Threonine

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Threonine | |

| Other names

2-Amino-3-hydroxybutanoic acid | |

| Identifiers | |

| 3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChemSpider | |

| DrugBank | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.704 |

| EC Number | 201-300-6 |

| PubChem CID |

|

| UNII | |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C4H9NO3 | |

| Molar mass | 119.12 g·mol−1 |

| (H2O, g/dl) 10.6(30°),14.1(52°),19.0(61°) | |

| Acidity (pKa) | 2.63 (carboxyl), 10.43 (amino)[1] |

| Supplementary data page | |

| Refractive index (n), Dielectric constant (εr), etc. | |

| Thermodynamic data |

Phase behaviour solid–liquid–gas |

| UV, IR, NMR, MS | |

| Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| | |

| Infobox references | |

Threonine (abbreviated as Thr or T) encoded by the codons ACU, ACC, ACA, and ACG is an α-amino acid that is used in the biosynthesis of proteins. It contains an α-amino group (which is in the protonated −NH+

3 form under biological conditions), an α-carboxylic acid group (which is in the deprotonated −COO− form under biological conditions), and an alcohol containing side chain, classifying it as a polar, uncharged (at physiological pH) amino acid. It is essential in humans, meaning the body cannot synthesize it, and must be ingested in our diet. Threonine is synthesized from aspartate in bacteria such as E. coli.[2]

Threonine sidechains are often hydrogen bonded; the most common small motifs formed are ST turns, ST motifs (often at the beginning of alpha helices) and ST staples (usually at the middle of alpha helices).

Stereoisomerism

The threonine residue is susceptible to numerous posttranslational modifications. The hydroxyl side-chain can undergo O-linked glycosylation. In addition, threonine residues undergo phosphorylation through the action of a threonine kinase. In its phosphorylated form, it can be referred to as phosphothreonine.

It is a precursor of glycine, and can be used as a prodrug to reliably elevate brain glycine levels.

History

Threonine was discovered as the last of the 20 common proteinogenic amino acids in 1935s by William Cumming Rose, collaborating with Curtis Meyer and William Rose. The amino acid was named threonine because it was similar in structure to threose, a four-carbon monosaccharide or carbohydrate with molecular formula C4H8O4[3]

|

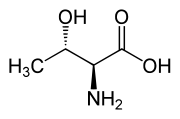

| L-Threonine (2S,3R) and D-Threonine (2R,3S) |

|

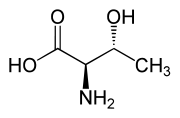

| L-allo-Threonine (2S,3S) and D-allo-Threonine (2R,3R) |

Threonine is one of two proteinogenic amino acids with two chiral centers, the other being isoleucine. Threonine can exist in four possible stereoisomers with the following configurations: (2S,3R), (2R,3S), (2S,3S) and (2R,3R). However, the name L-threonine is used for one single diastereomer, (2S,3R)-2-amino-3-hydroxybutanoic acid. The second stereoisomer (2S,3S), which is rarely present in nature, is called L-allo-threonine. The two stereoisomers (2R,3S)- and (2R,3R)-2-amino-3-hydroxybutanoic acid are only of minor importance.

Biosynthesis

As an essential amino acid, threonine is not synthesized in humans, hence we must ingest threonine in the form of threonine-containing proteins. In plants and microorganisms, threonine is synthesized from aspartic acid via α-aspartyl-semialdehyde and homoserine. Homoserine undergoes O-phosphorylation; this phosphate ester undergoes hydrolysis concomitant with relocation of the OH group.[4] Enzymes involved in a typical biosynthesis of threonine include:

- aspartokinase

- β-aspartate semialdehyde dehydrogenase

- homoserine dehydrogenase

- homoserine kinase

- threonine synthase.

Metabolism

Threonine is metabolized in two ways:

- It is converted to pyruvate via threonine dehydrogenase. An intermediate in this pathway can undergo thiolysis with CoA to produce acetyl-CoA and glycine.

- In humans, it is converted to α-ketobutyrate. (The gene for threonine dehydrogenase is a pseudogene in humans). This is the primary pathway for threonine degradation. The mechanism of the first step is analogous to that catalyzed by serine dehydratase, and the serine and threonine dehydratase may actually be the same enzyme.

Requirements

The Food and Nutrition Board (FNB) of the U.S. Institute of Medicine set Recommended Dietary Allowances (RDAs) for essential amino acids in 2002. For threonine, for adults 19 years and older, 20 mg/kg body weight/day.[5]

Sources

Foods high in threonine include cottage cheese, poultry, fish, meat, lentils, Black turtle bean[6] and Sesame seeds.[7]

Racemic threonine can be prepared from crotonic acid by alpha-functionalization using mercury(II) acetate.[8]

References

- ↑ Dawson, R.M.C., et al., Data for Biochemical Research, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1959.

- ↑ Raïs, Badr; Chassagnole, Christophe; Lettelier, Thierry; Fell, David; Mazat, Jean-Pierre (2001). "Threonine synthesis from aspartate in Escherichia coli cell-free extracts: pathway dynamics" (PDF). J Biochem. 356: 425–32. PMC 1221853

. PMID 11368769.

. PMID 11368769. - ↑ Meyer, Curtis (20 July 1936). "The Spatial Configuation of Alpha-Amino-Beta-Hydroxy-n-Butyric Acid" (PDF). Journal of Biological Chemistry. 115 (3).

- ↑ Lehninger, Albert L.; Nelson, David L.; Cox, Michael M. (2000). Principles of Biochemistry (3rd ed.). New York: W. H. Freeman. ISBN 1-57259-153-6..

- ↑ Institute of Medicine (2002). "Protein and Amino Acids". Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrates, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein, and Amino Acids. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. pp. 589–768.

- ↑ http://ndb.nal.usda.gov/ndb/foods/show/4632?fg=&man=&lfacet=&count=&max=&sort=&qlookup=&offset=&format=Full&new=

- ↑ http://nutritiondata.self.com/

- ↑ Carter, Herbert E.; West, Harold D. (1940). "dl-Threonine". Org. Synth. 20: 101.; Coll. Vol., 3, p. 813.