Tool use by animals

Tools are used by animals to perform behaviours including the acquisition of food and water, grooming, defense, recreation or construction. Originally thought to be a skill only possessed by humans, some tool use requires a sophisticated level of cognition. There is considerable discussion about the definition of what constitutes a tool and therefore which behaviours can be considered as true examples of tool use. A wide range of animals are considered to use tools including mammals, birds, fish, cephalopods and insects.

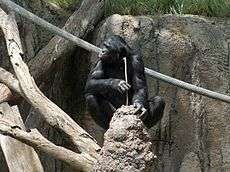

Primates are well known for using tools for hunting or gathering food and water, cover for rain, and self-defence. Chimpanzees have been the object of study, most famously by Jane Goodall, since these animals are more-often kept in captivity than other primates and are closely related to humans. Tool-use in other primates are lesser-known as many of them are mainly observed in the wild. Many famous researchers, such as Charles Darwin in his book The Descent of Man, mentioned tool-use in monkeys (such as baboons). Both wild and captive elephants are known to create tools using their trunk and feet, mainly for swatting flies, scratching, plugging water-holes (so the water doesn't evaporate), and reaching food that is out of reach. A group of dolphins in Shark Bay use sponges to protect their beak while foraging. Sea otters will dislodge food from rocks (such as abalone) and break open shellfish. Carnivores (of the order Carnivora) can use tools to trap prey or break open the shells of prey, as well as for scratching.

Corvids (crows, ravens and rooks) are well known for their large brains (among birds) and subsequent tool use. They mainly manufacture probes out of twigs and wood (and sometimes metal wire) to catch or impale larvae. Crows are among the only animals that create their own toys. Tool use in other birds is best exemplified in nest intricacy. Warblers manufacture 'pouches' to make their nests in. Some birds, such as weaver birds build complex nests. Finches and woodpeckers may insert twigs into trees in order to catch or impale larvae. Parrots may use tools to wedge nuts so that they may crack it open (using a tool) without launching it away. Some birds take advantage of human activity, such as seagulls which drop shellfish in front of cars to crack them open.

Several species of fish use tools to crack open shellfish, extract food that is out of reach, cleaning an area (for nesting), and hunting. Octopuses gather coconut shells and create a shelter. They may also construct a fence using rocks.

Definitions and terminology

The key to identifying tool use is defining what constitutes a tool. Researchers of animal behavior have arrived at different formulations.

In 1980, Beck published a widely used definition of tool use.[1] This has been modified to:

"The external employment of an unattached or manipulable attached environmental object to alter more efficiently the form, position, or condition of another object, another organism, or the user itself, when the user holds and directly manipulates the tool during or prior to use and is responsible for the proper and effective orientation of the tool.[2]

Other, briefer definitions have been proposed:

"An object carried or maintained for future use"— Finn, Tregenza, and Norman, 2009.[3]

"The use of physical objects other than the animal's own body or appendages as a means to extend the physical influence realized by the animal"— Jones and Kamil, 1973[4]

"An object that has been modified to fit a purpose" or "An inanimate object that one uses or modifies in some way to cause a change in the environment, thereby facilitating one's achievement of a target goal".— Hauser, 2000[5]

Others, for example Lawick-Goodall,[6] distinguish between "tool use" and "object use".

Different terms have been given to the tool according to whether the tool is altered by the animal. If the "tool" is not held or manipulated by the animal in any way, such as an immobile anvil, objects in a bowerbird's bower, or a bird using bread as bait to catch fish,[7] it is sometimes referred to as a "proto-tool". Several studies in primates and birds have found that tool use is correlated with an enlargement of the brain as a whole or of particular regions. For example, true tool-using birds have relatively larger brains than proto-tool users.[8]

When an animal uses a tool that acts on another tool, this has been termed use of a "meta-tool". For example, New Caledonian crows will spontaneously use a short tool to obtain an otherwise inaccessible longer tool that then allows them to extract food from a hole.[8] Similarly, bearded capuchin monkeys will use smaller stones to loosen bigger quartz pebbles embedded in conglomerate rock, which they subsequently use as tools.[9]

Rarely, animals may use one tool followed by another, for example, bearded capuchins use stones and sticks, or two stones.[9] This is called "associative", "secondary" or "sequential" tool use.[10]

Some animals use other individuals in a way which could be interpreted as tool use, for example, ants crossing water over a bridge of other ants, or weaver ants using conspecifics to glue leaves together. These have been termed "social tools".[11]

Borderline examples

Play: Play has been defined as “activity having no immediate benefits and structurally including repetitive or exaggerated actions that may be out of sequence or disordered”.[12] When play is discussed in relation to manipulating objects, it is often used in association with the word "tool".[13] Some birds, notably crows, parrots and birds of prey "play" with objects, many of them playing in flight with such items as stones, sticks, leaves, by letting them go and catching them again before they reach the ground. A few species repeatedly drop stones, apparently for the enjoyment of the sound effects.[14] Many other species of animals, both avian and non-avian, play with objects in a similar manner.[2]

Fixed "devices:" The impaling of prey on thorns by many of the shrikes (Laniidae) is well known.[15] Several other birds may use spines or forked sticks to anchor a carcass while they flay it with the bill. It has been concluded that "This is an example of a fixed device which serves as an extension of the body, in this case, talons" and is thus a true form of tool use. On the other hand, the use of fixed skewers may not be true tool-use because the thorn (or whatever) is not manipulated by the bird.[14] Leopards perform a similar behaviour by dragging carcasses up trees and caching them in the forks of branches.[16]

Use of baits: Several species of bird, including herons such as the striated heron (Butorides striatus) will place bread in the water to attract fish.[14][17][18] Whether this is tool use is disputed because the bread is not manipulated or held by the bird.[19]

Learning and cognition

Tool use by animals may indicate different levels of learning and cognition. For some animals, tool use is largely instinctive and inflexible. For example, the woodpecker finch of the Galápagos Islands use twigs or spines as an essential and regular part of its foraging behaviour, however, these behaviours are often quite inflexible and are not applied effectively in different situations. Other tool use, e.g. chimpanzees using twigs to "fish" for termites, may be developed by watching others use tools and may even be a true example of animal teaching. Tools may even be used in solving puzzles in which the animal appears to experience a "Eureka moment".

In mammals

Primates

Tool use has been reported many times in both wild and captive primates, particularly the great apes. The use of tools by primates is varied and includes hunting (mammals, invertebrates, fish), collecting honey, processing food (nuts, fruits, vegetables and seeds), collecting water, weapons and shelter.

In 1960, Jane Goodall observed a chimpanzee poking pieces of grass into a termite mound and then raising the grass to his mouth. After he left, Goodall approached the mound and repeated the behaviour because she was unsure what the chimpanzee was doing. She found that the termites bit onto the grass with their jaws. The chimpanzee had been using the grass as a tool to "fish" or "dip" for termites.[20]

Tool manufacture is much rarer than simple tool use and probably represents higher cognitive functioning. Soon after her initial discovery of tool use, Goodall observed other chimpanzees picking up leafy twigs, stripping off the leaves and using the stems to fish for insects. This change of a leafy twig into a tool was a major discovery. Prior to this, scientists thought that only humans manufactured and used tools, and that this ability was what separated humans from other animals.[20] In 1990, it was claimed the only primate to manufacture tools in the wild was the chimpanzee.[21] However, since then, several primates have been reported as tool makers in the wild.[22]

Both bonobos and chimpanzees have been observed making "sponges" out of leaves and moss that suck up water and using these for grooming. Sumatran orangutans will take a live branch, remove twigs and leaves and sometimes the bark, before fraying or flattening the tip for use on ant or bees.[23] In the wild, mandrills have been observed to clean their ears with modified tools. Scientists filmed a large male mandrill at Chester Zoo (UK) stripping down a twig, apparently to make it narrower, and then using the modified stick to scrape dirt from underneath his toenails.[24] Captive gorillas have made a variety of tools.[25]

Chimpanzees and bonobos

Common chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) are sophisticated tool users with behaviors including cracking nuts with stone tools and fishing for ants or termites with sticks. There are more limited reports of the closely related bonobo (Pan paniscus) using tools in the wild; it has been claimed they rarely use tools in the wild although they use tools as readily as chimpanzees when in captivity,[26] It has been reported that females of both chimpanzees and bonobos use tools more avidly than males.[27] Wild chimpanzees predominantly use tools in the context of food acquisition, while wild bonobos appear to use tools mainly for personal care (cleaning, protection from rain) and social purposes. Wild bonobos have been observed using leaves as cover for rain, or the use of branches in social displays.[26]

- Hunting

Research in 2007 showed that common chimpanzees sharpen sticks to use as weapons when hunting mammals. This is considered the first evidence of systematic use of weapons in a species other than humans. Researchers documented 22 occasions when wild chimpanzees on a savanna in Senegal fashioned sticks into "spears" to hunt lesser bushbabies (Galago senegalensis).[28] In each case, a chimpanzee modified a branch by breaking off one or two ends and, frequently using its teeth, sharpened the stick. The tools, on average, were about 60 cm (24 in) long and 1.1 cm (0.4 in) in circumference. The chimpanzee then jabbed the spear into hollows in tree trunks where bushbabies sleep.[29] There was a single case in which a chimpanzee successfully extracted a bushbaby with the tool. It has been suggested that the word "spear" is an overstatement that makes the chimpanzees seem too much like early humans, and that the term "bludgeon" is more accurate, since the point of the tool may not be particularly sharp.[30] This behaviour was seen more frequently in females, particularly adolescent females, and young chimps in general, than in adult males.[31]

Chimpanzees often eat the marrow of long bones of colobus monkeys with the help of small sticks, after opening the ends of the bones with their teeth.[32] A juvenile female was observed to eat small parts of the brain of an intact skull that she could not break open by inserting a small stick through the foramen magnum. On another occasion, an adult female used three sticks to clean the orbits of a colobus monkey skull after she had just eaten the eyes.[21]

In Gombe National Park in 1960, Jane Goodall observed a chimpanzee, David Greybeard, poking pieces of grass into a termite mound and then raising the grass to his mouth. After he left, Goodall approached the mound and repeated the behaviour because she was unsure what David was doing. She found that the termites bit onto the grass with their jaws. David had been using the grass as a tool to "fish" or "dip" for termites.[20] Soon after this initial discovery of tool use, Goodall observed David and other chimpanzees picking up leafy twigs, stripping off the leaves, and using the stems to fish for insects. This modification of a leafy twig into a tool was a major discovery: previously, scientists thought that only humans made and used tools, and that this was what separated humans from other animals.[20]

Other studies of the Gombe chimps show that young females and males learn to fish for termites differently. Female chimps learn to fish for termites earlier and better than the young males.[33] Females also spend more time fishing while at the mounds with their mothers—males spend more time playing. When they are adults, females need more termite protein because with young to care for, they cannot hunt the way males can.[34]

Populations differ in the prevalence of tool use for fishing for invertebrates. Chimpanzees in the Tai National Park only sometimes use tools, whereas Gombe chimpanzees rely almost exclusively on tools for their intake of driver ants. This may be due to difference in the rewards gained by tool use: Gombe chimpanzees collect 760 ants/min compared to 180 ants/min for the Tai chimpanzees.[21]

Some chimpanzees use tools to hunt large bees (Xylocopa sp.) which make nests in dead branches on the ground or in trees. To get to the grubs and the honey, the chimpanzee first tests for the presence of adults by probing the nest entrance with a stick. If present, adult bees block the entrance with their abdomens, ready to sting. The chimpanzee then disables them with the stick to make them fall out and eats them rapidly. Afterwards, the chimpanzee opens the branch with its teeth to obtain the grubs and the honey.[21]

Chimpanzees have even been observed using two tools: a stick to dig into an ant nest and a "brush" made from grass stems with their teeth to collect the ants.[21]

- Collecting honey

Honey of four bee species is eaten by chimpanzees. Groups of chimpanzees fish with sticks for the honey after having tried to remove what they can with their hands. They usually extract with their hands honeycombs from undisturbed hives of honey bees and run away from the bees to quietly eat their catch. In contrast, hives that have already been disturbed, either through the falling of the tree or because of the intervention of other predators, are cleaned of the remaining honey with fishing tools.[21]

- Processing food

Tai chimpanzees crack open nuts with rocks, but there is no record of Gombe chimpanzees using rocks in this way.[20] After opening nuts by pounding with a hammer, parts of the kernels may be too difficult to reach with the teeth or fingernails, and some individuals use sticks to remove these remains, instead of pounding the nut further with the hammer as other individuals do:[21] a relatively rare combination of using two different tools. Hammers for opening nuts may be either wood or stone.

Chimpanzees in the Nimba Mountains of Guinea, Africa, use both stone and wooden cleavers, as well as stone anvils, to chop up and reduce Treculia fruits into smaller bite-sized portions. These fruits, which can be the size of a volleyball and weigh up to 8.5 kg, are hard and fibrous. But, despite lacking a hard outer shell, they are too large for a chimpanzee to get its jaws around and bite into. Instead, the chimpanzees use a range of tools to chop them into smaller pieces. This is the first account of chimpanzees using a pounding tool technology to break down large food items into bite-sized chunks rather than just extracting it from other unobtainable sources such as baobab nuts. It is also the first time wild chimpanzees have been found to use two distinct types of percussive technology, i.e. movable cleavers against a non-movable anvil, to achieve the same goal. Neighbouring chimpanzees in the nearby region of Seringbara do not process their food in this way, indicating how tool use among apes is culturally learnt.[35]

- Collecting water

When chimpanzees cannot reach water that has formed in hollows high up inside trees, they have been observed taking a handful of leaves, chewing them, and dipping this "sponge" into the pool to suck out the water.[34] Both bonobos and chimpanzees have also been observed making "sponges" out of leaves and moss that suck up water and are used as grooming tools.[36]

Orangutans

Orangutans (genus Pongo) were first observed using tools in the wild in 1994 in the northwest corner of Sumatra.[37] As with the chimpanzees, orangutans use tools made from branches and leaves to scratch, scrape, wipe, sponge, swat, fan, hook, probe, scoop, pry, chisel, hammer, cover, cushion and amplify. They will break off a tree branch that is about 30 cm long, snap off the twigs, fray one end and then use the stick to dig in tree holes for termites.[23][38] Sumatran orangutans use a variety of tools—up to 54 types for extracting insects or honey, and as many as 20 types for opening or preparing fruits such as the hard to access Neesia Malayana.[39] They also use an 'autoerotic tool'—a stick which they use to stimulate the genitals and masturbate (both male and female).[40][41] In parts of Borneo, orangutans use handfuls of leaves as napkins to wipe their chins while orangutans in parts of Sumatra use leaves as gloves, helping them handle spiny fruits and branches, or as seat cushions in spiny trees.[42] There have been reports that individuals in both captivity and in the wild use tools held between the lips or teeth, rather than in the hands.[43] In captivity, orangutans have been taught to chip stone handaxes.[44][45]

Orangutans living in Borneo scavenge fish that wash up along the shore and scoop catfish out of small ponds for fresh meals. Over two years, anthropologist Anne Russon saw several animals on these forested islands learn on their own to jab at catfish with sticks, so that the panicked prey would flop out of ponds and into the orangutan's waiting hands.[46] Although orangutans usually fished alone, Russon observed pairs of apes catching catfish on a few occasions.[47] On the island of Kaja in Borneo, a male orangutan was observed using a pole apparently trying to spear or bludgeon fish. This individual had seen humans fishing with spears. Although not successful, he was later able to improvise by using the pole to catch fish already trapped in the locals' fishing lines.[48]

Sumatran orangutans use sticks to acquire seeds from a particular fruit.[49] When the fruit of the Neesia tree ripens, its hard, ridged husk softens until it falls open. Inside are seeds that are highly desirable to the orangutans, but they are surrounded by fibreglass-like hairs that are painful if eaten. A Neesia-eating orangutan will select a 12 cm stick, strip off the bark, and then carefully collect the hairs with it. Once the fruit is safe, the ape will eat the seeds using the stick or its fingers.[38] Sumatran orangutans will use a stick to poke a bees' nest wall, move it around and catch the honey.[38]

Orangutans have been observed using sticks to apparently measure the depth of water. It has been reported that orangutans use tools for a wide range of purposes including using leaves as protective gloves or napkins, using leafy branches to swat insects or gather water, and building sun or rain covers above the nests used for resting.[50] It has been reported that a Sumatran orangutan used a large leaf as an umbrella in a tropical rainstorm.[38]

Orangutans produce an alarm call known as a "kiss squeak" when they encounter a predator like a snake or a human. Sometimes, orangutans will strip leaves from a branch and hold them in front of their mouth when making the sound. It has been found this lowers the maximum frequency of the sound i.e. makes it deeper, and in addition, smaller orangutans are more likely to use the leaves. It has been suggested they use the leaves to make themselves sound bigger than they really are, the first documented case of an animal using a tool to manipulate sound.[51]

Gorillas

There are few reports of gorillas using tools in the wild.[52] Western lowland gorillas (Gorilla gorilla gorilla) have been observed using sticks to apparently measure the depth of water and as "walking sticks" to support their posture when crossing deeper water.[53] An adult female used a detached trunk from a small shrub as a stabilizer during food gathering, and another used a log as a bridge. One possible explanation for the absence of observed tool use in wild gorillas is that they are less dependent on foraging techniques that require the use of tools, since they exploit food resources differently from chimpanzees. Whereas chimpanzees and orangutans feeding involves tools such as hammers to crack open nuts and sticks to fish for termites, gorillas access these foods by breaking nuts with their teeth and smashing termite mounds with their hands.[54]

Captive western lowland gorillas have been observed to threaten each other with sticks and larger pieces of wood, while others use sticks for hygienic purposes. Some females have attempted to use logs as ladders.[55] In another group of captive gorillas, several individuals were observed throwing sticks and branches into a tree, apparently to knock down leaves and seeds.[56] Gorillas at Prague zoo have used tools in several ways, including using wood wool as "slippers" when walking on the snow or to cross a wet section of the floor.[25]

Monkeys

Tool use has been observed in capuchin monkeys both in captivity and in their natural environments. In a captive environment, capuchins readily insert a stick into a tube containing viscous food that clings to the stick, which they then extract and lick.[57] Capuchins also use a stick to push food from the center of a tube retrieving the food when it reaches the far end,[58] and as a rake to sweep objects or food toward themselves.[59] The black-striped capuchin (Sapajus libidinosus) was the first non-ape primate for which tool use was documented in the wild; individuals were observed cracking nuts by placing them on a stone anvil and hitting them with another large stone (hammer).[60] Similar hammer-and-anvil use has been observed in other wild capuchins including robust capuchin monkeys (genus Sapajus)[60][61][62][63][64] It may take a capuchin up to 8 years to master this skill.[65] The monkeys often transport hard fruits, stones, nuts and even oysters to an anvil for this purpose.[66] Capuchins also use stones as digging tools for probing the substrate and sometimes for excavating tubers.[9] Wild black-striped capuchin use sticks to flush prey from inside rock crevices.[9] Robust capuchins are also known at times to rub defensive secretions from arthropods over their bodies before eating them;[61] such secretions are believed to act as natural insecticides.

Tool use by baboons in the wild was mentioned by Charles Darwin in his book The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex.[67]

Brehm states, on the authority of the well-known traveller Schimper, that in Abyssinia when the baboons belonging to one species (C. gelada) descend in troops from the mountains to plunder the fields, they sometimes encounter troops of another species (C. hamadryas), and then a fight ensues. The Geladas roll down great stones, which the Hamadryas try to avoid...

Darwin continued:

Brehm, when accompanying the Duke of Coburg-Gotha, aided in an attack with fire-arms on a troop of baboons in the pass of Mensa in Abyssinia. The baboons in return rolled so many stones down the mountain, some as large as a man's head, that the attackers had to beat a hasty retreat; and the pass was actually for a time closed against the caravan.

These rather anecdotal reports of stone throwing by baboons have been corroborated by more recent research on chacma baboon (Papio ursinus) troops living on the desert floor of the Kuiseb Canyon in South West Africa. Stoning by these baboons is done from the rocky walls of the canyon where they sleep and retreat when they are threatened. Stones are lifted with one hand and dropped over the side. The stones tumble down the side of the cliff or falls directly to the canyon floor. The researchers recorded 23 such incidents involving the voluntary release of 124 stones.[68]

A subadult male from a captive group of Guinea baboons (Papio papio) learned, by trial-and-error, to use a tool to rake in food. He then used the tool 104 times over 26 days, thereby providing the group with most of its food.[69]

In the wild, mandrills have been observed to clean their ears with modified tools. Scientists filmed a large male mandrill at Chester Zoo stripping down a twig, apparently to make it narrower, and then using the modified stick to scrape dirt from underneath its toenails.[24]

In Thailand and Myanmar, crab-eating macaques use stone tools to open nuts, oysters and other bivalves, and various types of sea snails (nerites, muricids, trochids, etc.) along the Andaman sea coast and offshore islands.[70] A troop of wild macaques which regularly interact with humans have learnt to remove hairs from the human's heads, and use the hair to floss their teeth.[71]

Elephants

Elephants show an ability to manufacture and use tools with their trunk and feet. Both wild and captive Asian elephants (Elephas maximus) use branches to swat flies or scratch themselves.[72][73] Eight of 13 captive Asian elephants, maintained under a naturalistic environment, modified branches and switched with the altered branch, indicating this species is capable of the more rare behaviour of tool manufacture. There were different styles of modification of the branches, the most common of which was holding the main stem with the front foot and pulling off a side branch or distal end with the trunk. Elephants have been observed digging holes to drink water, then ripping bark from a tree, chewing it into the shape of a ball thereby manufacturing a "plug" to fill in the hole, and covering it with sand to avoid evaporation. They would later go back to the spot to drink.

Asian elephants may use tools in insightful problem solving. A captive male was observed moving a box to a position where it could be stood upon to reach food that had been deliberately hung out of reach.[74][75]

Elephants have also been known to drop large rocks onto an electric fence to either ruin the fence or cut off the electricity.[76]

Cetaceans

A community of Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops sp.) in Shark Bay, Western Australia, made up of approximately 41-54 animals, are known to use conical sponges (Echinodictyum mesenterinum) as tools while foraging.[78][79] This behavior, termed “sponging,” occurs when a dolphin breaks off a sponge and wears it over its rostrum while foraging on the seafloor.[79] Sponging behavior typically begins in the second year of life.[80] During sponging, dolphins mainly target fish that lack swimbladders and burrow in the substrate.[77] Therefore, the sponge may be used to protect their rostrums as they forage in a niche where echolocation and vision are less effective hunting techniques.[77][81] Dolphins tend to carry the same sponge for multiple surfacings but sometimes change sponges.[79] Spongers typically are more solitary, take deeper dives, and spend more time foraging than non-spongers.[79] Despite these costs, spongers have similar calving success to non-spongers.[79]

There is evidence that both ecological and cultural factors predict which dolphins use sponges as tools. Sponging occurs more frequently in areas with higher distribution of sponges, which tends to occur in deeper water channels.[78][82] Sponging is heavily sex-biased to females.[78] Genetic analyses suggest that all spongers are descendants of a single matriline, suggesting cultural transmission of the use of sponges as tools.[83] Sponging may be socially learned from mother to offspring.[84][85] Social grouping behavior suggests homophily (the tendency to associate with similar others) among dolphins that share socially learned skills such as sponge tool use.[86] Sponging has only been observed in Shark Bay.

Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphins in Shark Bay have also been observed carrying conch shells. In this behavior, dolphins insert their rostrum into the shell’s aperture. Although this behavior is rare, it appears to be used for foraging. Dolphins appear to use the conch shells to scoop fish from the substrate then carry the shell to retrieve the fish near the surface.[87]

Sea otters

Under each foreleg, the sea otter (Enhydra lutris) has a loose pouch of skin that extends across the chest. In this pouch (preferentially the left side), the animal stores collected food to bring to the surface. This pouch also holds a rock, unique to the otter, that is used to break open shellfish and clams.[88] To open hard shells, it may pound its prey with both paws against the rock which it places on its chest. Furthermore, sea otters will use large stones to pry an abalone off its rock; they will hammer the abalone shell with observed rates of 45 blows in 15 seconds or 180 rpm, and do it in two–three dives. Releasing an abalone, which can cling to rock with a force equal to 4,000 times its own body weight, requires multiple dives by the otter.[89]

Other carnivores

Wild banded mongooses (Mungos mungo) regularly use anvils to open food items with a hard shell such as rhinoceros beetles, bird eggs, snail shells or pupating dung beetles. They use a range of anvils commonly including rocks and the stems of trees, but will also use the side-walls of gullys and even dried elephant dung. Pups as young as 2 months of age are already showing the behavioural patterns associated with using an anvil, however, successful smashing is usually shown in individuals older than 6 months of age.[90]

North American badgers (Taxidea taxus) hunt Richardson's ground squirrels (Spermophilus richardsonii). The most common hunting technique is excavation of burrow systems, but plugging of openings into ground-squirrel tunnels accounts for 5–23% of hunting actions. Badgers usually use soil from around the tunnel opening, or soil dragged 30–270 cm from a nearby mound to plug tunnels. The least common (6%), but most novel, form of plugging used by 1 badger involved movement of 37 objects from distances of 20–105 cm to plug openings into 23 ground-squirrel tunnels on 14 nights.[91]

In 2011, researchers at the Dingo Discovery and Research Centre in Melbourne, Australia, filmed a dingo manipulating a table and using this to get food.[92]

Moulting brown bears in Alaska have been observed using rocks to exfoliate.[93]

In birds

Tool use is found in at least thirty-three different families of birds.[8] According to Jones and Kamil's definition,[4] a Bearded vulture dropping a bone on a rock would not be considered using a tool since the rock cannot be seen as an extension of the body. However, the use of a rock manipulated using the beak to crack an ostrich egg would qualify the Egyptian vulture as a tool user. Many other species, including parrots, corvids and a range of passerines, have been noted as tool users.[94]

Many birds (and other animals) build nests.[96] It can be argued that this behaviour constitutes tool use according to the definitions given above; the birds "carry objects (twigs, leaves) for future use", the shape of the formed nest prevents the eggs from rolling away and thereby "extends the physical influence realized by the animal", and the twigs are bent and twisted to shape the nest, i.e. "modified to fit a purpose". The complexity of bird nests varies markedly, perhaps indicating a range in the sophistication of tool use. For example, compare the highly complex structures of weaver birds to the simple mats of herbaceous matter with a central cup constructed by gulls, and it is noteworthy that some birds do not build nests, e.g. emperor penguins. The classification of nests as tools has been disputed on the basis that the completed nest, or burrow, is not held or manipulated.[2]

Woodpecker finches

Perhaps the best known and most studied example of an avian tool user is the woodpecker finch (Camarhynchus pallidus) from the Galápagos Islands. If the bird uncovers prey in bark which is inaccessible, the bird then flies off to fetch a cactus spine which it may use in one of three different ways: as a goad to drive out an active insect (without necessarily touching it): as a spear with which to impale a slow-moving larva or similar animal; or as an implement with which to push, bring towards, nudge or otherwise manoeuvre an inactive insect from a crevice or hole. Tools that are not exactly fitting the purpose are worked by the bird and adapted for the function thus making the finch a "tool maker" as well as a "tool user". Some individuals have been observed to use a different type of tool with novel functional features such as barbed twigs from blackberry bushes, a plant that is not native to the islands. The twigs were first modified by removing side twigs and leaves and then used such that the barbs helped drag prey out of tree crevices.[8]

There is a genetic predisposition for tool use in this species, which is then refined by individual trial-and-error learning during a sensitive phase early in development. This means that, rather than following a stereotypical behavioural pattern, tool use can be modified and adapted by learning.

The importance of tool use by woodpecker finches species differs between vegetation zones. In the arid zone, where food is limited and hard to access, tool use is essential, especially during the dry season. Up to half of the finches' prey is acquired with the help of tools, making them even more routine tool users than chimpanzees. The tools allow them to extract large, nutritious insect larvae from tree holes, making tool use more profitable than other foraging techniques. In contrast, in the humid zone, woodpecker finches rarely use tools, since food availability is high and prey is more easily obtainable. Here, the time and energy costs of tool use would be too high.[8]

There have been reported cases of woodpecker finches brandishing a twig as a weapon.[14]

Corvids

Corvids are a family of birds characterised by relatively large brains, remarkable behavioural plasticity (especially highly innovative foraging behaviour) and well-developed cognitive abilities.[8]

New Caledonian crow

New Caledonian crows (Corvus moneduloides) are perhaps the most studied corvid with respect to tool-use.

In the wild, they have been observed using sticks as tools to extract insects from tree bark.[97][98] The birds poke the insects or larvae until they bite the stick in defence and can then be drawn out. This "larva fishing" is very similar to the "termite fishing" practised by chimpanzees. In the wild, they also manufacture tools from twigs, grass stems or similar plant structures, whereas captive individuals have been observed to use a variety of materials, including feathers and garden wire. Stick tools can either be non-hooked—being more or less straight and requiring only little modification—or hooked. Construction of the more complex hooked tools typically involves choosing a forked twig from which parts are removed and the remaining end is sculpted and sharpened. New Caledonian crows also use pandanus tools, made from barbed leaf edges of screw pines (Pandanus spp.) by precise ripping and cutting although the function of the pandanus tools is not understood.[99]

While young birds in the wild normally learn to make stick tools from elders, a laboratory New Caledonian crow named "Betty" was filmed spontaneously improvising a hooked tool from a wire. It was known that this individual had no prior experience as she had been hand-reared.[100] New Caledonian crows have been observed to use an easily available small tool to get a less easily available longer tool, and then use this to get an otherwise inaccessible longer tool to get food that was out of reach of the shorter tools. One bird, "Sam", spent 110 seconds inspecting the apparatus before completing each of the steps without any mistakes. This is an example of sequential tool use, which represents a higher cognitive function compared to many other forms of tool use and is the first time this has been observed in non-trained animals. Tool use has been observed in a non-foraging context, providing the first report of multi-context tool use in birds. Captive New Caledonian crows have used stick tools to make first contact with objects that were novel and hence potentially dangerous, while other individuals have been observed using a tool when food was within reach but placed next to a model snake. It has been claimed "Their [New Caledonian crow] tool-making skills exceed those of chimpanzees and are more similar to human tool manufacture than those of any other animal."[8]

New Caledonian crows have also been observed performing tool use behaviour that had hitherto not been described in non-human animals. The behaviour is termed "insert-and-transport tool use". This involves the crow inserting a stick into an object and then walking or flying away holding both the tool and object on the tool.[101]

Hawaiian crow

Captive individuals of the critically endangered Hawaiian crow (Corvus hawaiiensis) use tools to extract food from holes drilled in logs. The juveniles exhibit tool use without training or social learning from adults. As 104 of the 109 surviving members of the species were tested, it is believed to be a species-wide ability.[102][103]

Others

Other corvid species, such as rooks (Corvus frugilegus), can also make and use tools in the laboratory, showing a degree of sophistication similar to that of New Caledonian crows.[8] While not confirmed to have used tools in the wild, captive blue jays (Cyanocitta cristata) have been observed using strips of newspaper as tools to obtain food.[104][105]

A wild American crow (Corvus brachyrhynchos) has been observed to modify and use a piece of wood as a probe.[106] Green jays (Cyanocorax yncas) have been observed using sticks as tools to extract insects from tree bark,[107] Large-billed crows in urban Japan have been filmed using an innovative technique to crack hard-shelled nuts by dropping them onto cross walks (pedestrian crossings) and letting them be run over and cracked by cars. They then retrieve the cracked nuts when the cars are stopped at the red light.[108] In some towns in America, crows drop walnuts onto busy streets so that the cars will crack the nuts.[109]Hooded crows (Corvus cornix) use bait to catch fish.[110] Individuals (who may have observed fish being fed bread by humans) will place the bread in the water to attract fish.[14]

Common ravens (Corvus corax) are one of only a few species who make their own toys. They have been observed breaking off twigs to play with socially.[111] A corvid has been filmed sliding repeatedly down a snow-covered roof while balancing on a lid or tray.[112][113][114] Another incidence of play in birds has been filmed showing a corvid playing with a table tennis ball in partnership with a dog, a rare example of tool use for the purposes of play.[115] Blue jays, like other corvids, are highly curious and are considered intelligent birds. Young blue jays playfully snatch brightly coloured or reflective objects, such as bottle caps or pieces of aluminium foil, and carry them around until they lose interest.

Warblers

_Nest_in_Hyderabad%2C_AP_W_IMG_7248.jpg)

The tailorbird (genus Orthotomus) takes a large growing leaf (or two or more small ones) and with its sharp bill pierces holes into opposite edges. It then grasps spider silk, silk from cocoons, or plant fibres with its bill, pulls this "thread" through the two holes, and knots it to prevent it from pulling through (although the use of knots is disputed[116]). This process is repeated several times until the leaf or leaves forms a pouch or cup in which the bird then builds its nest.[14][117] The leaves are sewn together in such a way that the upper surfaces are outwards making the structure difficult to see. The punctures made on the edge of the leaves are minute and do not cause browning of the leaves, further aiding camouflage. The processes used by the tailorbird have been classified as sewing, rivetting, lacing and matting. Once the stitch is made, the fibres fluff out on the outside and in effect they are more like rivets. Sometimes the fibres from one rivet are extended into an adjoining puncture and appear more like sewing. There are many variations in the nest and some may altogether lack the cradle of leaves. It is believed that only the female performs this sewing behaviour.[116] The Latin binomial name of the common tailorbird, Orthotomus sutorius, means "straight-edged" "cobbler" rather than tailor.[118] Some birds of the genus Prinia also practice this sewing and stitching behaviour.[119]

Parrots

Kea, a highly inquisitive New Zealand mountain parrot, have been filmed stripping twigs and inserting them into gaps in box-like stoat traps to trigger them. Apparently, the kea's only reward is the banging sound of the trap being set off.[120] In a similarly rare example of tool preparation, a captive Tanimbar corella (Cacatua goffiniana) was observed breaking off and "shaping" splinters of wood and small sticks to create rakes that were then used to retrieve otherwise unavailable food items on the other side of the aviary mesh.[121][122] This behaviour has been filmed.

Many owners of household parrots have observed their pets using various tools to scratch various parts of their bodies. These tools include discarded feathers, bottle caps, popsicle sticks, matchsticks, cigarette packets and nuts in their shells.[14]

Hyacinth macaws (Anodorhynchus hyacinthinus) have been repeatedly observed to use tools when breaking open nuts, for example, pieces of wood being used as a wedge. Several birds have wrapped a piece of leaf around a nut to hold it in place. This behaviour is also shown by palm cockatoos (Probosciger aterrimus). It seems that the hyacinth macaw has an innate tendency to use tools during manipulation of nuts, as naïve juveniles tried out a variety of objects in combination with nuts.[8]

Egyptian vultures

When an Egyptian vulture (Neophron percnopterus) encounters a large egg, it takes a stone into its beak and forcefully throws it at the egg until the shell is broken, usually taking a few minutes. This behaviour, first reported in 1966,[123] seems to be largely innate and is displayed by naïve individuals. Its origin could be related to the throwing of eggs and, interestingly, rounded (egg-like) stones are preferred to jagged ones.[124]

In a small population in Bulgaria, Egyptian vultures use twigs to collect sheep wool for padding their nests. Although both twigs and wool can serve as nesting material, this appears to be deliberate tool use. The birds approached bits of discarded wool with a twig in their beak, which was then either used as a rake, to gather the wool into heaps, or to roll up the wool. Interestingly, wool was collected only after shearing or simulated shearing of sheep had taken place, but not after wool had simply been deposited in sheep enclosures.[125]

Brown-headed nuthatches

Brown-headed nuthatches (Sitta pusilla) have been observed to methodically use bark pieces to remove other flakes of bark from a tree. The birds insert the bark piece underneath an attached bark scale, using it like a wedge and lever, to expose hiding insects. Occasionally, they reuse the same piece of bark several times and sometimes even fly short distances carrying the bark flake in their beak. The evolutionary origin of this tool use might be related to these birds frequently wedging seeds into cracks in the bark to hammer them open with their beak, which can lead to bark coming off.

Brown-headed nuthatches have also used a bark flake for concealing a seed cache.[8]

Gulls

Seagulls have been known to drop live oyster shells on paved and hard surfaces so that cars can drive over them and break the shell. So many get dropped that it is difficult to drive safely near some waterways. Certain species (e.g. the herring gull) have exhibited tool use behavior, using pieces of bread as bait to catch goldfish, for example.[18]

Owls

Burrowing owls (Athene cunicularia) frequently collect mammalian dung, which they use as a bait to attract dung beetles, a major item of prey.[126]

Herons

The green heron (Butorides virescens) and its sister species the striated heron (Butorides striata) have been recorded using food (bread crusts), insects, leaves, and other small objects as bait to attract fish, which they then capture and eat.[127]

In invertebrates

In cephalopods

At least four veined octopus (Amphioctopus marginatus) individuals were witnessed retrieving coconut shells, manipulating them, stacking them, transporting them some distance (up to 20 metres), and then reassembling them to use as a shelter.[128] The octopuses use coconut shells discarded by humans which have eventually settled in the ocean. They probe their arms down to loosen the mud, then rotate the shells out. After turning the shells so the open side faces upwards, the octopuses blow jets of mud out of the bowl before extending their arms around the shell—or if they have two halves, stacking them first, one inside the other. They then stiffen their legs and move away in a manner which has been called "stilt-walking". The octopuses eventually use the shells as a protective shelter in areas where little other shelter exists. If they just have one half, they simply turn it over and hide underneath. But if they are lucky enough to have retrieved two halves, they assemble them back into the original closed coconut form and sneak inside. This behaviour has been filmed. The authors of the research article claimed this behaviour falls under the definition of tool use because the shells are carried for later use. However, this argument remains contested by a number of other biologists who state that the shells actually provide continuous protection from abundant bottom-dwelling predators in their home range.

Octopuses deliberately place stones, shells and even bits of broken bottle to form a wall that constricts the aperture to the den, a type of tool use.[129]

In laboratory studies, Octopus mercatoris, a small pygmy species of octopus, has been observed to block its lair using a plastic Lego brick.[12]

Smaller individuals of the common blanket octopus (Tremoctopus violaceus) hold the tentacles of the Portuguese man o' war, to whose poison they are immune, both as protection and as a method of capturing prey.[130]

In insects

Ants of the species Conomyrma bicolor pick up stones and other small objects with their mandibles and drop them down the vertical entrances of rival colonies, allowing workers to forage for food without competition.[131]

Several species of ants are known to use substrate debris such as mud and leaves to transport water to their nest. A study in 2017 reported that when two species of Aphaenogaster ant are offered natural and artificial objects as tools for this activity, they choose items with a good soaking capacity. The ants develop a preference for artificial tools that cannot be found in their natural environment, indicating plasticity in their tool-use behaviour.[132]

Hunting wasps of the genus Prionyx use weights (such as compacted sediment or a small pebble) to settle sand surrounding a recently provisioned burrow containing eggs and live prey in order to camouflage and seal the entrance. The wasp vibrates its wing muscles with an audible buzz while holding the weight in its mandibles, and applies the weight to the sand surrounding its burrow, causing the sand to vibrate and settle. Another hunting wasp, Ammophila, uses pebbles to close burrow entrances.[133]

In fish

Several species of wrasses have been observed using rocks as anvils to crack bivalve (scallops, urchins and clams) shells. It was first filmed in an orange-dotted tuskfish (Choerodon anchorago) in 2009 by Giacomo Bernardi. The fish fans sand to unearth the bivalve, takes it into its mouth, swims several metres to a rock which it uses as an anvil by smashing the mollusc apart with sideward thrashes of the head. This behaviour has been recorded in a blackspot tuskfish (Choerodon schoenleinii) on Australia's Great Barrier Reef, yellowhead wrasse (Halichoeres garnoti) in Florida and a six-bar wrasse (Thalassoma hardwicke) in an aquarium setting. These species are at opposite ends of the phylogenetic tree in this family, so this behaviour may be a deep-seated trait in all wrasses.[134]

It has been reported that freshwater stingrays use water as a tool by manipulating their bodies to direct a flow of water and extract food trapped amongst plants.[135]

Prior to laying their eggs on a vertical rock face, male and female whitetail major damselfish clean the site by sand-blasting it. The fish pick up sand in their mouths and spit it against the rock face. Then they fan the area with their fins. Finally they remove the sand grains that remain stuck to the rock face by picking them off with their mouths.[136]

Banded acara, (Bujurquina vittata), South American cichlids, lay their eggs on a loose leaf. The male and female of a mating pair often “test” leaves before spawning: they pull and lift and turn candidate leaves, possibly trying to select leaves that are easy to move. After spawning, both parents guard the eggs. When disturbed, the parent acara often seize one end of the egg-carrying leaf in their mouth and drag it to deeper and safer locations.[137]

Archerfish are found in the tropical mangrove swamps of India and Australasia. They approach the surface, take aim at insects that sit on plants above the surface, squirt a jet of water at them, and grab them after the insects have been knocked off into the water. The jet of water is formed by the action of the tongue, which presses against a groove in the roof of the mouth. Some archerfish can hit insects up to 1.5 m above the water surface. They use more water, which gives more force to the impact, when aiming at larger prey. Triggerfish (Pseudobalistes fuscus) blow water to turn sea urchins over and expose their more vulnerable ventral side.[138] Whether these later examples can be classified as tool use depends on which definition is being followed because there is no intermediate or manipulated object, however, they are examples of highly specialized natural adaptations.

In reptiles

Tool use by American alligators and mugger crocodiles has been documented. During the breeding season, birds such as herons and egrets look for sticks to build their nests. Alligators and crocodiles collect sticks to use as bait to catch birds. The crocodilian positions itself near a rookery, partially submerges with the sticks balanced on its head, and when a bird approaches to take the stick, it springs its trap. This stick displaying strategy is the first known case of a predator not only using an object as a lure, but also taking into account the seasonal behavior of its prey.[139][140]

See also

- Animal cognition

- Bird intelligence

- Cephalopod intelligence

- Cetacean intelligence

- Elephant intelligence

- Structures built by animals

References

- ↑ Beck, B., (1980). Animal Tool Behaviour: The Use and Manufacture of Tools by Animals Garland STPM Pub.

- 1 2 3 Shumaker, R.W., Walkup, K.R. and Beck, B.B., (2011). Animal Tool Behavior: The Use and Manufacture of Tools by Animals Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore

- ↑ Finn, Julian K.; Tregenza, Tom; Norman, Mark D. (2009). "Defensive tool use in a coconut-carrying octopus". Curr. Biol. 19 (23): R1069–R1070. PMID 20064403. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2009.10.052.

- 1 2 Jones, T. B.; Kamil, A. C. (1973). "Tool-making and tool-using in the northern blue jay". Science. 180 (4090): 1076–1078. PMID 17806587. doi:10.1126/science.180.4090.1076.

- ↑ Tom L. Beauchamp; R.G. Frey, eds. (2011). The Oxford Handbook of Animal Ethics. Oxford University Press. p. 232. ISBN 978-0195-3719-63.

- ↑ Lawick-Goodall, J.V., (1970). Tool using in primates and other vertebrates in Lehrman, D.S, Hinde, R.A. and Shaw, E. (Eds) Advances in the Study of Behaviour, Vol. 3. Academic Press.

- ↑ "Video of a bird apparently using bread as bait to catch fish". Retrieved October 7, 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "Tool use in birds". Map Of Life. Retrieved July 23, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 Mannu, M.; Ottoni, E.B. (2009). "The enhanced tool-kit of two groups of monkeys in the Caatinga: tool making, associative use, and secondary tools". American Journal of Primatology. 71 (3): 242–251. PMID 19051323. doi:10.1002/ajp.20642.

- ↑ Mulcahy, N.J.; Call, J.; Dunbar, R.I.B. (2005). "Gorillas (Gorilla gorilla) and orangutans (Pongo pygmaeus) encode relevant problem features in a tool-using task". Journal of Comparative Psychology. 119: 23–32. doi:10.1037/0735-7036.119.1.23.

- ↑ Pierce, J.D. (1986). "A review of tool use in insects". The Florida Entomologist. 69: 95–104. doi:10.2307/3494748.

- 1 2 Oinuma, C., (2008). Octopus mercatoris response behavior to novel objects in a laboratory setting: Evidence of play and tool use behavior? In, Octopus Tool Use and Play Behavior.

- ↑ Bjorklung, David F.; Gardiner, Amy K. (2011). "Object Play and Tool Use: Developmental and Evolutionary Perspectives". In Anthony D. Pellegrini. The Oxford Handbook of the Development of Play. Oxford University Press. p. 153. ISBN 978-0195-39300-2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Boswall, J. (1977). Tool-using by birds and related behaviour. Avicultural Magazine, 83: 88-97

- ↑ Weathers, Wesley (1983). Birds of Southern California's Deep Canyon. University of California Press. p. 189. ISBN 978-052004-754-9.

- ↑ Ghoshal, Kingshuck (ed.). DK Eyewitness Books: Predator. New York: DK Publishing. p. 54. ISBN 978-0-7566-8267-5.

- ↑ Ehrlich, Dobkin & Wheye. "Stanford Birds: Tool Essays". Stanford University. Retrieved October 7, 2015.

- 1 2 Henry, Pierre-Yves; Jean-Christophe Aznar (June 2006). "Tool-use in Charadrii: Active Bait-Fishing by a Herring Gull". Waterbirds. 29 (2): 233–234. ISSN 1524-4695. doi:10.1675/1524-4695(2006)29[233:TICABB]2.0.CO;2.

- ↑ Hunt, Gavin R.; Gray, Russel D.; Taylor, Alex H. (2013). "Why is tool use rare in animals?". In Sanz, Crickette M.; Call, Josep; Boesch, Christophe. Tool Use in Animals: Cognition and Ecology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 91. ISBN 978-1-107-01119-9.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Tool use, hunting & other discoveries". The Jane Goodall Institute. Retrieved August 1, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Boesch, C. & Boesch, H. (1990). "Tool use and tool making in wild chimpanzees." (PDF). Folia Primatol. 54: 86–99. PMID 2157651. doi:10.1159/000156428.

- ↑ Boesch, Christophe; Boesch-Achermann, Hedwige (2000). The Chimpanzees of the Taï Forest: Behavioural Ecology and Evolution. Oxford University Press. p. 192. ISBN 978-01985-0508-2.

- 1 2 Van Schaik, C.; Fox, E.; Sitompul, A. (1996). "Manufacture and use of tools in wild Sumatran orangutans". Naturwissenschaften. 83: 186–188. doi:10.1007/s001140050271.

- 1 2 Gill, Victoria (July 22, 2011). "Mandrill monkey makes 'pedicuring' tool". BBC. Retrieved August 11, 2013.

- 1 2 Vancatova, M. (2008). "Gorillas and Tools - Part I". Retrieved August 4, 2013.

- 1 2 "Bonobos". ApeTag. 2010. Retrieved August 3, 2013.

- ↑ Gruber, T.; Clay, Z.; Zuberbühler, K. (2010). "A comparison of bonobo and chimpanzee tool use: evidence for a female bias in the Pan lineage" (PDF). Animal Behaviour. 80: 1023–1033. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2010.09.005.

- ↑ Sophie A. de Beaune; Frederick L. Coolidge; Thomas Wynn, eds. (2009). Cognitive Archaeology and Human Evolution. Cambridge University Press. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-52176-9778.

- ↑ Raffaele, Paul (2011). Among the Great Apes: Adventures on the Trail of Our Closest Relatives. Harper. p. 109. ISBN 9780061671845.

- ↑ Roach, J. (2007). "Chimps use "spears" to hunt mammals, study says". National Geographic News. Retrieved August 1, 2013.

- ↑ "Chimpanzees 'hunt using spears'". BBC. February 22, 2007. Retrieved August 11, 2013.

- ↑ Shipman, Pat (2011). The Animal Connection: A New Perspective on What Makes Us Human. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 95. ISBN 9780393082227.

- ↑ Raffaele, Paul (2011). Among the Great Apes: Adventures on the Trail of Our Closest Relatives. Harper. p. 83. ISBN 978-0061671-84-5.

- 1 2 "Study corner - tool use". The Jane Goodall Institute. Retrieved August 1, 2013.

- ↑ Walker, M. (December 24, 2009). "Chimps use cleavers and anvils as tools to chop food". BBC. Retrieved August 11, 2013.

- ↑ Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University. Dept. of Anthropology (1995). Symbols. Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology. p. 5.

- ↑ "Just Hangin' on: Orangutan tools". Nature. Retrieved August 5, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 "Sumatran orangutans". OrangutanIslands.com. Retrieved August 2, 2013.

- ↑ Julian Oliver Caldecott; Lera Miles, eds. (2005). World Atlas of Great Apes and Their Conservation. University of California Press. p. 189. ISBN 978-05202-4633-1.

- ↑ http://www.aim.uzh.ch/Research/orangutannetwork/CultureList.html

- ↑ Anne E. Russon, Carel P. van Schaik, Purwo Kuncoro, Agnes Ferisa, Dwi P. Handayani and Maria A. van Noordwijk Innovation and intelligence in orangutans, Chapter 20 in Orangutans: Geographic Variation in Behavioral Ecology and Conservation, ed. Wich, Serge A., Oxford University Press, 2009 ISBN 978-0-19921-327-6, p.293

- ↑ "Orangutan behavior". Orangutan International Foundation. Retrieved August 5, 2013.

- ↑ O'Malley, R.C.; McGrew, W.C. (2000). "Oral tool use by captive orangutans (Pongo pygmaeus)". Folia Primatol. 71: 334–341. PMID 11093037. doi:10.1159/000021756.

- ↑ "Orangutan behavior". Orangutan Foundation International. Retrieved March 30, 2014.

- ↑ Davidson, I; McGrew, W.C. (2005). "Stone tools and the uniqueness of human culture" (PDF). Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute. 11 (4): 793–817. ISSN 1359-0987. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9655.2005.00262.x.

- ↑ Bower, Bruce (May 7, 2011). (subscription required)%5b%5bCategory:Pages containing links to subscription-only content%5d%5d "Borneo Orangs Fish for Their Dinner: Behavior Suggests Early Human Ancestors Were Piscivores" Check

|url=value (help). Science News. 179 (10): 16. doi:10.1002/scin.5591791014. - ↑ Bower, B. (April 18, 2011). "Orangutans use simple tools to catch fish". Wired. Retrieved August 5, 2013.

- ↑ "Orangutan attempts to hunt fish with spear". London: MailOnline. April 26, 2008. Retrieved August 1, 2013.

- ↑ John C. Mitani; Josep Call; Peter M. Kappeler; Ryne A. Palombit; Joan B. Silk, eds. (2012). The Evolution of Primate Societies. University of Chicago Press. p. 685. ISBN 978-0-2265-3173-1.

- ↑ "Evidence for orangutan culture". DailyNews. Retrieved August 2, 2013.

- ↑ Zielinski, S. (2009). "Orangutans use leaves to sound bigger". Retrieved August 5, 2013.

- ↑ Tetsurō Matsuzawa; Masaki Tomonaga, eds. (2006). Cognitive Development in Chimpanzees. 2006. p. 398. ISBN 978-44313-0248-3.

- ↑ Gross, L. (2005). "Wild gorillas handy with a stick". PLoS Biology. 3: e385. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0030385. Retrieved August 2, 2013.

- ↑ Breuer, T.; Ndoundou-Hockemba, M.; Fishlock, V. (2005). "First observation of tool use in wild gorillas". PLoS Biol. 3 (11): e380. PMC 1236726

. PMID 16187795. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0030380.

. PMID 16187795. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0030380. - ↑ Fontaine, B., Moisson, P.Y. and Wickings, E.J. (1995). "Observations of spontaneous tool making and tool use in a captive group of western lowland gorillas (Gorilla gorilla gorilla)". Retrieved June 8, 2014.

- ↑ Nakamichi, M. (July 1999). "Spontaneous use of sticks as tools by captive gorillas (Gorilla gorilla gorilla)". Primates, 40: 487-498. 40: 487–498. doi:10.1007/BF02557584. Retrieved June 8, 2014.

- ↑ Westergaard, G.C.; et al. (1998). "Why some capuchin monkeys (Cebus apella) use probing tools (and others do not)". Journal of Comparative Psychology. 112 (2): 207–211. PMID 9642788. doi:10.1037/0735-7036.112.2.207.

- ↑ Visalberghi, E; et al. ", (1995). Performance in a tool-using task by common chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes), bonobos (Pan paniscus), an orangutan (Pongo pygmaeus), and capuchin monkeys (Cebus apella)". Journal of Comparative Psychology. 109: 52–60. doi:10.1037/0735-7036.109.1.52.

- ↑ Cummins-Sebree, S.E.; Fragaszy, D. (2005). "Choosing and using tools: Capuchins (Cebus apella) use a different metric than tamarins (Saguinus oedipus)". Journal of Comparative Psychology. 119 (2): 210–219. PMID 15982164. doi:10.1037/0735-7036.119.2.210.

- 1 2 Fragaszy, D.; Izar, P.; Visalberghi, E.; Ottoni, E.B.; de Oliveira, M.G. (2004). "Wild capuchin monkeys (Cebus libidinosus) use anvils and stone pounding tools". American Journal of Primatology. 64 (4): 359–366. PMID 15580579. doi:10.1002/ajp.20085.

- 1 2 Alfaro, Lynch; Silva, J.S.; Rylands, A.B. (2012). "How different are robust and gracile capuchin monkeys? an argument for the use of Sapajus and Cebus". American Journal of Primatology. 74 (4): 273–286. doi:10.1002/ajp.222007.

- ↑ Ottoni, E.B.; Izar, P. (2008). "Capuchin monkey tool use: Overview and implications". Evolutionary Anthropology. 17: 171–178. doi:10.1002/evan.20185.

- ↑ Ottoni, E.B.; Mannu, M. (2001). "Semifree-ranging tufted capuchins (Cebus apella) spontaneously use tools to crack open nuts". International Journal of Primatology. 22: 347–358. doi:10.1023/A:1010747426841.

- ↑ Boinski, S., Quatrone, R. P. & Swartz, H. (2008). "Substrate and tool use by brown capuchins in Suriname: Ecological contexts and cognitive bases". American Anthropologist. 102 (4): 741–761. doi:10.1525/aa.2000.102.4.741.

- ↑ Life series. 2009. Episode 1. BBC.

- ↑ Visalberghi, E.; et al. (2009). "Selection of effective stone tools by wild bearded capuchin monkeys". Current Biology. 19 (3): 213–217. PMID 19147358. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2008.11.064.

- ↑ Darwin, C., (1871). The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex. John Murray, London, pp. 51-52

- ↑ Hamilton, W.J.; Buskirk, R.E.; Buskirk, W.H. (1975). "Defensive stoning by baboons". Nature. 256 (5517): 488–489. doi:10.1038/256488a0.

- ↑ Beck, B. (1973). "Observation learning of tool use by captive Guinea baboons (Papio papio)". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 38: 579–582. PMID 4632107. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330380270.

- ↑ Gumert, MD; Kluck, M.; Malaivijitnond, S. (2009). "The physical characteristics and usage patterns of stone axe and pounding hammers used by long-tailed macaques in the Andaman Sea region of Thailand". American Journal of Primatology. 71 (7): 594–608. PMID 19405083. doi:10.1002/ajp.20694.

- ↑ The One Show. Television programme broadcast by the BBC on March 26, 2014

- ↑ Hart, B. J.; Hart, L. A.; McCory, M.; Sarath, C. R. (2001). "Cognitive behaviour in Asian elephants: use and modification of branches for fly switching". Animal Behaviour. 62 (5): 839–47. doi:10.1006/anbe.2001.1815.

- ↑ Holdrege, Craig (Spring 2001). "Elephantine intelligence". In Context. The Nature Institute (5). Retrieved October 30, 2007.

- ↑ Foerder, P.; Galloway, M.; Barthel, T.; Moore, D.E. III; Reiss, D. (2011). "Insightful problem solving in an Asian elephant". PLOS ONE. 6 (8): e23251. PMC 3158079

. PMID 21876741. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0023251.

. PMID 21876741. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0023251. - ↑ "Elephants show smarts at National Zoo". The Washington Post. August 19, 2011.

- ↑ Poole, Joyce (1996). Coming of Age with Elephants. Chicago, Illinois: Trafalgar Square. pp. 131–133, 143–144, 155–157. ISBN 978-0-340-59179-6.

- 1 2 3 Patterson, E.M.; Mann, J. (2011). "The ecological conditions that favor tool use and innovation in wild bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops sp.).". PLOS ONE. 6 (e22243). PMC 3140497

. PMID 21799801. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0022243.

. PMID 21799801. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0022243. - 1 2 3 Smolker, R.A.; et al. (1997). "Sponge Carrying by Dolphins (Delphinidae, Tursiops sp.): A Foraging Specialization Involving Tool Use?". Ethology. 103 (6): 454–465. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0310.1997.tb00160.x.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Mann, J.B.; Sargeant, B.L.; Watson-Capps, J.J.; Gibson, Q.A.; Heithaus, M.R.; Connor, R.C.; Patterson, E (2008). "Why do dolphins carry sponges?". PLOS ONE. 3 (e3868). PMC 2587914

. PMID 19066625. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0003868.

. PMID 19066625. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0003868. - ↑ Mann, J.; Sargeant, B. (2003). "Like mother, like calf: the ontogeny of foraging traditions in wild Indian Ocean bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops sp.).". The biology of traditions: models and evidence: 236–266.

- ↑ Krutzen, M; Kreicker, S.; MacLeod, C.D.; Learmonth, J.; Kopps, A.M.; Walsham, P.; Allen, S.J. (2014). "Cultural transmission of tool use by Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops sp.) provides access to a novel foraging niche.". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 281: 20140374. PMC 4043097

. PMID 24759862. doi:10.1098/rspb.2014.0374.

. PMID 24759862. doi:10.1098/rspb.2014.0374. - ↑ Tyne, J.A.; Loneragan, N.R.; Kopps, A.M.; Allen, S.J.; Krutzen, M.; Bejder, L. (2012). "Ecological characteristics contribute to sponge distribution and tool use in bottlenose dolphins Tursiops sp.". Marine Ecology Progress Series. 444: 143–153. doi:10.3354/meps09410.

- ↑ Krutzen, M.J.; Mann, J.; Heithaus, M.R.; Connor, R.C.; Bedjer, L.; Sherwin, W.B. (2005). "Cultural transmission of tool use in bottlenose dolphins.". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 102: 8939–8943. PMC 1157020

. PMID 15947077. doi:10.1073/pnas.0500232102.

. PMID 15947077. doi:10.1073/pnas.0500232102. - ↑ Ackermann, C. (2008). Contrasting Vertical Skill Transmission Patterns of a Tool Use Behaviour in Two Groups of Wild Bottlenose Dolphins (Tursiops Sp.) as Revealed by Molecular Genetic Analyses.

- ↑ Sargeant, B.L.; Mann, J. (2009). "Developmental evidence for foraging traditions in wild bottlenose dolphins". Animal Behaviour. 78: 715–721. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2009.05.037.

- ↑ Mann, J.; Stanton, M.A.; Patterson, E.M.; Bienenstock, E.J.; Singh, L.O. (2012). "Social networks reveal cultural behaviour in tool-using dolphins.". Nature. 3: 980. PMID 22864573. doi:10.1038/ncomms1983.

- ↑ Allen, S.L.; Bejder, L.; Krutzen, M (2011). "Why do Indo‐Pacific bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops sp.) carry conch shells (Turbinella sp.) in Shark Bay, Western Australia?". Marine Mammal Science. 27: 449–454. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.2010.00409.x.

- ↑ Haley, D., ed. (1986). "Sea Otter". Marine Mammals of Eastern North Pacific and Arctic Waters (2nd ed.). Seattle, Washington: Pacific Search Press. ISBN 978-0-931397-14-1. OCLC 13760343.

- ↑ "Sea Otters, Enhydra lutris". Marinebio. Retrieved July 7, 2013.

- ↑ Müller, C.A. (2010). "Do anvil-using banded mongooses understand means-end relationships? A field experiment" (PDF). Animal Cognition. 13: 325–330. doi:10.1007/s10071-009-0281-5.

- ↑ Michener, Gail R. (2004). "Hunting techniques and tool use by North American badgers preying on Richardson's ground squirrels". Journal of Mammalogy. 85 (5): 1019–1027. JSTOR 1383835. doi:10.1644/BNS-102.

- ↑ "Dingoes use tools to solve novel problems". australiangeographic.com.au.

- ↑ Wild bear uses a stone to exfoliate

- ↑ Emery, N.J. (2006). "Cognitive ornithology: The evolution of avian intelligence" (PDF). Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B. 361: 23–43. PMC 1626540

. PMID 16553307. doi:10.1098/rstb.2005.1736.

. PMID 16553307. doi:10.1098/rstb.2005.1736. - ↑ E. A. Schreiber and Joanna Burger, eds. (2001). Biology of Marine Birds. CRC Press. p. 320. ISBN 978-142-003630-5.

- ↑ François Vuilleumier, ed. (2011). Birds of North America: Eastern Region. Dorling Kindersley. p. 18.

- ↑

- ↑ "Tool use in New CaledonianCrows". Behavioural Ecology Research Group. Retrieved February 19, 2013.

- ↑ Hunt, Gavin R.; Gray, Russell D. (February 7, 2004). "The Crafting of Hook Tools by Wild New Caledonian Crows". Proceedings: Biological Sciences. The Royal Society. 271 (Supplement 3): S88. JSTOR i388369. PMC 1809970

. PMID 15101428. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2003.0085.

. PMID 15101428. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2003.0085. - ↑ "Crow Makes Wire Hook to Get Food". nationalgeographic.com.

- ↑ Jacobs, I.F., von Bayern, A. and Osvath, M. (2016). "A novel tool-use mode in animals: New Caledonian crows insert tools to transport objects". Animal Cognition. 19 (6): 1249–1252. doi:10.1007/s10071-016-1016-z.

- ↑ Graef, A. (September 16, 2016). "Scientists discover tool use in brilliant Hawaiian crow". Care2. Retrieved September 18, 2016.

- ↑ Rutz, C.; et al. (2016). "Discovery of species-wide tool use in the Hawaiian crow". Nature. 537: 403–407. PMID 27629645. doi:10.1038/nature19103.

- ↑ Blue Jay. birds.cornell.edu

- ↑ Jones, Thony B. & Kamil, Alan C. (1973). "Tool-Making and Tool-Using in the Northern Blue Jay". Science. 180 (4090): 1076–1078. PMID 17806587. doi:10.1126/science.180.4090.1076.

- ↑ Caffrey, Carolee (2000). "Tool Modification and Use by an American Crow". Wilson Bull. 112 (2): 283–284. doi:10.1676/0043-5643(2000)112[0283:TMAUBA]2.0.CO;2.

- ↑ "Tool use by Green Jays" (PDF). Wilson Bulletin. 94 (4): 593–594. 1982.

- ↑ DK Publishing (2011). Animal Life. DK. p. 478. ISBN 978-0-75668-886-8.

- ↑ "Crows Using Automobiles as Nutcrackers". Retrieved March 29, 2014.

- ↑ "Bait-Fishing in Crows". Retrieved February 7, 2009.

- ↑ Heinrich, B., (1999). Mind of the Raven: Investigations and Adventures with Wolf-Birds pp 282. New York: Cliff Street Books. ISBN 978-0-06-093063-9

- ↑ Crowboarding on YouTube

- ↑ Goldman, Jason. "Snowboarding Crows: The Plot Thickens". Scientific American. Retrieved October 7, 2015.

- ↑ Heinrich & Smolker, ed. Bekoff & Byers (1998). Animal play: evolutionary, comparative and ecological perspectives (1. publ. ed.). Cambridge: University. ISBN 978-0-521-58656-6.

- ↑ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QqLU-o7N7Kw Dog and corvid playing with a ball

- 1 2 "Common Tailorbird". Answers.com. Retrieved July 22, 2013.

- ↑ "Tailorbird". Animal Planet. Retrieved July 22, 2013.

- ↑ "Common Tailorbird". 10,000 Birds. Retrieved July 22, 2013.

- ↑ "Prinia". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved July 22, 2013.

- ↑ Connor, S. (August 24, 2014). video "Sticky beak is New Zealand's tooled-up kea." Check

|url=value (help). Sunday Star Times. Retrieved August 25, 2014. - ↑ Auersperg, Alice M.I.; Szabo, Birgit; von Bayern, Auguste M.P.; Kacelnik, Alex (November 6, 2012). "Spontaneous innovation in tool manufacture and use in a Goffin’s cockatoo". Current Biology. 22 (21): R903–R904. PMID 23137681. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2012.09.002.

- ↑ Warwicker, M. (2012). "Cockatoo shows tool-making skills". BBC Nature. Retrieved July 21, 2013.

- ↑ Van Lawick-Goodall, J.; van Lawick, H. (1966). "Use of tools by the Egyptian Vulture, Neophron percnopterus". Nature. 212 (5069): 1468–1469. doi:10.1038/2121468a0.

- ↑ Thouless, C.R.; Fanshawe, J.H.; Bertram, B.C.R. (1989). "Egyptian Vultures Neophron percnopterus and Ostrich Struthio camelus eggs: The origins of stone-throwing behaviour". Ibis. 131: 9–15. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.1989.tb02737.x.

- ↑ Stoyanova, Y.; Stefanov, N.; Schmutz, J.K. (2010). "Twig used as a tool by the Egyptian Vulture (Neophron percnopterus)". Journal of Raptor Research. 44 (2): 154–156. doi:10.3356/JRR-09-20.1.

- ↑ Levey, DJ; Duncan, RS; Levins, CF (September 2, 2004). "Animal behaviour: Use of dung as a tool by burrowing owls". Nature. 431 (7004): 39. PMID 15343324. doi:10.1038/431039a. Retrieved October 25, 2016.

- ↑ "ITIS Report: Butorides virescens". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 28 August 2014.

- ↑ Finn, J.K., Tregenza, T. and M.D., (2009). Defensive tool use in a coconut-carrying octopus. Current Biology, doi:10.1016/j.cub.2009.10.052

- ↑ "Simple tool use in owls and cephalopods". Map Of Life. 2010. Retrieved July 23, 2013.

- ↑ Jones, E.C. (1963). "Tremoctopus violaceus uses Physalia tentacles as weapons". Science. 139 (3556): 764–766. doi:10.1126/science.139.3556.764.

- ↑ Michael H.J. Möglich & Gary D. Alpert (1979). "Stone dropping by Conomyrma bicolor (Hymenoptera: Formicidae): A new technique of interference competition". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 2 (6): 105–113. JSTOR 4599265. doi:10.1007/bf00292556.

- ↑ Maák, I., Lőrinczi, G., Le Quinquis, P., Módra, G., Bovet, D., Call, J. and d'Ettorre, P. (2017). "Tool selection during foraging in two species of funnel ants". Animal Behaviour. 123: 207–216. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2016.11.005.

- ↑ Sociobiology: The New Synthesis by Edward O. Wilson, p. 172; published 2000, by Harvard University Press (via Google Books)

- ↑ Bernardi, G. (2011). "The use of tools by wrasses (Labridae)." (PDF). doi:10.1007/s00338-011-0823-6. Retrieved July 7, 2013.

- ↑ Bourton, J. (January 13, 2010). "Clever stingray fish use tools to solve problems". BBC News. Retrieved July 8, 2013.

- ↑ Keenleyside, M.H.A., (1979). Diversity and Adaptation in Fish Behaviour, Springer-Verlag, Berlin.

- ↑ Keenleyside, M.H.A.; Prince, C. (1976). "Spawning-site selection in relation to parental care of eggs in Aequidens paraguayensis (Pisces: Cichlidae)". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 54: 2135–2139. doi:10.1139/z76-247.

- ↑ Reebs, S.G. (2011). "Tool use in fishes" (PDF). Retrieved July 7, 2013.

- ↑ Jason G. Goldman. "Crocodiles and their ilk may be smarter than they look". Washington Post. December 9, 2013

- ↑ "Crocodiles are cleverer than previously thought: Some crocodiles use lures to hunt their prey". ScienceDaily. December 4, 2013. Retrieved December 8, 2013.

Further reading

- Robert W. Shumaker; Kristina R. Walkup; Benjamin B. Beck (2011). Animal Tool Behavior: The Use and Manufacture of Tools by Animals. The Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Michael Henry Hansell (2005). Animal architecture. Oxford University Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-19-850752-9.

External links

- Chimpanzee making and using a termite "fishing rod"

- Chimpanzee using tool to break into beehive to get honey

- Crow making a tool by bending wire to snag food

- Various tool use by birds

- Fish using an anvil to break open prey

- Dolphin using a marine sponge to protect its rostrum

- Mandrill using a tool to clean under its nails

- New Caledonian crows picking up an object with a tool and transporting both