Any blue tourmaline that is diamagnetic can be identified as paraiba tourmaline colored by copper in contrast to magnetic blue tourmaline colored by iron.[13]

Treatments

Some tourmaline gems, especially pink to red colored stones, are altered by heat treatment to improve their color. Overly dark red stones can be lightened by careful heat treatment. The pink color in manganese-containing near-colorless to pale pink stones can be greatly increased by irradiation with gamma-rays or electron beams. Irradiation is almost impossible to detect in tourmalines, and does not, currently, impact the value. Heavily-included tourmalines, such as rubellite and Brazilian paraiba, are sometimes clarity-enhanced. A clarity-enhanced tourmaline (especially the paraiba variety) is worth much less than a non-treated gem.[14]

Geology

Tourmaline is found in granite and granite pegmatites and in metamorphic rocks such as schist and marble. Schorl and lithium-rich tourmalines are usually found in granite and granite pegmatite. Magnesium-rich tourmalines, dravites, are generally restricted to schists and marble. Tourmaline is a durable mineral and can be found in minor amounts as grains in sandstone and conglomerate, and is part of the ZTR index for highly weathered sediments.

Localities

Gem and specimen tourmaline is mined chiefly in Brazil and Africa. Some placer material suitable for gem use comes from Sri Lanka. In addition to Brazil, tourmaline is mined in Tanzania, Nigeria, Kenya, Madagascar, Mozambique, Namibia, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, and Malawi.[15]

United States

Some fine gems and specimen material has been produced in the United States, with the first discoveries in 1822, in the state of Maine. California became a large producer of tourmaline in the early 1900s. The Maine deposits tend to produce crystals in raspberry pink-red as well as minty greens. The California deposits are known for bright pinks, as well as bicolors. During the early 1900s, Maine and California were the world's largest producers of gem tourmalines. The Empress Dowager Cixi of China loved pink tourmaline and bought large quantities for gemstones and carvings from the then new Himalaya Mine, located in San Diego County, California.[16] It is not clear when the first tourmaline was found in California. Native Americans have used pink and green tourmaline as funeral gifts for centuries. The first documented case was in 1890 when Charles Russel Orcutt found pink tourmaline at what later became the Stewart Mine at Pala, San Diego County.[17]

Brazil

Almost every color of tourmaline can be found in Brazil, especially in the Brazilian states of Minas Gerais and Bahia. In 1989, miners discovered a unique and brightly colored variety of tourmaline in the state of Paraíba. The new type of tourmaline, which soon became known as paraiba tourmaline, came in blue and green. Brazilian paraiba tourmaline usually contains abundant inclusions. Much of the paraiba tourmaline from Brazil actually comes from the neighboring state of Rio Grande do Norte. Material from Rio Grande do Norte is often somewhat less intense in color, but many fine gems are found there. It was determined that the element copper was important in the coloration of the stone.[18]

World's largest

A large cut tourmaline from Paraiba, measuring 36.44 x 33.75 x 21.85 mm (1.43 x 1.33 x 0.86 in) and weighing 191.87 carats, was included in the Guinness World Records.[19] The large natural gem, owned by Billionaire Business Enterprises,[19] is a bluish-green in color. The flawless oval shaped cut stone was presented in Montreal, Quebec, Canada on 14 October 2009.[20]

Africa

In the late 1990s, copper-containing tourmaline was found in Nigeria. The material was generally paler and less saturated than the Brazilian materials, although the material generally was much less included. A more recent African discovery from Mozambique has also produced tourmaline colored by copper, similar to the Brazilian paraiba. While its colors are somewhat less bright than top Brazilian material, Mozambique paraiba is often less included and has been found in larger sizes. The Mozambique paraiba material usually is more intensely colored than the Nigerian. There is a significant overlap in color and clarity with Mozambique paraiba and Brazilian paraiba, especially with the material from Rio Grande do Norte. While less expensive than top quality Brazilian paraiba, some Mozambique material sells for well over $5,000 per carat, which still is extremely high compared to other tourmalines.

Another highly valuable variety is chrome tourmaline, a rare type of dravite tourmaline from Tanzania. Chrome tourmaline is a rich green color due to the presence of chromium atoms in the crystal; chromium also produces the green color of emeralds. Of the standard elbaite colors, blue indicolite gems are typically the most valuable,[21] followed by green verdelite and pink to red rubellite. There are also yellow tourmalines, sometimes known as canary tourmaline. Zambia is rich in both red and yellow tourmaline, which are relatively inexpensive in that country. Ironically the rarest variety, colorless achroite, is not appreciated and is the least expensive of the transparent tourmalines.

Afghanistan

Indicolite (blue tourmaline) and verdelite (green tourmaline) are found in the Nuristan region (Ghazi Abad district) and Pech Valley (Pech and Chapa Dara districts) of Kunar province. Gem-quality tourmalines are faceted (cut) from 0.50–10 gram sizes and have high clarity and intense shades of color.

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Gemological Institute of America, GIA Gem Reference Guide 1995, ISBN 0-87311-019-6

- 1 2 Mindat tourmaline group Accessed September 12, 2005. This website details specifically and clearly how the complicated chemical formula is structured.

- ↑ Jiri Erhart, Erwin Kittinger, Jana Prívratská (2010). Fundamentals of Piezoelectric Sensorics: Mechanical, Dielectric, and Thermodynamical Properties of Piezoelectric Materials. Springer. p. 4.

- ↑ Draper, John William (1861). A Textbook on chemistry. New York: Harper and Brothers. p. 93.

- 1 2 Ertl, 2006.

- 1 2 Ertl, 2007.

- 1 2 3 4 Ertl, 2008.

- ↑ Hawthorne, F.C. & Henry, D.J. (1999). "Classification of the minerals of the tourmaline group". European Journal of Mineralogy, 11, pp. 201–215.

- ↑ Darrell J. Henry, Milan Novák, Frank C. Hawthorne, Andreas Ertl, Barbara L. Dutrow, Pavel Uher, and Federico Pezzotta (2011). "Nomenclature of the tourmaline-supergroup minerals" (PDF). American Mineralogist. 96: 895–913. doi:10.2138/am.2011.3636.

- ↑ Erratum: American Mineralogist (2013), Volume 98, page 524.

- ↑ Frank C. Hawthorne and Dona M. Dirlam. "Tourmaline: Tourmaline the Indicator Mineral: From Atomic Arrangement to Viking Navigation." Elements, October 2011, v. 7, p. (5): 307–312, doi:10.2113/gselements.7.5.307.

- ↑ Reinitz & Rossman, 1998.

- ↑ Kirk Feral Magnetism in Gemstones

- ↑ Kurt Nassau (1984), Gemstone Enhancement: Heat, Irradiation, Impregnation, Dyeing, and Other Treatments, Butterworth Publishers

- ↑ Hurlbut and Klien. Manual of Mineralogy (after Dana), 19th Edition, John Wiley and Sons, Publishers

- ↑ Fred Rynerson, Exploring and Mining Gems and Gold in the West, Naturegraph Publishers.

- ↑ Paul Willard Johnson, "Common Gems of San Diego," Gems and Gemology, Vol. XII, Winter 1968–69, p. 358.

- ↑ Rossman et al. 1991.

- 1 2 Guinness World Records Official Website

- ↑ Giant jewel breaks record

- ↑ Allison Augustyn, Lance Grande (2009). Gems and Gemstones: Timeless Natural Beauty of the Mineral World. University of Chicago Press. p. 152. ISBN 0226305112.

References

- Ertl, A., Pertlik, F. & Bernhardt, H.-J. (1997) Investigations on olenite with excess boron from the Koralpe, Styria, Austria, Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften, Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftliche Klasse, Abt. I, Anzeiger, 134, pp. 3–10. Article Online

- Ertl, A. (2006) About the etymology and the type localities of schorl Mitteilungen der Österreichischen Mineralogischen Gesellschaft, 152, 2006, pp. 7–16. Article Online

- Ertl, A. (2007) About the type locality and the nomenclature of dravite Mitteilungen der Österreichischen Mineralogischen Gesellschaft, 153, 2007, pp. 265–271. Article Online

- Ertl, A. (2008) About the nomenclature and the type locality of elbaite: A historical review Mitteilungen der Österreichischen Mineralogischen Gesellschaft, 154, 2008, pp. 35–44. Article Online

- Reinitz, I.M. & Rossman G.R. (1988). "Role of natural radiation in tourmaline coloration". American Mineralogist, 73, pp. 822–825. Article Online

- Rossman, G.R., Fritsch E., & Shigley J.E. (1991). "Origin of color in cuprian elbaite from São José de Batalha, Paraíba, Brazil". American Mineralogist, 76, pp. 1479–1484. Article Online

- Schumann, Walter (2006). Gemstones of the World, 3rd Edition. Sterling Publishing, New York; pp. 126–127.

Further reading

- Darrell J. Henry; Milan Novák; Frank C. Hawthorne; Andreas Ertl; Barbara L. Dutrow; Pavel Uher & Federico Pezzotta (2011). "Nomenclature of the tourmaline-supergroup minerals". American Mineralogist. 96: 895–913. doi:10.2138/am.2011.3636.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tourmaline. |

| Look up tourmaline in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Tourmaline classification Accessed October 8, 2011

- Mindat tourmaline group Accessed October 8, 2011

- ICA's tourmaline page International Colored Stone Association on tourmaline

- Farlang historical tourmaline references US localities, antique references,

- Webmineral elbaite page, crystallographic and mineral information on elbaite

- Tourmaline Characteristics and Geological data