Tontine

| Look up tontine in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

A tontine (English pronunciation: /tɒntin/) is an investment plan for raising capital, devised in the 17th century and relatively widespread in the 18th and 19th centuries. It combines features of a group annuity and a lottery. Each subscriber pays an agreed sum into the fund, and thereafter receives an annuity. As members die, their shares devolve to the other participants, and so the value of each annuity increases. On the death of the last member, the scheme is wound up.

Tontines acquired an unsavory reputation, and were eventually prohibited or heavily restricted in many countries. However, in March 2017, The New York Times reported that tontines were getting fresh consideration as a way for people to get steady retirement income.[1]

History

The investment plan is named after Neapolitan banker Lorenzo de Tonti, who is credited with inventing it in France in 1653, although it has been suggested that he merely modified existing Italian investment schemes.[2] Tonti put his proposal to the French royal government, but after consideration it was rejected by the Parlement de Paris.[3] The first true tontine was therefore organised in the city of Kampen in the Netherlands in 1670. The French finally established a state tontine in 1689[3] (though it was not described by that name because Tonti had died in disgrace, about five years earlier). The English government organised a tontine in 1693.[4] Nine further government tontines were organised in France down to 1759; four more in Britain down to 1789; and others in the Netherlands and some of the German states. Those in Britain were not fully subscribed, and in general the British schemes tended to be less popular and successful than their continental counterparts.[5]

By the end of the 18th century, the tontine had fallen out of favour as a revenue-raising instrument with governments, but smaller-scale and less formal tontines continued to be arranged between individuals or to raise funds for specific projects throughout the 19th century, and, in modified form, to the present day.[1]

Concept

Each investor pays a sum into the tontine. Each investor then receives annual dividends on the capital invested. As each investor dies, his or her share is reallocated among the surviving investors. This process continues until only one investor survives. Each subscriber receives only dividends; the capital is never paid back.[6]

Strictly speaking, the transaction involves four different roles:[6]

- the government or corporate body which organizes the scheme, receives the loans and manages the capital

- the subscribers who provide the capital

- the shareholders who receive the annual dividends

- the nominees on whose lives the contracts are contingent

In most 18th and 19th-century schemes, parties 2 to 4 were the same individuals; but in a significant minority of schemes each initial subscriber-shareholder was permitted to invest in the name of another party (generally one of his or her own children), who would inherit that share on the subscriber's death.[6]

Sometimes the names in (4) were well-known people such as kings and queens. This eased the problem of death-verification and also reduced the risk of murder etc. to improve one's chances.

Because younger nominees clearly had a longer life expectancy, the 17th and 18th-century tontines were normally divided into several "classes" by age (typically in bands of 5, 7 or 10 years): each class effectively formed a separate tontine, with the shares of deceased members devolving to fellow-nominees within the same class.[6]

In a later variation, the capital devolves upon the last survivor, thus dissolving the trust and usually making the survivor very wealthy. This version has often been the plot device for mysteries and detective stories.

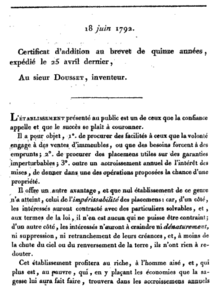

Patent

Financial inventions were patentable under French law from January 1791 until September 1792. In June 1792 a patent was issued to inventor F. P. Dousset for a new type of tontine in combination with a lottery.[7]

Uses and abuses

Louis XIV first made use of tontines in 1689 to fund military operations when he could not otherwise raise the money. The initial subscribers each put in 300 livres, and, unlike most later schemes, this one was run honestly; the last survivor, a widow named Charlotte Barbier, who died in 1726 at the age of 96, received 73,000 livres in her last payment.[8][9][10] The English government first issued tontines in 1693 to fund a war against France, part of the Nine Years' War.[4][10]

Tontines soon caused problems for their issuing governments, as the organisers tended to underestimate the longevity of the population. At first, tontine holders included men and women of all ages. However, by the mid-18th century, investors were beginning to understand how to game the system, and it became increasingly common to buy tontine shares for young children, especially for girls around the age of 5 (since girls lived longer than boys, and by which age they were less at risk of infant mortality). This created the possibility of significant returns for the shareholders, with significant losses for the organizers. As a result, tontine schemes were eventually abandoned, and by the mid-1850s tontines had been replaced by other investment vehicles, such as "penny policies", a predecessor of the 20th-century pension scheme.

Tontines became associated with life insurance in the United States in 1868 when Henry Baldwin Hyde of the Equitable Life Assurance Society introduced tontines as a means to sell more life insurance, and meet the demands of competition. When Equitable Life Assurance was establishing its business in Australia in the 1880s, an actuary of the Australian Mutual Provident Society criticised tontine insurance, calling it "an immoral contract" which "put a premium on murder".[11] In New Zealand at the time, one of the chief critics of tontines had been the government, which issued its own insurance.[12]

A property development tontine, The Victoria Park Company, was at the heart of the notable case of Foss v Harbottle in mid-19th century England.

While once very popular in France, Britain, and the United States, tontines have been banned in Britain, pursuant to the British Life Assurance Act 1774, 14 Geo. 3, c. 48, and as amended, and in the United States. See, e.g., Warnock v. Davis, 104 U.S. 775, 779 (1881).[13] Such financial instruments are illegal primarily because they create beneficiaries who have an interest in the reduced lifespan of another person, and because many of these schemes were little more than swindles that encourage mischief against the life of the insured. Geneva, in Switzerland, was known for its active market in tontines in the 17th and 18th centuries. The First Life Directive of the European Union specified tontines as a class of insurance business to be underwritten by authorised and regulated companies, but that part of the regulations was not enacted in the United Kingdom.

Projects

The proceeds of the subscription were often used to fund private or public works projects. These sometimes contained the word "tontine" in their name.

- The Tontine Hotel in Ironbridge, Shropshire, stands prominently at one end of the Iron Bridge from which the town takes its name: it was built in 1780–84 by the proprietors of the bridge to accommodate tourists who came to view this wonder of the industrial age.

- The Tontine Coffee House on Wall Street in New York City, built in 1792, was the first home of the New York Stock Exchange.

- The first Freemasons' Hall, London. Subscribers were able to nominate someone other than themselves as the person on whose life the share was staked. On the subscriber's death they could leave their share to that person, or to anyone else. The scheme raised £5,000, but cost £21,750 in interest over its 87-year life.[14]

Broader uses of the term

In French-speaking cultures, particularly in developing countries, the meaning of the term "tontine" has broadened to encompass a wider range of semi-formal group savings and microcredit schemes. The crucial difference between these and tontines in the traditional sense is that benefits do not depend on the deaths of other members.

In the U.K. during the mid-20th century, the term was applied to communal Christmas saving schemes, with participants making regular payments of an agreed sum through the year, which would be withdrawn shortly before Christmas to fund gifts and festivities.[15]

As a type of rotating savings and credit association (ROSCA), tontines are well established as a savings instrument in central Africa, and in this case function as savings clubs in which each member makes regular payments and is lent the kitty in turn. They are wound up after each cycle of loans.[16] In West Africa, "tontines" - often consisting of mainly women - are an example of economic, social and cultural solidarity.[17]

Informal group savings and loan associations are also traditional in many east Asian societies, and under the name of tontines are found in Cambodia, and among emigrant Cambodian communities.[18]

Tontine pensions

In 2015, John Barry Forman and Michael J. Sabin, using modern actuarial techniques to calculate fair transfer payments when participants are different ages and have made different contributions, proposed a new structure of pension plan on the tontine model, through which large employers could provide retirement income for their employees. They argued that tontine pensions would have two major advantages over traditional pensions, as they would always be fully funded, and the plan sponsor would not be required to bear the investment and actuarial risks.[19] Similar arguments were put forward in the same year by Moshe Milevsky.[20]

In popular culture

Tontines have been featured in:

- La Tontine (1708), a comic play by Alain-René Lesage. A physician hoping to raise the funds to give his daughter a dowry buys a tontine on the life of an elderly peasant, whom he then strives to keep alive.

- The Great Tontine (1881), a novel by Hawley Smart.

- The Wrong Box (1889), a comic novel by Robert Louis Stevenson and Lloyd Osbourne. The plot revolves around a tontine originally taken out for some wealthy English children, and the shenanigans resulting as younger family members of the two final survivors vie to secure the final payout. The book was adapted as a film (produced and directed by Bryan Forbes) in 1966.

- The Secret Tontine (1912), an atmospheric faux-gothic novel by Robert Murray Gilchrist, set in the Derbyshire Peak District during a snowy winter in the late 19th century. The plot involves the potential beneficiaries of a covert tontine scheming to murder their ignorant rivals.

- Lillian de la Torre's short story "The Tontine Curse" (1948) features mysterious deaths related to a tontine in 1779, being investigated by Samuel Johnson.

- The Tontine (1955), a novel by Thomas B. Costain, illustrated by Herbert Ryman. Set in nineteenth-century England, the story centres around the fictional "Waterloo" tontine, established to benefit veterans of the Napoleonic wars. Among other plot twists, shareholders hire an actor to impersonate a dead nominee, and conspire to murder another member.

- In 4.50 from Paddington (1957), a Miss Marple murder mystery by Agatha Christie, the plot revolves around the will of a wealthy industrialist, which establishes a settlement under which his estate is divided in trust among his grandchildren, the final survivor to inherit the whole. The settlement is described, inaccurately, as a tontine.

- Something Fishy (1957), a novel by P. G. Wodehouse, features a similar tontine, except it is the investors' sons that stand to gain from marrying late.

- In the U.S. television series The Wild Wild West, Episode 16 of Season Two (1966–67) – "The Night of the Tottering Tontine" – finds James West and Artemus Gordon protecting a man who is a member of a tontine whose members are being murdered one by one.

- "M*A*S*H" episode "Old Soldiers" (1980), 18th episode of 8th season, in which Col. Potter (Harry Morgan) is informed that he is the last surviving member of a tontine that consisted of several Army buddies from WWI. The tontine concerned a bottle of fine brandy from an abandoned château in which they had hidden together during an artillery barrage. As the episode ends, Potter and select members of the M*A*S*H unit (Benjamin "Hawkeye" Pierce, BJ Hunnicut, Margaret Houlihan, Father Francis Mulcahy, Max Klinger and Charles Emerson Winchester III) drink to a toast offered by Potter to his old WWI comrades and then a second one offered to the new friendships he has made with these comrades-in-arms in Korea.

- Barney Miller episode "The Tontine" (1982), in which one of the last two surviving family members who invested in the tontine attempted to kill himself, so that the other could have the money before growing too old to enjoy it.

- In The Simpsons episode "Raging Abe Simpson and His Grumbling Grandson in "The Curse of the Flying Hellfish"" (1996), Grandpa Simpson and Mr. Burns are the final survivors of a tontine to determine ownership of art looted during World War II.

- The 2001 comedy film Tomcats features a variation on a tontine where the last investor to get married gets the full amount of the invested funds.

- In the Archer episode "The Double Deuce" (2011), it is revealed that Archer's butler Woodhouse is one of three final survivors of a group of World War I Royal Flying Corps squadron mates who each put £50 into an interest-bearing account which is worth nearly a million dollars at present. The office workers at ISIS HQ, realizing that a new tontine could capitalize on the high mortality rate of field agents, began persuading people to join while remaining safely behind a desk.

- In The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014), directed by Wes Anderson, the Last Will and Testament of Madame Céline Villeneuve Desgoffe und Taxis "consists of a general tontine...in combination with 635 amendments, notations, corrections and letters of wishes."

References

- 1 2 "When Others Die, Tontine Investors Win". nytimes.com. 2017-03-24. Retrieved 2017-03-27.

- ↑ Jennings; Swanson; Trout (1988), p. 107

- 1 2

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Tontine". Encyclopædia Britannica. 27 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Tontine". Encyclopædia Britannica. 27 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. - 1 2 Milevsky 2015.

- ↑ Weir 1989, pp. 95–124

- 1 2 3 4 Weir 1989, pp. 103–104

- ↑ Description des Machines et Procédés Specifies Dans Les Brévets D’Invention, De Perfectionnement et D'Importation, 1811 pp 544 et seq.

- ↑ Coudy 1957

- ↑ Jennings and Trout 1982.

- 1 2 Weir 1989.

- ↑ Buley 1967, p. 291.

- ↑ Buley 1967, p. 472.

- ↑ The Insurable Interest Requirement for Life Insurance: Recent Developments

- ↑ "MQ Magazine, issue 19". United Grand Lodge of England.

- ↑ For a description and images of a contribution card, see http://rhostyllen.info/misc.html

- ↑ Henry, Alain (June 19, 2003). "Using tontines to run the economy" (PDF). l'École de Paris du management.

- ↑ Bruchhaus, Eva-Maria (November 3, 2016). "Flexible and disciplined". D+C, Development and Cooperation.

- ↑ Liev, Man Hau (November 26–29, 1997). "Tontine: an alternative financial instrument in Cambodian communities". 12th NZASIA Conference.

- ↑ Forman, John Barry; Sabin, Michael J. (2015). "Tontine Pensions" (PDF). University of Pennsylvania Law Review. 163 (3): 755–831.

- ↑ Milevsky 2015, pp. 170–97.

Sources

- Buley, R. Carlyle (1967). The Equitable Life Assurance Society of the United States 1859–1964. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

- Coudy, Julien (1957). "La Tontine royal sous le règne de Louis XIV". Revue historique de droit français et étranger. 4th ser. 35: 128–33. (in French)

- Dunkley, John (2007). "Bourbons on the Rocks: tontines and early public lotteries in France". Journal for Eighteenth-Century Studies. 30: 309–23. doi:10.1111/j.1754-0208.2007.tb00338.x.

- Gallais Hamonno, Georges; Berthon, Jean (2008). Les emprunts tontiniers de l'Ancien Régime: un exemple d'ingénierie financière au XVIIIe siècle. Paris. (in French)

- Jennings, Robert M.; Trout, Andrew P. (1976). "The Tontine: fact and fiction". Journal of European Economic History. 5: 663–70.

- Jennings, Robert M.; Trout, Andrew P. (1982). The Tontine: from the reign of Louis XIV to the French Revolutionary era. Homewood, IL.

- Jennings, Robert M.; Swanson, Donald F.; Trout, Andrew P. (1988). "Alexander Hamilton's Tontine Proposal". William and Mary Quarterly. 3rd ser. 45 (1): 107–115. JSTOR 1922216.

- McKeever, Kent (2011). "A Short History of Tontines". Fordham Journal of Corporate & Financial Law. 15 (2): 491–521.

- Milevsky, Moshe A. (2015). King William's Tontine: why the retirement annuity of the future should resurrect its past. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-110-707612-9.

- Weir, David R. (1989). "Tontines, Public Finance, and Revolution in France and England, 1688-1789". Journal of Economic History. 49: 95–124. doi:10.1017/s002205070000735x.

- Wyler, Julius (1916). Die Tontinen in Frankreich. Munich and Leipzig. (in German)

External links

| Look up tontine in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- "The Great Tontine Gamble", one of a series of articles by Burton J. Hendrick appearing in McClure's Magazine in 1906

- The Straight Dope: "What's with tontines, the odd annuities in which you benefit when others die?"

- Baker et al. (Winter 2009-2010) "Tontines for the Young Invincibles", Regulation