Timeline of oviraptorosaur research

This timeline of oviraptorosaur research is a chronological listing of events in the history of paleontology focused on the oviraptorosaurs, a group of beaked, bird-like theropod dinosaurs. The early history of oviraptorosaur paleontology is characterized by taxonomic confusion due to the unusual characteristics of these dinosaurs. When initially described in 1924 Oviraptor itself was thought to be a member of the Ornithomimidae, popularly known as the "ostrich" dinosaurs, because both taxa share toothless beaks.[1] Early caenagnathid oviraptorosaur discoveries like Caenagnathus itself were also incorrectly classified at the time, having been misidentified as birds.[1]

The hypothesis that caenagnathids were birds was questioned as early as 1956 by Romer, but not corrected until Osmolska formally reclassified them as dinosaurs in 1976. Meanwhile, the classification of Oviraptor as an ornithomimid persisted unquestioned by researchers like Romer and Steel until the early 1970s when Dale Russell argued against the idea in 1972. In 1976 when Osmolska recognized Oviraptor's relationship with the Caenagnathids, she also recognized that it was not an ornithomimid and reclassified it as a member of the former family.[1] However, that same year Rinchen Barsbold argued that Oviraptor belonged to a distinct family he named the Oviraptoridae[1] and he also formally named the Oviraptorosauria later in the same year.[2]

Like their classification, the paleobiology of oviraptorosaurs has been subject to controversy and reinterpretation. The first scientifically documented Oviraptor skeleton was found lying on a nest of eggs. Because its powerful parrot-like beak appeared well-adapted to crushing hard food items and the eggs were thought to belonged to the neoceratopsian Protoceratops, oviraptorosaurs were thought to be nest-raiders that preyed on the eggs of other dinosaurs. In the 1980s, Barsbold proposed that oviraptorosaurs used their beaks to crack mollusk shells as well. In 1993, Currie and colleagues hypothesized that small vertebrate prey may have also been part of the oviraptorosaur diet. Not long after, fossil embryonic remains cast doubt on the popular reconstruction of oviraptorosaurs as egg thieves when it was discovered that the "Protoceratops" eggs that Oviraptor was thought to be "stealing" actually belonged to Oviraptor itself. The discovery of additional Oviraptor preserved on top of nests in lifelike brooding posture firmly established that oviraptorosaurs had been "framed" as egg thieves and were actually caring parents incubating their own nests.[3]

20th century

Drawing of the left arm and both hands of the

Oviraptor type specimen AMNH 6517

1920s

1923

- A specimen of the species that would come to be named Oviraptor philoceratops was found preserved on top of a nest of eggs.[3]

1924

- Osborn described the new genus and species Oviraptor philoceratops.[2] He classified it as an ornithomimid because it didn't have any teeth in its jaws[1] and interpreted the genus as being adapted to a diet of eggs.[3] Since a specimen was found preserved on top of a nest of eggs presumed to belong to Protoceratops, Osborn thought that it was smothered by a sandstorm while in the act of raiding the nest.[3]

1930s

1932

1933

1940s

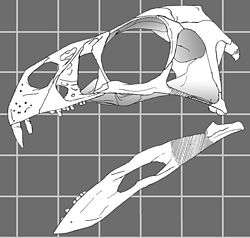

Drawing of the skull of Oviraptor, type specimen AMNH 6517

1940

1950s

1956

- Romer followed Osborn's original classification of Oviraptor as an ornithomimid. He also observed that caenagnathids had reptilian characteristics and may have been coelurosaurs.[1]

1960s

1960

- Wetmore questioned the hypothesis that caenagnathids were birds because their remains exhibit some reptilian traits.[1]

1966

- Romer continued to follow Osborn's original classification of Oviraptor as an ornithomimid.[1]

1970s

1970

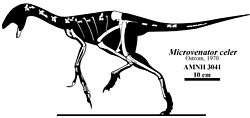

- Ostrom described the new genus and species Microvenator celer.[4]

- Steel followed Osborn's original classification of Oviraptor as an ornithomimid.[1] He also questioned the avian status of caenagnathids and proposed that they might actually be coelurosaurs instead.[1]

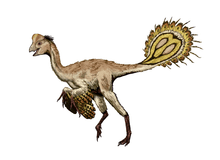

Artist's restoration of Microvenator

1971

- Cracroft named the new species Caenagnathus sternbergi.[2] He thought it was a bird.[1]

1972

- Russell argued against the classification of Oviraptor as an ornithomimid.[1]

1976

- Osmolska recognized that caenagnathids were theropods and classified Oviraptor as a member of the family.[1]

- Barsbold classified Oviraptor as a member of the new taxa Oviraptorinae and Oviraptoridae.[1]

- Barsbold named the Oviraptorosauria.[2]

1980s

1981

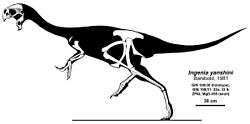

- Barsbold described the new genus and species Ingenia yanshini.[4] He also named the subfamily Ingeniinae[4] and classified the family Caenagnathidae in the Oviraptorosauria.[1]

- Osmolska described the new genus and species Elmisaurus rarus.[4]

1983

- Barsbold proposed that oviraptorosaurs used their powerful beaks to feed on shelled mollusks.[3]

1986

1988

- Currie and Russell observed that caenagnathids had arctometatarsalian feet.[3]

1990s

Fossilized Oviraptor nest, specimen AMNH FR 6508

1991

- Jerzykiewicz and Russell observed that oviraptorosaurs seem to have been most common during the Djadokhta stage.[3]

- Sabath described an oviraptorosaur nest mound.[3]

1992

- Smith interpreted the biomechanics of oviraptorosaur jaws to imply that these dinosaurs were actually herbivorous.[3]

1993

- Jerzykiewicz and others observed that oviraptorosaurs seem to have been most common in central Asia.[3]

- Currie, Godfrey, and Nessov described the new genus and species Caenagnathasia martinsoni.[2]

- Currie and others built a case for interpreting oviraptorosaurs as egg-eaters who supplemented their diet with small prey. They noted supporting traits like the animals' ability to give a "powerful nipping bite" with the front of its beak. Oviraptorosaurs also had tooth-like projections from the roof of the mouth, which resemble similar adaptations in modern egg-eating mammals.

Nesting

Citipati specimen nicknamed "Big Auntie"

- Russell and Dong argued that the Maniraptora (which includes Oviraptorosauria) was a polyphyletic assemblage of unrelated groups. Instead they classified the traditional oviraptorosaurs with the ornithomimids, therizinosauroids, and troodontids in a new, greatly expanded Oviraptorosauria.[5]

1994

- Norell and others reported the discovery of a tiny theropod skeleton in an oviraptorid nest. They suggested this find was evidence that oviraptorosaur hunted tiny game. They also noted that the supposed Protoceratops eggs of the Central Asiatic Expeditions actually preserved the embryonic remains of oviraptorosaurs.[3]

1996

- Currie reported the presence of nests of large eggs more than 40 centimetres (16 in) long in China. Oviraptorosaurs would come to be considered possible candidates for the egg layers.[3]

Fossilized Citipati egg with preserved embryo

- Dong and Currie reported the discovery of an oviraptorid from the Djadokhta Formation of northern China preserved on top of a nest of eggs. This overturned more than 60 years of interpreting the Oviraptor of the Central Asiatic Expeditions as a rapacious egg-thief in favor of it likely being a faithful mother at her nest. The researchers reconstructed the way mother oviraptorosaurs built their nests. The standing mother would lay a pair of eggs and bury them by hand. Then she would turn and repeat the process until she had made a ring of egg-pairs completely around herself. Since by then the area where she was standing would be higher than the eggs, she would repeat the process with another ring of egg-pairs as a second layer. This process would gradually build an egg mound containing as many as 30 eggs in up to three layers.[3]

1997

- Sues published a critical review of earlier interpretations of the oviraptorosaurs' evolutionary relationships and formulated the clade's first synapomorphy-based diagnosis. He also performed a cladistic analysis and found oviraptorosaurs to be the sister group of the therizinosaurs.[6]

- Sereno regarded oviraptorosaurs as maniraptorans and found them to be the sister group of Paraves (which includes deinonychosaurs and birds) in a cladistic analysis.[6]

- Padian and others published a cladistic definition for Oviraptorsauris for the first time; all taxa closer to Oviraptor than to birds.[6]

- Barsbold described the new genus Rinchenia for the species Oviraptor mongoliensis.[2] Barsbold credited Currie and Padian for defining Oviraptorosauria as the Oviraptoridae and all taxa closer to Oviraptor.[6]

1998

- Sereno regarded oviraptorosaurs as maniraptorans and found them to be the sister group of Paraves (which includes deinonychosaurs and birds) in a cladistic analysis.[6] He defined oviraptorosaurs as all maniraptorans closer to Oviraptor than to Neornithes.[6]

- Currie, Norell, and Ji described the new genus and species Caudipteryx zoui.[2]

- Ji and others reported the presence of gastroliths in Caudipteryx. These are evidence for an herbivorous diet.[3]

- Makovicky and Sues considered oviraptorosaurs to be the sister group of the therizinosaurs.[6]

1999

- Sereno found Caudipteryx to be a basal oviraptorosaur. He also erected the clade Caenagnathoidea for the caenagnathids and oviraptorids.[6]

- Elzanowski performed a cladistic analysis and found a group consisting of oviraptorosaurs, ornithomimosaurs and therizinosaurs were more closely related to birds than deinonychosaurs. No other cladistic study in the history of dinosaur research had come up with this result.[6]

- Padian and others changed the definition of Oviraptorosauria from a stem-based clade to a node-based one. They defined the oviraptorosaurs as "Oviraptor and Chirostenotes (=Caenagnathus) and all the descendents of their most recent common ancestor."[6]

- Clark and others observed that oviraptorosaurs are among the most common dinosaurs found at Ukhaa Tolgod in Mongolia.[3] They reported further specimens preserved on nests in brooding position. They suggested contrary to Dong and Currie's 1996 reconstruction of oviraptorosaur nest-building behavior that the animals may have constructed their nests by maneuvering the eggs into position by hand. However, this explanation is less parsimonious and has less evidentiary support, so it never gained favor among paleontologists.[3]

21st century

2000s

2000

2001

- Clark, Norell, and Barsbold described the new genus and species Citipati osmolskae.[4]

- Clark, Norell, and Barsbold described the new genus and species Khaan mckennai.[4]

- David J. Varrichio reported the first occurrences of oviraptorosaurs from Montana.[7] The first find was an articular region from the lower jaw of Caenagnathus sternbergi of Campanian age from the Two Medicine Formation.[7] This species had previously only been known from the Canadian province of Alberta.[7] Another new Montanan oviraptorosaur specimen, a foot found in the Hell Creek Formation, was assigned to Leptorhynchus elegans (as Elmisaurus elegans).[7]

- Kevin Padian, Ji Qiang and Ji Shu-an published a review of known feathered dinosaurs and their implications for the origin of flight.[8] The authors observe that many aspects of the distribution of feather homologues meet the expectations of earlier phylogenetic hypotheses, including a gradual transition from primitive filaments in Sinosauropteryx to the shared filaments and "rudimentary" true feathers in Caudipteryx and Protarchaeopteryx, to flight feathers in Archaeopteryx.[9] The team speculates that the plumulaceous feathers in Cauditeryx and Protarchaeopteryx may have originated as tufts of Sinosauropteryx-style filaments, the shafts of which possibly formed by the consolidation of individual filaments.[10] The parallel nature of the barbs in Caudipteryx and Protarcheopteryx suggest the existence of barbules.[11] This suggests that barbules, which are necessary for flight-worthy wings, evolved prior to flight.[11]

| Cladogram of feathered dinosaurs from Padian et al. 2001 |

| Feathered Dinosaurs |

|

|

| Taxa marked with a P were known to bear plumulaceous or pennaceous feathers at the time of the study. Taxa marked with F were known to bear simple filamentous integumentary structures. |

|

2000

- 2002? Maryanska and others confirmed Sereno's finding that Caudipteryx was an oviraptorosaur. They also found Avimimus to be an oviraptorosaur as well.[6]

2002

- Xu and others described the new genus and species Incisivosaurus gauthieri.[2] Their research supported recent findings that Caudipteryx and Avimimus were oviraptorosaurs.[6]

- Maryanska and others performed a cladistic analysis that found oviraptorosaurs to be avialans.[6]

- Zelenitsky and others studied the shape and shell histology of the large fossil eggs reported from China by Currie in 1996 and concluded that they may have been laid by oviraptorosaurs. Given their large size, this implied that giant oviraptorosaurs remained to be discovered.[3]

2003

2004

2005

2007

2008

2009

2010s

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016

See also

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Osmolska, Currie, and Barsbold (2004); "Systematics and Evolution", page 178.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Osmolska, Currie, and Barsbold (2004); "Table 8.1: Oviraptorosauria", page 166.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Osmolska, Currie, and Barsbold (2004); "Paleoecology", page 183.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Osmolska, Currie, and Barsbold (2004); "Table 8.1: Oviraptorosauria", page 167.

- ↑ Osmolska, Currie, and Barsbold (2004); "Systematics and Evolution", pages 178-179.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Osmolska, Currie, and Barsbold (2004); "Systematics and Evolution", page 179.

- 1 2 3 4 Varricchio (2001); "Abstract," page 42.

- ↑ Padian, Ji, and Ji (2001); "Abstract," page 117.

- ↑ Padian, Ji, and Ji (2001); "Conclusions," pages 131-132.

- ↑ Padian, Ji, and Ji (2001); "Possible Evolutionary Sequence from Protofeathers to True Feathers," page 126.

- 1 2 Padian, Ji, and Ji (2001); "Possible Evolutionary Sequence from Protofeathers to True Feathers," page 127.

- ↑ Lü et al. (2004); "Abstract," page 95.

- ↑ Zanno and Sampson (2005); "Abstract," page 897.

- ↑ Lü et al. (2005); "Abstract," page 51.

- ↑ Lü and Zhang (2005); "Abstract," page 412.

- ↑ Xu et al. (2007); "Abstract," page 844.

- ↑ He, Wang, and Zhou (2008); "Abstract," page 178.

- ↑ Lü et al. (2009); "Abstract," page 43.

- ↑ Xu and Han (2010); "Abstract," page 11.

- ↑ Longrich, Currie, and Dong (2010); "Abstract," page 23.

- 1 2 Sullivan, Jasinski and Van Tomme (2011); "Abstract," page 418.

- ↑ Ji et al. (2012); "Abstract," page 2102.

- ↑ Easter (2013); "Abstract," page 184.

- ↑ Wang et al. (2013); "Abstract," page 242.

- ↑ Wei et al. (2013); "Abstract," page 11.

- ↑ Longrich et al. (2013); "Abstract," page 899.

- ↑ Lü et al. (2013b); "Abstract," page 1.

- ↑ Xu et al. (2013); "Abstract," page 85.

- ↑ Lü et al. (2013a); "Abstract," page 165.

- ↑ Lamanna et al. (2014); "Abstract," page 1.

- ↑ Lü et al. (2015); in passim.

- ↑ Funston and Currie (2016); in passim.

- ↑ Lü et al. (2016); in passim.

References

- Easter, J. (2013). "A new name for the oviraptorid dinosaur "Ingenia" yanshini (Barsbold, 1981; preoccupied by Gerlach, 1957)". Zootaxa. 3737 (2): 184–190. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.3737.2.6.

- Gregory F. Funston & Philip J. Currie (2016). "A new caenagnathid (Dinosauria: Oviraptorosauria) from the Horseshoe Canyon Formation of Alberta, Canada, and a reevaluation of the relationships of Caenagnathidae". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. Online edition: e1160910. doi:10.1080/02724634.2016.1160910.

- He, T., Wang, X.-L., and Zhou, Z.-H. (2008). "A new genus and species of caudipterid dinosaur from the Lower Cretaceous Jiufotang Formation of western Liaoning, China" (PDF). Vertebrata PalAsiatica. 46 (3): 178–189. Retrieved 2012-10-20.

- Ji Qiang, Lü Jun-Chang, Wei Xue-Fang, Wang Xu-Ri (2012). "A new oviraptorosaur from the Yixian Formation of Jianchang, Western Liaoning Province, China". Geological Bulletin of China. 31 (12): 2102–2107.

- Lamanna, M. C.; Sues, H. D.; Schachner, E. R.; Lyson, T. R. (2014). "A New Large-Bodied Oviraptorosaurian Theropod Dinosaur from the Latest Cretaceous of Western North America". PLoS ONE. 9 (3): e92022. PMC 3960162

. PMID 24647078. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0092022.

. PMID 24647078. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0092022.

- Nicholas R. Longrich, Philip J. Currie, Dong Zhi-Ming (2010). "A new oviraptorid (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Upper Cretaceous of Bayan Mandahu, Inner Mongolia". Palaeontology. 53 (5): 945–960. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2010.00968.x.

- Longrich, N. R.; Barnes, K.; Clark, S.; Millar, L. (2013). "Caenagnathidae from the Upper Campanian Aguja Formation of West Texas, and a Revision of the Caenagnathinae". Bulletin of the Peabody Museum of Natural History. 54: 23–49. doi:10.3374/014.054.0102.

- Lü, J.; Currie, P. J.; Xu, L.; Zhang, X.; Pu, H.; Jia, S. (2013). "Chicken-sized oviraptorid dinosaurs from central China and their ontogenetic implications". Naturwissenschaften. 100 (2): 165–175. Bibcode:2013NW....100..165L. PMID 23314810. doi:10.1007/s00114-012-1007-0.

- Lü, J.; Tomida, Y.; Azuma, Y.; Dong, Z.; Lee, Y.-N. (2004). "New oviraptorid dinosaur (Dinosauria: Oviraptorosauria) from the Nemegt Formation of southwestern Mongolia". Bulletin of the National Science Museum, Tokyo, Series C. 30: 95–130.

- Lü; Xu, L.; Jiang, X.; Jia, S.; Li, M.; Yuan, C.; Zhang, X.; Ji, Q. (2009). "A preliminary report on the new dinosaurian fauna from the Cretaceous of the Ruyang Basin, Henan Province of central China". Journal of the Palaeontological Society of Korea. 25: 43–56.

- Lü, J.; Yi, L.; Zhong, H.; Wei, X. (2013). Dodson, Peter, ed. "A New Oviraptorosaur (Dinosauria: Oviraptorosauria) from the Late Cretaceous of Southern China and Its Paleoecological Implications". PLoS ONE. 8 (11): e80557. PMC 3842309

. PMID 24312233. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0080557.

. PMID 24312233. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0080557.

- Lü, J.; Tomida, Y.; Azuma, Y.; Dong, Z.; Lee, Y.-N.; et al. (2005). "Nemegtomaia gen. nov., a replacement name for the oviraptorosaurian dinosaur Nemegtia Lü et al., 2004, a preoccupied name". Bulletin of the National Science Museum, Tokyo, Series C. 31: 51.

- Lü, Junchang; Pu, Hanyong; Kobayashi, Yoshitsugu; Xu, Li; Chang, Huali; Shang, Yuhua; Liu, Di; Lee, Yuong-Nam; Kundrát, Martin; Shen, Caizhi (2015). "A New Oviraptorid Dinosaur (Dinosauria: Oviraptorosauria) from the Late Cretaceous of Southern China and Its Paleobiogeographical Implications". Scientific Reports. 5: Article number 11490. PMC 4489096

. PMID 26133245. doi:10.1038/srep11490.

. PMID 26133245. doi:10.1038/srep11490.

- Junchang Lü, Rongjun Chen, Stephen L. Brusatte, Yangxiao Zhu, Caizhi Shen (2016). "A Late Cretaceous diversification of Asian oviraptorid dinosaurs: evidence from a new species preserved in an unusual posture". Scientific Reports. 6: Article number 35780. PMC 5103654

. PMID 27831542. doi:10.1038/srep35780.

. PMID 27831542. doi:10.1038/srep35780.

- Lu, J.; Zhang, B.-K. (2005). "A new oviraptorid (Theropoda: Oviraptorosauria) from the Upper Cretaceous of the Nanxiong Basin, Guangdong Province of southern China". Acta Palaeontologica Sinica. 44 (3): 412–422.

- Osmólska, Halszka; Currie, Philip J.; Barsbold, Rinchen (2004). "Oviraptorosauria". In Weishampel, D. B.; Dodson, P.; Osmolska, H. The Dinosauria (2 ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 165–193. ISBN 978-0520254084.

- Padian, K.; Ji, Qiang; Ji, Shu-An (2001). "Feathered dinosaurs and origin of flight". In Tanke, D. H.; Carpenter, K. Mesozoic Vertebrate Life. Life of the Past. Indiana University Press. pp. 117–135.

- Robert M. Sullivan, Steven E. Jasinski and Mark P.A. Van Tomme (2011). "A new caenagnathid Ojoraptorsaurus boerei, n. gen., n. sp. (Dinosauria, Oviraptorosauria), from the Upper Ojo Alamo Formation (Naashoibito Member), San Juan Basin, New Mexico" (PDF). Fossil Record 3. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin. 53: 418–428.

- Varrichio, D. J. (2001). "Late Cretaceous oviraptorosaur (Theropoda) dinosaurs from Montana". In Tanke, D. H.; Carpenter, K. Mesozoic Vertebrate Life. Life of the Past. Indiana University Press. pp. 42–57.

- Wang, S.; Sun, C.; Sullivan, C.; Xu, X. (2013). "A new oviraptorid (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Upper Cretaceous of southern China". Zootaxa. 3640 (2): 242. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.3640.2.7.

- Wei Xuefang, Pu Hanyong, Xu Li, Liu Di and Lü Junchang (2013). "A New Oviraptorid Dinosaur (Theropoda: Oviraptorosauria) from the Late Cretaceous of Jiangxi Province, Southern China". Acta Geologica Sinica (English Edition). 87 (4): 899–904. doi:10.1111/1755-6724.12098.

- Xu, X.; Han, F.-L. (2010). "A new oviraptorid dinosaur (Theropoda: Oviraptorosauria) from the Upper Cretaceous of China". Vertebrata PalAsiatica. 48 (1): 11–18.

- Xu Xing, Tan Qing-Wei, Wang Shuo, Corwin Sullivan, David W. E. Hone, Han Feng-Lu, Ma Qing-Yu, Tan Lin and Xiao Dong (2013). "A new oviraptorid from the Upper Cretaceous of Nei Mongol, China, and its stratigraphic implications" (PDF). Vertebrata PalAsiatica. 51 (2): 85–101.

- Xu, X.; Tan, Q.; Wang, J.; Zhao, X.; Tan, L. (2007). "A gigantic bird-like dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous of China". Nature. 447 (7146): 844–847. PMID 17565365. doi:10.1038/nature05849.

- Zanno, Lindsay E.; Sampson, Scott D. (2005). "A new oviraptorosaur (Theropoda; Maniraptora) from the Late Cretaceous (Campanian) of Utah". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 25 (4): 897–904. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2005)025[0897:ANOTMF]2.0.CO;2.

External links

Nesting Citipati specimen nicknamed "Big Auntie"

Nesting Citipati specimen nicknamed "Big Auntie" Fossilized Citipati egg with preserved embryo

Fossilized Citipati egg with preserved embryo

. PMID 24647078. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0092022.

. PMID 24647078. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0092022. . PMID 24312233. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0080557.

. PMID 24312233. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0080557. . PMID 26133245. doi:10.1038/srep11490.

. PMID 26133245. doi:10.1038/srep11490. . PMID 27831542. doi:10.1038/srep35780.

. PMID 27831542. doi:10.1038/srep35780. Media related to Ornithomimosauria at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Ornithomimosauria at Wikimedia Commons