Tlaxcala City

| Tlaxcala Tlaxcala de Xicohténcatl | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Municipality | ||||||

Tlaxcala City | ||||||

| ||||||

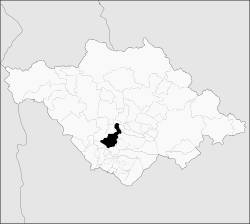

Location of Tlaxcala within Tlaxcala | ||||||

| Coordinates: 19°18′45″N 98°14′24″W / 19.31250°N 98.24000°WCoordinates: 19°18′45″N 98°14′24″W / 19.31250°N 98.24000°W | ||||||

| Country |

| |||||

| State |

| |||||

| Founded | October 3, 1525 | |||||

| Municipal Status | 1813 | |||||

| Government | ||||||

| • Municipal President | Anabell Ávalos Zempoalteca[1] | |||||

| Elevation (of seat) | 2,239 m (7,346 ft) | |||||

| Population (2010) Municipality | ||||||

| • Municipality | 89,795 | |||||

| Demonym(s) | Tlaxcaltecas | |||||

| Time zone | CST (UTC-6) | |||||

| Postal code (of seat) | 90000 | |||||

| Area code(s) | 246 | |||||

Tlaxcala, officially Tlaxcala de Xicohténcatl (Spanish ![]() [tla(k)sˈkala] , Nahuatl: Tlaxcallān Xīcohtēncatl [tɬaʃˈkalːaːn ʃiːkoʔˈteːŋkatɬ]), is the capital city of the Mexican state of Tlaxcala and seat of the municipality of the same name. The city did not exist during the pre Hispanic period but was laid out by the Spanish as a center of evangelization and governance after the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire. It was designated as a diocese but eventually lost this status to Puebla as its population declined. The city still has many of its old colonial structures including the former Franciscan monastery, as well as newer civic structures such as the Xicohténcatl Theater.

[tla(k)sˈkala] , Nahuatl: Tlaxcallān Xīcohtēncatl [tɬaʃˈkalːaːn ʃiːkoʔˈteːŋkatɬ]), is the capital city of the Mexican state of Tlaxcala and seat of the municipality of the same name. The city did not exist during the pre Hispanic period but was laid out by the Spanish as a center of evangelization and governance after the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire. It was designated as a diocese but eventually lost this status to Puebla as its population declined. The city still has many of its old colonial structures including the former Franciscan monastery, as well as newer civic structures such as the Xicohténcatl Theater.

The city

The city center is compact and filled with colonial era building painted in colors such as burnt umber, salmon pink and mustard yellow.[2] Most of these buildings are centered on the main square called the Plaza de la Constitución. This square measures 75 metres (246 feet) on each side and was established when the Spanish laid out the city in 1524. The current name was given in 1813 to honor the Cádiz Constitution as well as the Mexican constitutions of 1857 and 1917. In the center of this square is the Santa Cruz Fountain which was donated to the city by Philip IV in 1646. There is also a kiosk which was constructed in the 19th century.[3]

The Portal Hidalgo is on the east side of the main square, built as commercial space in 1550. It is still used as such today although the structures have been modified since then as seen in the differences in the columns and sizes of the arches. The city hall was moved from its centuries old home in the “Casas Reales” to this complex. The interior is dominated by the city council chamber (Salón de Cabildos) along with various municipal offices. On the lower level inside its section of the arches, there is a cultural space called “La Tlaxcalteca” which sells regional handcrafts and other goods as well as books about Tlaxcala’s history.[4]

Historic buildings

The Capilla Real de Indias or Royal Indian Chapel was built in the 16th century as a church for indigenous nobility. At the end of the 18th century, a fire destroyed the nave and much of the rest collapsed as a result of an earthquake. The ruins remained abandoned until the structure was restored in 1984 to house the state’s judicial branch.[3]

The Casa de Piedra ("Stone House") is located on the southwest corner of the main plaza. It was built in the 16th century as a notary office and home. Its name comes from the solid gray sandstone used in its construction, unique to the area.[3]

- Franciscan monastery

The former Franciscan monastery was built between 1537 and 1542, located on a hill on the edge of the historic center, away from the main square. It was one of the first four to be built by the Franciscans in the Americas, accredited to Martín de Valencia. The layout of the complex is unusual with the cloister on the left or north side of the church. The church still has its original roof made from large beams of wood.[5] The main nave of the church has one of the few examples of Moorish art in the Americas.[4] It has a large atrium and various chapels, with only two of the atrium chapels remaining. There is a tower located on the outside wall away from the main building.[5] The east atrium is historically important as the site of the first evangelist plays performed in Nahuatl starting in 1537. Today, this cloister area is the Regional Museum of Tlaxcala.[3] The main gateway to the monastery has the coat-of-arms of Castillas and the year 1629, mostly likely to mark the centennial of the monastery’s founding.[4] The after its use as a monastery ended, the cloister was used as a military barracks, a hospital and a prison. Only some of its original murals remain. It has been the home of the Regional Museum since 1981. The museum contains five halls dedicated to the history of the state from the pre-Hispanic period to the 19th century and it has two halls for temporary exhibits. The museum also hosts conferences and cultural events. Other services include those related to research. The museum is operated by the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia (INAH) .[5]

The Jorge Aguilar “El Ranchero” Bullring is on a site next to the former monastery. It was one of the first established in Tlaxcala in 1788. In 1817, the current structure was built of adobe and stone. The popularity of the sport spurred a number of ranches dedicated to raising bulls including the Tepeyahualco, Piedras Negras and Mimiahuapan. It is located next to the former monastery and also serves as the site for the annual Tlaxcala Fair.[3][4]

The State Government Palace is the most important civic construction from the 16th century. It has three sections. The east wing was known as the Casas Reales, the center Casas Consistoriales and the west wing as the Alhóndiga. The building is used for state government offices. The interior contain a number of murals by Desiderio Hernández Xochitiotzin, which depict the history of Tlaxcala.[3]

- San José parish church

The San José parish church was originally called the parish of San Juan y San José (Saints John and Joseph), constructed during the 18th century in Baroque style. This site was once the cathedral of the Diocese of Tlaxcala, but this has since been merged with Puebla, with its seat in the city of Puebla. The building has orange walls with cobalt blue Talavara ceramic tiles and a façade decorated in mortar work.[2][4] The main entrance is an arch supported by pilasters and flanked by columns. The upper part of the façade has a choral window also flanked by columns. The left hand tower has one level with arches, flanked by Tuscan pilasters topped by a small dome covered in Talavera tile. In 1864, the cupola and roof were destroyed by an earthquake. The current ones with Talavera tile are from the reconstruction. The interior is decorated in Neoclassical style with a Latin cross layout although there are still some Baroque and Churrigueresque altars. The main altar is Neoclassical but with an altarpiece which is Baroque. The upper choir area has an elaborate wood railing. On each side of the area below the choir area there are two Churrigueresque altars. In the two side chapels there are oil paintings by Manuel Caro as well as two holy water fonts of sculpted stone that has images of the god Camaxtli and the Spanish coat of arms.[4]

The former municipal palace was constructed in the middle of the 16th century as a place for the representatives of the four Tlaxcala dominions to meet. It has two levels with arches on the lower level of the façade. The main entranceway has three arches with reliefs over stone columns. The upper level of the façade has a seal and a pediment with clock. The interior has a terrace with three arches supported by Tuscan columns. The main stairway has a relief depicting Xicohténcatl Axayacatzin as well as reliefs of the four Tlaxcalan leaders at the time of the Spanish arrival.[4]

The Former Legislative Palace is now home to the state’s Secretary of Tourism. It was built in the 19th century with a façade of gray sandstone supported by pilasters with capitols. The building functioned as the site of the state’s legislature from 1901 to 1982.[3]

The Xicohténcatl Theater was built in 1873 with one of its early main productions being a re-enactment of the Battle of Puebla. Built during the Porfirio Díaz period, it was remodeled after the Mexican Revolution to Neoclassical from 1923 to 1945. The latest restoration of the building occurred in 1984 done by the Instituto Tlaxcalteca de Cultura. The Xicohténcatl. It has a sandstone façade, which is principally in Neoclassical style. This façade has twelve pilasters with Corinthian capitols that mark off the windows, doors and niches. The lower level has three entrances and the upper level has three balconies with arches. The interior has a ceiling with a large soffit with an Art Nouveau style painting by John Fulton representing the Muses along with Tlaxcala landscapes.[3][4]

The Tlaxcala Museum of Art was inaugurated in 2004, located in a building constructed in the 19th century in the historic center. This building originally was a hospital and later jail. When it was restored and converted to its current use, the façade and layout of the building was left intact with only minor changes. The museum has six main halls for permanent exhibits and five for temporary ones.[6]

The Culture Palace is a late Neoclassical building which was begun in 1939. It has a brick façade with a woven mat design interspersed with ornamental gray sandstone. It was originally built to be the middle and preparatory school for the state, but later it was converted into a department of the Universidad Autónoma de Tlaxcala and finally in 1991, housed the Tlaxcala Cultural Institute.[3]

The Stairway of the Heroes was initially called the “Stairway of Independence” both of which refer to the busts of figures such as Miguel Hidalgo, Ignacio Allende, José María Morelos and Josefa Ortiz de Domínguez. Busts from persons later in Mexico’s history were added such as those of Francisco I. Madero, Ricardo Flores Magón, Emiliano Zapata, Francisco Villa, Venustiano Carranza as well as Domingo Arenas, who was a Tlaxcalan figure from the Mexican Revolution.[3]

Plaza Xicohténcatl was created in the late 20th century for a weekend arts and crafts market. In the colonial period, the area was used for the sale of slaves according to some historians. Calzada de San Francisco is a pedestrian street at the southeast side of the plaza, filled with ash trees and paved with blocks of sandstone. As the road leads up to the former monastery, it ends at a gate with three arches.[3]

La Chichita is the name of a fountain found at the intersection of Vicente Guerrero and Porfirio Díaz streets. It is fed by a natural water flow and used to be the source of potable water for the surrounding area.[3]

- Tizatlán Open Chapel

The Tizatlán Open Chapel was built in the 16th century over a pyramid platform which was part of the palace of Xicohténcatl the Elder. This building appears in the Tlaxcala Codex from 1550. Hernán Cortés placed a cross here along with indigenous leaders Maxixcatzin and Xicohténcatl. There are still fragments of murals depicting the baptism of Jesus, the Three Wise Men and of God, the Father, surrounded by angels playing musical instruments. Adjoining this is the Tizatlán archeological site, in which still remain six semicircular columns, two altars with paintings similar to those of the Borgia Codex, where the gods Tezcatlipoca and Tlahuizcalpantecutli appear.[4]

The Chapel of the Well of the Miraculous Water (Capilla del Pocito de Agua Milagrosa) is a small building at a fresh water spring. It began as a wall built to protect the spring at the end of the 17th or beginning of the 18th century. The chapel building dates from between 1892 and 1896 but the entrance arch is older. It has an octagonal layout. One of the walls contains an oil by Isauro G. Cervantes from 1913 and the rest of the walls have murals with Biblical scenes related to water done by Desiderio Hernández Xochitiotzin and Pedro Avelino. Traditionally, red pottery ducks are sold in the small atrium as object of devotion or for healing.[4]

The Chapel of San Nicolasito was originally constructed of wood in the 16th century dedicated to Nicholas of Tolentino. In the 19th century the chapel was reconstructed to what is now one of the side chapels. Little by little it was enlarged to its present size.[4]

The San Esteban Temple was constructed from sandstone in the 20th century in Neoclassical style. Its atrium serves as a cemetery and its interior has a mural depicting the baptism of the four indigenous lords of Tlaxcala in the 16th century.[4]

The San Buenaventura Atempan hermitage was constructed around the time that Cortés was building the brigantines to invade Tenochtitlan. At that time, the structure was in a very rural area. Over the centuries it was abandoned and crumbled with only some of the walls remaining. Some of its images and other objects can now be found at a new temple nearby.[4]

Events

The city celebrates Carnival starting the Friday before Ash Wednesday, with the burning of an effigy to represent “bad humor” accompanied by funeral music. The following day, the queen of the carnival is selected. The main parade with floats occurs on Tuesday. During the long weekend there are various other events such as dance contests and recitals of traditional dace such as that of the Huehues from the community of Acuitlapilco. On Ash Wednesday, ceremonies end with a hanging of an effigy called “La Octava del Carnaval” Often the image is satirical, and of a person considered worthy of criticism.[4]

The Feria de Todos Santos is an important event, dedicated to the agriculture, handcrafts and industry of the state. It also has cultural events such as concerts, art exhibits and dance as well as regional food and an inaugural parade.[4]

The municipality

The city is the governing authority for itself and fifteen other communities, forming a territory of 41.61 square kilometres (16.07 square miles).[4][7] It is located in the south of the state, where most of the population is concentrated. It borders the municipalities of Totolac, Apetatitlán de Antonio Carvajal, Tepeyanco, Tetlatlahuca, San Damián Texoloc, San Jerónimo Zacualpan, Chiautempan, La Magdalena Tlaltelulco, San Isabel Xiloxoxtla and Panotla The municipal government consists of a municipal president, an officer called a “síndico” and seven representatives called “regidors.”[4]

The municipality has a very low level of socioeconomic marginalization, with no community having a state of medium and high marginalization. There are 23,035 residences as of 2010.[7]

Significant communities outside the municipal seat include Ocotlán, San Estebán Tizatlán, San Gabriel Cuauhtla, San Hipólito Chimalpa, San Lucas Cuauhtelupan and Santa Maria Acuitlapilco.[7] The Sanctuary of Our Lady of Ocotlán was consecrated in 1854 and in 1905 it was declared the parish church of Ocotlán. In 1907, it was declared a collegiate church and in 1957, it became a minor basilica. The church is in Tlaxcalan Baroque style characterized by the use of tile and red brick. The façade is built to look like an altarpiece and topped with a seashell image. The main entrance is an arch flanked by estipite and Salomonic columns with have images of the doctors of the church, as well as the twelve Apostles. Saint Joseph appears in the arch. Above this is a figure representing the Immaculate Conception and Francis of Assisi. Near this is the choral window in the form of a stylized star. The towers were construction in the latter 18th century with arches and vegetative decoration. The cupola contains four mirrors with the cornice covered in gold leaf. The ante-sacristy has five oil paintings by Manuel Caro done in 1781 depicting scenes of some of the Virgin Mary’s appearances. The sacristy has a painting of Saint Joseph by Joaquin Magón from 1754. The Guadalupe chapel to the side has lead figures of the Four Evangelists as well as paintings by Miguel Lucas Bedolla and Manuel Yañez. The image of the virgin is in a Baroque chamber decorated in plasterwork by Francisco Miguel Tlayoltehuanitzin between 1715 and 1740 and eight Salomonic columns.[4]

Geography and environment

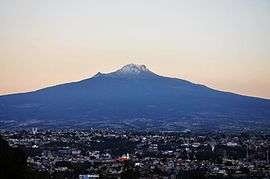

The city is located in the central Mexican highlands 2,239 metres (7,346 feet) above sea level, in a valley of the same name, from which the Popocatépetl and Iztaccíhuatl volcanoes can be seen in the distance.[2][4] The main elevations in the municipality are El Cerro Ostol at 2,460 metres (8,070 feet) and El Cerro Tepepan at 2,320 metres (7,610 feet).[4]

The main river in the municipality is the Zahuapan, which is part of the Balsas River region and the basin of the Atoyac River. Other rivers include the Huizcalotla, Negros, Tlacuetla and Lixcatlat. There are remnants of the former lake of Acuitlapilco as well. Other sources of fresh water include a spring in Acuitlapilco and a stream in Tepehitec which runs during the rainy season.[4]

The climate is temperate and semi-moist with most rain in the summer. The average annual high temperatures is 24.3 °C (75.7 °F) and the average low is 7.2 °C (45.0 °F).[4]

The higher elevations of the municipality have forests of pine, holm oak and white cedar. The mid range elevations are mostly secondary vegetation dominated by bush and low growing trees. The flat areas are dominated by a number of dry tolerate plants such as agave, nopal cactus and grasses. Because of the expansion of the urban area, the municipally only has small mammals such as rabbits, squirrels and opossums, along with some species of birds and reptiles as wildlife.[4]

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Record high °C (°F) | 28.4 (83.1) |

31.0 (87.8) |

35.0 (95) |

34.0 (93.2) |

39.2 (102.6) |

34.0 (93.2) |

30.0 (86) |

31.0 (87.8) |

31.0 (87.8) |

36.5 (97.7) |

29.2 (84.6) |

30.0 (86) |

39.2 (102.6) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 22.1 (71.8) |

23.5 (74.3) |

25.9 (78.6) |

27.3 (81.1) |

27.5 (81.5) |

25.4 (77.7) |

24.5 (76.1) |

24.7 (76.5) |

23.9 (75) |

24.3 (75.7) |

23.5 (74.3) |

22.3 (72.1) |

24.6 (76.3) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 12.5 (54.5) |

13.6 (56.5) |

15.8 (60.4) |

17.7 (63.9) |

18.6 (65.5) |

18.2 (64.8) |

17.3 (63.1) |

17.5 (63.5) |

17.3 (63.1) |

16.5 (61.7) |

14.5 (58.1) |

13.0 (55.4) |

16.0 (60.8) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 2.9 (37.2) |

3.7 (38.7) |

5.8 (42.4) |

8.0 (46.4) |

9.8 (49.6) |

11.1 (52) |

10.2 (50.4) |

10.3 (50.5) |

10.6 (51.1) |

8.7 (47.7) |

5.4 (41.7) |

3.6 (38.5) |

7.5 (45.5) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −5.0 (23) |

−4.0 (24.8) |

−1.9 (28.6) |

0.0 (32) |

2.5 (36.5) |

3.0 (37.4) |

4.0 (39.2) |

2.4 (36.3) |

−0.5 (31.1) |

−0.3 (31.5) |

−4.5 (23.9) |

−7.4 (18.7) |

−7.4 (18.7) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 8.7 (0.343) |

7.4 (0.291) |

10.4 (0.409) |

31.1 (1.224) |

74.8 (2.945) |

158.1 (6.224) |

156.4 (6.157) |

162.2 (6.386) |

140.0 (5.512) |

68.0 (2.677) |

11.1 (0.437) |

6.3 (0.248) |

834.5 (32.854) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 1.4 | 1.5 | 2.5 | 6.6 | 12.2 | 17.4 | 19.0 | 19.0 | 16.8 | 9.0 | 2.5 | 1.2 | 109.1 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 70 | 67 | 66 | 67 | 69 | 75 | 77 | 77 | 79 | 74 | 70 | 73 | 72 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 218 | 220 | 251 | 218 | 196 | 154 | 167 | 174 | 176 | 221 | 226 | 216 | 2,437 |

| Source #1: Servicio Meteorológico National (humidity 1981–2000)[8][9] | |||||||||||||

| Source #2: Deutscher Wetterdienst (sun, 1961–1990)[10][lower-alpha 1] | |||||||||||||

History

The name Tlaxcala most likely comes from a Nahuatl phrase which means “place of tortillas.” The Aztec glyph for the Mesoamerican dominion is two hills from which emerge a pair of hands making a tortilla.[4]

The site of the modern city did not have a settlement for most of the pre Hispanic era. The area was ruled by a coalition of four dominions called Tepeticpac, Ocotelolco, Tizatlan and Quiahuiztlan which united in the 14th century to defend themselves against the Aztecs and other enemies. In the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, Tlaxcala was one of the most important areas of Mesoamerica with commercial ties to the Gulf of Mexico to the Pacific Ocean as well as Central America.[4]

As the Aztec Empire grew, it conquered Tlaxcala’s neighbors but left the dominion in order to perform annual ritual combat called the “flower wars” which aimed to not conquer but capture soldiers for sacrifice. The conquest of the surrounding area also cut off Tlaxcala’s commerce. This remained the case until the arrival of the Spanish in the early 16th century. Hernán Cortés took advantage of this situation, enlisting the Tlaxcalans as allies against the Aztecs, given them a base to attack from and regroup after the La Noche Triste when they were initially expelled from Tenochtitlan.[4]

Despite the military alliance of the Tlaxcalans, they did not have a single capital. After the Spanish conquest terminated, the Europeans selected the current site to solidify their hold on the Tlaxcalans as well as have a base for evangelization. The most likely time that the city was founded was spring of 1522.[4] Tlaxcala was the fifth diocese to be established in the Americas and the second in Mexico after Yucatán. The first bishop was Julian Garces and the seat was established in 1527. However, since there was a cathedral in the city of Puebla and not in Tlaxcala, the seat was moved to Puebla in 1539 and has remained there since. The original territory of the diocese included the states of Puebla, Tlaxcala, Veracruz, Tabasco, Hidalgo and Guerrero, but as new diocese were erected, the territory reduced to the present, states of Puebla and Tlaxcala. In 1903, the name of the Diocese of Tlaxcala was changed to the Diocese of Puebla.[11]

At the time of the Spanish conquest, the Tlaxcala area was heavily populated but with epidemics, emigrations and the construction of the Nochistongo canal to drain the Valley of Mexico, most of the indigenous population disappeared. A document of 1625 states that there were 300,000 in the city in the 16th century but only 700 remained by that time it was written.[11] The city was begun in 1537 with the construction of the San Francisco monastery. The city became the center of Tlaxcala identity during the colonial period. Its commerce was originally centered in the main square but was eventually moved to the outskirts of town. One important project that was traded here was the cochineal insect, used to make red dye. When New Spain was divided into five major provinces, Tlaxcala became the capital of one of them, with roughly the same dimensions as the pre Hispanic coalition of dominions. Tlaxcala was promised certain rights as an ally during the Conquest. When a number of these were not met, a codex was produced here called the Lienzo de Tlaxcala as a complaint to the Spanish Crown. However, despite the complaints, most of the indigenous eventually lost their lands around the city and lost many of their commerce rights in it.[4]

In 1692, a revolt occurred against Governor Manuel de Bustamante y Bustillo due to the scarcity of grain.[4]

The city of Tlaxcala became a municipality in 1813, under the Spanish Constitution of 1812.[4]

French forces were forced out of the city in 1867 after which Tlaxcalan forces went with Porfirio Díaz to liberate Puebla and after that, Querétaro and Mexico City.[4]

During the end of the 19th century, the politics of the city were dominated by Próspero Cahuantzi, who promoted public works such as kiosks, streets, public markets, bridges and government buildings. The city changed from oil lamps to electric light in the historic center, the state government palace was remodeled and the Xicohténcatl Theater was built. Electricity for the city was generated through a hydroelectric works in a canal on the Los Negros River.[4]

After the Mexican Revolution, the city recovered and began to grow again, reaching a population of 6,000 by 1927. In the mid 20th century, public education was enhanced at the middle and high school levels. More public works were undertaken to give the city the appearance it has today.[4]

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ciudad de Tlaxcala. |

- ↑ Tlalmis, Leonel (2 January 2017). "Ofrece Anabell Ávalos Zempoalteca transformar la capital" (in Spanish). El Sol de Tlaxcala. Retrieved 4 January 2017.

- 1 2 3 Freda Moon (November 23, 2011). "An Old-World Escape Near Mexico City". New York Times. Retrieved March 11, 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 "Tlaxcala" (in Spanish). Mexico: Secretaría de Turismo de Tlaxcala. 2011. Retrieved March 11, 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 "Tlaxcala". Encyclopedia de los Municipios y Delegaciones de México – Estado de Tlaxcala (in Spanish). Mexico: INAFED Instituto para el Federalismo y el Desarrollo Municipal and SEGOB Secretaría de Gobernación. 2010. Retrieved March 11, 2012.

- 1 2 3 "El Museo Regional de Tlaxcala cumple 30 años difundiendo cultura" [The Tlaxcala Regional Museum completes thirty years of diffusing culture] (Press release) (in Spanish). INAH. March 25, 2011. Retrieved March 11, 2012.

- ↑ "Museo de Arte de Tlaxcala (MAT)". Sistema de Información Cultural (in Spanish). Mexico: CONACULTA. Retrieved March 11, 2012.

- 1 2 3 "Resumen municipal Tlaxcala" [Municipal summary Tlaxcala] (in Spanish). Mexico: SEDESOL. Retrieved March 11, 2012.

- ↑ "Estado de Tlaxcala–Estacion: Tlaxcala de Xicontecatl (DGE)". NORMALES CLIMATOLÓGICAS 1951–2010 (in Spanish). Servicio Meteorológico National. Retrieved 7 May 2015.

- ↑ "NORMALES CLIMATOLÓGICAS 1981–2000" (PDF) (in Spanish). Servicio Meteorológico Nacional. Retrieved 7 May 2015.

- ↑ "Station 76683 Tlaxcala, TLAX.". Global station data 1961–1990—Sunshine Duration. Deutscher Wetterdienst. Retrieved 7 May 2015.

- 1 2 "Tlaxcala". New Advent Catholic Encyclopedia. Retrieved March 11, 2012.

Notes

- ↑ Station ID for Tlaxcala, TLAX is 76683 Use this station ID to locate the sunshine duration

Further reading

- Antonio de Solís; Thomas Townsend (1738). "Description of the City of Tlascala". History of the Conquest of Mexico by the Spaniards. London.