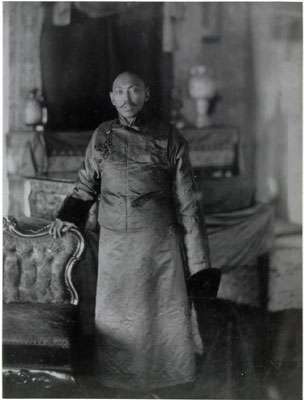

13th Dalai Lama

| Thubten | |

|---|---|

| 13th Dalai Lama | |

| |

| Reign | 31 July 1879 – 17 December 1933 |

| Predecessor | Trinley Gyatso |

| Successor | Tenzin Gyatso |

| Tibetan | ཐུབ་བསྟན་རྒྱ་མཚོ་ |

| Wylie | thub bstan rgya mtsho |

| Pronunciation | [tʰuptɛ̃ catsʰɔ] |

| Transcription (PRC) | Tubdain Gyaco |

| THDL | Thubten Gyatso |

| Chinese | 土登嘉措 |

| Pinyin | Tudeng Jiācuò |

| Born |

12 February 1876 Thakpo Langdun, Ü-Tsang, Tibet |

| Died |

17 December 1933 (aged 57) Lhasa, Tibet |

| Part of a series on |

| Tibetan Buddhism |

|---|

|

|

Practices and attainment |

|

History and overview |

|

Thubten Gyatso (Tibetan: ཐུབ་བསྟན་རྒྱ་མཚོ་, Wylie: Thub Bstan Rgya Mtsho ; 12 February 1876 – 17 December 1933) was the 13th Dalai Lama of Tibet.[1]

In 1878 he was recognized as the reincarnation of the Dalai Lama. He was escorted to Lhasa and given his pre-novice vows by the Panchen Lama, Tenpai Wangchuk, and named "Ngawang Lobsang Thupten Gyatso Jigdral Chokley Namgyal". In 1879 he was enthroned at the Potala Palace, but did not assume political power until 1895,[2] after he had reached his maturity.

Thubten Gyatso was an intellectual reformer who proved himself a skillful politician when Tibet became a pawn in British and Russian rivalry. He was responsible for countering the British expedition to Tibet, restoring discipline in monastic life, and increasing the number of lay officials to avoid excessive power being placed in the hands of the monks.

Family

The 13th Dalai Lama was born in the village of Thakpo Langdun, one day by car, south-east from Lhasa,[3] and near Sam-ye Monastery, Tak-po province, in June, 1876[4] to parents Kunga Rinchen and Lobsang Dolma, a peasant couple.[5] Laird gives his birthdate as 27 May 1876,[3] and Mullin gives it as 'dawn on the 5th month of the Fire Mouse Year (1876).'[6]

Enthronement

In 1879, he was enthroned in the Grand Reception Hall at the Potala Palace.[7] The ceremony was approved by an imperial edict.[8] According to Qing historian Max Oidtmann, the Lhasa ambans were involved in the installation of the three-year-old incarnation on his dais. On the first day the young Dalai Lama was taken before the image of emperor Qianlong and performed the “three genuflections and nine prostrations” (a full kowtow) before it. On the next day, in the great Dug’eng Hall the emperor’s congratulatory edict was read out, and the Dalai Lama, together with the regent, again performed the ketou and bowed in the direction of the court.[9]

Contact with Agvan Dorzhiev

Agvan Dorzhiev, (1854–1938), a Khori-Buryat Mongol, and a Russian subject, was born in the village of Khara-Shibir, not far from Ulan Ude, to the east of Lake Baikal.[10] He left home in 1873 at 19 to study at the Gelugpa monastery, Drepung, near Lhasa, the largest monastery in Tibet. Having successfully completed the traditional course of religious studies, he began the academic Buddhist degree of Geshey Lharampa (the highest level of 'Doctorate of Buddhist Philosophy').[11] He continued his studies to become Tsanid-Hambo, or "Master of Buddhist Philosophy".[12] He became a tutor and "debating partner" of the teenage Dalai Lama, who became very friendly with him and later used him as an envoy to Russia and other countries.[13]

C.G.E. Mannerheim met Thubten Gyatso in Utaishan during the course of his expedition from Turkestan to Peking. Mannerheim wrote his diary and notes in Swedish to conceal the fact that his ethnographic and scientific party was also an elaborate intelligence gathering mission for the Russian army. The 13th Dalai Lama gave a blessing of white silk for the Russian Tsar and in return received Mannerheim's precious seven-shot officer's pistol with a full explanation of its use, as a gift.[14]

"Obviously," the 14th Dalai Lama said, "The 13th Dalai Lama had a keen desire to establish relations with Russia, and I also think he was a little skeptical toward England at first. Then there was Dorjiev. To the English he was a spy, but in reality he was a good scholar and a sincere Buddhist monk who had great devotion to the 13th Dalai Lama."[15]

Military expeditions in Tibet

After the British expedition to Tibet by Sir Francis Younghusband in early 1904, Dorzhiev convinced the Dalai Lama to flee to Urga in Mongolia, almost 2,400 km (1,500 mi) to the northeast of Lhasa, a journey which took four months. The Dalai Lama spent over a year in Urga and the Wang Khuree Monastery (to the west from the capital) giving teachings to the Mongolians. In Urga he met the 8th Bogd Gegeen Jebtsundamba Khutuktu several times (the spiritual leader of Outer Mongolia). The content of these meetings is unknown. According to report from A.D. Khitrovo, the Russian Border Commissioner in Kyakhta Town, the Dalai Lama and the influential Mongol Khutuktus, high lamas and princes "irrevocably decided to secede from China as an independent federal state, carrying out this operation under the patronage and support from Russia, taking care to avoid the bloodshed".[16] The Dalai Lama insisted that if Russia would not help, he would even ask Britain, his former foe, for assistance.

After the Dalai Lama fled, the Qing dynasty immediately proclaimed him deposed and again asserted sovereignty over Tibet, making claims over Nepal and Bhutan as well.[17] The Treaty of Lhasa was signed at the Potala between Great Britain and Tibet in the presence of the Amban and Nepalese and Bhutanese representatives on 7 September 1904.[18] The provisions of the 1904 treaty were confirmed in a 1906 treaty[19] signed between Great Britain and China. The British, for a fee from the Qing court, also agreed "not to annex Tibetan territory or to interfere in the administration of Tibet", while China engaged "not to permit any other foreign state to interfere with the territory or internal administration of Tibet".[19][20]

The Dalai Lama was suspected of involvement in the anti-foreign 1905 Tibetan Rebellion. The British invasion of Lhasa in 1904 had repercussions in the Tibetan Buddhist world,[21] causing extreme anti-western and anti-Christian sentiment among Tibetan Buddhists. The British invasion also triggered intense and sudden Qing intervention in Tibetan areas, to develop, assimilate, and bring the regions under strong Qing central control.[22] The Tibetan Lamas in Batang proceeded to revolt in 1905, massacring Chinese officials, French missionaries, and Christian Catholic converts. The Tibetan monks opposed the Catholics, razing the Catholic mission's Church, and slaughtering all Catholic missionaries and Qing officials.[23][24] The Manchu Qing official Fengquan was assassinated by the Tibetan Batang Lamas, along with other Manchu and Han Chinese Qing officials and the French Catholic priests, who were all massacred when the rebellion started in March 1905. Tibetan Gelugpa monks in Nyarong, Chamdo, and Litang also revolted and attacked missions and churches and slaughtered westerners.[25] The British invasion of Lhasa, the missionaries, and the Qing were linked in the eyes of the Tibetans, as hostile foreigners to be attacked.[26] Zhongtian (Chungtien) was the location of Batang monastery.[27] The Tibetans slaughtered the converts, torched the building of the missionaries in Batang due to their xenophobia.[28] Sir Francis Edward Younghusband wrote that At the same time, on the opposite side of Tibet they were still more actively aggressive, expelling the Roman Catholic missionaries from their long-established homes at Batang, massacring I many of their converts, and burning the mission-house.[29] There was anti Christian sentiment and xenophobia running rampant in Tibet.[30]

No. 10. Despatch from Consul-General Wilkinson to Sir E. Satow, dated Yünnan-fu, 28th April, 1905. (Received in London 14th June, 1905.) Pere Maire, the Provicaire of the Roman Catholic Mission here, called this morning to show me a telegram which he had just received from a native priest of his Mission at Tali. The telegram, which is in Latin, is dated Tali, the 24th April, and is to the effect that the lamas of Batang have killed PP. Musset and Soulie, together with, it is believed, 200 converts. The chapel at Atentse has been burnt down, and the lamas hold the road to Tachien-lu. Pere Bourdonnec (another member of the French Tibet Mission) begs that Pere Maire will take action. Pere Maire has accordingly written to M. Leduc, my French colleague, who will doubtless communicate with the Governor-General. The Provicaire is of opinion that the missionaries were attacked by orders of the ex-Dalai Lama, as the nearest Europeans on whom he could avenge his disgrace. He is good enough to say that he will give me any further information which he may receive. I am telegraphing to you the news of the massacre.

I have, &c., (Signed) W. H. WILKINSON. East India (Tibet): Papers Relating to Tibet [and Further Papers ...], Issues 2–4, Great Britain. Foreign Office, p. 12.[31][32]

Tibetans Christian families gunned down after refusing to give up their religion at Yanjing at the hands of the 13th Dalai Lama's messengers at the same time during the 1905 rebellion when Father Dubernard was beheaded and all the French missionaries were slaughtered by the Tibetan Buddhist Lamas.[33] The name "Field of Blood" was given to where the slaughter happened.[34][35]

In October 1906, John Weston Brooke was the first Englishman to gain an audience with the Dalai Lama, and subsequently he was granted permission to lead two expeditions into Tibet.[36] Also in 1906, Sir Charles Alfred Bell, was invited to visit Thubten Chökyi Nyima, the 9th Panchen Lama at Tashilhunpo, where they had friendly discussions on the political situation.[37]

The Dalai Lama later stayed at the great Kumbum Monastery near Xining and then travelled east to the most sacred of four Buddhist mountain in China, Wutai Shan located 300 km from Beijing. From here, the Dalai Lama received a parade of envoys: William Woodville Rockhill, the American Minister in Peking; Gustaf Mannerheim, a Russian army colonel (who later became the president of independent Finland); a German doctor from the Peking Legation; an English explorer named Christopher Irving; R.F. Johnson, a British diplomat from the Colonial Service; and Henri D’Ollone, the French army major and viscount.[38] The Dalai Lama was mounting a campaign to strengthen his international ties and free his kingdom from Chinese rule. Worried about his safety, Mannerheim even gave Tibet's spiritual pontiff a Browning revolver and showed him how to reload the weapon.[39]

In September 1908, the Dalai Lama was granted an audience with the Guangxu Emperor and Empress Dowager Cixi. The emperor tried to stress Tibet's subservient role, although the Dalai Lama refused to kowtow to him.[40] He stayed in Beijing until the end of 1908.[17]

When he returned to Tibet in December 1908, he began reorganising the government, but the Qing sent a military expedition of its own to Tibet in 1910 and he had to flee to India.[41][42]

In 1911 the Qing dynasty was overthrown in the Xinhai Revolution and by the end of 1912 the last Qing troops had been escorted out of Tibet.

Assumption of political power

In 1895, Thubten Gyatso assumed ruling power from the monasteries which had previously wielded great influence through the Regent. Due to his two periods of exile in 1904–1909, to escape the British invasion of 1904, and from 1910–1913 to escape a Chinese invasion, he became well aware of the complexities of international politics and was the first Dalai Lama to become aware of the importance of foreign relations. The Dalai Lama, "accompanied by six ministers and a small escort" which included his close aide, diplomat and military figure Tsarong Dzasa, fled via Jelep La[43] to Sikkim and Darjeeling, where they stayed almost two years. During this period he was invited to Calcutta by the Viceroy, Lord Minto, which helped restore relations with the British.[44]

Thubten Gyatso returned to Lhasa in January 1913 with Tsarong Dzasa from Darjeeling, where he had been living in exile. The new Chinese government apologised for the actions of the previous Qing dynasty and offered to restore the Dalai Lama to his former position. He replied that he was not interested in Chinese ranks and was assuming spiritual and political leadership of Tibet.[45]

After his return from exile in India in 1913, Thubten Gyatso assumed control of foreign relations and dealt directly with the Maharaja and the British Political officer in Sikkim and the king of Nepal rather than letting the Kashag or parliament do it.[46]

Thubten Gyatso declared independence from China in early 1913 (13 February), after returning from India following three years of exile. He then standardized the Tibetan flag in its present form.[47] At the end of 1912 the first postage stamps of Tibet and the first bank notes were issued.

Thubten Gyatso built a new medical college (Mentsikang) in 1913 on the site of the post-revolutionary traditional hospital near the Jokhang.[48]

Legislation was introduced to counter corruption among officials, a national taxation system was established and enforced, and a police force was created. The penal system was revised and made uniform throughout the country. "Capital punishment was completely abolished and corporal punishment was reduced. Living conditions in jails were also improved, and officials were designated to see that these conditions and rules were maintained."[49][50]

A secular education system was introduced in addition to the religious education system. Thubten Gyatso sent four promising students to England to study, and welcomed foreigners, including Japanese, British and Americans.[49]

As a result of his travels and contacts with foreign powers and their representatives (e.g., Pyotr Kozlov, Charles Alfred Bell and Gustaf Mannerheim), the Dalai Lama showed an interest in world affairs and introduced electricity, the telephone and the first motor cars to Tibet. Nonetheless, at the end of his life in 1933, he saw that Tibet was about to retreat from outside influences.

In 1930, Tibetan army invaded the Xikang and the Qinghai in the Sino-Tibetan War. In 1932, the Muslim Qinghai and Han-Chinese Sichuan armies of the National Revolutionary Army led by Chinese Muslim General Ma Bufang and Han General Liu Wenhui defeated the Tibetan army during the subsequent Qinghai–Tibet War. Ma Bufang overran the Tibetan armies and recaptured several counties in Xikang province. Shiqu, Dengke, and other counties were seized from the Tibetans.[51][52][53] The Tibetans were pushed back to the other side of the Jinsha river.[54][55] Ma and Liu warned Tibetan officials not to dare cross the Jinsha river again.[56] Ma Bufang defeated the Tibetans at Dan Chokorgon. Several Tibetan generals surrendered, and were demoted by the Dalai Lama.[57] By August, the Tibetans lost so much land to Liu Wenhui and Ma Bufang's forces that the Dalai Lama telegraphed the British government of India for assistance. British pressure led to Nanjing declaring a ceasefire.[58] Separate truces were signed by Ma and Liu with the Tibetans in 1933, ending the fighting.[59][60][61]

Prophesies and death

The 13th Dalai Lama predicted before dying:

"Very soon in this land (with a harmonious blend of religion and politics) deceptive acts may occur from without and within. At that time, if we do not dare to protect our territory, our spiritual personalities including the Victorious Father and Son (Dalai Lama and Panchen Lama) may be exterminated without trace, the property and authority of our Lakangs (residences of reincarnated lamas) and monks may be taken away. Moreover, our political system, developed by the Three Great Dharma Kings (Tri Songtsen Gampo, Tri Songdetsen and Tri Ralpachen) will vanish without anything remaining. The property of all people, high and low, will be seized and the people forced to become slaves. All living beings will have to endure endless days of suffering and will be stricken with fear. Such a time will come."[62]

Only 20 years later, the Chinese invasion of Tibet brought many of these prophesies to reality. During the Chinese Great Leap Forward between 200,000 and 1,000,000 Tibetans died. Approximately 6,000 monasteries were destroyed during the Cultural Revolution, destroying the vast majority of historic Tibetan architecture.

Footnotes

- Some text used with permission from www.simhas.org. The author of this text has requested that there appear a direct link to the website from which the information is taken.

References

- ↑ Sheel, R. N. Rahul. "The Institution of the Dalai Lama". The Tibet Journal, Dharamsala, India. Vol. XIV No. 3. Autumn 1989, p. 28. ISSN 0970-5368

- ↑ "His Holiness the Thirteenth Dalai Lama, Thupten Gyatso". Namgyal Monastery. Archived from the original on 21 October 2009. Retrieved 10 October 2009.

- 1 2 Laird 2007, p.211

- ↑ Bell (1946); p. 40-42

- ↑ http://www.dalailama.com/biography/the-dalai-lamas#13

- ↑ Mullin 1988, p.23

- ↑ The Thirteenth Dalai Lama, Thupten Gyatso, dalailama.com.

- ↑ Dorje Tseden, On the Thirteenth Dalai Lama Ngawang Lozang Thubten Gyatso (translated by Chen Guansheng), in China Tibetology Magazine, No 32004, 2005.

- ↑ Max Oidtmann, Playing the Lottery with Sincere Thoughts: the Manchus and the selection of incarnate lamas during the last days of the Qing, Academia.edu, p.31-32.

- ↑ Red Star Travel Guide.

- ↑ Chö-Yang: The Voice of Tibetan Religion and Culture. Year of Tibet Edition, p. 80. 1991. Gangchen Kyishong, Dharamsala, H.P., India.

- ↑ Ostrovskaya-Junior, Elena A. Buddhism in Saint Petersburg.

- ↑ French, Patrick. Younghusband: The Last Great Imperial Adventurer, p. 186. (1994). Reprint: Flamingo, London. ISBN 978-0-00-637601-9.

- ↑ Liukkonen, Petri. "Baron Carl Gustav (Emil) Mannerheim". Books and Writers (kirjasto.sci.fi). Finland: Kuusankoski Public Library. Archived from the original on 22 January 2010.

- ↑ Laird, Thomas (2006). The Story of Tibet: Conversations with the Dalai Lama, p. 221. Grove Press, N.Y. ISBN 978-0-8021-1827-1.

- ↑ Kuzmin, S.L. Hidden Tibet: History of Independence and Occupation. St. Pteresburg: Narthang, 2010, online version at http://savetibet.ru/2010/03/10/manjuria_2.html

- 1 2 Chapman, F. Spencer (1940). Lhasa: The Holy City, p. 137. Readers Union, London. OCLC 10266665

- ↑ Richardson, Hugh E.: Tibet & its History, Shambala, Boulder and London, 1984, p.268-270. The full English version of the convention is reproduced by Richardson.

- 1 2 "Convention Between Great Britain and China Respecting Tibet (1906)". Archived from the original on 11 August 2009. Retrieved 8 August 2009.

- ↑ Bell, Charles (1924) Tibet: Past and Present. Oxford: Clarendon Press; p. 288.

- ↑ Scottish Rock Garden Club (1935). George Forrest, V. M. H.: explorer and botanist, who by his discoveries and plants successfully introduced has greatly enriched our gardens. 1873–1932. Printed by Stoddart & Malcolm, ltd. p. 30. Retrieved 2014-06-28.

- ↑ Goldstein, Melvyn C. (1997). The Snow Lion and the Dragon: China, Tibet, and the Dalai Lama. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 26. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ↑ Tuttle, Gray (2005). Tibetan Buddhists in the Making of Modern China (illustrated, reprint ed.). Columbia University Press. p. 45. ISBN 0231134460. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ↑ Prazniak, Roxann (1999). Of Camel Kings and Other Things: Rural Rebels Against Modernity in Late Imperial China. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 147. ISBN 1461639638. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ↑ Lin, Hsiao-ting (December 2004). "When Christianity and Lamaism Met: The Changing Fortunes of Early Western Missionaries in Tibet". Pacific Rim Report. The Occasional Paper Series of the USF Center for the Pacific Rim. The University of San Francisco (36). Retrieved 13 July 2014.

- ↑ Bray, John (2011). "Sacred Words and Earthly Powers: Christian Missionary Engagement with Tibet". The Transactions of the Asiatic Society of Japan. fifth series. Tokyo: John Bray & The Asian Society of Japan (3): 93–118. Retrieved 13 July 2014.

- ↑ John Howard Jeffrey (1 January 1974). Khams or Eastern Tibet. Stockwell. pp. 66–67.

- ↑ Charles Bell (1992). Tibet Past and Present. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. pp. 60–. ISBN 978-81-208-1048-8.

- ↑ Sir Francis Edward Younghusband (1910). India and Tibet: A History of the Relations which Have Subsisted Between the Two Countries from the Time of Warren Hastings to 1910; with a Particular Account of the Mission to Lhasa of 1904. J. Murray. pp. 47–.

- ↑ Linda Willis (2010). Looking for Mr. Smith: Seeking the Truth Behind The Long Walk, the Greatest Survival Story Ever Told. Skyhorse Publishing Inc. pp. 164–. ISBN 978-1-61608-158-4.

- ↑ Great Britain. Foreign Office (1904). East India (Tibet): Papers Relating to Tibet [and Further Papers ...], Issues 2–4. Contributors India. Foreign and Political Dept, India. Governor-General. H.M. Stationery Office. p. 12. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ↑ East India (Tibet): Papers Relating to Tibet [and Further Papers ...]. H.M. Stationery Office. 1897. pp. 5–.

- ↑ Hattaway, Paul (2004). Peoples of the Buddhist World: A Christian Prayer Diary. William Carey Library. p. 129. ISBN 0878083618. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ↑ "Tibetan". SIM (Serving In Mission) – An International Christian Missions ...

- ↑ Hattaway, Paul (2000). Operation China. Piquant.

- ↑ Fergusson, W.N.; Brooke, John W. (1911). Adventure, Sport and Travel on the Tibetan Steppes, preface. Scribner, New York, OCLC 6977261

- ↑ Chapman (1940), p. 141.

- ↑ Tamm, Eric Enno. "The Horse That Leaps Through Clouds: A Tale of Espionage, the Silk Road and the Rise of Modern China." Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre, 2010, pp. 364. See http://horsethatleaps.com

- ↑ Tamm, Eric Enno. "The Horse That Leaps Through Clouds: A Tale of Espionage, the Silk Road and the Rise of Modern China." Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre, 2010, p. 368. See http://horsethatleaps.com

- ↑ Tamm, Eric Enno. "The Horse That Leaps Through Clouds: A Tale of Espionage, the Silk Road and the Rise of Modern China." Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre, 2010, pp. 367. See http://horsethatleaps.com

- ↑ Chapman (1940), p. 133.

- ↑ French, Patrick. Younghusband: The Last Great Imperial Adventurer, p. 258. (1994). Reprint: Flamingo, London. ISBN 978-0-00-637601-9.

- ↑ The Thirteenth Dalai Lama, Thupten Gyatso, dalailama.com

- ↑ Chapman (1940).

- ↑ Mayhew, Bradley and Michael Kohn. (2005). Tibet, p. 32. Lonely Planet Publications. ISBN 1-74059-523-8.

- ↑ Sheel, R. N. Rahul. "The Institution of the Dalai Lama". The Tibet Journal, Vol. XIV No. 3. Autumn 1989, pp. 24 and 29.

- ↑ Sheel, p. 20.

- ↑ Dowman, Keith. (1988). The Power-Places of Central Tibet: The Pilgrim's Guide, p. 49. Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd., London. ISBN 0-7102-1370-0.

- 1 2 Norbu, Thubten Jigme and Turnbull, Colin M. (1968). Tibet: An account of the history, the religion and the people of Tibet. Reprint: Touchstone Books. New York. ISBN 0-671-20559-5, pp. 317–318.

- ↑ Laird (2006), p. 244.

- ↑ Jiawei Wang; Nimajianzan (1997). The historical status of China's Tibet. 五洲传播出版社. p. 150. ISBN 7-80113-304-8. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ↑ Hanzhang Ya; Ya Hanzhang (1991). The biographies of the Dalai Lamas. Foreign Languages Press. p. 442. ISBN 0-8351-2266-2. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ↑ B. R. Deepak (2005). India & China, 1904–2004: a century of peace and conflict. Manak Publications. p. 82. ISBN 81-7827-112-5. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ↑ International Association for Tibetan Studies. Seminar, Lawrence Epstein (2002). Khams pa histories: visions of people, place and authority : PIATS 2000, Tibetan studies, proceedings of the 9th Seminar of the International Association for Tibetan Studies, Leiden 2000. BRILL. p. 66. ISBN 90-04-12423-3. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ↑ Gray Tuttle (2005). Tibetan Buddhists in the making of modern China. Columbia University Press. p. 172. ISBN 0-231-13446-0. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ↑ Xiaoyuan Liu (2004). Frontier passages: ethnopolitics and the rise of Chinese communism, 1921–1945. Stanford University Press. p. 89. ISBN 0-8047-4960-4. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ↑ K. Dhondup (1986). The water-bird and other years: a history of the Thirteenth Dalai Lama and after. Rangwang Publishers. p. 60. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ↑ Richardson, Hugh E. (1984). Tibet and its History. 2nd Edition, pp. 134–136. Shambhala Publications, Boston. ISBN 0-87773-376-7 (pbk).

- ↑ Oriental Society of Australia (2000). The Journal of the Oriental Society of Australia, Volumes 31–34. Oriental Society of Australia. pp. 35, 37. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ↑ Michael Gervers; Wayne Schlepp (1998). Historical themes and current change in Central and Inner Asia: papers presented at the Central and Inner Asian Seminar, University of Toronto, April 25–26, 1997, Volume 1997. Joint Centre for Asia Pacific Studies. Joint Centre for Asia Pacific Studies. p. 195. ISBN 1-895296-34-X. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ↑ Wars and Conflicts Between Tibet and China

- ↑ Rinpoche, Arjia (2010). Surviving the Dragon: A Tibetan Lama's Account of 40 Years under Chinese Rule. Rodale. p. vii. ISBN 9781605291628.

Further reading

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Bell, Charles (1946) Portrait of a Dalai Lama: the Life and Times of the Great Thirteenth by Charles Alfred Bell, Sir Charles Bell, Publisher: Wisdom Publications (MA), January 1987, ISBN 978-0-86171-055-3 (first published as Portrait of the Dalai Lama: London: Collins, 1946).

- Bell, Charles (1924) Tibet: Past and Present. Oxford: Clarendon Press

- Bell, Charles (1931) The Religion of Tibet. Oxford: Clarendon Press

- Gelek, Surkhang Wangchen. 1982. "Tibet: The Critical Years (Part 1) The Thirteenth Dalai Lama". The Tibet Journal. Vol. VII, No. 4. Winter 1982, pp. 11–19.

- Goldstein, Melvyn C. A History of Modern Tibet, 1913–1951: the demise of the Lamaist state (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1989) ISBN 978-0-520-07590-0

- Laird, Thomas (2007). The Story of Tibet : Conversations with the Dalai Lama (paperback ed.). London: Atlantic. ISBN 978-1-84354-145-5.

- Mullin, Glenn H (1988). The Thirteenth Dalai Lama: Path of the Bodhisattva Warrior (paperback ed.). Ithaca, New York: Snow Lion. ISBN 0-937938-55-6.

- Mullin, Glenn H. (2001). The Fourteen Dalai Lamas: A Sacred Legacy of Reincarnation, pp. 376–451. Clear Light Publishers. Santa Fe, New Mexico. ISBN 1-57416-092-3.

- Richardson, Hugh E.(1984): Tibet & its History. Boulder and London: Shambala. ISBN 0-87773-292-2.

- Samten, Jampa. (2010). "Notes on the Thirteenth Dalai Lama's Confidential Letter to the Tsar of Russia." In: The Tibet Journal, Special issue. Autumn 2009 vol XXXIV n. 3-Summer 2010 vol XXXV n. 2. "The Earth Ox Papers", edited by Roberto Vitali, pp. 357–370.

- Smith, Warren (1997):Tibetan Nation. New Delhi: HarperCollins. ISBN 0-8133-3155-2

- Tamm, Eric Enno. "The Horse That Leaps Through Clouds: A Tale of Espionage, the Silk Road and the Rise of Modern China." Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre, 2010, Chapter 17 & 18. ISBN 978-1-55365-269-4. See http://horsethatleaps.com

- Tsering Shakya (1999): The Dragon in the Land of Snows. A History of Modern Tibet since 1947. London:Pimlico. ISBN 0-7126-6533-1

- The Wonderful Rosary of Jewels. An official biography compiled for the Tibetan Government, completed in February 1940

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Thubten Gyatso, 13th Dalai Lama. |

- The Thirteenth Dalai Lama, Tubten Gyatso by Tsering Shakya

| Buddhist titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Trinley Gyatso |

Dalai Lama 1879–1933 Recognized in 1878 |

Succeeded by Tenzin Gyatso |