Time dilation

According to the theory of relativity, time dilation is a difference in the elapsed time measured by two observers, either due to a velocity difference relative to each other, or by being differently situated relative to a gravitational field. As a result of the nature of spacetime,[2] a clock that is moving relative to an observer will be measured to tick slower than a clock that is at rest in the observer's own frame of reference. A clock that is under the influence of a stronger gravitational field than an observer's will also be measured to tick slower than the observer's own clock.

Such time dilation has been repeatedly demonstrated, for instance by small disparities in a pair of atomic clocks after one of them is sent on a space trip, or by clocks on the Space Shuttle running slightly slower than reference clocks on Earth, or clocks on GPS and Galileo satellites running slightly faster.[1][3][4] Time dilation has also been the subject of science fiction works, as it technically provides the means for forward time travel.[5]

Velocity time dilation

Special relativity indicates that, for an observer in an inertial frame of reference, a clock that is moving relative to him will be measured to tick slower than a clock that is at rest in his frame of reference. This case is sometimes called special relativistic time dilation. The faster the relative velocity, the greater the time dilation between one another, with the rate of time reaching zero as one approaches the speed of light (299,792,458 m/s). This causes massless particles that travel at the speed of light to be unaffected by the passage of time.

Theoretically, time dilation would make it possible for passengers in a fast-moving vehicle to advance further into the future in a short period of their own time. For sufficiently high speeds, the effect is dramatic.[2] For example, one year of travel might correspond to ten years on Earth. Indeed, a constant 1 g acceleration would permit humans to travel through the entire known Universe in one human lifetime.[7] Space travelers could then return to Earth billions of years in the future. A scenario based on this idea was presented in the novel Planet of the Apes by Pierre Boulle, and the Orion Project has been an attempt toward this idea.

With current technology severely limiting the velocity of space travel, however, the differences experienced in practice are minuscule: after 6 months on the International Space Station (ISS) (which orbits Earth at a speed of about 7,700 m/s[8]) an astronaut would have aged about 0.005 seconds less than those on Earth. The Hafele and Keating experiment involved flying planes around the world with atomic clocks on board. Upon the trips' completion the clocks were compared to a static, ground based atomic clock. It was found that 273±7 nanoseconds had been gained on the planes' clocks.[9] The current human time travel record holder is Russian cosmonaut Sergei Krikalev,[10] who beat the previous record of about 20 milliseconds by cosmonaut Sergei Avdeyev.[11]

Simple inference of velocity time dilation

Right: Events according to an observer moving to the left of the setup: bottom mirror A when signal is generated at time t'=0, top mirror B when signal gets reflected at time t'=D/c, bottom mirror A when signal returns at time t'=2D/c

Time dilation can be inferred from the observed constancy of the speed of light in all reference frames dictated by the second postulate of special relativity.[12][13][14][15]

This constancy of the speed of light means that, counter to intuition, speeds of material objects and light are not additive. It is not possible to make the speed of light appear greater by approaching at speed towards the source of said light, and likewise, it is not possible to make the speed of light appear any less by receding from the source.

Consider then, a simple clock consisting of two mirrors A and B, between which a light pulse is bouncing. The separation of the mirrors is L and the clock ticks once each time the light pulse hits either of the mirrors.

In the frame in which the clock is at rest (diagram on the left), the light pulse traces out a path of length 2L and the period of the clock is 2L divided by the speed of light:

From the frame of reference of a moving observer traveling at the speed v relative to the resting frame of the clock (diagram at right), the light pulse is seen as tracing out a longer, angled path. Keeping the speed of light constant for all inertial observers, requires a lengthening of the period of this clock from the moving observer's perspective. That is to say, in a frame moving relative to the local clock, this clock will appear to be running more slowly. Straightforward application of the Pythagorean theorem leads to the well-known prediction of special relativity:

The total time for the light pulse to trace its path is given by

The length of the half path can be calculated as a function of known quantities as

Elimination of the variables D and L from these three equations results in

which expresses the fact that the moving observer's period of the clock is longer than the period in the frame of the clock itself.

Reciprocity

Given a certain frame of reference, and the "stationary" observer described earlier, if a second observer accompanied the "moving" clock, each of the observers would perceive the other's clock as ticking at a slower rate than their own local clock, due to them both perceiving the other to be the one that's in motion relative to their own stationary frame of reference.

Common sense would dictate that, if the passage of time has slowed for a moving object, said object would observe the external world's time to be correspondingly sped up. Counterintuitively, special relativity predicts the opposite. When two observers are in motion relative to each other, each will se the other's clock slowing down, in concordance with them being moving relative to the observer's frame of reference.

While this seems self-contradictory, a similar oddity occurs in everyday life. If person A sees person B, person B will appear small to them; at the same time, person A will appear small to person B. Being familiar with the effects of perspective, we see no contradiction or paradox in this situation.[16]

The reciprocity of the phenomenon also leads to the so called twins paradox, where one person staying on Earth and one embarking on space travel should apparently expect each other to age the same amount of time since they both see the other as moving at equal speeds from their own frame of reference. The dilemma posed by the paradox, however, can be explained by the acceleration changes inherent to the traveling person's trip, which not constituting an intertial frame of reference, is not covered by special relativity.

Experimental testing

- Ives and Stilwell (1938, 1941). The stated purpose of these experiments was to verify the time dilation effect, predicted by Larmor–Lorentz ether theory, due to motion through the ether using Einstein's suggestion that Doppler effect in canal rays would provide a suitable experiment. These experiments measured the Doppler shift of the radiation emitted from cathode rays, when viewed from directly in front and from directly behind. The high and low frequencies detected were not the classically predicted values

- The high and low frequencies of the radiation from the moving sources were measured as[17]

- as deduced by Einstein (1905) from the Lorentz transformation, when the source is running slow by the Lorentz factor.

- Rossi and Hall (1941) compared the population of cosmic-ray-produced muons at the top of a mountain to that observed at sea level. Although the travel time for the muons from the top of the mountain to the base is several muon half-lives, the muon sample at the base was only moderately reduced. This is explained by the time dilation attributed to their high speed relative to the experimenters. That is to say, the muons were decaying about 10 times slower than if they were at rest with respect to the experimenters.

- Hasselkamp, Mondry, and Scharmann[18] (1979) measured the Doppler shift from a source moving at right angles to the line of sight. The most general relationship between frequencies of the radiation from the moving sources is given by:

- as deduced by Einstein (1905).[19] For ϕ = 90° (cosϕ = 0) this reduces to fdetected = frestγ. This lower frequency from the moving source can be attributed to the time dilation effect and is often called the transverse Doppler effect and was predicted by relativity.

- In 2010 time dilation was observed at speeds of less than 10 meters per second using optical atomic clocks connected by 75 meters of optical fiber.[20]

- A comparison of muon lifetimes at different speeds is possible. In the laboratory, slow muons are produced; and in the atmosphere, very fast moving muons are introduced by cosmic rays. Taking the muon lifetime at rest as the laboratory value of 2.197 μs, the lifetime of a cosmic ray produced muon traveling at 98% of the speed of light is about five times longer, in agreement with observations.[21] In the muon storage ring at CERN the lifetime of muons circulating with γ = 29.327 was found to be dilated to 64.378 μs, confirming time dilation to an accuracy of 0.9 ± 0.4 parts per thousand.[22] In this experiment the "clock" is the time taken by processes leading to muon decay, and these processes take place in the moving muon at its own "clock rate", which is much slower than the laboratory clock.

Proper time and Minkowski diagram

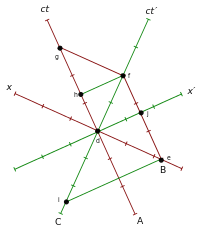

In the Minkowski diagram from the second image on the right, clock C resting in inertial frame S′ meets clock A at d and clock B at f (both resting in S). All three clocks simultaneously start to tick in S. The worldline of A is the ct-axis, the worldline of B intersecting f is parallel to the ct-axis, and the worldline of C is the ct′-axis. All events simultaneous with d in S are on the x-axis, in S′ on the x′-axis.

The proper time between two events is indicated by a clock present at both events.[23] It is invariant, i.e., in all inertial frames it is agreed that this time is indicated by that clock. Interval df is therefore the proper time of clock C, and is shorter with respect to the coordinate times ef=dg of clocks B and A in S. Conversely, also proper time ef of B is shorter with respect to time if in S′, because event e was measured in S′ already at time i due to relativity of simultaneity, long before C started to tick.

From that it can be seen, that the proper time between two events indicated by an unaccelerated clock present at both events, compared with the synchronized coordinate time measured in all other inertial frames, is always the minimal time interval between those events. However, the interval between two events can also correspond to the proper time of accelerated clocks present at both events. Under all possible proper times between two events, the proper time of the unaccelerated clock is maximal, which is the solution to the twin paradox.[23]

Formulation

The formula for determining time dilation in special relativity is:

where Δt is the time interval between two co-local events (i.e. happening at the same place) for an observer in some inertial frame (e.g. ticks on his clock), known as the proper time, Δt′ is the time interval between those same events, as measured by another observer, inertially moving with velocity v with respect to the former observer, v is the relative velocity between the observer and the moving clock, c is the speed of light, and the Lorentz factor (conventionally denoted by the Greek letter gamma or γ) is

Thus the duration of the clock cycle of a moving clock is found to be increased: it is measured to be "running slow". The range of such variances in ordinary life, where v ≪ c, even considering space travel, are not great enough to produce easily detectable time dilation effects and such vanishingly small effects can be safely ignored for most purposes. It is only when an object approaches speeds on the order of 30,000 km/s (1/10 the speed of light) that time dilation becomes important.

Time dilation by the Lorentz factor was predicted by Joseph Larmor (1897), at least for electrons orbiting a nucleus. Thus "... individual electrons describe corresponding parts of their orbits in times shorter for the [rest] system in the ratio :" (Larmor 1897). Time dilation of magnitude corresponding to this (Lorentz) factor has been experimentally confirmed, as described below.

Hyperbolic motion

In special relativity, time dilation is most simply described in circumstances where relative velocity is unchanging. Nevertheless, the Lorentz equations allow one to calculate proper time and movement in space for the simple case of a spaceship which is applied with a force per unit mass, relative to some reference object in uniform (i.e. constant velocity) motion, equal to g throughout the period of measurement.

Let t be the time in an inertial frame subsequently called the rest frame. Let x be a spatial coordinate, and let the direction of the constant acceleration as well as the spaceship's velocity (relative to the rest frame) be parallel to the x-axis. Assuming the spaceship's position at time t = 0 being x = 0 and the velocity being v0 and defining the following abbreviation

the following formulas hold:[24]

Position:

Velocity:

Proper time:

In the case where v(0) = v0 = 0 and τ(0) = τ0 = 0 the integral can be expressed as a logarithmic function or, equivalently, as an inverse hyperbolic function:

Gravitational time dilation

Gravitational time dilation is experienced by an observer that, being under the influence of a gravitational field, will see his own clock slow down, compared to another that's under a weaker gravitational field.

Gravitational time dilation is at play e.g. for ISS astronauts. While the astronauts' relative velocity slows down their time, the reduced gravitational influence at their location speeds it up, although at a lesser degree. Also, a climber's time is theoretically passing slightly faster at the top of a mountain compared to people at sea level. It has also been calculated that due to time dilation, the core of the Earth is 2.5 years younger than the crust.[25] Travel to regions of space where gravitational time dilation is taking place, such as within the gravitational field of a black hole, yet still outside the event horizon, perhaps on a hyperbolic trajectory exiting the field, could yield time-shifting results analogous to those of near-lightspeed space travel.

Contrarily to velocity time dilation, in which both observers see the other as moving slower (a reciprocal effect), gravitational time dilation is not reciprocal. This means that with gravitational time dilation both observers agree that the clock nearer the center of the gravitational field is slower in rate, and they agree on the ratio of the difference.

Experimental testing

- In 1959 Robert Pound and Glen A. Rebka measured the very slight gravitational red shift in the frequency of light emitted at a lower height, where Earth's gravitational field is relatively more intense. The results were within 10% of the predictions of general relativity. In 1964, Pound and J. L. Snider measured a result within 1% of the value predicted by gravitational time dilation.[26] (See Pound–Rebka experiment)

- In 2010 gravitational time dilation was measured at the earth's surface with a height difference of only one meter, using optical atomic clocks.[20]

Combined effect of velocity and gravitational time dilation

High accuracy timekeeping, low earth orbit satellite tracking, and pulsar timing are applications that require the consideration of the combined effects of mass and motion in producing time dilation. Practical examples include the International Atomic Time standard and its relationship with the Barycentric Coordinate Time standard used for interplanetary objects.

Relativistic time dilation effects for the solar system and the earth can be modeled very precisely by the Schwarzschild solution to the Einstein field equations. In the Schwarzschild metric, the interval is given by[28][29]

where

- is a small increment of proper time (an interval that could be recorded on an atomic clock),

- is a small increment in the coordinate (coordinate time),

- are small increments in the three coordinates of the clock's position,

- represents the sum of the Newtonian gravitational potentials due to the masses in the neighborhood, based on their distances from the clock. This sum includes any tidal potentials.

The coordinate velocity of the clock is given by

The coordinate time is the time that would be read on a hypothetical "coordinate clock" situated infinitely far from all gravitational masses (), and stationary in the system of coordinates (). The exact relation between the rate of proper time and the rate of coordinate time for a clock with a radial component of velocity is

where

- is the radial velocity,

- is the Newtonian potential, equivalent to half of the escape velocity squared.

The above equation is exact under the assumptions of the Schwarzschild solution.

Experimental testing

- Hafele and Keating, in 1971, flew caesium atomic clocks east and west around the earth in commercial airliners, to compare the elapsed time against that of a clock that remained at the U.S. Naval Observatory. Two opposite effects came into play. The clocks were expected to age more quickly (show a larger elapsed time) than the reference clock, since they were in a higher (weaker) gravitational potential for most of the trip (c.f. Pound–Rebka experiment). But also, contrastingly, the moving clocks were expected to age more slowly because of the speed of their travel. From the actual flight paths of each trip, the theory predicted that the flying clocks, compared with reference clocks at the U.S. Naval Observatory, should have lost 40±23 nanoseconds during the eastward trip and should have gained 275±21 nanoseconds during the westward trip. Relative to the atomic time scale of the U.S. Naval Observatory, the flying clocks lost 59±10 nanoseconds during the eastward trip and gained 273±7 nanoseconds during the westward trip (where the error bars represent standard deviation).[30] In 2005, the National Physical Laboratory in the United Kingdom reported their limited replication of this experiment.[31] The NPL experiment differed from the original in that the caesium clocks were sent on a shorter trip (London–Washington, D.C. return), but the clocks were more accurate. The reported results are within 4% of the predictions of relativity, within the uncertainty of the measurements.

- The Global Positioning System can be considered a continuously operating experiment in both special and general relativity. The in-orbit clocks are corrected for both special and general relativistic time dilation effects as described above, so that (as observed from the earth's surface) they run at the same rate as clocks on the surface of the Earth.[32]

Footnotes

References

- 1 2 3 Ashby, Neil (2003). "Relativity in the Global Positioning System" (PDF). Living Reviews in Relativity. 6: 16. Bibcode:2003LRR.....6....1A. doi:10.12942/lrr-2003-1.

- 1 2 Toothman, Jessika. "How Do Humans age in space?". HowStuffWorks. Retrieved 2012-04-24.

- ↑ Toothman, Jessika. "How Do Humans age in space?". HowStuffWorks. Retrieved 2012-04-24.

- ↑ Lu, Ed. "Expedition 7 – Relativity". Ed's Musing from Space. NASA. Retrieved 2012-04-24.

- ↑ "spaceplace.nasa.gov".

- ↑ Hraskó, Péter (2011). Basic Relativity: An Introductory Essay (illustrated ed.). Springer Science & Business Media. p. 60. ISBN 978-3-642-17810-8. Extract of page 60

- ↑ Calder, Nigel (2006). Magic Universe: A grand tour of modern science. Oxford University Press. p. 378. ISBN 0-19-280669-6.

- ↑ Lu, Ed. "Expedition 7 – Relativity". Ed's Musing from Space. NASA. Retrieved 2015-01-20.

- ↑ "Hafele and Keating Experiment". NA. Retrieved 2015-02-04.

- ↑ Overbye, Dennis (2005-06-28). "A Trip Forward in Time. Your Travel Agent: Einstein.". The New York Times. Retrieved 2015-12-08.

- ↑ Gott, J., Richard (2002). Time Travel in Einstein's Universe. p. 75.

- ↑ Cassidy, David C.; Holton, Gerald James; Rutherford, Floyd James (2002). Understanding Physics. Springer-Verlag. p. 422. ISBN 0-387-98756-8.

- ↑ Cutner, Mark Leslie (2003). Astronomy, A Physical Perspective. Cambridge University Press. p. 128. ISBN 0-521-82196-7.

- ↑ Lerner, Lawrence S. (1996). Physics for Scientists and Engineers, Volume 2. Jones and Bartlett. pp. 1051–1052. ISBN 0-7637-0460-1.

- ↑ Ellis, George F. R.; Williams, Ruth M. (2000). Flat and Curved Space-times (2n ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 28–29. ISBN 0-19-850657-0.

- ↑ Adams, Steve (1997). Relativity: An introduction to space-time physics. CRC Press. p. 54. ISBN 0-7484-0621-2.

- ↑ Blaszczak, Z. (2007). Laser 2006. Springer. p. 59. ISBN 3540711139.

- ↑ Hasselkamp, D.; Mondry, E.; Scharmann, A. (1979). "Direct observation of the transversal Doppler-shift". Zeitschrift für Physik A. 289 (2): 151–155. Bibcode:1979ZPhyA.289..151H. doi:10.1007/BF01435932.

- ↑ Einstein, A. (1905). "On the electrodynamics of moving bodies". Fourmilab.

- 1 2 Chou, C. W.; Hume, D. B.; Rosenband, T.; Wineland, D. J. (2010). "Optical Clocks and Relativity". Science. 329 (5999): 1630–1633. Bibcode:2010Sci...329.1630C. PMID 20929843. doi:10.1126/science.1192720.

- ↑ Stewart, J. V. (2001). Intermediate electromagnetic theory. World Scientific. p. 705. ISBN 981-02-4470-3.

- ↑ Bailey, J. et al. Nature 268, 301 (1977)

- 1 2 Edwin F. Taylor, John Archibald Wheeler (1992). Spacetime Physics: Introduction to Special Relativity. New York: W. H. Freeman. ISBN 0-7167-2327-1.

- ↑ See equations 3, 4, 6 and 9 of Iorio, Lorenzo (2004). "An analytical treatment of the Clock Paradox in the framework of the Special and General Theories of Relativity". Foundations of Physics Letters. 18: 1–19. Bibcode:2005FoPhL..18....1I. arXiv:physics/0405038

. doi:10.1007/s10702-005-2466-8.

. doi:10.1007/s10702-005-2466-8. - ↑ "New calculations show Earth's core is much younger than thought". Phys.org. 26 May 2016.

- ↑ Pound, R. V.; Snider J. L. (November 2, 1964). "Effect of Gravity on Nuclear Resonance". Physical Review Letters. 13 (18): 539–540. Bibcode:1964PhRvL..13..539P. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.13.539.

- ↑ Ashby, Neil (2002). "Relativity in the Global Positioning System". Physics Today. 55 (5): 45. Bibcode:2002PhT....55e..41A. doi:10.1063/1.1485583.

- ↑ See equations 2 & 3 (combined here and divided throughout by c2) at pp. 35–36 in Moyer, T. D. (1981). "Transformation from proper time on Earth to coordinate time in solar system barycentric space-time frame of reference". Celestial Mechanics. 23: 33–56. Bibcode:1981CeMec..23...33M. doi:10.1007/BF01228543.

- ↑ A version of the same relationship can also be seen at equation 2 in Ashbey, Neil (2002). "Relativity and the Global Positioning System" (PDF). Physics Today. 55 (5): 45. Bibcode:2002PhT....55e..41A. doi:10.1063/1.1485583.

- ↑ Nave, C. R. (22 August 2005). "Hafele and Keating Experiment". HyperPhysics. Retrieved 2013-08-05.

- ↑ "Einstein" (PDF). Metromnia. National Physical Laboratory. 2005. pp. 1–4.

- ↑ Kaplan, Elliott; Hegarty, Christopher (2005). Understanding GPS: Principles and Applications. Artech House. p. 306. ISBN 1-58053-895-9. Extract of page 306

Further reading

- Callender, C.; Edney, R. (2001). Introducing Time. Icon Books. ISBN 1-84046-592-1.

- Einstein, A. (1905). "Zur Elektrodynamik bewegter Körper". Annalen der Physik. 322 (10): 891. Bibcode:1905AnP...322..891E. doi:10.1002/andp.19053221004.

- Einstein, A. (1907). "Über die Möglichkeit einer neuen Prüfung des Relativitätsprinzips". Annalen der Physik. 328 (6): 197–198. Bibcode:1907AnP...328..197E. doi:10.1002/andp.19073280613.

- Hasselkamp, D.; Mondry, E.; Scharmann, A. (1979). "Direct Observation of the Transversal Doppler-Shift". Zeitschrift für Physik A. 289 (2): 151–155. Bibcode:1979ZPhyA.289..151H. doi:10.1007/BF01435932.

- Ives, H. E.; Stilwell, G. R. (1938). "An experimental study of the rate of a moving clock". Journal of the Optical Society of America. 28 (7): 215–226. doi:10.1364/JOSA.28.000215.

- Ives, H. E.; Stilwell, G. R. (1941). "An experimental study of the rate of a moving clock. II". Journal of the Optical Society of America. 31 (5): 369–374. doi:10.1364/JOSA.31.000369.

- Joos, G. (1959). "Lehrbuch der Theoretischen Physik, Zweites Buch" (11th ed.).

|chapter=ignored (help) - Larmor, J. (1897). "On a dynamical theory of the electric and luminiferous medium". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. 190: 205–300. Bibcode:1897RSPTA.190..205L. doi:10.1098/rsta.1897.0020. (third and last in a series of papers with the same name).

- Poincaré, H. (1900). "La théorie de Lorentz et le principe de Réaction". Archives Néerlandaises. 5: 253–78.

- Puri, A. (2015). "Einstein versus the simple pendulum formula: does gravity slow all clocks?". Physics Education. 50 (4): 431. Bibcode:2015PhyEd..50..431P. doi:10.1088/0031-9120/50/4/431.

- Reinhardt, S.; et al. (2007). "Test of relativistic time dilation with fast optical atomic clocks at different velocities" (PDF). Nature Physics. 3 (12): 861–864. Bibcode:2007NatPh...3..861R. doi:10.1038/nphys778.

- Rossi, B.; Hall, D. B. (1941). "Variation of the Rate of Decay of Mesotrons with Momentum". Physical Review. 59 (3): 223. Bibcode:1941PhRv...59..223R. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.59.223.

- Weiss, M. "Two way time transfer for satellites". National Institute of Standards and Technology.

- Voigt, W. (1887). "Über das Doppler'sche princip". Nachrichten von der Königlicher Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften zu Göttingen. 2: 41–51.

External links

- Online Time Dilation Calculator

- Proper Time

- Merrifield, Michael. "Lorentz Factor (and time dilation)". Sixty Symbols. Brady Haran for the University of Nottingham.