County Tipperary

| County Tipperary Contae Thiobraid Árann | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

| ||

| Country | Ireland | |

| Province | Munster | |

| County towns | Nenagh / Clonmel / Thurles | |

| Dáil Éireann | Tipperary | |

| EU Parliament | South | |

| Government | ||

| • Type | County Council | |

| Area | ||

| • Total | 4,305 km2 (1,662 sq mi) | |

| Area rank | 6th | |

| Population (2016) | 160,441 | |

| • Rank | 12th | |

| Vehicle index mark code | T | |

| Website |

www | |

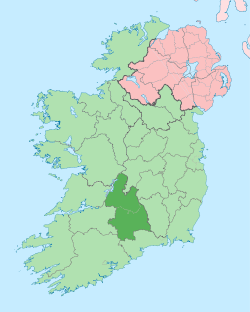

County Tipperary (Irish: Contae Thiobraid Árann) is a county in Ireland. Tipperary County Council is the local government authority for the county. Between 1898 and 2014 county Tipperary was divided into two counties, North Tipperary and South Tipperary, which were unified under the Local Government Reform Act 2014, which came into effect following the 2014 local elections on 3 June 2014.[1] It is located in the province of Munster. The county is named after the town of Tipperary, and was established in the early thirteenth century, shortly after the Norman invasion of Ireland. The population of the entire county was 160,441 at the 2016 census.[2] The largest towns are Clonmel, Nenagh and Thurles.

Geography and political subdivisions

Tipperary is the sixth largest of the 32 counties by area and the 12th largest by population.[3] It is the third largest of Munster's 6 counties by size and the third largest by population. It is also the largest landlocked county in Ireland. The region is part of the central plain of Ireland, but the diverse terrain contains several mountain ranges: the Knockmealdown, the Galtee, the Arra Hills and the Silvermine Mountains. Most of the county is drained by the River Suir; the north-western part by tributaries of the River Shannon; the eastern part by the River Nore; the south-western corner by the Munster Blackwater. No part of the county touches the coast. The centre is known as 'the Golden Vale', a rich pastoral stretch of land in the Suir basin which extends into counties Limerick and Cork.

Baronies

There are 12 historic baronies in County Tipperary: Clanwilliam, Eliogarty, Iffa and Offa East, Iffa and Offa West, Ikerrin, Kilnamanagh Lower, Kilnamanagh Upper, Middle Third, Ormond Lower, Ormond Upper, Owney and Arra and Slievardagh.

Civil parishes and townlands

Parishes were delineated after the Down Survey as an intermediate subdivision, with multiple townlands per parish and multiple parishes per barony. The civil parishes had some use in local taxation and were included on the nineteenth century maps of the Ordnance Survey of Ireland.[4] For poor law purposes, District Electoral Divisions replaced the civil parishes in the mid-nineteenth century. There are 199 civil parishes in the county.[5] Townlands are the smallest officially defined geographical divisions in Ireland; there are 3,159 townlands in the county.[6]

Towns and villages

| Historical population | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

| 1600 | 23,454 | — |

| 1610 | 25,667 | +9.4% |

| 1653 | 31,597 | +23.1% |

| 1659 | 26,684 | −15.5% |

| 1821 | 346,896 | +1200.0% |

| 1831 | 402,563 | +16.0% |

| 1841 | 435,553 | +8.2% |

| 1851 | 331,567 | −23.9% |

| 1861 | 249,106 | −24.9% |

| 1871 | 216,713 | −13.0% |

| 1881 | 199,612 | −7.9% |

| 1891 | 173,188 | −13.2% |

| 1901 | 160,232 | −7.5% |

| 1911 | 152,433 | −4.9% |

| 1926 | 141,015 | −7.5% |

| 1936 | 137,835 | −2.3% |

| 1946 | 136,014 | −1.3% |

| 1951 | 133,313 | −2.0% |

| 1956 | 129,415 | −2.9% |

| 1961 | 123,822 | −4.3% |

| 1966 | 122,812 | −0.8% |

| 1971 | 123,565 | +0.6% |

| 1979 | 133,741 | +8.2% |

| 1981 | 135,261 | +1.1% |

| 1986 | 136,619 | +1.0% |

| 1991 | 132,772 | −2.8% |

| 1996 | 133,535 | +0.6% |

| 2002 | 140,131 | +4.9% |

| 2006 | 149,244 | +6.5% |

| 2011 | 158,754 | +6.4% |

| 2016 | 160,441 | +1.1% |

| [7][8][9][10][11][12] | ||

- Ahenny – Áth Eine

- Ardfinnan – Ard Fhíonáin

- Ballina – Béal an Átha

- Ballingarry – Baile an Gharraí

- Ballyclerahan – Baile Uí Chléireacháin

- Ballylooby – Béal Átha Lúbaigh

- Ballyporeen – Béal Átha Póirín

- Bansha – An Bháinseach

- Birdhill – Cnocán an Éin Fhinn

- Borrisokane – Buiríos Uí Chéin

- Borrisoleigh – Buiríos Ó Luigheach

- Cahir – An Chathair / Cathair Dún Iascaigh

- Cappawhite – An Cheapach na Bhfaoiteach

- Carrick-on-Suir – Carraig na Siúire

- Cashel – Caiseal

- Castleiney – Caisleán Aoibhne

- Clogheen – Chloichín an Mhargaid

- Cloneen

- Clonmel – Cluain Meala

- Clonmore – An Cluain Mhór

- Clonoulty – Cluain Ultaigh

- Cloughjordan – Cloch Shiurdáin

- Coalbrook – Glaise na Ghuail

- Cullen – Cuilleann

- Donohill – Dún Eochaille

- Drangan – Dun Drongan

- Drom – Drom

- Dromineer – Drom Inbhir

- Dualla – Dubhaille

- Dundrum – Dún Droma

- Emly – Imleach Iubhair

- Fethard – Fiodh Ard

- Golden – An Gabhailín

- Gortnahoe – Gort na hUamha

- Grangemockler – Grainseach Mhocleir

- Hollyford – Áth an Chuillinn

- Holycross – Mainistir na Croiche

- Horse and Jockey – An Marcach

- Killenaule – Cill Náile

- Kilmoyler – Cill Mhaoileachair

- Kilsheelan – Cill Siolain

- Knockgraffon – Cnoc Rafann

- Lisronagh – Lios Ruanach

- Littleton – An Baile Beag

- Lorrha – Lothra

- Loughmore – Luach Magh

- Milestone – Cloch an Mhíle

- Nenagh – An tAonach

- New Birmingham – Gleann an Ghuail

- New Inn – Loch Cheann

- Newport – An Tulach Sheasta

- Ninemilehouse – Tigh na Naoi Míle

- Rearcross – Crois na Rae

- Roscrea – Ros Cré

- Rosegreen – Faiche Ró

- Rathcabbin – An Rath Cabbàn

- Templemore – An Teampall Mór

- Thurles – Durlas

- Tipperary – Tiobraid Árann

- Toomevara – Tuaim Uí Mheára

- Two-Mile Borris – Buiríos Léith

- Upperchurch – An Teampall Uachtarach

- Silvermines- Beal Atha Gabhann

History

Following the Norman invasion of Ireland, the Kingdom of Munster was claimed as a lordship. By 1210, the sheriffdom of Munster shired into the shires of Tipperary and Limerick.[13] In 1328, Tipperary was granted to the Earls of Ormond as a county palatine or liberty.[13] The grant excluded church lands such as the archiepiscopal see of Cashel, which formed the separate county of Cross Tipperary.[13] Though the Earls gained jurisdiction over the church lands in 1662, "Tipperary and Cross Tipperary" were not definitively united until the County Palatine of Tipperary Act 1715, when the 2nd Duke of Ormond was attainted for supporting the Jacobite rising of 1715.[14][15]

The county was divided once again in 1838.[16] The county town of Clonmel, where the grand jury held its twice-yearly assizes, is at the southern limit of the county, and roads leading north were poor, making the journey inconvenient for jurors resident there.[16] A petition to move the county town to a more central location was opposed by the MP for Clonmel, so instead the county was split into two "ridings"; the grand jury of the South Riding continued to meet in Clonmel, while that of the North Riding met in Nenagh.[16] When the Local Government (Ireland) Act 1898 established county councils to replace the grand jury for civil functions, the ridings became separate "administrative counties" with separate county councils.[16] Their names were changed from "Tipperary North/South Riding" to "North/South Tipperary" by the Local Government Act 2001, which redesignated all "administrative counties" as simply "counties".[17] The Local Government Reform Act 2014 has amalgamated the two counties and restored a single county of Tipperary.[18]

Local government and politics

Following the Local Government Reform Act 2014, Tipperary County Council is the local government authority for the county. The authority is a merger of two separate authorities North Tipperary County Council and South Tipperary County Council which operated up until June 2014. The local authority is responsible for certain local services such as sanitation, planning and development, libraries, the collection of motor taxation, local roads and social housing. The county is part of the South constituency for the purposes of European elections. For elections to Dáil Éireann, the county is part of two constituencies: Tipperary North and Tipperary South. Together they return six deputies (TDs) to the Dáil.

Culture

Tipperary is referred to as the "Premier County", a description attributed to Thomas Davis, Editor of The Nation newspaper in the 1840s as a tribute to the nationalistic feeling in Tipperary and said that "where Tipperary leads, Ireland follows". Tipperary was the subject of the famous song "It's a Long Way to Tipperary" written by Jack Judge, whose grandparents came from the county. It was popular with regiments of the British army during World War I. The song "Slievenamon", which is traditionally associated with the county, was written by Charles Kickham from Mullinahone, and is commonly sung at sporting fixtures involving the county.[19]

Irish language

There are 979 Irish speakers in County Tipperary attending the five Gaelscoileanna (Irish language primary schools) and two Gaelcholáistí (Irish language secondary schools).[20]

Economy

The area around Clonmel is the economic hub of the county: to the east of the town the manufacturers Bulmers (brewers) and Merck & Co. (pharmaceuticals). There is much fertile land, especially in the region known as the Golden Vale, one of the richest agricultural areas in Ireland. Dairy farming and cattle raising are the principal occupations. Other industries are slate quarrying and the manufacture of meal and flour.

Tipperary is famous for its horse breeding industry and is the home of Coolmore Stud, the largest thoroughbred breeding operation in the world.

Tourism plays a significant role in County Tipperary – Lough Derg, Thurles, Rock of Cashel, Ormonde Castle, Ahenny High Crosses, Cahir Castle, Bru Boru Heritage Centre and Tipperary Crystal are some of the primary tourist destinations in the county.

Transport

Road transport dominates in County Tipperary. The M7 motorway crosses the north of the county through Roscrea and Nenagh and the M8 motorway bisects the county from north of Two-Mile Borris to the County Limerick border. Both routes are among some of the busiest roads on the island. The Limerick to Waterford N24 crosses the southern half of Tipperary, travelling through Tipperary Town, Bansha, north of Cahir and around Clonmel and Carrick-on-Suir.

Railways

Tipperary also has a number of railway stations situated on the Dublin-Cork line, Dublin-to-Limerick and Limerick-Waterford line. The railway lines connect places in Tipperary with Cork, Dublin Heuston, Waterford, Limerick, Mallow and Galway.

Sports

County Tipperary has a strong association with the Gaelic Athletic Association which was founded in Thurles in 1884. The Gaelic Games of Hurling, Gaelic football, Camogie and Handball are organised by the Tipperary GAA County Board of the GAA. The organisation competes in the All-Ireland Senior Hurling Championship and the All-Ireland Senior Football Championship. Tipperary, with 26 wins, are the only county to have won an all-Ireland title in every decade since the 1880s.

Horse racing takes place at Tipperary Racecourse, Thurles Racecourse and Clonmel Racecourse.

Places of interest

- Athassel Priory

- Cahir Castle

- Coolmore Stud

- Devil's Bit – a mountain near Templemore

- Dromineer

- Galtymore – a munro, and the highest mountain in County Tipperary (919m).

- Glen of Aherlow

- Glengarra Wood

- Holy Cross Abbey

- Kilcash Castle

- Lorrha

- Lough Derg

- Mitchelstown Cave

- Ormonde Castle, Carrick-on-Suir

- Redwood Castle (Castle Egan)

- Rock of Cashel

- Slievenamon – mountain associated with many Irish legends (721m)

Notable people

- Anne Anderson, ambassador to the United States

- John Desmond Bernal, controversial twentieth-century scientist

- Dan Breen, Irish Republican during the Irish War of Independence, later a TD for the county.

- William Butler, nineteenth-century army officer, writer, and adventurer

- Peter Campbell, founder of the Uruguayan navy

- The Clancy Brothers, folk music group

- Paddy Clancy, singer, harmonicist

- Tom Clancy, singer, actor

- Bobby Clancy, singer, banjoist

- Liam Clancy, singer, guitarist

- Kerry Condon, actress

- Frank Corcoran, composer

- Dayl Cronin, singer, member of boyband Hometown

- John N. Dempsey, Governor of Connecticut (1961–71)

- Dennis Dewane, American politician

- John M. Feehan, author and publisher

- Frank Fitzgerald, American politician

- Una Healy, singer, member of the girl group The Saturdays

- Patrick Hobbins, American politician

- Tom Kiely, Olympic gold medalist

- Shane MacGowan*, musician, songwriter, member of The Pogues

- Martin O'Meara, recipient of the Victoria Cross

- Frank Patterson, tenor

- Ramsay Weston Phipps, military historian

- Rozanna Purcell, model, winner of Miss Universe Ireland 2010.

- Adi Roche, Campaigner for peace, humanitarian aid and education, founder and chief executive of Chernobyl Children International

- Richard Lalor Sheil, politician, writer, and orator

- Pat Shortt, actor, comedian, and entertainer

- Laurence Sterne, author and clergyman, most famous for Tristram Shandy

- Denis Lynch, showjumper

- Lena Rice, Wimbledon Tennis Champion

- Seán Treacy, Irish Republican during the Irish War of Independence

See also

- Annals of Inisfallen

- High Sheriff of Tipperary

- List of civil parishes of County Tipperary

- List of abbeys and priories in the Republic of Ireland (County Tipperary)

- List of National Monuments in South Tipperary

- Lord Lieutenant of Tipperary

- Tipperary Hill, a neighbourhood in Syracuse, New York, United States, inhabited by many descendants of County Tipperary.

- Vehicle registration plates of Ireland

References

- ↑ "Tipperary County Council". Tipperary County Council. 29 May 2014.

Tipperary County Council will become an official unified authority on Tuesday, 3rd June 2014. The new authority combines the existing administration of North Tipperary County Council and South Tipperary County Council.

- ↑ Census 2016.

- ↑ Corry, Eoghan (2005). The GAA Book of Lists. Hodder Headline Ireland. pp. 186–91.

- ↑ "Interactive map (civil parish boundaries viewable in Historic layer)". Mapviewer. Ordnance Survey of Ireland. Retrieved 9 March 2010.

- ↑ "Placenames Database of Ireland – Tipperary civil parishes". Logainm.ie. 2010-12-13. Retrieved 2012-09-14.

- ↑ "Placenames Database of Ireland – Tipperary townlands". Logainm.ie. 2010-12-13. Retrieved 2012-09-14.

- ↑ For 1653 and 1659 figures from Civil Survey Census of those years, Paper of Mr Hardinge to Royal Irish Academy 14 March 1865.

- ↑ "Census for post 1821 figures.". Cso.ie. Retrieved 2012-09-14.

- ↑ histpop.org

- ↑ "NISRA – Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency". Nisranew.nisra.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 17 February 2012. Retrieved 2012-09-14.

- ↑ Lee, JJ (1981). "On the accuracy of the Pre-famine Irish censuses". In Goldstrom, J. M.; Clarkson, L. A. Irish Population, Economy, and Society: Essays in Honour of the Late K. H. Connell. Oxford, England: Clarendon Press.

- ↑ Mokyr, Joel; O Grada, Cormac (November 1984). "New Developments in Irish Population History, 1700-1850". The Economic History Review. 37 (4): 473–88. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0289.1984.tb00344.x.

- 1 2 3 Falkiner, Caesar Litton (1904). "The Counties of Ireland". Illustrations of Irish history and topography: mainly of the seventeenth century. Longmans, Green. pp. 108–42. Retrieved 14 August 2011.

- ↑ Deputy keeper of the public records in Ireland (1873-04-26). "Appendix 3: Extract from Report of the Assistant Deputy Keeper on the Records of the Court of Record of the County Palatine of Tipperary". Fifth Report. Command papers. C.760. HMSO. pp. 32–37. Retrieved 2011-08-14.

- ↑ Ireland (1794). "2 George I c.8". Statutes Passed in the Parliaments Held in Ireland. III: 1715–1733. Printed by George Grierson, printer to the King's Most Excellent Majesty. pp. 5–11. Retrieved 14 August 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 Murphy, Donal A. (1994). The two Tipperarys: the national and local politics, devolution and self-determination, of the unique 1838 division into two ridings, and the aftermath. Relay. ISBN 9780946327133.

- ↑ "Local Government Act, 2001 sec.10(4)(a)". Irish Statute Book. Retrieved 22 October 2013.

- ↑ Minister for Environment, Community and Local Government (15 October 2013). "sec.10(2) Boundaries of amalgamated local government areas". Local Government Bill 2013 (As initiated) (PDF). Dublin: Stationery Office. ISBN 978-1-4468-0502-2. Retrieved 17 October 2013.

- ↑ "Sliabh na mban – Slievenamon". Irishpage.com. Retrieved 2012-09-14.

- ↑ "Oideachas Trí Mheán na Gaeilge in Éirinn sa Ghalltacht 2010-2011" (PDF) (in Irish). gaelscoileanna.ie. 2011. Retrieved 9 January 2012.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to County Tipperary. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for County Tipperary. |

- Tipperary Institute

- County Tipperary Historical Society

- A website dedicated to the genealogical records of the county. It offers fragments of the 1766 census, the complete Down Survey, as well as a ream of other useful information

- Score for 'Quality of Life' in County Tipperary

- Gaelscoil stats

- Tipperary Studies

| Adjacent places of County Tipperary | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

County Galway |

County Offaly |

| |

| County Clare County Limerick |

|

County Laois County Kilkenny | ||

| ||||

| | ||||

| County Cork |

County Waterford | |||

Coordinates: 52°40′N 7°50′W / 52.667°N 7.833°W